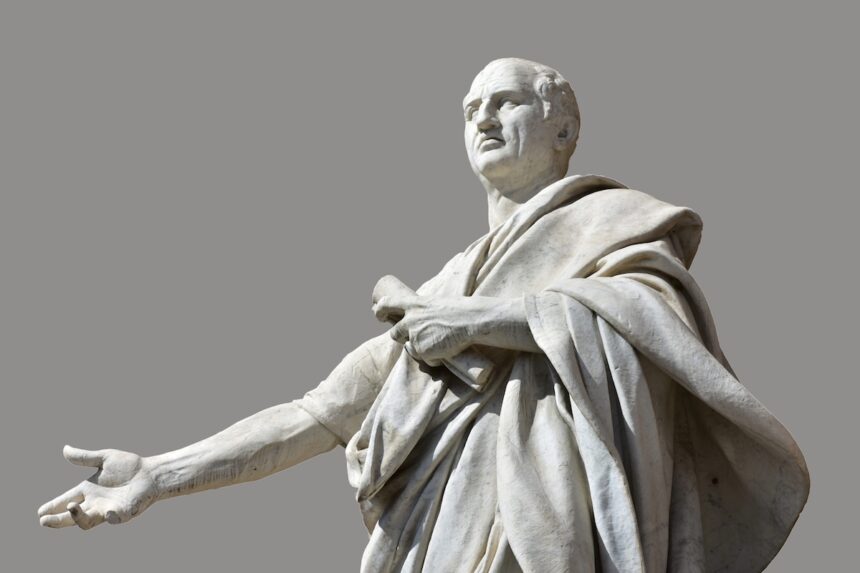

Marcus Tullius Cicero, known as Cicero (106-43 BCE), was a Roman writer, philosopher, lawyer, prodigious orator, and statesman, and one of the greatest figures in the history of ancient Rome. A fervent defender of the values of the Res publica, born four centuries before him, his life took place during the period of crises and civil wars that the Roman Republic was going through, which ended with his assassination. Cicero’s influence on Latin culture was considerable, affecting both the field of oratory, of which he was the first theorist, and political and moral philosophy.

Cicero’s Youth

Born into a plebeian family elevated to the equestrian rank, Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in 106 BCE in Arpinum, a small town located halfway between Rome and Naples. He was sent to Rome for his studies, where he was trained in Greek classics and introduced to public affairs. The Social War (90-88 BCE) erupted during his training, and he joined the army at the age of seventeen. He was placed under the command of Sulla and met Pompey, with whom he would remain closely connected. Military service was essential for a political career in Rome, but Cicero was not particularly drawn to military life. He left the army at the end of the conflict in 88 BCE to return to his studies, while Marius and Sulla fought for power, plunging the Republic into its first civil war.

Cicero completed his education by studying law, history, philosophy, dialectic, and rhetoric. He followed the teachings of Epicureans, Stoics, and Platonists and spent a few years in Athens to perfect his education. He became a master of oratory, both in his diction and the quality of his arguments. Cicero was a Homo novus, a citizen whose ancestors had never held public office, but his marriage to Terentia, a woman from the wealthy and influential Roman family, the Terentii, opened doors to the high aristocracy. This network of alliances was essential for rising through the Cursus honorum, the Roman path to public offices.

An Engaged Roman Citizen

Cicero won his first trial in 81 BCE in a succession case involving parricide. When he was old enough to apply for public offices, he began his ascent through the Cursus honorum. In 75 BCE, he was elected quaestor in Sicily. In 70 BCE, he gained popularity by defending the Sicilians and winning his case against the Roman statesman Gaius Licinius Verres, who was involved in numerous thefts and corruption scandals.

This case truly marked his entry into judicial and political life. Cicero presented himself as a lawyer committed to fighting corruption and published the Verrines, a collection of speeches against Verres.

In 66 BCE, he became praetor, one of the highest Roman magistrates, representing the centrist path of the Viri boni (“men of good”) between the optimates, who were conservative and aligned with the aristocracy, and the populares, who were reformers sensitive to popular and social demands. The first defended class interests, while the latter often succumbed to populism. Today, this could be simplified as a division between the right and the left.

