The Celts are Indo-European peoples originating from the Danube Valley, who settled in much of Europe in antiquity. These tribes spoke the same language, with variations, and shared certain religious beliefs. They were the disseminators of the Iron Age civilization in Western Europe. Most historians refuse to speak of a “Celtic civilization,” instead referring to a Celtic world with linguistic and cultural similarities. Organized into countless tribes and fluid federations, the Celts of Gaul were industrious and ingenious farmers, as well as fierce warriors and savvy merchants, in contact with the ancient Mediterranean world.

- What Are the Origins of the Celts?

- The Expansion of the Celts: Hallstatt and La Tène Periods

- History of the Celts in Gaul

- Economic Activity

- Celtic Art and the Vix Grave

- A Warrior Aristocracy

- Religion of the Celts

- The Role of Druids and Bards

- Agriculture and Salt

- Celtic Craftsmanship

- Celtic Gaul: A Mosaic of Tribes

- The Romans Enter Gaul

What Are the Origins of the Celts?

The Celts were an “Indo-European” people originally from Central Asia, who settled in Southern Russia around 2500 BCE. At the beginning of the Bronze Age, their military aristocracy conducted numerous plundering expeditions to the Near East and Greece, then the group dispersed around 2000 BCE. Some of the Celts moved towards the North Sea, while others headed towards Central Europe (Bohemia), where they developed the bronze industry.

Around 1250 BCE, the Celts in Europe gave rise to the so-called “Urnfield” civilization, named for the large number of funerary urns containing the ashes of the deceased. These burial sites also reveal great skill in crafting ceramics and long, straight swords. Urnfields began to appear in France around 1200 BCE.

The Expansion of the Celts: Hallstatt and La Tène Periods

Around 1000 BCE, the Celtic civilization of Hallstatt developed in the Austrian Alps, named after a village near Salzburg where around 20,000 objects were found in numerous tombs. These artifacts reveal the wealth of the Celtic people, who produced refined jewelry, decorated vases, and mastered ironwork to create formidable weapons. This warrior people expanded westward to southern Germany, Switzerland, and, by the early 8th century BCE, into present-day France.

By 500 BCE, at the beginning of the Iron Age in Northern Europe, the Celts occupied all of Northern and Western Gaul, from Carcassonne to Switzerland, and founded the La Tène civilization (named after a village near Neuchâtel, where large tombs containing two-wheeled chariots were found in 1881). This people built wooden and earthen houses grouped on fortified oppida, constructed places of worship, and fought using chariots, iron swords, and helmets.

The Celts of La Tène began, in the 5th century BCE, the conquest of new territories further south: they subdued part of Provence, while in 390 BCE, Ambicat, king of the Bituriges Celts, captured Northern Italy (later known as “Cisalpine Gaul”). The Senones of Brennus boldly confronted the Romans and sacked the city of Rome (390 BCE), sparing only the Capitol thanks to sacred geese whose cries alerted the defenders.

Other Celts pushed further east: in the early 2nd century BCE, they settled in the Balkans and sacked Greece. They then founded a kingdom in Thrace, on the shores of the Black Sea, and in Asia Minor (Galatia, the land of the Galatians). Indeed, this term used by the Greeks to describe the Celts likely meant “those from elsewhere” or “the invaders.” Cato the Elder translated it as “Galli,” which became “Gauls.” Most of the Gauls were thus, in the end, Celts occupying the western part of Europe.

History of the Celts in Gaul

In the 4th century BCE, the Celts continued their conquest of the Rhône Valley and targeted Marseille. The city resisted the invasion to maintain its independence. Meanwhile, the Allobroges settled north of the Isère, the Voconces north of the Ventoux, the Tricastins in the Drôme Valley, the Cavares between Valence and Avignon, the Arécomices from Orange to Narbonne, and the Tectosages from Narbonne to Toulouse. According to some sources, a certain Ambigat, king of the Bituriges (Bourges), dominated most of the central Gaulish peoples.

Settled in southern Gaul, the Celts developed an “oppida civilization,” with oppida like Ensérune near Béziers or Entremont (north of Aix-en-Provence). They facilitated trade both northward, along the Rhône, and westward, along the Garonne, towards Carcassonne, Toulouse, and even the Atlantic, through which tin from future England was transported.

