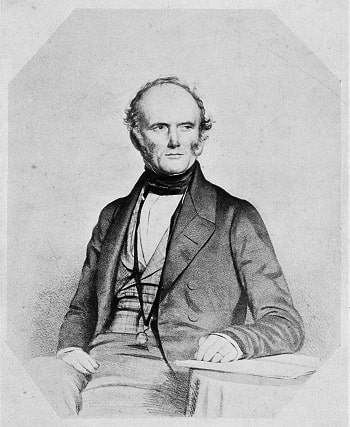

Today, Charles Lyell is best known because of the geologist Charles Darwin, who read his books as a child during his famous voyage with Beagle and used them to guide his studies on the theory of evolution. Charles Lyell is one of the pioneers of the development of geology, but he is also an important personality on his own.

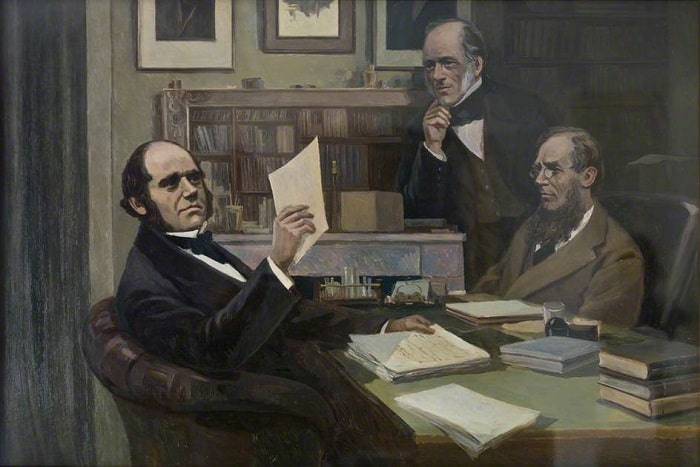

His most important work, Principles of Geology, was first printed in three volumes between 1830 and 1833, but he continued to revise it until his death. Most of these revisions were the result of an ongoing dialogue with other geologists, who appreciated and adopted certain parts of his work but also strongly criticized some aspects. In some important respects, the Earth sciences have emerged as a result of this fruitful interaction.

Who was Charles Lyell?

Charles Lyell was from a senior family of Scottish landowners but grew up in the south of England and remained a Londoner throughout his adult life; he went to the family home on the shores of Northern Scotland only on holidays. After his student years in Oxford, he completed her law internship in London; he acted as a deputy for a short period until it turned out that he could earn a decent income from authorship.

He married Mary Horner, the highly educated daughter of Leonard Horner, the chancellor of University College London; they had no children. During a visit from his young friend Darwin, he found Lyell neglecting his wife while passionately talking about geology. He wrote to his fiancé with sarcasm that he wanted to practice neglect. His wife, who worked as a research assistant at home and on extensive trips in Europe and later in the United States, was invaluable to Lyell.

He was a liberal constitutionalist in British politics but culturally cosmopolitan; the French language was accepted as the language of science and culture at that time, and she was fluent and felt at home next to the intellectuals of all nations. He was raised in the Anglican faith, but she decided to go to the Unitarian Church in London when he was grown.

To rebuild the hidden history of the globe

Charles Lyell united two opposite intellectual facts that shaped the earth sciences before him. He embraced the first one when he attended the classes of charismatic geology professor William Buckland when he was a student at Oxford. Buckland adopted the approach advocated by the great Parisian zoologist, Georges Cuvier. Cuvier called on geologists to “remove the limits of time.” He called on geologists not to expand the time scale, which has long been considered far beyond the imagination of man, but to rebuild this long history with reliable details.

Similar to historians’ use of documents to reconstruct human history, geologists had to find fossils and other traces of the long past. Lyell, like his teacher Buckland, adopted Cuvier’s approach as the correct principle for his chosen discipline; geologists should have been the earth’s historians, reconstructing the earth’s history from any traces of the past that have reached us today.

