From 1762 until 1796, Catherine II (also known as Catherine the Great) ruled as Russia’s imperial ruler. After overthrowing her husband, Tsar Peter III, in a coup, she furthered the Westernization of Russia that her predecessor, Peter the Great, had started. She expanded her kingdom at the cost of the Turks and the Poles and overhauled the government, all while maintaining her reputation as an “enlightened despot” who corresponded with the Enlightenment intellectuals. Over the course of her lengthy reign (34 years), Russia’s cultural influence spread across Europe, but at home, the political climate hardened significantly. “I leave it to posterity to assess impartially what I have done,” Catherine the Great could have said at some point in her reign.

Becoming Empress of Russia

The future Catherine II of Russia, Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, was born on May 2, 1729, in Stettin, Pomerania, to a Prussian officer father and a stylish princess mother. Although she was often ignored by her parents, she flourished under the guidance of her French governess, and by the time she was fifteen, the Empress Elizabeth had urged her to choose the future Tsar Peter III as her husband. In February of 1744, the lad, then 16 years old, was introduced to the princess. He was an avid fan of Prussian King Frederick II, enjoyed hunting, and was also a doll collector.

After being coerced into marrying Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, nephew and successor of Empress Elizabeth of Russia, grandson of Peter the Great, on August 21, 1745 in St. Petersburg, Sophie converted to Orthodoxy and became known as Catherine II. The young woman’s dreams swiftly turned into a nightmare once she married her husband, who beat her, played the violin at 3 a.m., and got drunk first thing in the morning, among other things. After eight years of marriage and no children, Elizabeth took matters into her own hands and arranged for a liaison with a young lieutenant known as Saltykov, nicknamed “the handsome Sergei.” She gave birth to the future Paul I, who was immediately taken from her and whom she would not see until forty days later.

On January 5, 1762, Peter III ascended to the throne and, in order to save his hero Frederick II of Prussia, withdrew from the alliance with France and Austria. A black cloud hangs over Catherine II’s future, as her husband plans to imprison her and replace her with his lover. He was unpopular and he was moving forward with plans to end serfdom and the practice of private chapel closures. The tsar abdicated, was imprisoned, and was discovered dead in June 1762, reportedly of hemorrhoidal colic but in reality killed when his officers of his guard rebelled and pledged devotion to Catherine.

On September 22nd, at the historic Moscow cathedral, Catherine was declared Empress and crowned. She retained the statesmen who had been active under Empress Elizabeth and Peter, as well as Chancellor Vorontzov, and learned the alarming state of her country: a deficit of seventeen million rubles for a nation of one hundred million people, along with complaints of corruption, extortion, and injustices.

The Reforms of Catherine II

Catherine II, as Russia’s monarch, was eager to carry on the tsarist strategy of expanding the country’s splendor. The landed nobles owned vast estates and held legal authority over the serf population. Catherine II began developing agricultural methods by dispatching specialists to assess the soil and suggest new crops. For ranchers, her assistance meant being able to afford new tools and methods for raising cattle. The company handled mining activities and sent geologists to the mines. Moreover, she established the first mining school in St. Petersburg, complete with a working mine beneath.

She facilitated the growth of commerce by letting private citizens establish companies and welcoming immigrants like Germans and Moravians. Linen, leather products, furniture, and ceramics were only some of the newer businesses to emerge. Catherine II requested that English Admiral Charles Knowles construct warships due to a dearth of domestic shipyards.

Russian exports to Manchuria and China increased when she eliminated export taxes on materials including timber, hemp, linen, leather, furs, clothes, and iron. Cotton, tobacco, silk, silver, and tea were among the many goods Russia imported in return. In order to pay off the debts incurred by the then-Empress Elizabeth and turn a profit, Russia expanded its manufacturing capacity from 98 factories during Peter the Great’s reign to 3,160 factories by the conclusion of Catherine II’s reign.

