Terrible Hairstyles

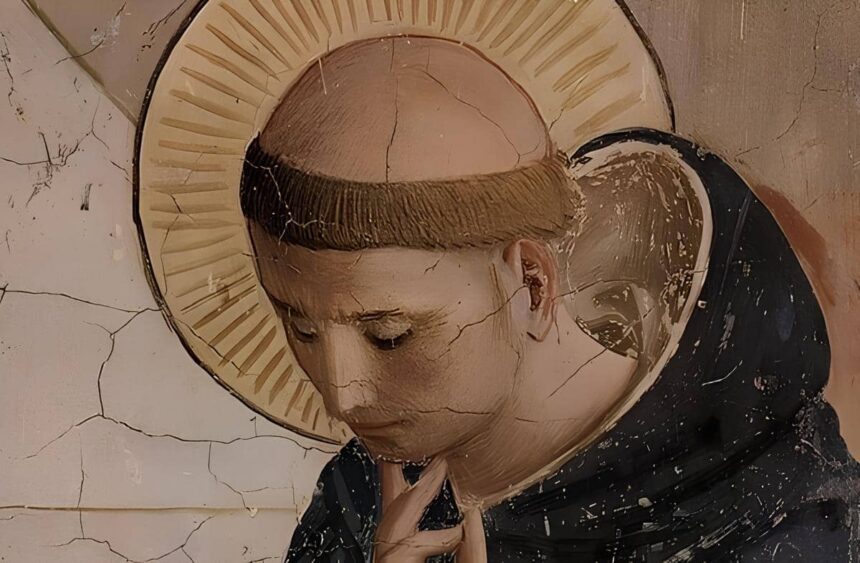

In historical films and series, you’ve probably noticed the rather extravagant haircuts of medieval Catholic monks. The top of their heads was shaved, with a ring of hair around it. This was called a “tonsure.”

The expression “to take the tonsure” comes from the practice of shaving this part of the head.

It’s unclear when monks began this tradition, but it’s evidently ancient, possibly dating back to the 2nd, 3rd, or perhaps the 5th century AD. Historian Daniel McCarthy believes the tonsure originally symbolized the crown of thorns worn by Christ.

Another theory is that the hairstyle was chosen by the clergy due to the Roman Empire’s custom of shaving the heads of slaves. Monks referred to themselves as “slaves of Christ.” Alternatively, the tonsure might have been linked to a commandment in the Torah forbidding shaving the sides of the head—a rule that could have subtly transitioned from Judaism to Christianity.

Regardless of its origin, monks wore the tonsure for about 1,500 years, and it wasn’t until 1972 that Pope Paul VI declared it unnecessary. His reasons were twofold. First, it was a “meaningless ceremony,” and second, having to walk around with a shaved crown discouraged some who were overly attached to their hair from dedicating themselves to God.

Ergonomic Issues

Monks were always busy with various tasks, but their most demanding job was copying books. The printing press hadn’t been invented yet, so until the 13th century, manuscripts had to be copied by hand.

This work took place in special rooms in monasteries called scriptoriums. However, the conditions were far from ideal. Initially, monks copied books by dictation, holding the manuscripts on their laps because tables weren’t introduced until the 7th century.

Only in the most prestigious monasteries, like St. Gall Abbey, were there spacious, well-lit scriptoriums with comfortable workstations, a lectern for the abbot to dictate from, and large windows for natural light.

Most monks had to make do with gloomy cells, working alone for years.

For example, Eadfrith, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, wrote the Lindisfarne Gospels in solitude in a shack on St. Cuthbert’s Island, using seashells as inkwells.

Scribes often had to lick their brushes to keep them sharp, resulting in fragments of paint getting stuck in their teeth.

It’s no wonder monks grumbled about their tough life. The books they copied were often filled with marginalia—notes and drawings in the margins.

These texts were full of complaints from tired monks: “Oh, my hand hurts so much!” “I’m so cold, my fingers are trembling with chill,” “When will I finally finish this chapter?” “Thank goodness it’s almost night, and I can rest.”