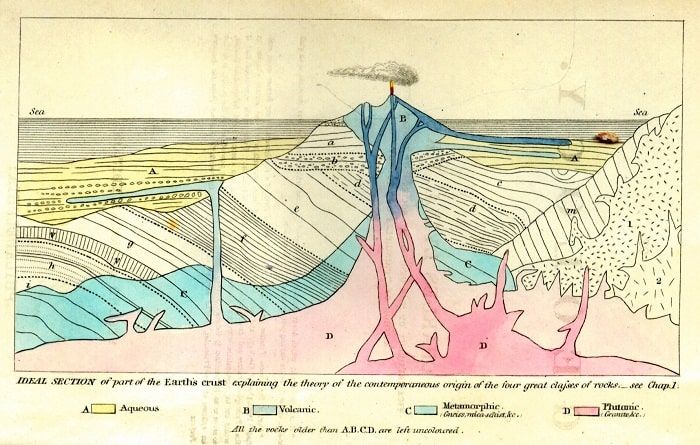

However, Lyell was deeply influenced by James Hutton‘s geology model, which sees the earth as unchanged and therefore a mass governed by ahistorical laws. Hutton previously portrayed the earth as a physical system that maintained a continuous dynamic balance, similar to the Solar System of planets orbiting the Sun. Mathematician and astronomer John Playfair made this model available to Lyell’s generation. Thanks to Playfair, Lyell focused his attention on what would later be known as “modern causes.”

The modern causes

According to the theory, there are geological processes that can be directly observed today, such as volcanoes, earthquakes, erosion, and sedimentation, and that can be used to interpret the traces of activities in unobservable pre-human history. Other geologists had already said “the present is the key to the past,” but Charles Lyell was convinced that modern causes were appropriate for describing all but some of the traces of the distant past. He said that it wasn’t necessary to think that there had never been a disaster like this before.

At the center of the geological discussions was a disaster assumption of this magnitude. Maybe Buckland and many other geologists were at the dawn of human history, but at a very late time in the history of the earth, in many places, they saw the physical traces of what they call the “geological flood,” which was envisioned as a mega-tsunami and hit most of the world, if not all of it. Buckland used it to identify “Noah’s Flood” very early in the history of written humanity, thereby confirming the historical validity of the Bible and, in particular, ensuring the acceptance of newly established geology science in Oxford.

Buckland and many other geologists were seeing the physical traces of what they call the “global deluge” or “flood geology,” imagined as a mega-tsunami that struck most of Europe, if not all of Earth, at the dawn of human history but also extremely late in Earth history.

Lyell was not a fan of the Church of England’s cultural sovereignty, so he fought against it. He said that all the evidence of very early disasters on Earth that were similar to the flood in question could be explained by normal processes.