In 1767, in response to peasant complaints, Catherine II set additional regulations. The landed aristocracy was unhappy, and Pugachev’s peasant insurrection in 1773–1774—and Pugachev’s own public execution in Moscow in 1775—were the direct result. Therefore, in 1785, it established a Charter of the Nobility (also called Charter to the Gentry) where the privileged can take part in public affairs, have the right to elect a provincial marshal, participate in general assemblies, and enjoy liberties like not being subject to corporal punishment or execution without a trial, not having to pay taxes, establishing businesses and industries, and maintaining their land holdings with the established peasants. The number of serfs and the landowners’ control over the peasants grew accordingly. In retrospect, Catherine II felt most sorry that she was unable to put an end to serfdom.

Catherine the Great: Protector of arts and letters

Her desire to build was pressing, but before beginning actual building, she had architects create scale models of the outside and inside. She even drew up plans for a miniature city, complete with fire-safe plazas, office buildings, and retail establishments set back from the main drag. St. Petersburg, which was supplemented with palaces and monuments created by French and Italian artists—especially the Pavlovsk Palace in the city’s southern section—joined Sevastopol and Kherson as new urban centers.

The Russian leader also expressed concern about the decline in youth literacy. In 1764, she created the Statute of Schools for all of Russia after transforming a convent in St. Petersburg into a boarding school for aristocratic and middle-class girls called the Smolny Institute. Throughout the city, a school was established in each ward, with each under the charge of two educators. Six educators were needed to staff a major school in a regional city.

Motivated by an interest in the creative process, she founded the Academy of Fine Arts. A “world tour of masterpieces” to the world’s biggest cities was the first stop on the curriculum for the youngest students, who started school at age 5 or 6. The dancing school was updating its facilities to better compete on a global scale. As time went on, Russia became known as the “home of ballet,” and today many of the world’s top dancers (Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov) hail from Russian ballet academies. This institution followed traditional practices by providing free instruction, admitting students as early as age 10, and keeping them for an average of nine years.

It also normalized the practice of having students see naked models during anatomy lessons. The resources available to improve public health were, indeed, inadequate. Noting that smallpox was the leading cause of infant death, Catherine the Great established Russia’s first medical school in 1763 to educate future physicians, surgeons, and pharmacists, and she enlisted the services of the eminent Scottish physician Thomas Dimsdale to administer a massive vaccination program.

In 1768, Catherine II stepped forward as a medical care pioneer. She bought up properties in Moscow and St. Petersburg with the intention of turning them into hospitals after the success of the vaccine. When she restructured the provinces in 1775, she mandated that every capital city and every district with 20,000 to 30,000 people have access to medical care in the form of a hospital staffed by physicians and surgeons as well as medical students.

