Black Friday is not the same as Black Thursday of 1929. Black Friday has a unique and somewhat complicated history. Every November, we are inundated with commercials for “World Consumer Day,” a veritable birth of the modern capitalist society. It’s tough to avoid Black Friday advertisements these days, what with all the emails, online billboards, and banners. Amazon stated in 2020 that it had surpassed the $4.8 billion sales milestone on this famous weekend, despite the fact that the weekend is responsible for feverish spending and, by extension, severe pollution and abuse in its logistic hubs. But what is the origin of Black Friday? This phenomenon seems to have several causes.

The modern tradition of Black Friday began in the 1960s

One of the knock-on effects of Thanksgiving is Black Friday. Americans meet on the fourth Thursday of November to give thanks to God for the year’s gifts. It was in the 1950s that American manufacturing managers saw a record absence rate on the day following Thanksgiving as workers called in sick to enjoy a longer holiday. The direct results of this event became known as “Black Friday“.

In the 1960s, the idea of Black Friday as a “day of sales” began to emerge. The phrase was adopted and popularized by the police, who dubbed the day’s traffic a “black day,” and by shops, which saw a spike in sales on the day since many workers stayed home. Then, the major players in mass distribution reclaimed the concept for profit, generating widespread publicity and ad fervor as a result.

It was Philadelphia police officers who coined this slang word to characterize the day that is notorious for traffic congestion and crowd movements due to the big discounts that many stores give over the long weekend before Christmas.

The city’s business owners sought to rebrand the day as “Big Friday” to distance themselves from the negative connotations of the original moniker, but the term failed to catch on. So Black Friday is still around.

By the end of the 1990s, not only had the name and idea of Black Friday expanded throughout the United States, but by way of American juggernauts Amazon and eBay, it had also taken hold in Canada, South Africa, Mexico, and the European Union.

However, there is another origin of the phrase “Black Friday” as well.

The first Black Friday, 1869

“Black” days have been used to describe days when bad things happened, for ages. And there have been several “Black Friday” occurrences.

The day of Black Friday being set aside for sacred consumerism is actually a rewriting of history. On September 24, 1869, the price of gold dropped precipitously, triggering a stock market collapse that severely affected the American economy. This “gold panic of 1869” was the first significant “Black Friday” in history.

The year 1869 marks the debut of the phrase. Gold’s value was boosted by the investments of Jay Gould and James Fisk. The result was a massive drop in stock prices and widespread economic chaos in the United States.

Retailers utilized this day to clear their shelves in an effort to get “out of the red.” They highlighted the excellent sales by writing in red ink, with the exception of the Friday following Thanksgiving, which was noted in black to emphasize the fact that they were finally profitable. Thus, the term “Black Friday” was born. Because this day would enable them to finally have a profitable turnover. The remainder of the year, they were regularly in deficit again.

1910 Black Friday

Friday, November 18, 1910, is another significant date in the history of Black Friday. The Women’s Social and Political Union was first established in the UK seven years earlier to fight for equal rights for women, including the vote. Beginning in 1905, members of the movement took direct action, such as disrupting political meetings, to make their voices heard.