“Those who don’t know how to write think it’s easy work, but although these fingers hold only a quill, the whole body grows weary.”

Ferreol, Bishop of Uzès

There are also more poetic marginalia. For instance: “Writing is incredibly tedious. It bends your back, dims your sight, and twists your stomach and sides.” Or: “As a sailor rejoices in reaching harbor, so does a scribe rejoice at the last line.”

At the end of their work, a scribe might jot down something like, “Finally, I’ve written it all: for Christ’s sake, pour me a drink,” or even, “My right hand has recovered from the pain. If only a beautiful maiden were given to scribes as a reward!”

Cats, Demons, and Other Distractions

As you might imagine, it was easy to make mistakes in such conditions. Writing in the margins was one thing—it was allowed. But making errors in the text was quite another. Every correctly written letter atoned for a sin, while every mistake added to it.

Abbots intimidated their scribes, warning them that any error brought them closer to a life sentence in hell. The scribes excused themselves by saying demons interfered with their work.

Medieval monk-scribes believed in a special demon named Titivillus. As theologian John of Galensis wrote in 1285, Titivillus observed scribes and “collected into his sack a thousand errors made by monks every day.”

This demon collected mistakes, errors, corrections, and even poorly recited Psalms. From these “stolen from God” fragments, the malicious demon compiled accusations against Church members, which he would present at the Last Judgment, condemning the negligent monks to eternal damnation. Naturally, the monks were deeply anxious about this.

Besides demons, physical creatures also caused distractions. For example, a cat walked across a medieval manuscript at the Dubrovnik State Archives after stepping in an inkwell. A bird accidentally flying into the scriptorium could also leave its four-toed imprint on a precious folio.

Book production was so laborious that it usually took a scribe a year to produce a standard Bible. You can imagine how monks felt when their work was damaged by a cat’s antics.

Exorcism Difficulties

And now, back to demons. In the Middle Ages, demons were believed to be the cause of many misfortunes. So, when someone began having seizures, cursing, fighting, or showing other signs of demonic possession, priests—not doctors—were called for help. The priests would then battle the demonic entity.

The most common methods of exorcism were the cross, holy water, prayer, and, less often, the laying on of hands. These usually sufficed, but sometimes the devil resisted, and the clergy resorted to more extreme measures.

The afflicted might be severely beaten or even drowned in cold water—for their own good, of course.

Naturally, the unfortunate soul didn’t feel anything because the demon controlled the body. The idea was that inflicting pain on the devil would cause him to flee the tormented body. The beatings were accompanied by insults, as demons were prideful creatures and could not endure rudeness.

Sometimes, though, violence didn’t help. For instance, St. Norbert of Xanten beat a possessed man with a whip, but the demon refused to leave—apparently, he was used to it. He only cried out, “Your whip doesn’t hurt me, your threats don’t scare me, death doesn’t torment me!” What could be done with such a case was unclear. Fortunately, sprinkling the poor man with consecrated salt eventually worked.

At times, demons would slip up, practically doing the exorcist’s job for them. In a 12th-century treatise, a case is described where monks were fighting a demon possessing someone, but it wouldn’t leave and mocked them. The exorcists were desperate when the demon blurted out, “You’re wasting your time. Only Erminold can expel me, and even then, it’s doubtful.”

The monks searched for someone named Erminold, found a saint by that name, and brought him to the demon. The latter confirmed: “Yes, that’s the one I was talking about.” A bit naive for a servant of hell, wouldn’t you say?

Finally, some devilish creatures would only leave the possessed if they were offered a relic, such as a hair from a saint’s beard.

Naturally, finding such a rare item was often a challenge. But sometimes, they were lucky.

In a 12th-century report by a monk from Soissons, one particularly stubborn demon demanded nothing less than the tooth of Christ the Savior before he would agree to be exorcised.

