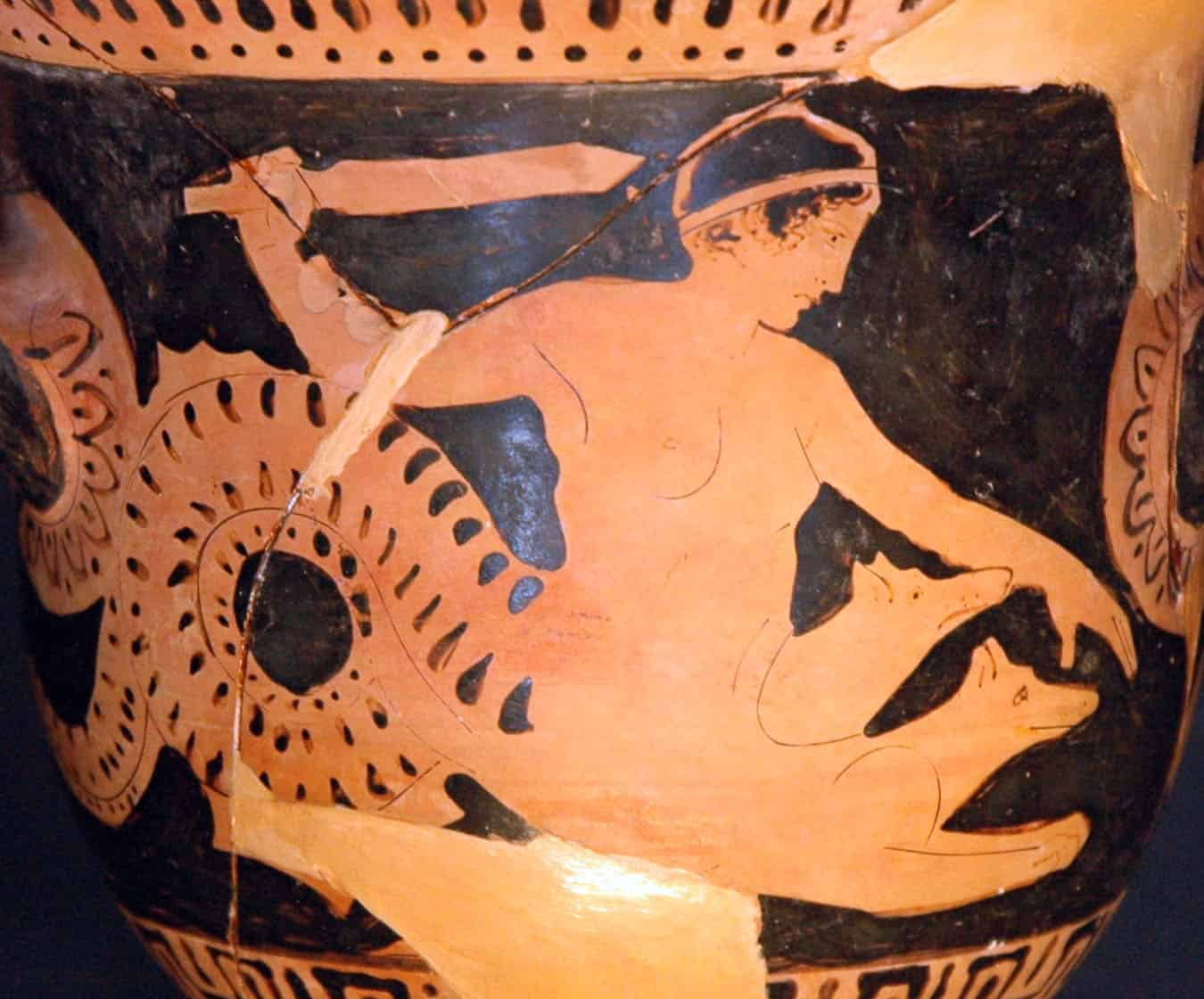

Charybdis (in ancient Greek Χάρυϐδις / Khárubdis, pron.: [kaʀibd] “karybde”) and Scylla are two sea monsters from Greek mythology, located on either side of a strait traditionally identified as the Strait of Messina. The legend is the origin of the expression “between Scylla and Charybdis,” which means “to go from bad to worse.” Charybdis in ancient Greek epic poetry is the personification of the all-devouring sea whirlpool (etymologically, Charybdis derives from the word meaning “whirlpool”). In the Odyssey, Charybdis is depicted as a sea deity (Ancient Greek: δία Χάρυβδις), dwelling in the strait beneath a rock within an arrow’s flight from another rock, which served as Scylla’s lair.

