The National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) were both established in 1947 to serve as the primary intelligence agencies of the United States. Its responsibilities include overseas intelligence gathering, counter-espionage operations, and the study and development of new information-gathering techniques. While the CIA was either celebrated or criticized as a potent tool in the Cold War, its greatest failure occurred on September 11, 2001, when it failed to stop the attacks.

At the origin of the creation of the CIA: Pearl Harbor

Understanding the motivations for the CIA’s founding in 1947 requires looking back at the intelligence landscape at the time. Strangely, espionage did not have a positive reputation on either side of the Atlantic prior to World War II. Though he claimed to dislike espionage, Roosevelt relied heavily on intelligence from insiders, including a network of those closest to him.

While the Navy and the War Department’s intelligence agencies having their own webs of contacts in the region, the FBI managed to weave a few of its own. Nonetheless, the British, who were much more sophisticated in terms of intelligence collection, advised their American colleagues and helped them establish the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in 1942.

This organization was established to better use intelligence and make it more accessible. Even more so, given that the American armed forces had been caught off guard and unprepared for the devastating assault on Pearl Harbor that occurred on December 7, 1941, a few months before.

Donovan, widely regarded as the “founder of American intelligence,” was eventually given control of the OSS despite initial resistance from the Army. So was created the first civilian service, which not only enlisted the help of countless academics and the finest professionals to gather and analyze data, but also engaged in sabotage behind enemy lines and maintained communication with different resistance networks. The OSS was officially disbanded after World War II ended in 1945.

There was a multi-stage process involved in establishing the CIA. As the Cold War escalated and Truman sought to pursue his strategy of containment, it became clear that the United States needed a highly functioning intelligence agency.

However, Congress’ deliberations were heated as members worried about the rise of a centralized agency with too much authority. With the passage of the National Security Act in 1947, the Central Intelligence Agency was established after an earlier body charged with intelligence planning and organization was established in 1946 to work with the other American intelligence agencies. Its emblems are the Shield, representing the United States as a fortress, the Eagle, and the Star.

The “Ministry of the Cold War” and Secret Wars

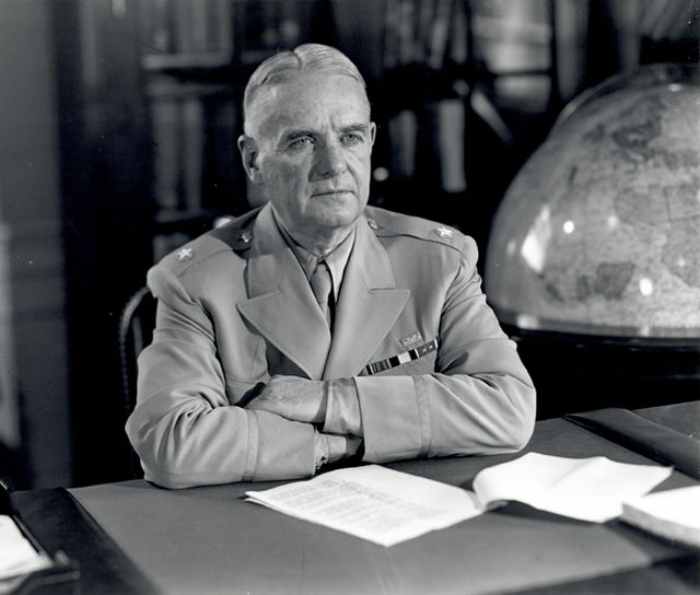

Initiated by the flamboyant Vandenberg and then taken over by the ex-military commander Hillenkoetter, the CIA’s original objective was to coordinate the efforts of the different intelligence agencies. The agency’s budget was gradually increased, allowing for new initiatives including espionage and covert acts, as well as the direct transmission of daily reports to the President.

The first major covert operation supported the Christian Democratic Party financially to stop the Communist Party of Italy from winning elections. It was planned for the CIA’s Office of Covert Operations (OPC) to fund numerous paramilitary organizations in the Soviet realm, namely in Ukraine, Poland, and Albania.

The first Soviet nuclear bomb detonated in 1949, which was a considerably more significant event given that the CIA predicted the USSR wouldn’t have nuclear weapons until 1953. The CIA blundered yet again when it failed to anticipate the outbreak of war in Korea. After a string of setbacks, Hillenkoetter resigned, and Walter Badel Smith, another military guy, took over.

The President relies on the CIA’s ability to predict and foresee the future. The agency’s funding was boosted, and it recruited and hired a large number of scientists, scholars, and historians to help it complete its objective. Accordingly, there is more emphasis on dissection. Furthermore, a research division was established to investigate the concept of mind control through tests conducted on either inmates or whores.

When Smith was in charge, the CIA became the only organization in the intelligence community allowed to engage in covert operations. As a result, the CIA established its credibility in the 1950s as a bona fide “Ministry of the Cold War.” It initiated close coordination with several foreign intelligence agencies, including those of Israel, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

With D. Eisenhower’s election as president, the United States entered a new era. Allen Dulles, one of the CIA’s most distinguished leaders, was chosen director of the agency by Eisenhower. Following in the footsteps of his predecessor, he was expected to increase the number of covert operations, the most noteworthy of which was the Guatemalan coup d’état of 1954.

Because of these achievements, the White House and even Congress began to back the Agency. At the same time, advances in technological intelligence led to many flights of the U2 spy aircraft over the USSR between 1956 and 1960, culminating in the plane’s crash on enemy territory and a resulting diplomatic crisis.