Economic Activity

During the period from about 1000 to 600 BCE, corresponding to most of the “Hallstatt civilization,” the economy remained close to subsistence level, except for the warrior aristocracy. However, this aristocracy likely held power over relatively small communities and governed small territories (five to ten kilometers around the center). Trade was mainly along an east-west axis, linking German mining areas that supplied copper and tin to western regions that used these minerals to manufacture bronze objects.

But from the beginning of the 6th century BCE, the foundation of Marseille by the Greek Phocaeans and the development of the Provençal hinterland led to the creation of a new north-south trade route of great importance. Numerous products of Greek, Marseillaise, or Etruscan origin, having traveled through the Rhône Valley and the Alpine passes, have been found in Gaul and in Northern and Western Europe: wine, gold and silver tableware, bronze and ivory objects, jewelry, weapons, and more. From the north, raw materials and semi-finished goods (wood, metals, resin, pitch, amber, salt, wool, hides) were sent south; the north also provided mercenaries and slaves.

These facts explain the decline of the Hallstatt civilization, but one must also consider the aggressive southward movement of the Celts of La Tène, who had preserved their warrior traditions. The slowdown in trade combined with several other factors: population pressure, worsening climatic conditions, and decreasing food resources.

Celtic Art and the Vix Grave

Four artistic styles are observed during the Hallstatt and La Tène periods. During the first civilization, Celtic art used geometric and abstract ornamental forms. The main source of inspiration was nature, specifically plants. Greek and Etruscan influences are evident, particularly in the use of Greek scrollwork, but there was no figuration. Art was mainly present on valuable objects: sword scabbards, jewelry, cups, etc.

The continuous vegetal style evolved from the first style and was no longer influenced by Mediterranean styles by the 4th century BCE. The use of two-dimensional vegetal motifs, less geometric in appearance, characterized this new style. Enameling and glassmaking developed. By the 3rd century BCE, the plastic style used geometric volumes to create figures through combinations. The sword style that developed alongside the plastic style used incised vegetal motifs, inspired by the vegetal style, to decorate, among other things, armament pieces.

The Tomb of Vix was discovered in 1953 in Burgundy near Mont Lassois, the site of one of the great princely residences of the Hallstatt civilization. Located at the heart of a large funerary complex composed of a dozen necropolises, the Vix tomb is the richest and demonstrates the care the Celts took in honoring their most illustrious dead.

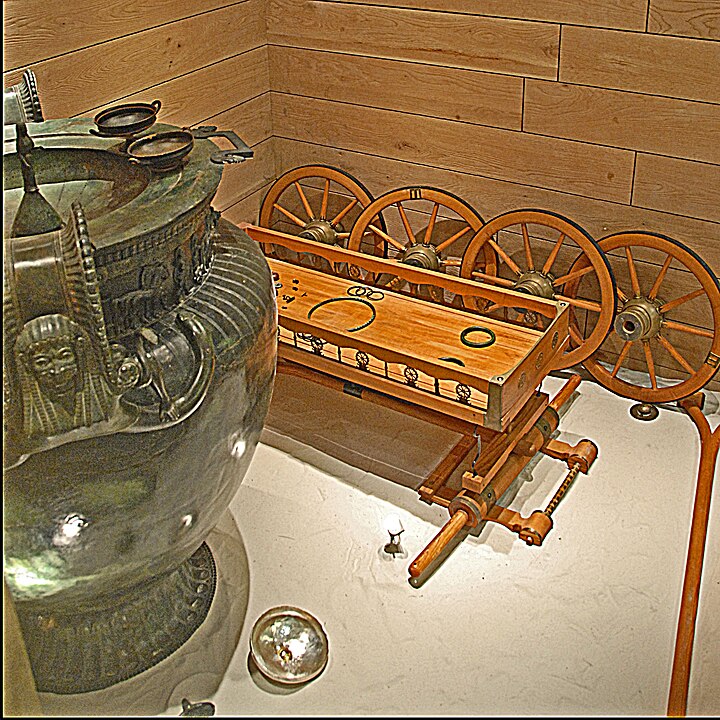

Dating from the 5th century BCE, this tomb, likely of a princess, reveals the wealth of the aristocracy that also controlled trade: the deceased wore a gold diadem, an amber bead necklace, a bronze torque, and bracelets. The funerary chamber also contained a disassembled chariot, a 1.65-meter-tall Greek bronze vase, and other bronze objects of Etruscan origin. These trade routes clearly connected the heart of Gaul with the Mediterranean world several centuries before the Roman conquest.