Greek mythology

Charybdis was the daughter of Poseidon and Gaia. She was perpetually hungry. When she devoured the cattle of Heracles, the son of Zeus, he punished her by sending her to the bottom of a strait “formed by a sea arm that separates Rhegium from Messene.”

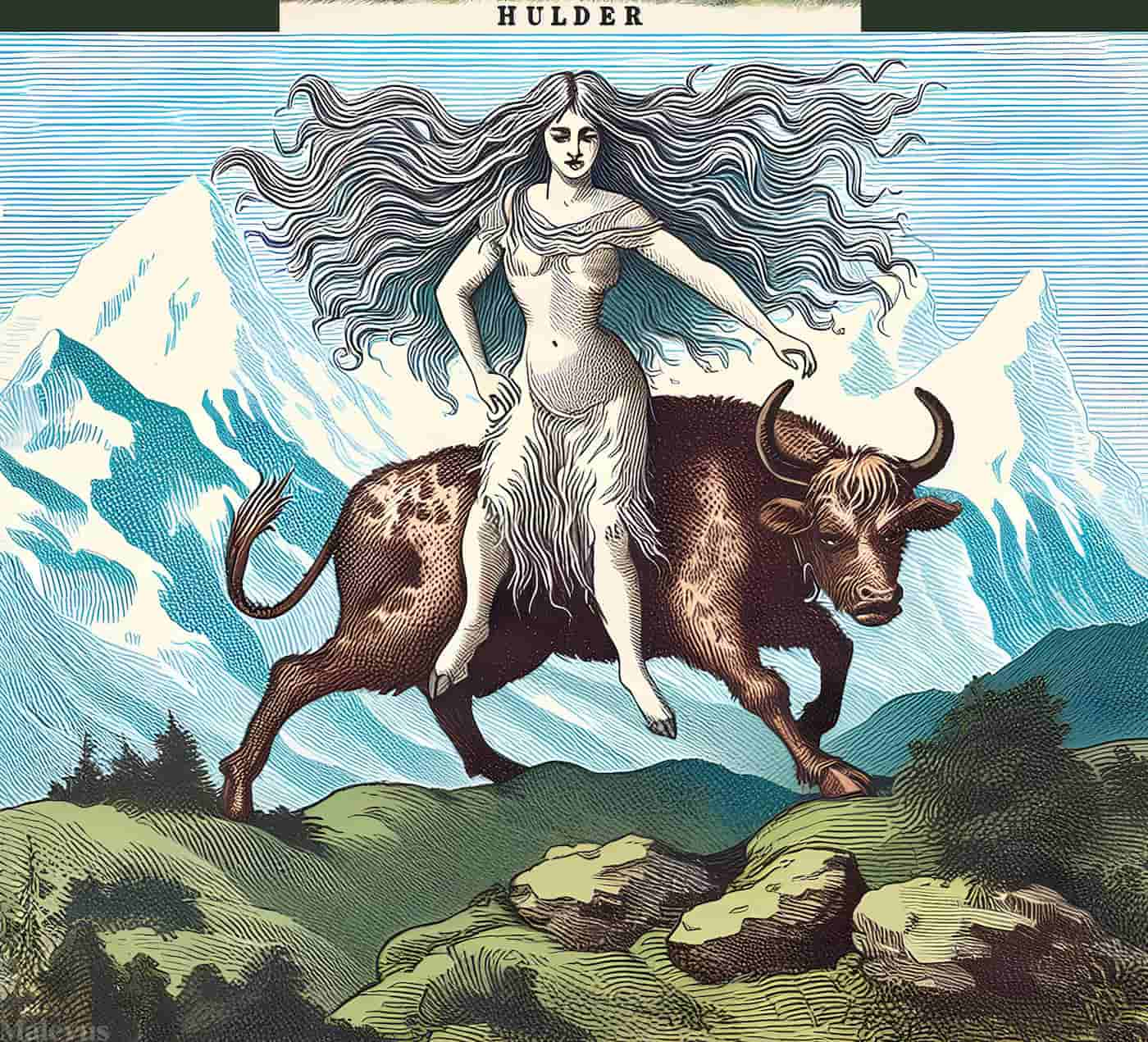

Not far away lived Scylla. Originally, she was a nymph whom Glaucus was madly in love with. As this love was not reciprocated, Glaucus went to the sorceress Circe for a love potion, but she, deeply in love with Glaucus and jealous of Scylla, took the opportunity to transform the nymph into a terrifying monster.

In the Odyssey, Circe describes to Odysseus the route he must follow in these terms: “The route leads you between the Two Rocks. One thrusts its pointed peak up to the vast sky; a dark blue cloud surrounds it. No mortal could climb or stand there, […] for the rock is smooth and seems polished all around. In the middle of this rock, there is a dark cave facing northwest towards Erebus. Straight toward it, you shall steer your hollow ship, O noble Odysseus! With an arrow, a strong man drawing from a hollow ship could not touch the bottom of this cave. Scylla, with her resounding cry, resides there.”

Scylla is portrayed as a monstrous creature whose resounding cry is a bark echoing on the cave walls; Circe describes her as “eternal evil, a terrible scourge, a wild reality that cannot be fought.” Despite Circe’s recommendations, Odysseus equips himself with two long spears to confront the monster, but in vain; he loses six of his sailors and orders them to quickly steer away from the rock. As for Charybdis, “it swallows the black water; three times a day it spits it out; three times it swallows it again.” This whirlpool is so powerful that even Poseidon himself would be unable to save anyone caught in its vortex.

Interpretations

Since Homer, Charybdis and Scylla have been two associated terms, both opposed and complementary. Scylla is a high fixed rock that rises to the sky; Charybdis lies in the depths of the sea, like a liquid mass descending and rising in spiral movements. These two dangers that threatened sailors were identified since antiquity by Thucydides as “the formidable passage, given its narrowness and currents,” which