The Icelandic Christmas celebration, known as Jól, combines traditional folklore and religious practices. The celebrations begin four weeks before Christmas Day, on Epiphany, and last thirteen days. The 13 Yule Lads, an Icelandic version of Santa Claus, put modest presents in the shoes of youngsters placed by the window. As a means to commemorate ancestors, Icelandic homes are decorated with Advent lights, while cemeteries and gravestones are also ornamented. A non-alcoholic concoction of Maltöl and Appelsín, a regional orange soda, is a traditional Christmas drink in this country. Elves, Yule Lads, and Icelanders say goodbye to one another with dances and bonfires that round off the holiday season until next Christmas.

The Name for “Christmas” in Icelandic

The Icelandic word for “Christmas” is “jól.” An old pagan festival commemorating the winter solstice is linked with this word, which is also present in Old Norse. Possible connections to words in other Germanic languages suggest that this word may have originated from a reconstructed Germanic form *jew-la-ja, meaning “the period when the sun moves.” However, the exact origin of the word is unknown. “Gleðileg jól!” is the default Christmas greeting in Iceland for “Merry Christmas”.

The Past of Christmas in Iceland

Christian Christmas festivities eventually absorbed the old winter solstice rituals in the history of Iceland. Puritan laws in the 16th century had an impact on Christmas customs in the country, much as they had in the United Kingdom and the United States.

The islanders’ primary industry during the Advent season shifted to woolen products, which were eventually traded for Christmas presents in the years that followed. Icelanders would use sticks (“toothpick”) to keep their workers awake during the “stick week” leading up to Christmas.

Faith-Based Christmas Practices

In Iceland, it is customary to pay respects at the graves of ancestors who have passed away on the morning of Christmas Eve (Aðfangadagur in Icelandic), which is December 24th. Also, on December 24th, church bells in Iceland traditionally sound at 6 o’clock.

Well-Known Icelandic Customs

Icelandic Christmas Tree

The Icelandic Christmas tree has been a part of the country’s celebrations since 1863. It was originally intended to utilize mountain ash trees instead of fir trees since there are no naturally occurring evergreens in this nation. Roughly eighty-five percent of Icelanders still put up a Christmas tree.

Along with that, from 1951 until 2013, the city of Oslo generously lit a big Christmas tree in Reykjavík. Because of the exorbitant expenses of shipping, this practice was stopped. The big tree that is lit up every year in the capital of Iceland is still called the “Oslo Christmas Tree” in honor of the longstanding tradition and goodwill between the two nations.

In remembrance of an Icelandic fisherman who fed the people of the Hanseatic metropolis during the terrible famine of 1946–1947, the German city of Hamburg also annually sends a Christmas tree to the capital of Iceland as a token of appreciation.

On the first Sunday of Advent, this tree is illuminated.

Icelandic Advent Wreath

While records of the Advent wreath practice in Iceland date back to the 1930s, it wasn’t until the ’60s and ’70s that it really took off.

Jólabókaflóð: Christmas Book Flood

Jólabókaflóð, which means “Christmas book flood” in English, is a common practice in Iceland that involves giving books as Christmas presents. This practice first started when paper was one of the few commodities exempt from import restrictions during WWII. Every year around November, Icelandic publishers send the Bókatíðindi, a catalog of books set to be published in December, to every household in the nation, adding to this tradition.

Holiday Card Customs

Sending Christmas cards is a rooted tradition in Iceland; however, these days, virtually half of Icelanders reportedly send their holiday greetings via email. One might still come across Christmas cards with puffins, a bird that represents Iceland or cards that showcase the Reykjavik skyline or Hallgrímskirkja cathedral.

Grýla, Leppalúði, the Jólasveinar, and the Yule Cat

Grýla, the female monster that is said to be always hungry, and her husband Leppalúði live at Bláfjöll (“Blue Mountain”), close to Reykjavík, according to the traditional story. She reappears around Christmastime in search of mischievous kids to kidnap.

The thirteen elves known as the Jólasveinar (the “Christmas boys”) are the progeny of Grýla and Leppalúði. Their names range from Stekkjarstaur and Giljagaur to Stúfur, Þvörusleikir, Pottaskefill, Askasleikir, Hurðaskellir, Skyrgámur, Bjúgnakraekir, Gluggagægir, Gáttaþefur, Ketkrókur, and Kertasníkir. During the thirteen days between Christmas and Epiphany, beginning on December 12, the eve of Santa Lucia, they come down from the mountain each night to steal food or play tricks on children before going back home, one by one.