They searched for the tooth and couldn’t find it. They had to ask the demon again, and it explained that the relic was in the Church of St. Medard. They sent someone there, retrieved the item, and the demon, after some time, finally left the possessed.

But more than demons, monks were irritated by imposters who faked possession just to get attention or avoid punishment for their crimes, as the responsibility was then placed on the demon.

These frauds were easy to spot: as soon as they were doused with holy water and whipped as expected, they immediately stopped their antics. Thomas of Celano described how one day St. Francis began an exorcism, and the possessed person instantly recovered. The exorcist immediately realized it was a fraud and, “feeling deceived, quickly left the town in shame.”

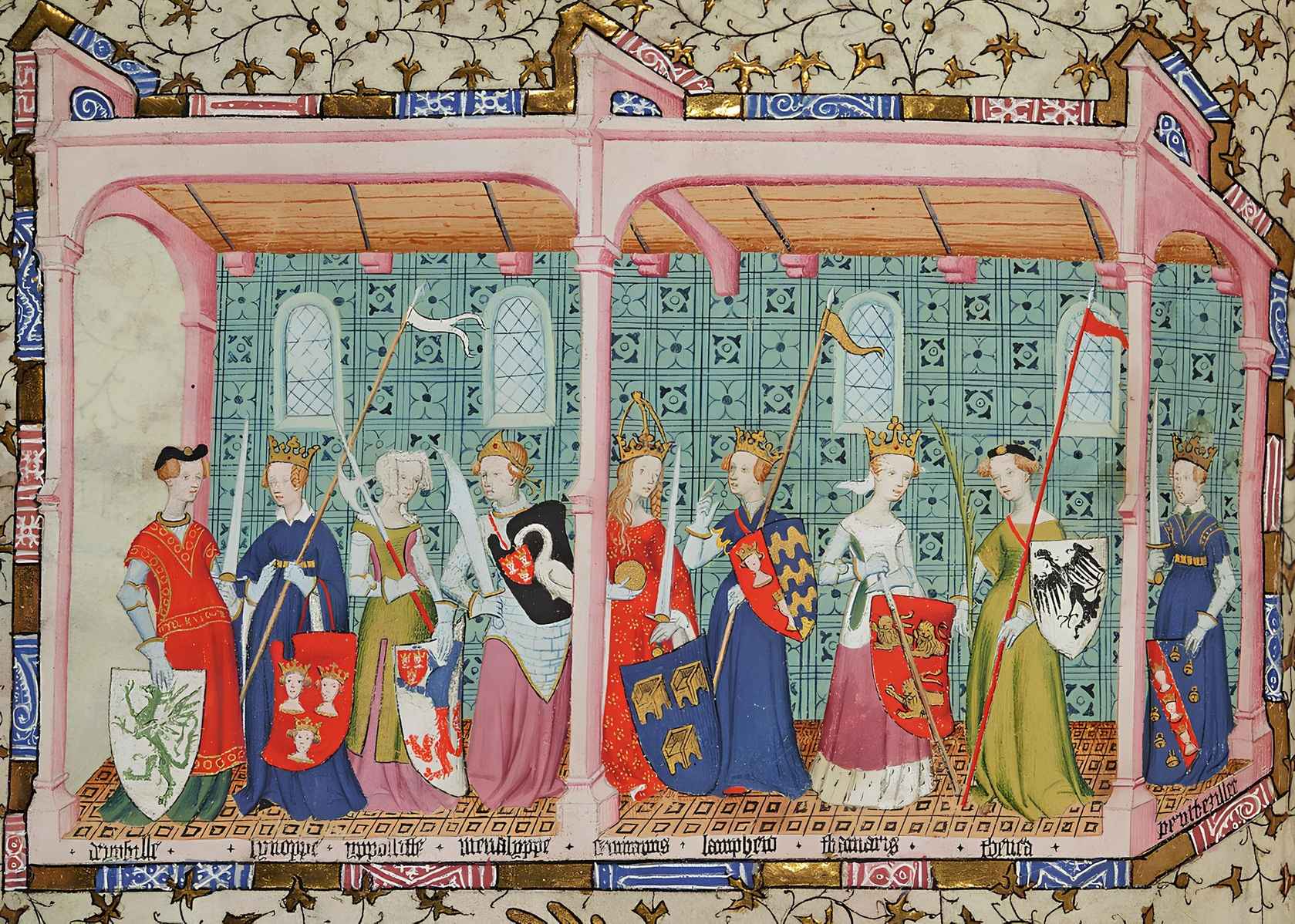

Vikings and Knights Raiding Monasteries

The most frequent attackers of medieval monasteries were the wild Vikings, so often that the monks had a special prayer for protection from the northerners: “Our Holy Lord, protect us from the savage people of the Norwegians.”

There is another version circulating online: “Save us, God, from the Norman sword! Save us, God, from the Magyar arrow!”, but researchers D’Hanen and Magnusson believe this to be a modern invention with no medieval origin.

Unsurprisingly, many monasteries fortified themselves like true fortresses.

However, it wasn’t just Vikings who looted abbeys and enslaved their inhabitants. Fellow knights, who were supposed to protect monks, often did the same.

For example, once John FitzAlan, the first Baron Arundel, was marching with his troops to aid the Duke of Brittany. However, a strong wind struck, and the soldiers decided to wait out the storm in a nearby monastery in Southampton.

Unfortunately, this monastery happened to be a convent. The knights couldn’t resist: they looted everything valuable and took the nuns with them as concubines.

Fortunately, the abbess managed to excommunicate the baron from the church. As Arundel tried to cross the English Channel, 25 of his ships were wrecked by a storm. He ordered the captives to be thrown overboard to lighten the ship, but it didn’t help. The knight, along with his squires and most of his troops, drowned.

Other Monks

