Pepin the Short, son of Charles Martel, was able to depose the last Merovingian monarch and establish a new dynasty at the head of the Frankish realm because of his position as mayor of the palace and the renown of his family. However, his son, the illustrious Charlemagne, whom the Pope crowned Emperor of the West in 800 after a string of military triumphs in favor of Christianity, was the one who gave this dynasty its name. The Carolingian Empire was short-lived, however, collapsing in 843 with the partition of Verdun between Charlemagne’s three grandchildren. The imperial title lasted until 924, and when Louis V of France passed away in 987, the Carolingian dynasty came to an end.

When and How Did the Carolingian Dynasty Begin?

The Frankish aristocracy of the Merovingian period suffered the same fate as the other barbarian kingdoms established after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 7th century. As time went on, the legitimate Merovingian kings, who were called “lazy kings” (Roi fainéant), lost power and were replaced by the noble mayors of palaces.

Even though they were originally just the kings’ stewards, they eventually grew so powerful that they could actually remove and replace the kings themselves.

Childeric III, the last representative of the Merovingians, was deposed in 751 by Pepin the Short, mayor of the palace of Neustria and son of the famous military leader Charles Martel who had stopped the Muslim expansion in Poitiers in 732 (See: The Battle of Tours and The Reconquista).

Pepin the Short, also known as Pepin III, founded the Carolingian dynasty after Pope Zachary officially crowned him king of the Franks. He left the kingdom to his son Charlemagne, also known as Charlemagne, who expanded it into an empire after his death in 768. Between 751 and 771, Charlemagne and his brother Carloman I ruled jointly.

