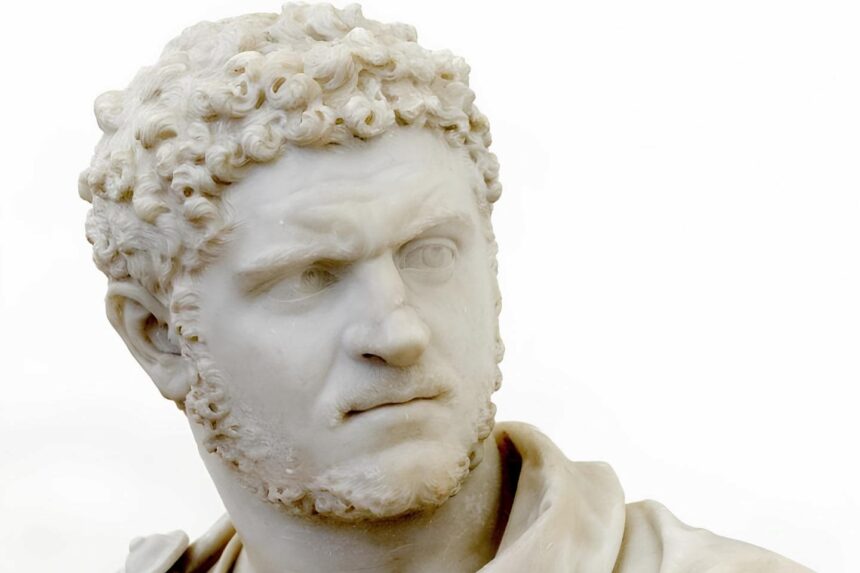

Caracalla: Who Expanded Roman Citizenship

Caracalla (188–217 AD), born Lucius Septimius Bassianus and later named Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, was a Roman emperor from 211 to 217 AD. He is one of the most infamous Roman emperors, known for his brutal reign, military campaigns, and the infamous Caracalla's Baths in Rome.