Reading the fossil records

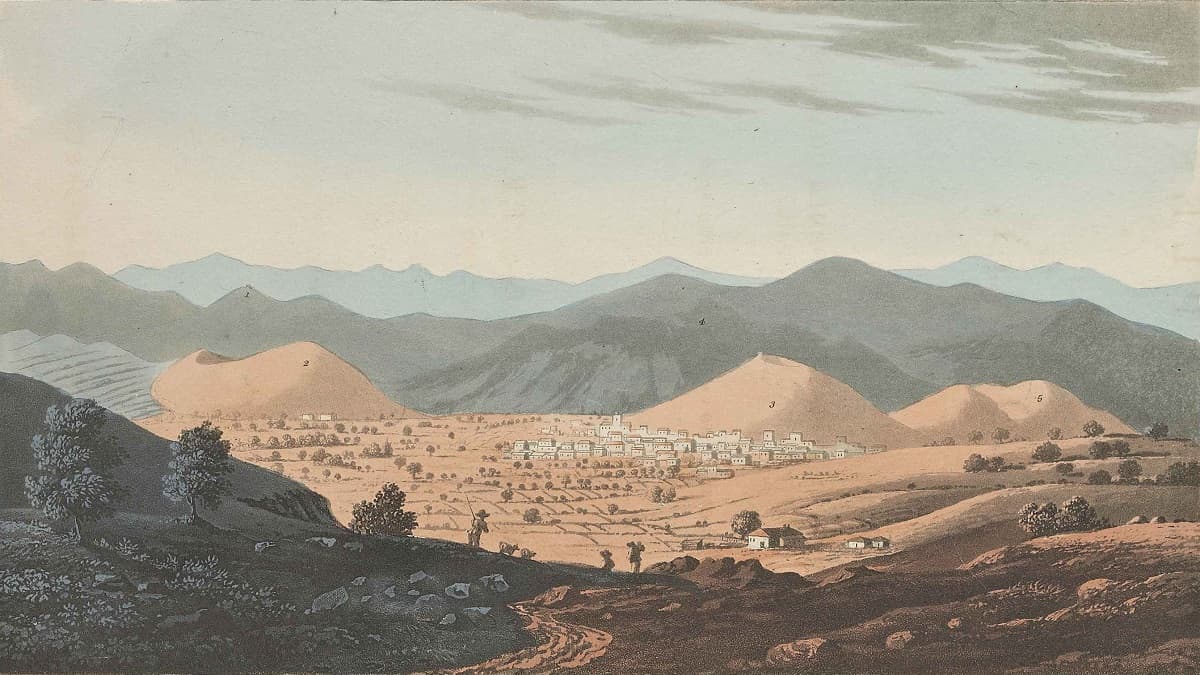

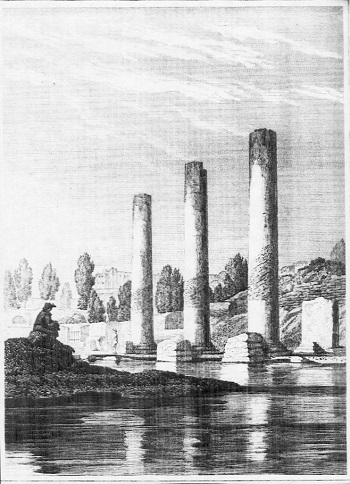

The confidence that Lyell nurtured in the explanatory power of these modern causes was strengthened with extensive trips to France and Italy in 1828–1829. He saw with his own eyes the magnitude of the effects of volcanoes such as Etna and Vezuv. Field studies revealed that throughout human history, the earth’s crust was at least as dynamic as the planet’s early history. He found a new chain of evidence in Sicily that connects human history with geological history and gives an idea of the size of the Earth.

Other geologists (including many who considered themselves religious) said they had already accepted it. But Charles Lyell believed that they could not accept it in practice. According to him, the assumption that any disaster was extraordinary was made unnecessary by correctly understanding the power of modern causes and by realizing the length of time these forces were in effect. He suggested that all the evidence presented was Earth’s slow and imposing cycles of change. These were events that did not follow a prominent direction in the long term and were in dynamic balance.

When he returned to England, Lyell used the persuasive language that he had acquired in his short career as a lawyer to reinterpret Buckland-style geology in Hutton’s terms in his comprehensive Principles of Geology work. The readers of the book in Britain were particularly impressed by the reconstruction of the highly expanded, immense history of the globe by Lyell because it contradicted the commonly held beliefs in the scriptures. In the rest of Europe, people were starting to learn about the ways that scholars interpreted the Bible. The magnitude of the Earth’s time scale had been inured for a long time, and Lyell’s approach did not seem so unusual.

Oldest rocks

Charles Lyell devoted much of his work to what he called “the alphabet and grammar of geology.” Lyell enriched his observations with numerous printed sources and first-hand reports to demonstrate the impact of modern causes, which would result in enormous effects when given enough time, such as the rise of new mountain ranges. All of these were sincerely embraced by other geologists, who increasingly embraced Lyell’s emphasis on modern causes in their work. However, they also questioned whether all traces of the past could be explained in this way.

However, there were no satisfactory scientific answers to some events in the Holy Book. For example, flood geology could have caused such a shock and disaster only with the “extraordinary” intensity of ordinary processes. Their avoidant approach was justified for a short time. In the 1840s, the great flood hypothesis was replaced by a geologically recent ice age interpretation. Buckland was one of the first to adopt this new idea, while Lyell was reluctant to accept the reality of such a major disaster.