A Warrior Aristocracy

In Gaul, the Celtic nobility gained power through land ownership, mining, artisanal production, and trade. This social elite consisted of warrior leaders who excelled in cavalry skills. The lives of these Gauls were entirely devoted to war. When Caesar wrote about them, he called them equites (knights). From a young age, nobles received rigorous training and were highly attentive to their horses. They achieved a high level of cavalry skills thanks to the strength and speed of their mounts.

In battle, the men fought bare-chested and shouted to terrify their enemies. A good warrior was one who fought to the death. Fleeing or being captured by the enemy was forbidden and considered humiliating. By 100 BCE, however, dying in battle was no longer an obligation for warriors.

Religion of the Celts

Originally, the Celts worshiped the sun, mountains, forests, and rivers. They venerated as many deities as there were springs, fountains, forests, etc. Depending on the tribe, the Celts might worship the same god under various names or different gods altogether.

It is often believed that the Celts had a pantheon. Indeed, they created a series of gods that Julius Caesar compared to Roman deities. For instance, Taranis, the Gallic god of thunder and the sky, was assimilated to Jupiter. However, these deities did not form a unified group. They remained isolated and were often honored locally. Nevertheless, there were major deities common to all Celts, such as Taranis.

Other notable examples include Epona, the protective goddess of horses and riders; Cernunnos, the stag-horned god representing the renewal of nature’s forces; and Lug, a god associated with Mercury. Their attributes varied depending on the inspiration of the artists, reflecting a certain indifference to official religious norms. Moreover, the Gauls continued the worship of mother goddesses, a tradition dating back to the Neolithic period.

The Role of Druids and Bards

Celtic gods were honored through rites led by the druids. In this society, where everything was based on the sacred, druids held considerable influence. Due to the scarcity of written sources left by the Gauls, information about them remains fragmentary. Druids formed a privileged class and fulfilled a priestly role. The training to become a druid was open to all and could take up to twenty years. Education was conducted orally, through long poems recited or sung.

In addition to their religious functions, druids were interested in other studies, particularly astronomy, mathematics, and anatomy. They were also responsible for educating young nobles and taught philosophy and science. For instance, they developed a lunar calendar and units of measurement such as the league (a measure of length) and the arpent (an agricultural measure).

Druids were influential sages and advisors to kings. They acted as judges, with Celtic law being considered of divine origin. Every year, they gathered in the forest of the Carnutes to render justice. People with disputes would come to them and had to accept their rulings. For druids, nothing was more sacred than mistletoe from the oak tree. They harvested it once a year in November. The druidic sanctuary was a sacred grove made up of oaks.

Bards and vates (prophets) worked alongside the druids. The bards composed songs glorifying princes, while the vates prepared religious ceremonies and also acted as sacrificers and soothsayers.

After the 1st century BC, druids were threatened by Augustus, Tiberius, and Claudius, who condemned their barbarism, especially regarding human sacrifices. The political influence of druids during the Gallic Wars led the Romans to attempt to eradicate them. Gradually, they lost their political and judicial responsibilities.

Agriculture and Salt

Alongside the aristocracy and the druids was the common people, consisting of farmers, herders, and artisans. According to Caesar, society was unequal: “They [the people] are hardly treated differently from slaves, unable to take any initiative, not being consulted about anything. Most, overwhelmed by debt or crushed by taxes, or subjected to the vexations of the powerful, give themselves to nobles; these nobles have the same rights as masters over their slaves.” These statements seem extreme because by the time Caesar studied life in Gaul, aristocratic power had declined, and popular assemblies had emerged, mainly among the most powerful tribes (Bellovaci, Aedui, Nervii).

In the two centuries before the birth of Christ, Gaul was a true breadbasket. The rich and fertile land, combined with deforestation, allowed the Gauls to prosper on their territory. This is one reason Caesar conquered Gaul, as he needed to find sixty tons of grain per day to feed his army.

In Gaul, farmers grew cereals such as barley, millet, spelt, oats, rye, einkorn, and wheat, which was used to make bread. With barley, they brewed cervoise, the precursor to beer. They also cultivated cabbage, peas, onions, and garlic. Vine and olive cultivation spread in the southern region. The use of the plow equipped with an iron blade made plowing easier. Raising pigs, goats, sheep, poultry, and cattle was part of daily life.