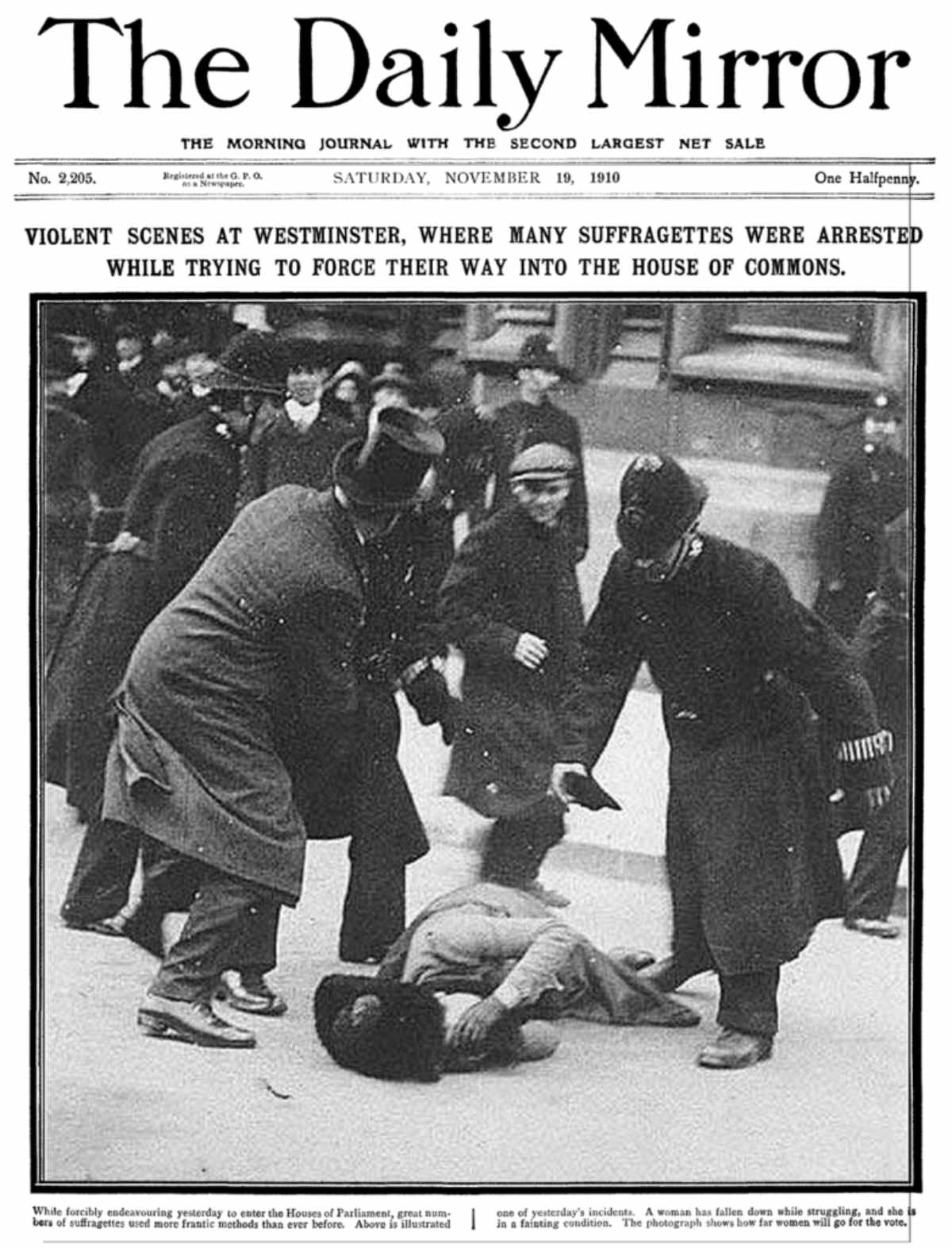

This group of women were dubbed “suffragists” or “suffragettes” by the media at the time. The group expanded and tried other strategies, eventually choosing to attack the British government in Westminster. Three hundred suffragettes attempted to storm the building on November 18, 1910. There were 119 arrests made, 29 sexual assaults reported, and two suffragettes died as a result of the police reaction.

The action was covered extensively the next day by major media, such as the Daily Mirror’s front page, which depicted a suffragette on the ground being thrashed by a police officer. Since this “Black Friday” incident caused such a stir, Winston Churchill decided to dismiss charges against the demonstrators.

Black Friday as it is celebrated in our modern consumerist cultures is not only different from its origins from year to year, but it also comes with its own set of injustices.

Ecological and social impact of Black Friday

Most online retailer workers work between twelve and sixteen hours a day on Black Friday. While this is great news for those on a tight budget, it also promotes wasteful spending and compels many to purchase things they don’t really need.

Customers are less likely to raise concerns about, say, Amazon’s dreadful working conditions at its fulfillment facilities if they perceive that the company is offering them a discount. Management may say they care about their employees, but in reality, they treat them like replaceable commodities, including ignoring workplace injuries.

Worse, Black Friday symbolizes a more systemic societal problem: the idea that a person’s worth is not determined by their talents, like compassion or interaction with others, but rather by the commodities they amass. In other words, shopping has made us who we are. These mind-boggling numbers illustrate that the insatiable need for expansion on which capitalism thrives is damaging not merely to individuals but to the whole world.

The next steps

Knowledge of the problem’s scope is necessary but insufficient. There are answers out there, thankfully. Despite the fact that we live in a consumer-driven world, this does not imply that we must fall for the persuasive appeals of marketing.

Black Friday and the culture of excess consumerism it promotes might be seen as at odds with the minimalist lifestyle. This line of thinking encompasses a wide range of practices, including reducing one’s consumption without compromising one’s morals, keeping rather than discarding, shopping secondhand, etc. According to Ryan Nicodemus, the founder of The Minimalist movement, minimalism is not about getting rid of your belongings but about taking back control of your life, stopping doing what you’re told, and actually determining what you want to do.

Additionally, new projects are springing up. Many businesses choose to stay closed as a protest against this consumerist trend. In 2019, the Climate Strike, and the Feminist Strike groups hosted an anti-consumerist festival, the Black Free Day, in Lausanne, Switzerland. The event was devoted to barter and trade, and included free concerts and improvised competitions.

On the same day, hundreds of activists around the world participated in the Extinction Rebellion collective’s Block Friday by blocking the major entrances to retail malls. The Green Friday has been celebrated annually in several countries since 2018 as a consumer awareness day with the mission of encouraging moderate spending and putting the decision-making power back in the hands of the customer.

Bibliography

- Black Friday, Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary

- “Around and About”. The Shortsville-Manchester Enterprise. 1961.

- “Retailers riding Black Friday’s cyber wake”. Radio New Zealand. 2018.

- They treat us like disposable parts | Business Insider India

- Violent scenes at Westminster, The Daily Mirror, 19 November 1910.