In the last volume of The Principles of Geology, Lyell used the “alphabet and grammar” of geology to decipher the traces of the Earth’s past and reconstruct the nearest periods that are very similar to the world today. He argued that the oldest rocks had undergone a major change in the depths of the Earth as a result of their “transformation” processes, so they could not provide any evidence of the origin of the planet. As Hutton had long suggested, he came to the conclusion that the Earth is, in fact, a system that is in a constant state of slow, steady change.

Charles Lyell, Hutton, and Darwin

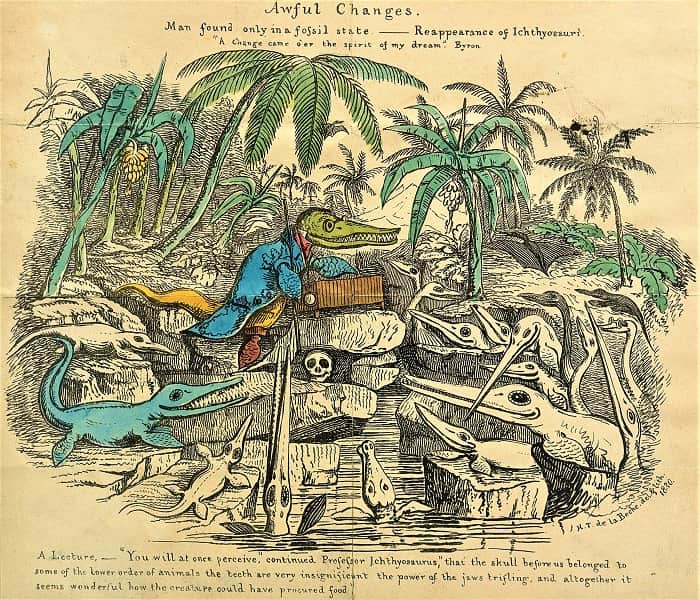

The Huttonian Earth Model approach brought by Lyell was criticized violently by geologists for its inconvenience when compared to modern causes; it was this approach, not modern causes, that would later be called “pro-uniformity.” Lyell was now the only example of a uniformitarian geologist. Above all, other geologists pointed to increasingly clear evidence in the fossil record that there was a certain direction in the history of life on Earth. The most striking evidence was the appearance of fish, then reptiles, later mammals, and eventually humans among vertebrates.

Of course, Lyell was aware of all this, but not necessarily convincingly. He had to explain it with the disorder in the fossil record. He associated the cyclical structure of the physical phases of the Earth with similar events in the history of life. As a result, geologists have found that Lyell’s theorizing method is far from reliable.

Charles Lyell had been very helpful in creating a productive synthesis between the highly historical model of geological science referred to by Buckland and Hutton and its highly physical model. It turned out that the Earth had an uncertain and unexpected history, just like human history. But at the same time, all these events could be attributed to non-historical geological processes based on the immutable laws of nature. Lyell’s student, Darwin, who would first introduce himself as a geologist, had effectively transferred this synthesis to biology. But Charles Lyell’s success deserves to be recognized on its own, as the methods of reasoning used on Earth are still the basis of modern geology today.

Bibliography:

- Smalley, Ian; Gaudenyi, Tivadar; Jovanovic, Mladen (2015). “Charles Lyell and the loess deposits of the Rhine valley”. Quaternary International. 372: 45–50. Bibcode:2015QuInt.372…45S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.08.047. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Stafford, Robert A. (1989). Scientist of Empire. Cambridge: University Press.

- Taub, Liba (1993). “Evolutionary Ideas and “Empirical” Methods: The Analogy Between Language and Species in the Works of Lyell and Schleicher“. British Journal for the History of Science. 26: 171–193. doi:10.1017/s0007087400030740. S2CID 144553417.

- Thanukos, Anna (2012). “Uniformitarianism: Charles Lyell”. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 23 July 2012.