Key Dates in the Carolingian Empire

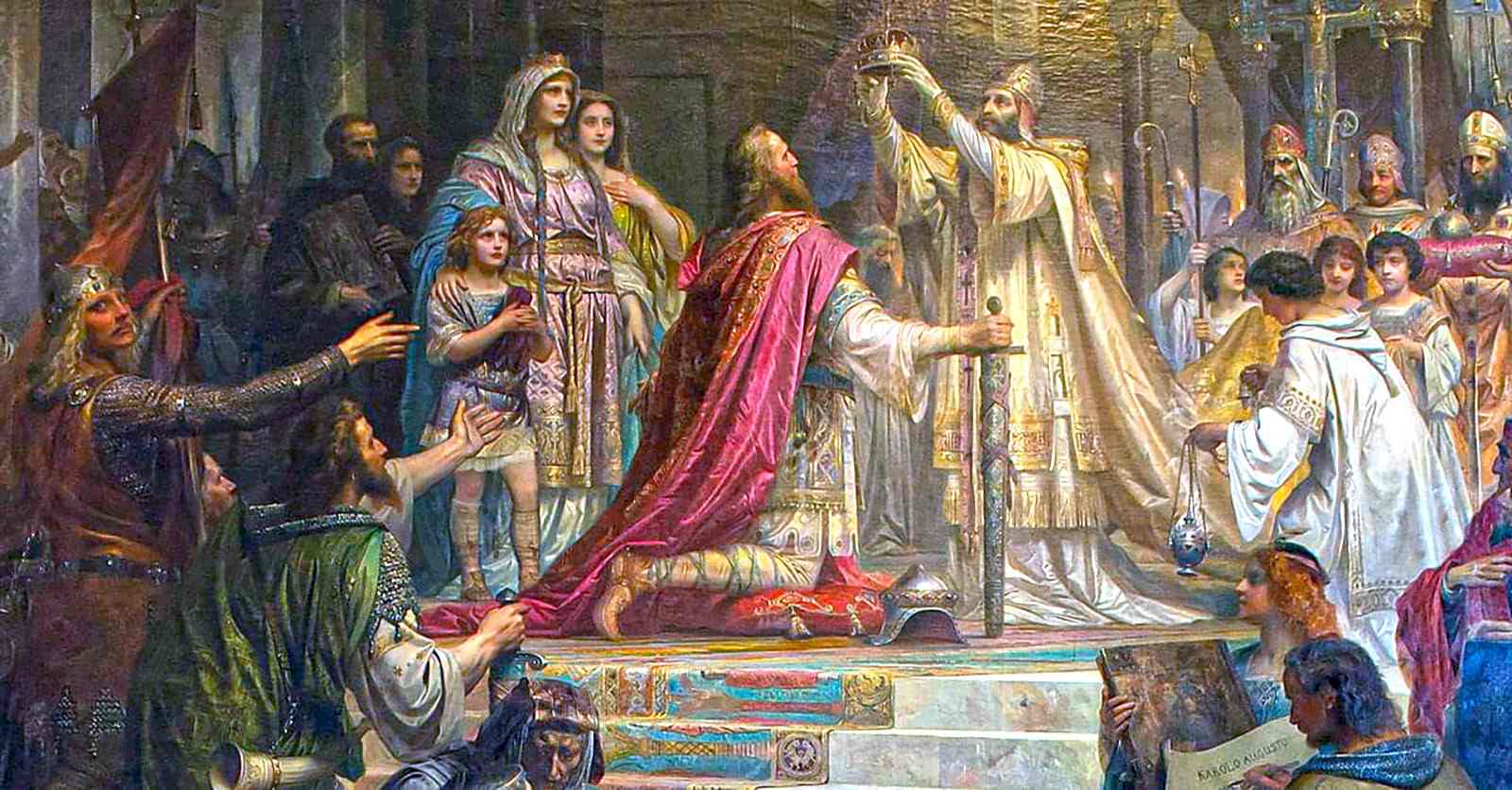

During the first three decades of his reign, Charlemagne expanded the Frankish empire through a series of military victories, mainly against the Saxons and the Lombards, with the assistance of the pope. In 800, he was anointed emperor in Rome under the name Charlemagne after rescuing Pope Leo III from an assassination attempt. He then set about reconstructing the Western Empire.

After the death of Charlemagne in 840, the so-called Carolingian Empire (a name derived from Charles Martel and Charlemagne) was split into three parts. Louis I, also known as Louis the Pious, inherited it from his father in 814. The three surviving sons of Louis (Charles the Bald, Lothair I, and Louis II) negotiated a violent division of the Carolingian Empire and signed the Treaty of Verdun in 843.

The Carolingian Empire collapsed when it was divided into three separate kingdoms. Nevertheless, the Emperor of the West title survived until Berengar I’s death in 924, at which point it was no longer used.

Territories Conquered by Charlemagne

When his father, Pepin the Short, passed away in 768, Charlemagne had already completely incorporated the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony into the realm.

Charlemagne, at the invitation of the pope, launched an offensive against the Lombards in 773 and soon prevailed, eventually annexing the northern part of Italy up to Rome. He used this victory to launch an all-out assault on the Saxons in 776, the last indigenous pagan group in the area.

To finally defeat them in 785, several military campaigns were necessary, one of which Widukind led. Charlemagne’s 778 campaign against the Saracens resulted in a crushing loss at the hands of the Christians in the Battle of Roncesvalles Pass.

Later conquests, however, created what is now known as the “Spanish March,” and efforts against the Frisians, Bretons, Bavarians, and Avars in the years 780–800 pushed the Carolingian Empire even farther west.

When Charlemagne passed away in 814, the area of the imperial dominion was about 385.000 square miles (1 million sq km), having doubled during his period.

How Was the Territory of the Carolingian Empire Ruled?

Charlemagne was not only a conqueror and military genius, but also a reformer and highly productive king. 300 provinces made up the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne’s religious and secular commands were carried out over his vast realm by “missi dominici” (Latin for “envoy[s] of the lord [ruler]”) which were institutions with two heads (a count and a bishop).

