Francisco Goya: “Self-Portrait” (1815)

Goya is almost 70 here, long deaf, with several lifetimes behind him, a career at court, political upheavals, illness, and numerous portraits, engravings, and phantasmagorical paintings. In this self-portrait, we see disheveled hair, a tired but not very old face. Goya is again receiving royal commissions, but in a few years, he will leave Spain for France forever.

- Francisco Goya: “Self-Portrait” (1815)

- Karl Bryullov: “Self-Portrait” (1833)

- Gustave Courbet: “The Desperate Man” (1843–1845)

- Edgar Degas: “Degas Saluting” (1865–1866)

- Vincent Van Gogh: “Self-Portrait” (1889)

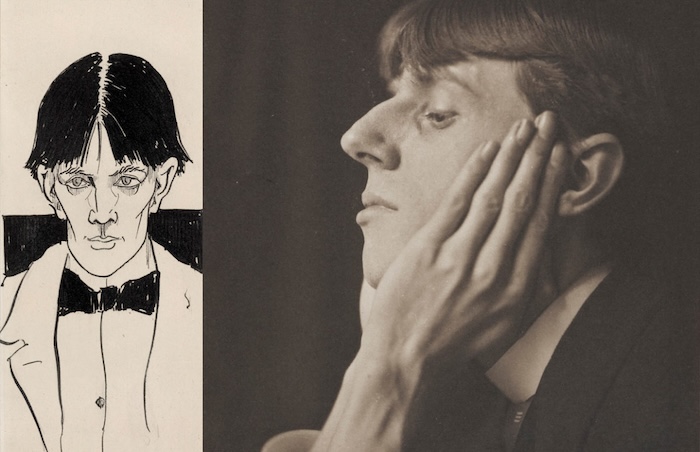

- Aubrey Beardsley: “Self-Portrait” (1892)

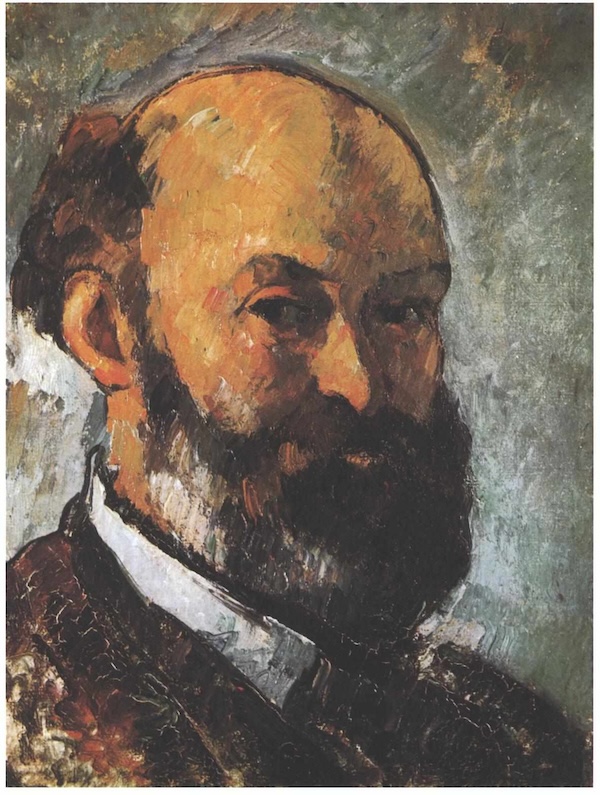

- Paul Cézanne: “Self-Portrait” (1882–1885)

- Mikhail Vrubel: “Self-Portrait” (1885)

- Edvard Munch: “Self-Portrait with Burning Cigarette” (1895)