Catherine the Great’s diplomacy

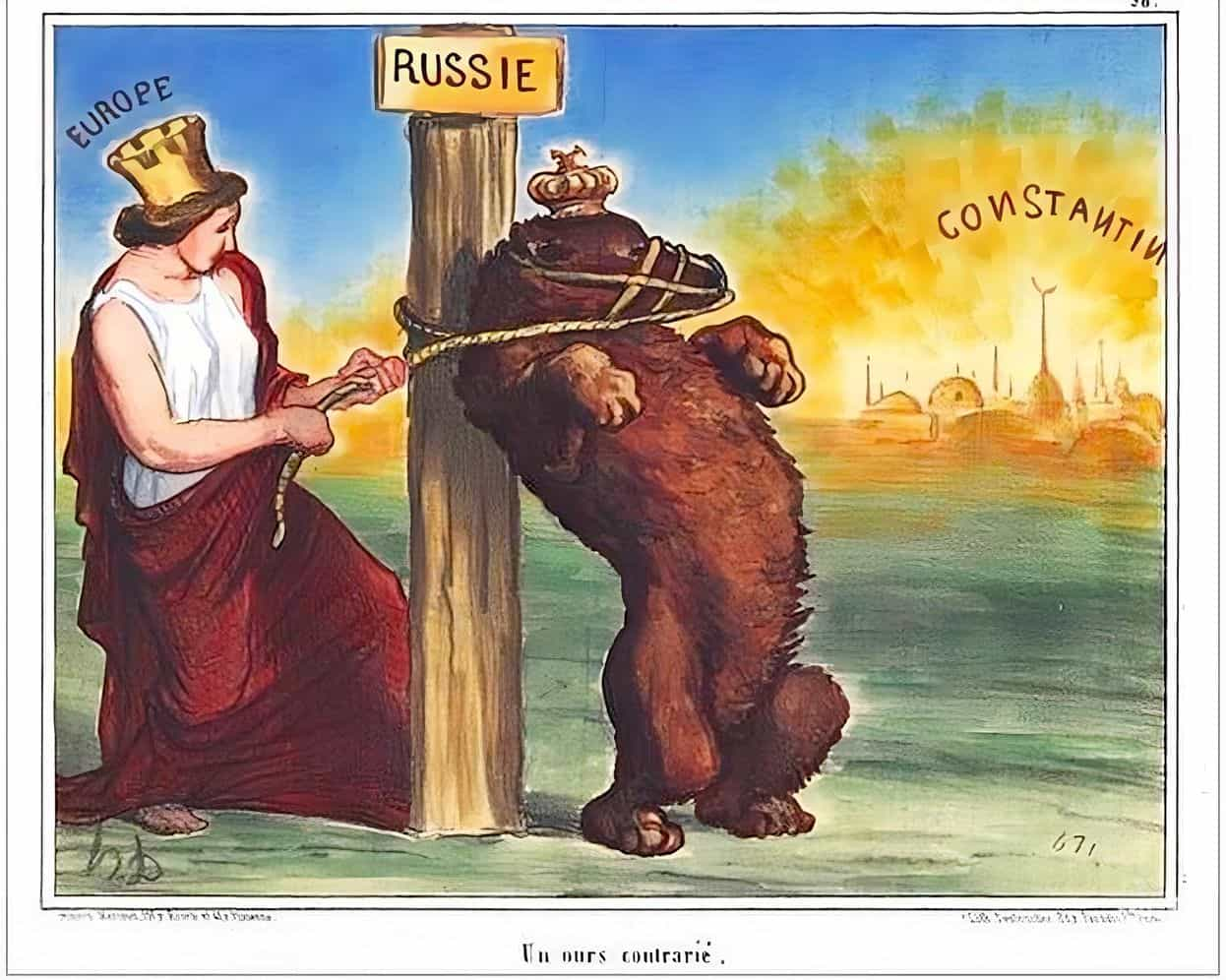

Catherine II planned to increase her territory by moving westward into the Black Sea, the Baltic, and Central Europe. Her correspondence with other monarchs, notably Frederick II of Prussia, was where her foreign policy was carried out.

However, the Prussian king did not make the empress’s job easier. True, Catherine II had her ex-lover Poniatowski installed as king of the Polish republic in an effort to keep Russia’s dominance over Poland intact. Using the tensions between Russia and the Turks, Frederick II of Prussia split Poland into three in 1772, giving Russia, Prussia, and Austria control over one section each. After a second partition of Poland in 1793 that favored Russia, Poland ceased to exist as a nation-state in 1795, despite a Polish uprising.

In 1769, the Ottoman Empire issued a formal declaration of war. Catherine II took revenge on the Turks in 1770 by destroying their naval fleet. Eventually, the Porte sought peace with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774. As a result, in 1783, Russia gained independence in Crimea and freedom of passage in the Black Sea. But in 1786, the Sultan restarted the war and Russia finally won the Treaty of Jassy in 1792, which is how Odessa and its port came into being. Russia, however, was not content, and the Turks continued to block military vessels from passing through the straits.

The monarch, who had been influenced by the Enlightenment, was alarmed by the revolutionary ideals that had originated in France. She went from being an educated ruler to a blind supporter of the counter-revolution by just opening her wallet.

Catherine II’s personal life

She was neither inhuman nor heartless, yet her emotional life was devoid of depth. She had numerous boyfriends since her love for her grandchildren was inadequate, and her lovers would rise to the ranks of minister, general, ambassador, and prince.