Damage done to the CIA’s reputation

Secret missions don’t always provide the desired results. As a result of the failure of the Bay of Pigs, an operation orchestrated by the CIA but with JFK’s full backing, Allen Dulles was ultimately sacrificed. Herein lied the tension between the White House and the CIA director: in the event of a failure, the latter was held accountable while absolving the President of any responsibility for the actions taken or the results achieved.

Director duties were given to Helms, a private citizen, after McCone’s death (he was vilified for his dissenting views on the Vietnam War). In the United States, the CIA spied on and even influenced the press and different groups during a period when pacifist movements were at their peak of intensity, acting outside of the law. Then, the CIA director, William Colby, leaked the affair to the public, along with the Watergate scandal, and it rocked the agency to its foundations.

The CIA’s reputation suffered and its use was called into question when it was viciously denounced by several public leaders in 1975, prompting the Representatives to consider instituting rigorous supervision of its actions.

The CIA’s “rebirth”

Langley, the CIA’s headquarters, was experiencing poor morale as a result of the agency’s current predicament. The situation was remedied by the appointment of George H. Bush as Director, since Bush was a politician and was therefore expected to withstand the mounting scrutiny from the press and the government. To meet the new demands of legality and legislative supervision, he restored a climate of trust inside the CIA and won widespread acclaim as a result.

Despite this, President Jimmy Carter in 1977, who placed little value on intelligence and appeared to dislike covert operations, did not rehire him. He then installed Turner, who was rapidly disliked by CIA employees because he focused on the Intelligence Community rather than the CIA itself. After the conclusion of his term, Carter relied on intelligence to accomplish his goals, whether it was improving relations between Egypt and Israel or coordinating covert operations in Afghanistan or Iran in the wake of the Islamic Revolution.

New momentum was provided by the election of Ronald Reagan, who, in Frank Daninos’s words, wanted to “untie the shackles of the CIA” to give himself all the tools he needed to beat the Soviet Union. Casey, the new director, increased the funding and the number of undercover agents. However, the Iran-contra controversy harmed the CIA’s reputation, since Reagan had considered allowing Iran to send weaponry to Lebanon via the CIA in exchange for the release of American embassy hostages.

Reagan is unscathed by this incident, and as usual, the buck stops with the CIA Director. Unfortunately, Casey passed away unexpectedly, and a strict FBI lawyer named William Webster took control. To legitimize his actions, he bolstered ties between the CIA and the FBI. In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, marking a triumph to which the CIA had undoubtedly helped but also reigniting the debate over the agency’s use at a time when the United States seemed to have no opponent.

Arguments that the CIA was useless in the first Gulf War and was clueless about modern terrorism threats reappeared. Thus, the new director, Robert Gates, attempted to reorganize the CIA so that it would be better able to deal with the shifting dynamics.

A difficult adaptation to new challenges

The CIA faced crisis after crisis during the 1990s. The CIA could no longer see clearly after the bombing of the World Trade Center’s basement in 1994 and the detonation of the first Indian nuclear weapon in 1998. Budget cuts and staff reductions have been made for a good cause.

On top of everything else, the FBI infiltrated the CIA to assume charge of anti-terrorism until the agency’s own employees pressured the head, Deutch, to step down. For over 50 years, the Pentagon deferred to the CIA as the premier intelligence agency. Taking advantage of this gap, the Pentagon steadily attempted to assume control of the CIA.

There was yet another change at the top, with Tenet becoming the sixth director in the last six years. This one received support from inside the CIA and aimed to elevate the Directorate of Operations. Plans to kill Bin Laden were thus developed, but never carried out due to the dangers involved. Bush hired him, and in August of 2001, he warned the president of the United States that an assault on American soil was possible in a report he submitted to the president.

The most well-known consequence was the 9/11 attacks. Despite several declassifications in response to a demand for openness, conspiracy theories emerged before the FBI’s and CIA’s many dysfunctions and poor coordination became public knowledge. There was a complete and utter failure in American intelligence, and the CIA would need to be revamped.

The CIA had to lead the charge in the fight against terrorism and the defense of the American empire, so George W. Bush visited Langley, doubled the agency’s budget, and restarted the hiring process. The CIA analysts needed to show that Hussein had WMD, which was the crux of the Iraqi problem. This incident started a fresh rift between Langley and the White House, which ultimately led to Tenet’s departure as director.

A bill reforming American intelligence was approved in December 2004, and the CIA stood to lose the most. The CIA director was no longer in charge of all American intelligence operations; that job now belonged to the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), who was formerly held by the head of the CIA. The CIA’s covert operations, however, were bolstered when they were brought under one umbrella at Langley. Once it happened, a new era for the CIA began.

The CIA’s origins may be seen as conflicted; it was established after the shock of a surprise assault, at a time when the United States was rising from isolationism.

There are ultimately multiple CIAs: the CIA of myths, created from the CIA’s involvement in coups d’état (Guatemala in 1954, Chile in 1973), which made the CIA a super-powerful agency with infinite tentacles; and a decried CIA, created from the scandalous experiments in which it was able to engage, which sparked numerous debates, including within the American political class.

Even if the CIA had a terrible time adapting to the post-Soviet era, it is clear that it is still a vital American intelligence entity that aids in the safety of American citizens and the defense of American interests abroad.