we now call the Strait of Messina. This whirlpool and reef are indicated on our sea charts and defined by Nautical Instructions: “The meeting of two opposing currents produces, in various places in the strait, whirlpools and large swirls called garofali. The main garofali are on the coast of Sicily, between Cape Faro and Punta Sottile, with the ebb tide, and in front of the tower of Palazzo, with the flood tide; this latter garofalo is very strong: it is the Charybdis of the Ancients.”

Following Circe’s instructions, Odysseus bypassed the sirens, whom experienced navigators recognize as the Galli, and headed for Scylla, a rock that appears on the port side before the narrow gate giving access to the south. It is also indicated in our modern Nautical Instructions: “The city of Scilla is built in an amphitheater on the steep cliffs of a prominent point to the north.” On this high and rocky promontory, the Greeks imagined the monster Scylla in its lair. Midway up, there is indeed a cave and the cliff resounds with the blows dealt by the surging waves.

Also noteworthy are the numerous philosophical interpretations, sometimes alchemical, both pagan and Christian, that Scylla and Charybdis have been the subject of since antiquity, notably by Heraclides Ponticus, Eustathius, and Christopher Contoleon.

In the twentieth century, the philosopher Emmanuel d’Hooghvorst also commented on them in this sense: “In Greek oneiromancy, teeth signify bones. In each of its mouths, this monster [Scylla] has three rows of teeth; it is the triple series of human vertebrae, two of which are mobile and one fixed. ‘In these nineteen mobile vertebrae, I spend my life in the vanity of this century. Such is the danger, such is the trap of souls.'”

Doxography

In the earliest mythological accounts, Charybdis hardly played any role; later she was named the daughter of Poseidon and Gaia.

In various mythographic sources, Scylla is considered:

- the daughter of Phorcys and Hecate;

- or the daughter of Phorbas and Hecate;

- the daughter of Triton and Lamia (according to Stesichorus, daughter of Lamia);

- the daughter of Typhon and Echidna;

- the daughter of Poseidon (Deima) and Crataeis;

- the daughter of Triton;

- or the daughter of Poseidon or Gaia.