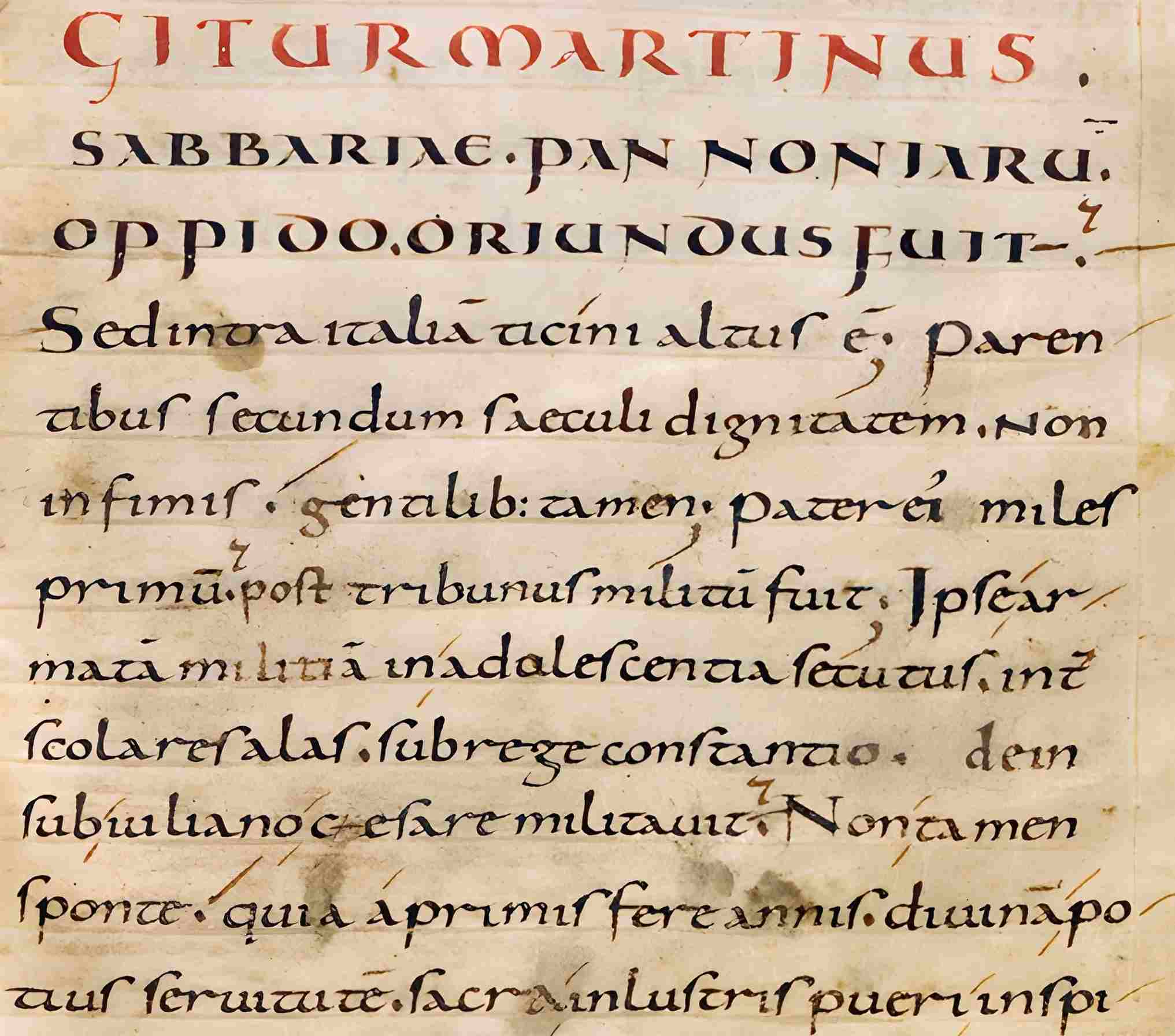

Mathematics and grammar were taught in schools set up in each bishopric, and a uniform form of medieval Latin script was introduced.

The Carolingian minuscule, a new kind of writing, was developed to make books easier to read. Additionally, a monetary reform was implemented to switch from gold to silver as the metal of choice for coinage. The goal was to make it simpler for business deals to be done, allowing commerce to flourish.

Roads were kept in good shape, and farmers’ markets were given the green light, among other things. Libraries, artworks, and monuments flourished under Charlemagne’s reign, ushering in a period known as the “Carolingian Renaissance.”

What Language was Spoken in the Carolingian Empire?

The Salian Frankish nobles, initially from the Rhine River but later moving southwest, established the Carolingian Empire after establishing a foothold in Gaul after the collapse of the Roman Empire. The Franks, under Clovis’ rule, soon adopted aspects of Gallo-Roman culture and eventually abandoned their pagan religion in favor of Christianity.

Even though the Merovingians spoke Old Frankish, the Carolingians under Charlemagne adopted a close dialect called Rhenish Frankish, which became the official language of the capital of the Holy Roman Empire at Aachen.

What Was the Place of Religion in the Carolingian Empire?

The covenant struck between the Carolingian monarchs and the pope to support each other was a defining feature of the Carolingian Empire and its long partnership between politics and religion.

Charlemagne ordered the baptism of all infants under the age of one in the bishoprics, instituted the payment of tithes across the kingdom as early as 779, and founded several monasteries.

Paganism was outlawed, and Christian conversion was mandated in the conquered areas, particularly in Saxony. Charlemagne, against Rome’s opposition, commanded the addition of the Filioque (a Latin term meaning “and from the Son”) to the Nicene Creed during the ensuing dispute between the Roman and Greek churches over the doctrine of the Trinity. Theology developed strongly during the period of Charlemagne.

How Did the Carolingian Empire End?

When Charlemagne’s heir, Louis the Pious, died, his sons fought over who would succeed him. The sons intended to split up the Carolingian Empire, while the clergy wanted to keep it as one.

Louis’ oldest son, Lothair, believed he would rule on his own. Charles the Bald received West Francia, Lothair I received Middle Francia, and Louis II received East Francia according to the Treaty of Verdun signed in 843, which ended years of civil strife.