Salt extraction was an important activity for the Gauls. Two techniques were used to collect it. Along the Atlantic coast, salt was harvested using containers called “augets,” thin clay sheets about 2 mm thick. Around 200 of these augets were placed on a hot furnace, allowing the exploitation of 20 liters of saltwater per day. The other method involved collecting seawater after high tides, which was mixed with freshwater. The resulting brine was poured into trays, and evaporation was forced to obtain salt.

Celtic Craftsmanship

The Celts were skilled artisans who mastered numerous techniques for working with raw materials. The discovery of iron, much more durable than bronze, allowed them to produce various tools. Initially reserved for weapons, iron was later used to make a wide range of everyday tools (hammers, nails, hinges, files, drills, sickles, knives, spoons, ladles, etc.).

Enameling, a Gallic specialty unknown to the Greeks and Romans, involved applying tinted glass paste to iron, either in flat areas or by pouring it into grooves made for that purpose. When heated, the paste became liquid, and the metal was heated to ensure both substances reached the same temperature. Once cooled, the piece was polished with a sandstone to highlight the enamel. This technique adorned brooches, torcs, bracelets, and sword scabbards.

Pottery initially served domestic needs, and potter’s wheels were used to make tableware. Over time, decorative elements like moldings and painted designs were introduced. Gallic potters also mastered the technique of reducing firing. Everyday pottery was gray or brownish and came in simple shapes.

The Gauls excelled in woodworking to the extent that some modern terms come from Gaulish words (such as “chariot” and “cart”). The Romans, impressed, either purchased Gaulish carts or imitated them. The Gauls produced a wide variety of wooden objects across many domains: chests, furniture, buckets, etc. The invention of barrels eventually replaced amphoras, which were less practical for transporting wine. Ash wood was used for wagon construction and tableware, oak for furniture and barrels, and yew for woodcraft.

Celtic Gaul: A Mosaic of Tribes

One thing is clear: Gaul did not possess political unity. It was composed of tribes ruled by local leaders and more powerful peoples led by a nobility. The most significant were the Aedui, Arverni, Bituriges, Carnutes, Sequani, Remi, Veneti, Pictones, Santones, Lemovices, Treveri, and Helvetii, all located in central Gaul. These groups formed states that united various civitas (city-states). From the 2nd century BCE onward, a civitas represented a people recognized by a common ethnic origin and varying territorial size. Each people was further divided into tribes, and within each tribe were families linked by a shared lineage. The size of a civitas varied from one group to another.

Until the 5th century, continental Celtic languages, including Gaulish, were spoken in Western Europe (Gaul, Hispania, and northern Italy), but their importance declined under the influence of Latin, and little is known about them today.

By the 2nd century BCE, the Celtic peoples ceased their migrations across different regions of Europe. In Gaul, they began to build their first cities, called oppida. Some cities emerged from the transformation or relocation of a village, while others were newly founded where no previous settlement existed. The founding and development of these settlements are generally attributed to two events: the invasion of Gaul by the Cimbri and Teutons at the end of the 2nd century BCE, and the creation of the Roman province of Narbonensis. The first event increased the need for protection, while the second allowed the Gauls to observe Roman cities and replicate them. Today, through extensive archaeological excavations, we know that the creation and development of these cities reflected significant changes in Gaulish society.

The Romans Enter Gaul

The Romans entered the scene as early as 125 BCE, helping Marseille defend itself against a coalition of Gauls and Ligurians. The following year, the consul Sextius Calvinus captured Entremont and founded the Roman colony of Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) nearby. Two years later, the Roman army defeated the Allobroges, the most powerful Gaulish people on the left bank of the Rhône.

The Arverni, who came to assist the Allobroges, were also defeated, and the Romans annexed new territory, including the Rhône valley up to Vienne and Geneva, the entire southern slope of the Cévennes up to the Tarn, and westward to the Garonne valley near Agen. This led to the creation of the first Roman province in Gaul, Provincia, in 120 BCE. From that moment, numerous trade relations were established between the Romans and the Gauls.

Roman interference in Gaul became increasingly intense, culminating in Julius Caesar’s decision to conquer it in 58 BCE. Caught between the Romans and the Germanic peoples, the Celtic world gradually disappeared, with its language surviving only on the Atlantic fringes of Europe, in the British Isles (Wales, Scotland, Ireland) and in Brittany.