- the daughter of the river Crataeis and Trienus (or Phorcus); Homer calls her the mother nymph Crataeis, daughter of Hecate and Triton.

- According to Acusilaus and Apollonius, the daughter of Phorcus and Hecate, named Crataeis;

- According to another version, the daughter of Tyrrhenus;

- In Vergil’s works, the monster Scylla is identified with the daughter of Nisus.

In some tales, Scylla is sometimes portrayed as a beautiful maiden: Glaukos sought her love, but the sorceress Circe herself fell in love with Glaukos. Scylla used to bathe, and Circe, out of jealousy, poisoned the water with potions, turning Scylla into a fierce beast. Her beautiful body was disfigured, with its lower part turning into a row of dog heads.

According to another tale, this transformation was performed by Amphitrite, who, upon learning that Scylla had become Poseidon’s beloved, decided to get rid of the dangerous rival by this means (poisoning the water).

According to the “Epic Cycle” by Dionysius of Samos, for the abduction of one of the cattle of Geryon, Scylla was killed by him but was revived again by her father Phorcys, who burned her body.

Description by Homer

The rock of Scylla rose high with a sharp peak to the sky and was perpetually covered with dark clouds and twilight; access to it was impossible due to its smooth surface and steepness. In the middle of it, at a height unreachable even for an arrow, there was a cave with a dark entrance facing west. In this cave dwelled the fearsome Scylla. Without ceasing to bark (Σκύλλα”barking”), the monster echoed the surroundings with piercing cries. In front of Scylla, there were twelve legs moving, six long flexible necks rising from shaggy shoulders, and on each neck there was a head protruding; in her mouth, there were frequent, sharp teeth arranged in three rows. By backing her hindquarters into the depths of the cave and sticking out her chest, she hunted prey with all her heads, groping around the rock with her paws and catching dolphins, seals, and other sea creatures. When a ship passed by the cave, Scylla, opening all her mouths wide, would snatch six men from the ship at once. This is how Homer outlines Scylla.

Charybdis, on the other hand, lacks individuality in Homer’s description: it is simply a sea whirlpool, agitated by an unseen water goddess, which three times a day swallows and as many times spews out seawater beneath the second of the mentioned rocks.

When Odysseus with his companions passed through the narrow strait between Scylla and Charybdis, the latter eagerly swallowed the salty water. Calculating that death from Charybdis threatened inevitably to all, whereas Scylla could snatch only six men with her paws, Odysseus, losing six of his comrades, who were devoured by Scylla, avoids the dreadful strait.

Later, as punishment for sacrilegiously striking the cattle of Hyperion, Zeus ordered a storm that wrecked Odysseus’ ship and scattered his companions’ bodies in the sea. Odysseus himself, having managed to cling to the mast and keel, was again carried by the wind towards Charybdis. Seeing the inevitable death, at the moment when the wreckage of the ship fell into the whirlpool, he grabbed the branches of a fig tree, which descended to the water, and hung in that position until Charybdis threw back the “desired logs.” Then he, spreading his arms and legs, fell with all his weight on the thrown remnants of the ship and, straddling them, escaped from the whirlpool.

According to Gaius Julius Hyginus, below she is a dog, and above she is a woman. She had six dogs born to her, and she devoured six of Odysseus’ companions.

Like Odysseus, Jason and his companions safely passed by Charybdis, thanks to the help of Thetis; Aeneas, who also had to pass between Scylla and Charybdis, preferred to circumvent the dangerous place.

In Vergil’s works, there are several Scyllas, who, among other monsters, inhabit the vestibule of Tartarus.

Geography

Geographically, the whereabouts of Scylla and Charybdis were associated by the ancients with the Strait of Messina between Sicily and Calabria, with Charybdis being located in the Sicilian part of the strait under Cape Pelorus, and Scylla on the opposite cape (in Bruttium, near Rhegium), which bore her name in historical times (Latin Scyllaeum promontorium, Ancient Greek: Σκύλλαιον). It is noteworthy that the fantastic description of the mythical dangerous strait by Homer does not match the actual nature of the Strait of Messina, which is not so dangerous for sailors. It is known that parts of the rocks collapsed during the strongest earthquake on February 5, 1783, in this region. In reality, Scylla is a sharp-pointed rock, and Charybdis is a large whirlpool.