There was a de facto dissolution of the state their grandfather Charlemagne had established. These three realms were not self-sustaining due to external factors like the untimely assaults of the Vikings and the Arabs, the squabbles between brothers and their offspring, and the frequent and unexpected deaths of rulers. The Carolingian dynasty and its royal line ended in the middle of the 10th century.

What Do the Byzantine Empire and the Carolingian Empire Have in Common?

Both the Byzantine and Carolingian empires were Christian and ruled from Constantinople and Aachen, respectively. In both instances, the emperor led the armed forces and ensured the country’s religious harmony by means of military conquest. The governors, sometimes known as missi dominici, were responsible for implementing policies in several regions. The two dynasties had similar priorities when it came to the advancement of culture and learning.

KEY DATES OF THE CAROLINGIAN EMPIRE

October 22, 741 – Death of Charles Martel

Charles Martel was a notable person in the 8th century, serving as mayor of the palaces of Neustria and Austrasia and also as a prominent statesman and military commander. After defeating Umayyad forces attempting to take over Francia at the Battle of Tours (also called the Battle of Poitiers) in 732, he gained international renown and the papacy’s attention. When he passed away, he was given the honor of being buried in the royal church of Saint-Denis.

November 751 – Pepin the Short, King of the Franks

Pepin the Short, Charles Martel’s son, ousted Childeric III, king of the Merovingians, and assumed the throne following his father’s death. This was ten years after Martel’s own death. The pope, Zachariah, supported his claim to the throne, and he became king of the Franks in 751. The Merovingian Dynasty came to an end with this event, ushering in the new Frankish bloodline known as the Carolingians.

July 28, 754 – Pepin the Short was Once Again Crowned

Pepin the Short, at the behest of Pope Stephen II (who succeeded Zachary in 752), launched a victorious military expedition in Lombardy. Land was donated by Pepin, and the Papal States were officially established when the Treaty of Quierzy was signed in 754. The pope recognized his loyalty by reinstating his position as king of the Franks and bestowing upon him the title of Patrice of the Romans. During this time, the ties between the pope and the new monarchy were tightened even further.

September 25, 768 – Death of Pepin the Short

Pepin the Short, who died at the age of 54 due to sickness, spent the last years of his reign consolidating the kingdom in the South through the conquests of Septimania in 759 and Aquitaine in 768. He was laid to rest at Saint-Denis, much like his father. Carloman and Charlemagne, his sons, argued over how to divide the realm when he died.

December 4, 771 – Charlemagne Took Power

Charlemagne took full control of the realm after Carloman’s sudden death in 771, and taking the opportunity to oust his infant nephews, who were eventually imprisoned for life in a monastery. The Archbishop of Sens, Wilcharius, recognized him as the only ruler of the Franks.

774 – Charlemagne Confirmed the Papal States

Charlemagne formally acknowledged Pepin’s contribution to the Roman Catholic Church before the newly installed Pope Adrian I in Rome. The papacy’s temporal rule over the Papal States was recognized. The latter will continue to grow via further gifts and invasions.

August 15, 778 – Death of Roland at the Pass of Roncesvalles

It was in 778 when the famous warrior Roland, who had been guarding the Frankish border with Brittany, was tasked with leading an expedition against the emirate of Cordoba in Spain. At the Battle of Roncesvalles, this close friend and rumored nephew of Charlemagne was killed by an unexpected assault by the Vascons (Basques).

781 – Alcuin Took Charge of Charlemagne’s School

In 781, while visiting Rome, the English philosopher and theologian Alcuin met Charlemagne, who asked him to live in Aachen, the imperial capital. He rose rapidly to become the most trusted counselor to the Emperor and the leader of the Palatine School, which Charlemagne had created to educate his top officials. As a result, many episcopal schools and libraries were established across the enormous realm, ushering in the “Carolingian renaissance.”

799 – Charlemagne Annexed Dalmatia

Dalmatia was a crucial province of Croatia because of its location between the Byzantine and Carolingian empires. Charlemagne invades in 799 and firmly conquers the region by 803. This invasion by the Franks leads to a naval conflict with Constantinople that is only resolved with the signing of the Pax Nicephori in 812.

December 25, 800 – Coronation of Charlemagne

As a result of Charlemagne’s repeated victories, the Carolingian empire came to cover almost the whole Christian West. Political and religious leaders began to consider the possibility of an empire as a result of the ruler’s absolute authority. Charlemagne was proclaimed Emperor of the West in 800 after a failed coup against Pope Leo III in 799. The Byzantine Empire did not acknowledge this coronation because it saw it as illegitimate.