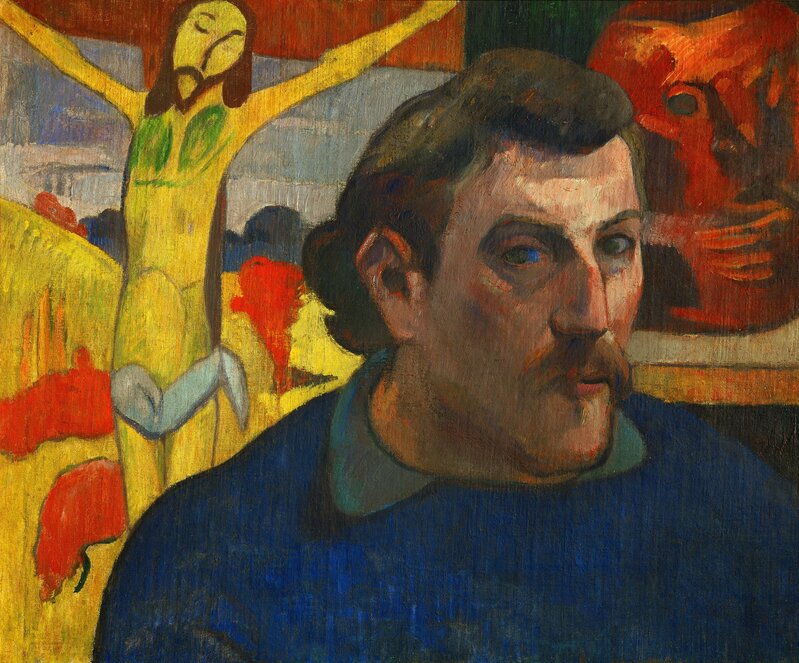

- Paul Gauguin: “Self-Portrait with Yellow Christ” (1890–1891)

Goya is an amazing person, changing simultaneously with the era and yet always recognizable, unique in his mature works. It is his engravings and drawings that will later fascinate the surrealists, it is he who was not afraid to bring out the fears and subconscious images that psychoanalysts would later deal with. But there are no monsters in the portrait — only a man with slumped shoulders and a heavy gaze who has endured a great deal.

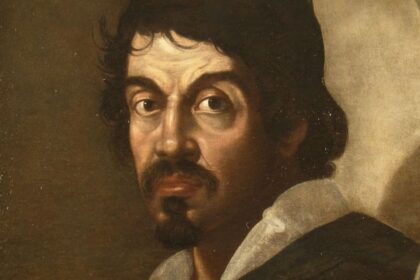

Karl Bryullov: “Self-Portrait” (1833)

In 1833, Karl Bryullov was on his way to European fame. He had just finished the blockbuster painting “The Last Day of Pompeii,” which impressed viewers in Milan and Rome, and later in St. Petersburg. This portrait depicts a very self-satisfied young man. Contemporaries compared him to Apollo – alas, poor health and a questionable lifestyle soon left nothing of this beauty. Fashionable curls, a dark jacket – the set of a romantic, but not a lonely wanderer, rather a winner who knows his worth. Well-groomed, pampered by Italy, calm and with a touch of gloss. A tribute to romantic fashion is mandatory: furrowed brows, attentive gaze, mouth slightly open, collar unbuttoned. He is ready for a quick remark or listening attentively to the interlocutor. This is a man in his prime, full of life, like the heroes of Baroque sculpture, which he, of course, saw in his beloved Rome.

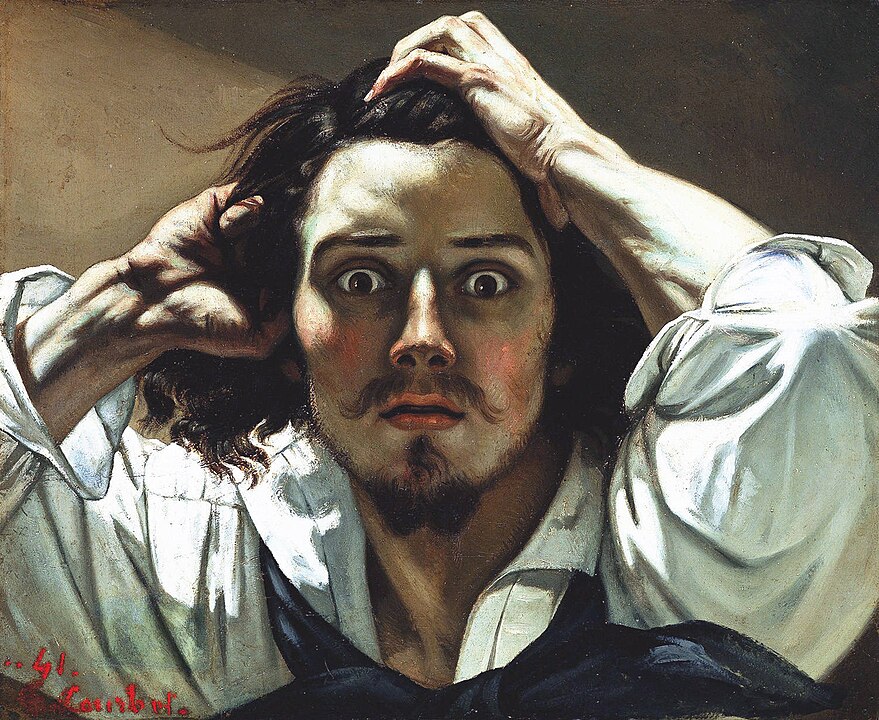

Gustave Courbet: “The Desperate Man” (1843–1845)

There is no doubt that Courbet would have started an Instagram account these days and photographed himself with a dog and in unusual poses. He loved to play and admire himself. And his early self-portraits unequivocally point to this. One of Courbet’s many roles (wounded, musician, hedonist with a pipe, etc.) is a man on the verge of despair. Was he ever in despair? Undoubtedly. Did he look in the mirror at these moments, wringing his hands and grabbing his thick hair? Unlikely.