It wasn’t just Vikings or rogue knights who robbed monks. Sometimes their superiors did too. In 1190, Bishop Hugh of Lincoln visited the abbey in Fécamp to venerate the relics there. Flattered by his attention, the monks showed him their greatest treasure—the hand of Mary Magdalene.

Without hesitation, Hugh bit off a piece of the relic in front of the shocked monks, justifying it by saying, “We receive the body and blood of Christ with our teeth in the Eucharist.”

In the end, Hugh was canonized because he was truly a holy man.

As mentioned earlier, books were extremely valuable at the time—one could easily be worth as much as a decent house. Many monasteries survived by selling copied manuscripts.

However, they had to lend books to their peers and superiors for free, often for long periods—a year, five years, or even ten or twenty years. Sometimes, the books were simply never returned.

There’s a record of an abbot borrowing a manuscript from a neighboring monastery, only for it to disappear. The priest explained his reluctance to return it by saying, “The book is so large that it cannot be hidden in a sleeve or bag… Evil people would inevitably be attracted to its beauty.”

How the abbot managed to remove the manuscript in the first place remains unclear, but he couldn’t bring it back.

Kissing the Floor and Other Practices

Many monastic orders, especially the Benedictines, believed that the mere thought of sin was enough to commit it. Therefore, one must start repenting immediately.

Thus, whenever young novices saw the abbot frown, they would instantly throw themselves at his feet. Much like in the movie The Sound of Music, where the main character Maria kissed the floor in front of Sister Bertha to save them both time without waiting for orders.

However, the floor was not the most unpleasant thing the monks had to kiss.

When travelers visited the monastery, monks were required to greet them “with heads bowed or lying prostrate on the ground.” They would wash the guests’ hands and feet, greet them with brotherly kisses on the lips, and share their meals.

However, Saint Benedict recommended doing this only after a joint prayer to avoid “the devil’s tricks,” ensuring that the visitors could be trusted. After all, they might be Vikings.

Finally, on Maundy Thursday during Holy Week, monks would bring the poor from surrounding villages into the monastery and humbly wash and kiss their feet.