January 28, 814 – Death of Charlemagne

The Western Roman Emperor Charlemagne passed away at the age of 72 in the city of Aachen from what was likely a case of severe pneumonia. His son Louis the Pious took the imperial title after him, but that only sparked a battle of succession for power.

June 22, 841 – The Division of Charlemagne’s Empire

The Auxerrois area was the site of the war between Charlemagne’s grandchildren for control of the Empire. The true successor, Lothair, was defeated by his brothers, Louis the German and Charles the Bald. In 843, he was forced to sign the Treaty of Verdun, which gave the French-speaking half to Charles and the German-speaking part to Louis. It was during this war that the seeds for Germany, France, and Italy were planted.

February 14, 842 – Oaths of Strasbourg

Charles the Bald and Louis the German, Charlemagne’s grandsons, exchanged “Oaths of Strasbourg.” They joined forces to take on their elder sibling, Lothair, Emperor of the West, and they did so with this covenant of mutual help. This is the first official document to be written in a vernacular other than Latin.

Both Louis the German and Charles the Bald take the oath, but Louis does it in Romance while Charles does it in Tudesque, the ancestor of German. Lothair was defeated on June 25, 842, by the two allied brothers at Fontenay-en-Puisaye in modern-day Burgundy.

843 – The Belgian Territory Divided by the Treaty of Verdun

It was officially split between France and Lotharingia the day after the treaty was signed. Northern Flanders fell to Charles the Bald, while southern Wallonia was added to Lothar I’s realm. However, a few years later, the Holy Roman Empire would be given credit for the latter.

November 22, 845 – Independence of Brittany

Near Redon, the Breton Nominoe triumphed in a ball battle against Charles the Bald’s Carolingian army. This loss meant the end of the king’s attempt to conquer Brittany. Brittany broke away from the monarchy and established its own government. It would remain so for nearly 7 centuries.

April 10, 879 – Death of Louis the Stammerer

After a long illness, the 33-year-old monarch of West Francia passed away at Compiègne. King of France for only 16 short months, Louis the Stammerer was also known as King Louis II the Lazy. Louis III and Carloman, two of his sons, would go on to rule as monarchs of Neustria and Aquitaine, respectively.

November 28, 885 – Beginning of the Siege of Paris by the Normans

Parisians had been fending off the Vikings since the mid-9th century, who were not afraid to ravage the city as they did in 856. The Normans tried something new this time around and laid siege to the city. Because of Eudes, Paris was able to hold out for over two years. It wasn’t until Charles the Fat paid a huge ransom that fighting stopped.

January 13, 888 – Death of Charles the Fat

As a result, Charles the Fat, King of the Franks and Emperor of the West, passed away at Neidingen without a direct successor. As a reward for his bravery in repelling the Norman invasion of West Francia, Robert the Strong named his son Eudes as his heir. On February 29, he was anointed king of the West Franks, and he ruled until 898.

July 20, 911 – Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte

A century after racking up victories and establishing a foothold in Neustria, the Normans were beaten at Chartres by Charles the Simple. The latter was able to exert his authority and initiate talks with the “invaders” as a result of the changing circumstances. The end result was the establishment of the duchy of Normandy. In return for the King of France’s acknowledgment, the Norman Rollon gained control of this area. Additionally, he said that he would become a Catholic. The Normans quickly expanded their area after becoming French, which at the time included roughly what is now Upper Normandy.

October 7, 929 – Death of Charles the Simple

The French monarch passed away while in Herbert of Vermandois’ captivity at Peronne. Although he had reigned as king since 893, the Robertians had ousted him and thrown him in jail in 922. Robert I took over after him.

March 2, 986 – Death of Lothar III

Following a fulgurating pandemic, the Frankish king died at the age of 45. The cathedral of Saint-Rémy in Reims served as the site of his burial. Louis V, his son, took over after him. There was just one year under his rule.

References

- Davis, Jennifer (2015). Charlemagne’s Practice of Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1316368596.

- Joanna Story, Charlemagne: Empire and Society, Manchester University Press, 2005 ISBN 978-0-7190-7089-1

- The paradox of the past in the crisis of the Carolingian Empire – After Empire”. arts.st-andrews.ac.uk.

- Wickham, Chris (2005-09-22). Framing the Early Middle Ages. Oxford University Press. p. 674. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199264490.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-926449-0.

- King, P. D. (1987). Charlemagne Translated Sources. p. 124. ISBN 978-0951150306.

- Kramer, Rutger (2019). Rethinking Authority in the Carolingian Empire: Ideals and Expectations During the Reign of Louis the Pious (813-828). pp. 31–34. ISBN 9789048532681.