In the self-portrait, we see an acting study: he seems to be playing a dramatic role in front of the camera. And he’s overacting a bit — which is quite in the tradition of 17th-18th century artists. At that time, many studies of facial expressions and gestures were painted, where models exaggeratedly demonstrate emotions. Courbet is the most accessible model for himself and at the same time an aesthetic object. Quite modern narcissism, quite understandable interest. The future “chief realist,” the subverter of the ideal in painting, is still practicing on himself and doing it with pleasure.

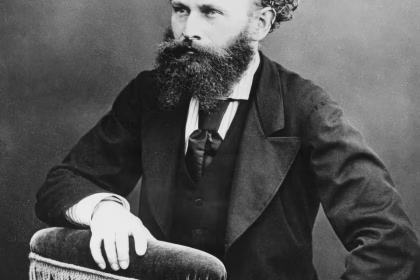

Edgar Degas: “Degas Saluting” (1865–1866)

The self-doubting melancholic and misanthrope Degas often depicted himself – but not for self-admiration, rather for research. He always has a sad-skeptical look and not too sociable appearance. It’s all the more strange that he greets us. Why? Probably, the ironic Degas repeats a popular pose from photographic visiting cards, on which gentlemen often raised their hats, greeting the addressee. At this time, Degas was already interested in photography and later briefly became an amateur photographer himself. And this time was pivotal for him: it was then that he moved away from academic contrived subjects and turned to modern life. Already in the next decade, Degas will exhibit in the company of the Impressionists and look like an innovator. For now, he is on the way.

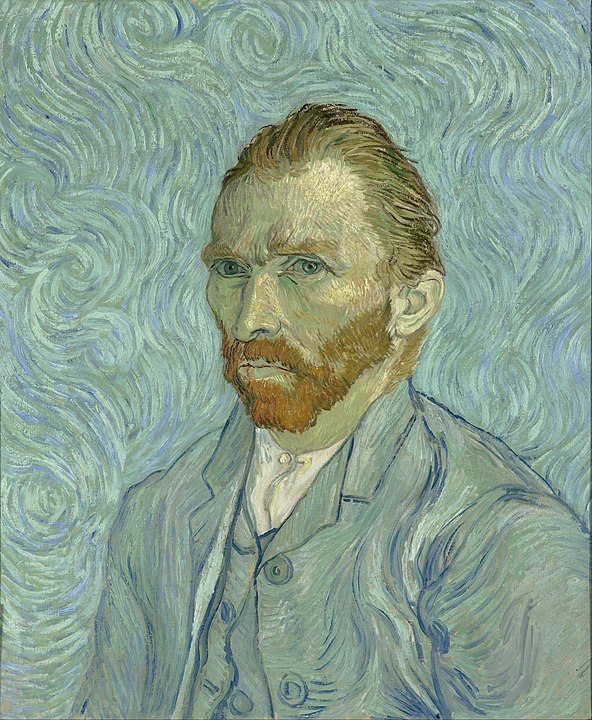

Vincent Van Gogh: “Self-Portrait” (1889)

Van Gogh paints his face as if slowly and tensely crawling up a rock: not a single easy line, everything is excessive. In all his self-portraits, we see a dramatic experience of forms, surfaces, and color. This self-portrait — one of the last three — was painted in September 1889, 10 months before his death. At this time, Van Gogh was confined to the Saint-Rémy asylum. It was here that he painted the famous “Starry Night” – an unreal, cosmic landscape.

This portrait is also a kind of landscape — rocky, craggy, southern. There’s no straw hat, no beard, no pipe — everything is austere and bare. The face is turned so that the mutilated ear is not visible. The eyes are like voids, the nose like a mountain ridge. It seems that there is nothing to cling to in this face: it’s like a mountain against a blue sky. Van Gogh seems to become nature itself, and nature in the process of development and change. Looking into himself, the artist sees forces of a different, non-human scale.

Aubrey Beardsley: “Self-Portrait” (1892)

Dressed for a social reception (jacket, vest, bow tie), the 20-year-old Beardsley seems to be looking into a narrow mirror. He has a sickly thin decadent face, a frozen gaze, sharp cheekbones. The ears and nostrils are emphasized as if he’s listening and sniffing. Beardsley was able to make a sarcastic remark in response to critical attacks — this is reminded by the skeptical smirk. All lines are elongated, the figure with black hair resembles a gloomy night flower.