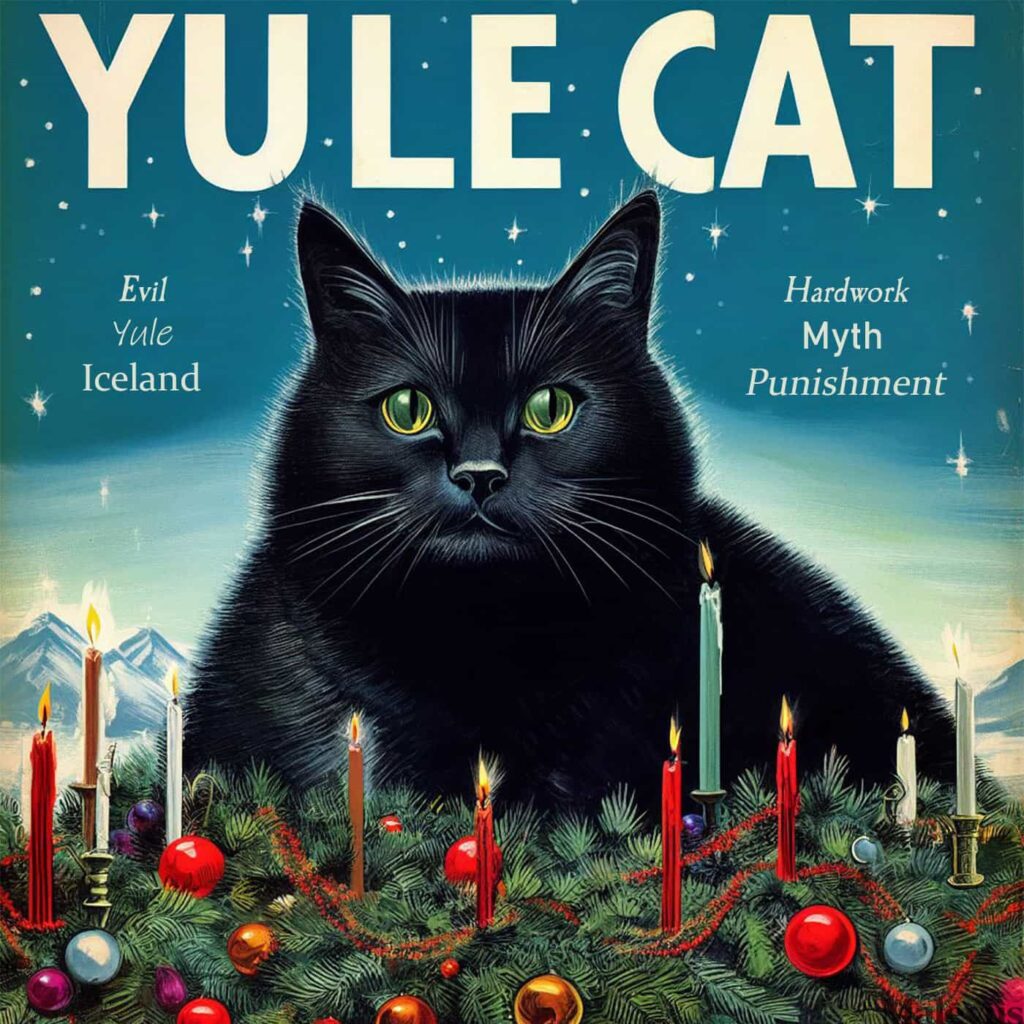

Grýla and Leppalúði also have a scary domestic animal called the Christmas Cat or Yule Cat, which is said to abduct and eat anyone—children or adults alike—on Christmas night if they aren’t wearing or haven’t gotten a new outfit. It seems that this myth was spread to inspire hard work in the spinning and weaving of wool and yarn.

The Icelandic government issued an order in 1746 outlawing the spreading of terrifying Yule Lad tales to youngsters, which contributed to the gradual meliorism of these entities and their eventual incorporation into Santa Claus. So, the Jólasveinar have become gift carriers, and kids put out a shoe to see if Santa would fill it. But a dried potato is what the mischievous kids get, while treats and other gifts are reserved for the good kids.

The Icelandic Christmas Foods

Laufabrauð

Laufabrauð, a layer of flat, circular-rectangular bread that is cooked in oil and then adorned, is one of the essential dishes in Iceland’s Christmas culinary heritage. The first Sunday in December is traditionally reserved for its preparation and storage in anticipation of Christmas Eve. A specialized knife known as a laufabrauðsjárn is used for the cutting process. Béchamel, potatoes, and smoked lamb are some possible accompaniments.

Laufabrauð has a long history, dating back to the 18th century, when it was a popular delicacy among the well-to-do.

In the 19th century, it became closely linked with Christmas. The once-exorbitant price of flour could explain its slender form.

Kæst Skata

As a long-standing custom, kæst skata, or fermented skate, is traditionally eaten on December 23, the night before Christmas Eve, on the feast day of St. Ðórlákur, bishop of Skálholt. A poll found that 100,000 Icelanders observed this tradition in 2013.