Around seven in the morning, she rose, reviewed the news, and met with her cabinet. The court gathered around a beautifully set table at midday, and the empress used the occasion to advocate for the growth of the Imperial Porcelain Factory. She enjoyed boiling meat and was responsible for introducing the potato to Russia, despite the fact that it was often regarded as a devil’s herb.

In the afternoons, she would join the courtiers for a game of cards, where she would lose unimaginable amounts, while billiards would be her forte. Evenings included performances such as Monday’s Comédie Française, Tuesday’s Russian comedy, Wednesday’s tragedy, and Thursday’s opera. She saved her weekends for the masked ball, and since she was so enamored with opulence, she would often change her attire three times before the big event. She seldom wore the same outfit again, both in her daily life and during formal events, when she wore a military dress tailored for ladies by French fashion designers.

She maintained up an extensive contact with many of the world’s most renowned thinkers and authors, including Voltaire and Diderot (the latter of whom traveled to Russia at the ripe old age of sixty). After Voltaire’s death, Catherine II repurchased his complete library and relocated it to the Hermitage, an extension of her winter residence, where it remains to this day. The National Library of Russia, which began with a single volume and has now expanded to approximately 38,000, now stores these books in a secure location under constant surveillance.

She frequented the baths, taking hand-picked members of her court with her many times a week. She commissioned a cold baths to be constructed in her preferred residence, Tsarskoye Selo, with chambers that were tiled with jasper. She had the Amber Room constructed at the same address. In this chamber, the empress relaxed and healed thanks to the calming and curative characteristics of amber, which is why six tons of this stone, sometimes referred to as the “eighth wonder of the world,” were required to create it.

Catherine II’s romantic life was exciting, and she did much for her lovers: she spent ninety-two million rubles on her favorites, whereas the official budget was just seventy million rubles per year. It’s possible that Paul I’s biological father was her first lover, and that he abandoned her for the Saxon diplomat and future Polish king, Stanislas Poniatowski. However, she rapidly comes to value her time with him beyond everything else. Then Orlov arrives, a young military man of twenty-five who is as talented in love as he is in battle.

Affair with Potemkin and the end of his reign

She was 45 years old when she started dating Grigori Potemkin, a soldier and Orlov’s younger brother. He was her go-to advisor, a guy of education and experience to whom she felt comfortable confiding state secrets and pressing matters. She wiped off his gambling debts, gave him the Tauride Palace in St. Petersburg, and elevated him to the rank of prince during their two-year romance. In order to maintain his standing with the Empress, Potemkin mimicked Madame de Pompadour by selecting her future suitors. After being checked up by the doctor, the countess gives them a cultural and sexual performance evaluation. The one who is picked will be elevated to a position of prominence at court, eating at the empress’s table and standing at her side at important events, if he accepts.

A few years later, a man named Alexander Lanskoi arrives; he is 25 years old and will pass away a year later. A year later he allegedly overdosed on aphrodisiacs or was poisoned by Potemkin, who was envious of him. The youngest of his favorites, Zubov, would be only twenty-two at the time.

At the age of 67, Catherine II passed away at Tsarskoye on November 17, 1796, due to a heart attack. Her son, Paul I, ascended to the throne, despite her wishes that her grandson Alexander would rule instead.

Bibliography:

- 1981). Russia in the Age of Catherine the Great. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300025156.

- (1993). Catherine the Great: A Short History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05427-9.

- Rounding, Virginia (2006). Catherine the Great: Love, Sex and Power. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-179992-2.

- Streeter, Michael (2007). Catherine the Great. Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905791-06-4.

- Marcum, James W. (1974). “Catherine II and the French Revolution: A Reappraisal”. Canadian Slavonic Papers. 16 (2): 187–201. doi:10.1080/00085006.1974.11091360. JSTOR 40866712.

- Nikolaev, Vsevolod, and Albert Parry. The Loves of Catherine the Great (1982).

- Ransel, David L. The Politics of Catherinian Russia: The Panin Party (Yale UP, 1975).