Where does such a young person get such acuteness of feelings, sickness, melancholy? Beardsley was forced to grow up early: he had been suffering from tuberculosis since he was seven. And he also became famous early, by the mid-1890s: society treated him with rejection, and the press aggressively met his works. In 1892, scandalous fame had not yet come to him, but he already looks tired and reminds one of Dorian Gray: outwardly young, inwardly an old man. Beardsley already guesses that in a few years the disease will defeat him. And the world of his famous refined-sickly drawings — artificial, fantastical — probably distracted from suffering, human stupidity, and earthly troubles.

Paul Cézanne: “Self-Portrait” (1882–1885)

Who is infinitely far from selfies as a narcissistic action, it’s Cézanne. In fact, he doesn’t care what to paint: an apple, his wife, a coffee pot, or himself. As long as the object doesn’t move. After all, Cézanne is concerned with unchanging eternal things. He molds the world anew – like a sculptor, from colorful matter. The shadows are colored, the objects are voluminous and heavy. There’s no sensuality (this is the opposite of Bryullov), no conveyance of textures. There is strength, power, clumsiness, the slowness of an analyst. As if he wants to understand the essence of objects. Cézanne painted his pictures, including self-portraits, for a long time, as if summarizing impressions from individual moments.

The artist’s task here is not to grasp the surface of the phenomenon, but to study it carefully. And you need to look at the self-portrait for a long time, like an old tree with annual rings. This is already a mature artist who has found his manner of building form. His landscapes and still lifes are self-sufficient, and he doesn’t want to please anyone. It’s impossible to guess if he has feelings and mood: he’s not looking at us and doesn’t live in the portrait for us. He is on his own. Like a mountain or an apple.

Mikhail Vrubel: “Self-Portrait” (1885)

A demonic bird-like face, dramatic light – is this an acting role or a nightmare? In many self-portraits, Vrubel peers into his face, as if trying to understand the degree of its materiality. It was during the period of creating this drawing (when he was healing his heartache in Odessa) that Vrubel finds an image that will later completely absorb him — the image of the Demon. This self-portrait brings to mind Gogol with his grotesque, night scenes, and mysticism: we see the contrast of light and darkness, a grotesque nose, vagueness of outlines.

The hatching is very bold, even rough, in some places the edges sculpt the form, and in some places one has to guess what exactly is depicted. The mouth is almost invisible, the eyes look questioningly. There is no clarity, no certainty, but there is a question, uncertainty. For Vrubel, there is a very thin line between the real and unreal worlds — and this is probably related to his future madness. And in this self-portrait, the young strange artist depicts himself not as a whole personality, but as a vision that flashed in the darkness.

Edvard Munch: “Self-Portrait with Burning Cigarette” (1895)

Munch would make an ideal character for a dark TV series. His life is excessively dramatic: handsome appearance, romantic passions, strange ideas, paranoia, outbursts of irritation, the death of loved ones, illnesses, anxieties, and fears. In his 1895 self-portrait, he reminds us of his bohemian nature: standing and smoking a cigarette as if in the spotlight. This brings to mind the artistic Berlin café “The Black Piglet,” where poets, writers, and artists would meet, as well as another self-portrait painted in 1903, where the artist depicts himself in hellish flames.

Darkness and flashes of light, twilight and radiance—something tumultuous, contrasting, like the music of Wagner or Sibelius. By this time, he had already begun the “Frieze of Life” series, which includes the famous “The Scream.” All of Munch’s paintings are deeply personal and autobiographical: there is always a sense of drama, suffering, fear, jealousy, and pain. This is a self-portrait of an anxious man at the turn of the century: there is no harmony in him, the future terrifies him, he is in despair and stupor.

Paul Gauguin: “Self-Portrait with Yellow Christ” (1890–1891)

This strongman with a mysterious expression constantly encrypted his paintings. Gauguin’s self-portrait is a symbolic manifesto in which he sums up his life. Here is the Breton period, when he painted “The Yellow Christ” surrounded by worshippers (whether it’s a mystical vision of Golgotha or the veneration of a statue of Christ in Brittany). And here is the Tahitian period, when he made a grotesque ceramic vessel in the shape of his own head, associating himself with something like an ancient totem. This vessel is visible in the background—so are we looking at two self-portraits? Or even three (since Gauguin considered the work of an artist to be something like the Stations of the Cross)? On the left is his past: an interest in the Middle Ages with a touch of Japanese influence, icons, and sculptures of Brittany, ancient customs. On the right, behind his mighty shoulder, is the present: he has become a primitive ceramic vessel, as if made by islanders. Here is Christianity and paganism, and here is the new prophet—Gauguin. He is a myth-maker, a demiurge, a mystifier, almost a shaman, and many other artists will follow his path into the 20th century.