Digestive Problems

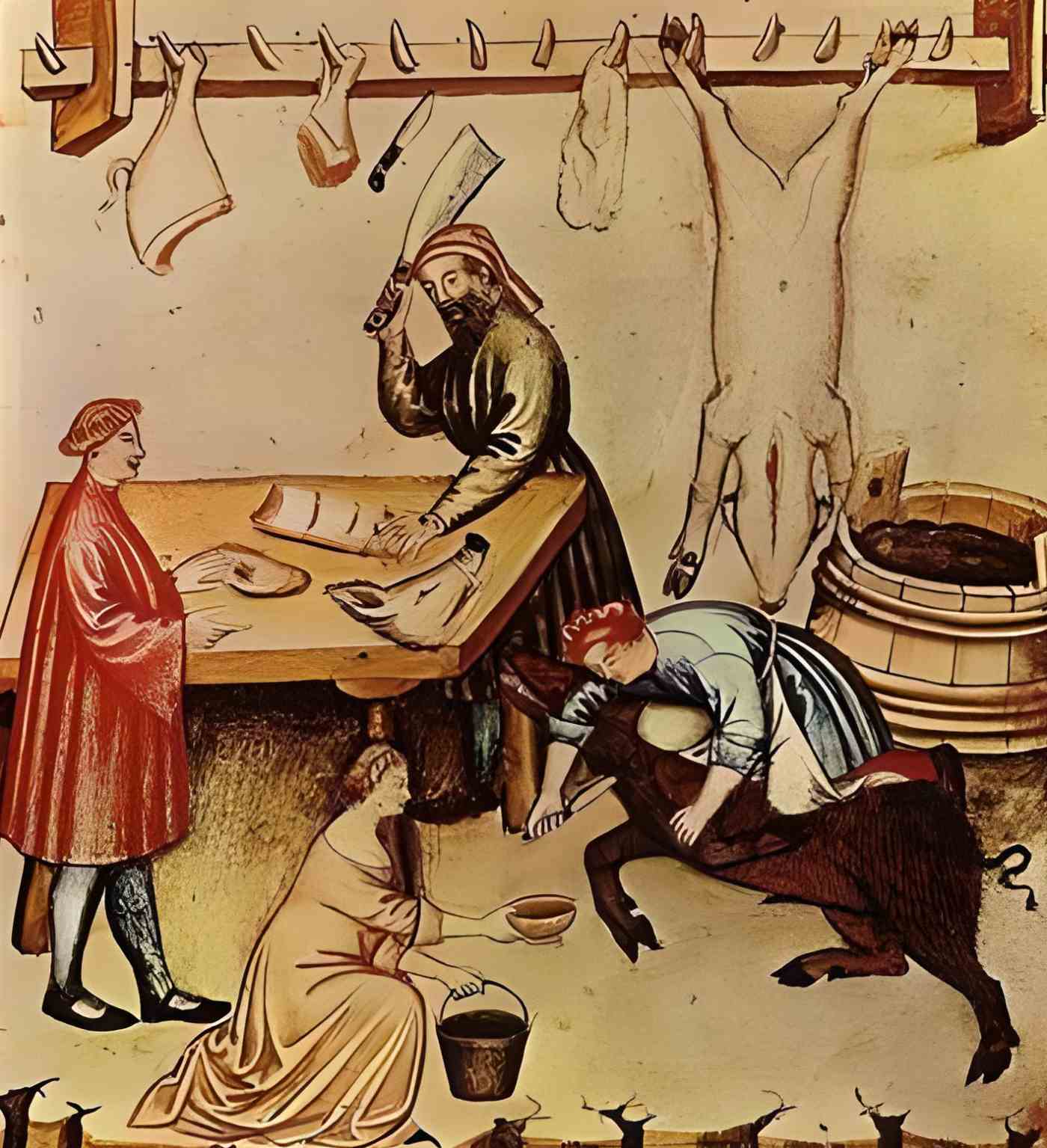

The diet in monasteries varied according to their rules, but in general, medieval monks were not overly concerned with healthy eating.