In addition to the Messina Charybdis, in antiquity, under the name Charybdis, there was a chasm where the flow of the river Orontes disappeared for a certain distance in Syria, between Antioch and Apamea, and a whirlpool near Gades in Spain.

Evocations

Antiquity

- In the story of the Argonauts, they cross the strait without difficulty thanks to divine interventions, going from Sardinia to the Ionian Sea, on their return from Colchis.

- In the Odyssey, Odysseus is called to cross the strait with his ship, then is confronted with Charybdis a second time after a shipwreck.

- In Virgil’s Aeneid, the hero must cross the strait on his way to Latium.

In Culture

Literature

- 1831: in Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris, the first chapter of the second book is titled From Charybdis to Scylla.

- 1937: in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, the sixth chapter is titled From Charybdis to Scylla [source insufficient].

- 2006: in James Joyce’s Ulysses, the entire ninth episode references this myth.

- 2006: in book 2, The Sea of Monsters, of Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson series.

Comics

- In issue number 102 published in 1967 of the Blek le Roc albums, Professor Occultis uses this expression to show that he, Blek, and Roddy were caught between an Indian tribe and the Red Lobsters.

- In the manga Saint Seiya, during the attack on Poseidon’s underwater sanctuary, the Andromeda knight battles General Io of Scylla, whose armor and powers refer to the mythological monster.

- In Mark Waid’s comic Irredeemable, Charybdis and Scylla are twin superheroes.

Film and Animation

- In episode 11 of Ulysses 31, Charybdis and Scylla are represented as two monstrous planets located in a vortex that, seen from above, resembles the symbol ∞. The first is of fire, and the second of ice.

- In the second episode of the animated series The Odyssey, Charybdis and Scylla are presented as a loving couple, victims of a curse by Circe. Charybdis has become a cave sheltering a whirlpool that swallows everything and Scylla has become a three-headed monster, with the two lovers unable to reunite. At the end of the episode, the two are reunited thanks to Ulysses and regain their original appearance.

- In season 4 of the series Prison Break, Michael Scofield and his team must obtain a memory card named “Scylla” which is accessed through six electronic keys (referring to the six heads of Scylla in Homer’s tale). The titles of the first two episodes of this final season also refer to this myth, as they are respectively titled From Charybdis… (# 4.01) and …To Scylla (# 4.02).

- Episodes 20 and 21 of the series Alias are titled respectively From Charybdis… (# 4.20) …to Scylla (# 4.21).

- In the film The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, the expression “to fall from Charybdis to Scylla” is spoken by the wizard Gandalf.

- In the film Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters, directed by Thor Freudenthal in 2013.

Music

- A song by the band Trivium on the album Shogun is also called Torn Between Scylla & Charybdis which means Torn between Scylla and Charybdis.

- A song by The Police discusses the bonds of marriage (Wrapped Around Your Finger) where Sting does not want to be caught between “the Scylla and Charibdes.”

Video Games

- In Halo 3, the Arbiter mentions this expression when, after killing the High Prophet of Truth and defeating the Covenant, the Master Chief and the Arbiter find themselves confronted with the Parasite.

- In God of War: Ghost of Sparta, Scylla is the very first boss of the game in Atlantis.

- In the video game Smite from Hi-Rez Studios, Charybdis and Scylla are part of the pantheon of gods accessible to players.

- One of the achievements in the video game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 is called From Charybdis to Scylla and is obtained by completing the level The Enemy of My Enemy…

Origin of the phrase

Ancient sailors having to take this passage were faced with an alternative: to pass by Charybdis or to pass by Scylla, and thus “to choose between Charybdis and Scylla.”

The well-known phrase “to fall from Charybdis to Scylla” seems to have been anchored in the language by Jean de La Fontaine with his fable The Old Woman and Her Two Servants, where the establishment of the expression may be more about the harmony of the verse. However, he was preceded by Gautier de Châtillon in his Latin novel the Alexandrian, with the mention: “…incidit in Scyllam cupiens vitare Charybdim…” (he falls on Scylla wanting to avoid Charybdis).