Their standard diet consisted of sourdough white bread, ale seasoned with herbs, and eels. Eels were highly valued because they could be eaten during fasting, and unlike meat, they were thought not to incite lust.

In fact, peasants even paid rent with eels until the 16th century, and an annual turnover of 540,000 eels is recorded in the *Domesday Book*.

Another favorite was beaver tail, which was considered a fish due to its scaly appearance. The rest of the beaver had to be discarded or sold to perfumers for musk.

Coastal monasteries shamelessly hunted dolphins as well. Science had not yet discovered that they were mammals.

However, in 1336, Pope Benedict XII decreed that while mortifying the flesh during fasting was good, it was fine to indulge outside of fasting periods. He permitted the consumption of “all four-legged animals.”

As a result, monks began to eat lamb, beef, pork, venison, rabbits, hares, chicken, and various game alongside bread, fish, seafood, grains, vegetables, fruits, eggs, cheese, wine, and ale.

At that time, they had not yet invented eating small meals frequently, and there was no time left for prayer, so meals were rare but abundant. Typically, they ate once a day in winter and twice in summer.

This unbalanced and calorie-rich diet led to widespread digestive problems, sometimes quite serious. For example, in Muchelney Abbey in Somerset, they had to build a separate two-story building—a latrine for forty people—to accommodate all the sufferers.

Additionally, monks collected various remedies to help themselves and their brethren. In Muchelney, a laxative recipe using different fruit extracts has survived. There were also suggestions like, “Take a small piece of soap, press it, and insert it rectally, then lie down on the bed.”

Monasteries even had a special position—the circator—a person who patrolled the monastery at night to ensure order and make sure the novices were not engaging in ungodly activities. One of his unofficial duties was to discreetly wake monks who had fallen asleep in the latrine.

“God’s Pearls”

There is a common misconception on the internet that people in the Middle Ages did not wash at all. This is not true.

Of course, regular baths were only taken by the nobility, who could afford to pay for fuel to heat water—after all, swimming in freezing well water wasn’t exactly an option. However, even commoners almost universally washed their hands and faces in the morning.

Monks had varying hygiene practices depending on the specific rules of their monasteries.

In many wealthy abbeys with less strict regulations, there were large lavatories—rooms with running water. Before meals, monks were required to wash their hands. These rooms also had sharpening stones because the men of God (like everyone in the Middle Ages) always carried knives with them. These knives replaced all other eating utensils—forks were not in use then. Towels were changed twice a week in the bathhouses.

However, in other monasteries, washing was much rarer. For example, it is known that monks at Westminster Abbey were required to take a bath four times a year: at Christmas, Easter, the end of June, and the end of September.

Some especially devout brothers neglected washing altogether, believing that by doing so, they mortified their flesh and thus aided the salvation of their immortal souls. They also thought this helped resist devilish lust and idleness and allowed them to imitate the holy saints.

As a result, many medieval doctors, including John Gaddesden and Bernard Gordon, noted the clergy’s susceptibility to parasites.

The aroma coming from an unwashed ascetic was called the “odor of sanctity,” and lice were referred to as “God’s pearls.”

Even famous individuals, such as Bishop Thomas de Cantilupe of Hereford, Dominican theologian Henry Suso, or Archbishop Thomas Becket of Canterbury, suffered from these parasites. According to contemporaries, lice swarmed on Becket’s woolen clothing both inside and out, and Cantilupe had them “removed by the handful.”

Women were no better off, which was reflected in the literature of the time. In the 12th-century poem *Planctus Monialis*, a young nun pleads with a young man to love her and complains about her hardships in the convent: “My shirt is dirty, my underwear is not fresh, made of coarse threads… my delicate hair smells of filth, and I endure lice that scratch my skin.”

However, the steadfast faithful did not complain, as parasites were considered a form of martyrdom.