The Conspiracy of Catiline

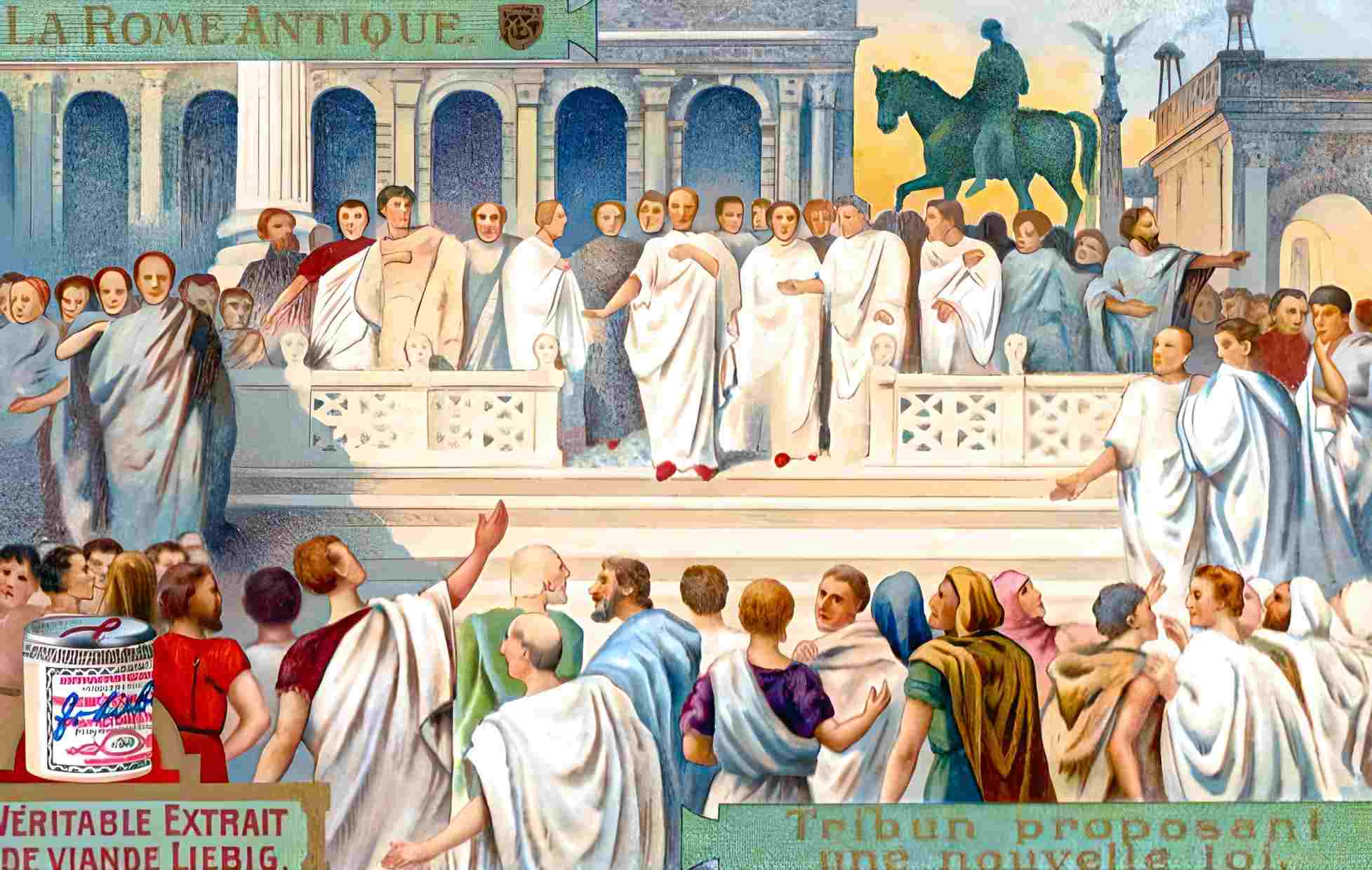

In 63 BCE, Cicero was elected consul, defeating Senator Lucius Sergius Catilina. Catiline already had a dubious past. In 66 BCE, he had conspired to give the dictatorship to Marcus Licinius Crassus, the general who defeated Spartacus and the wealthiest man in Rome. Furious at his failure to win the consulship, this time Catiline wanted to seize power personally. Presenting himself as a defender of the oppressed, he took advantage of Pompey’s absence, who was campaigning in Asia, and relied on the frustrations of a portion of the Roman nobilitas and provincial notables to organize a coup.

Cicero was informed of this plot and, on November 8, 63 BCE, he addressed the Senate, harshly confronting Catiline: “How long, Catiline, will you abuse our patience?” In this speech, in which he exposed the details of the conspiracy and the threat it posed to the security of the state, he uttered the famous proverbial phrase O tempora! O mores! (“Oh what times, what customs“).

Exposed, Catiline defended himself clumsily and was forced to leave the assembly amid jeers from the senators. That evening, he fled Rome to join a camp in Etruria, where he had begun assembling troops. In the following weeks, the names and plans of the conspirators were quickly revealed through investigations, and they were all arrested, except for Catiline, who organized an uprising in Etruria. Senate sessions followed to decide their fate, and on December 5, after a final debate, they were sentenced to death without trial.

The execution took place immediately after the session, and Cicero sent the army to crush Catiline’s uprising. Unable to gather enough troops, Catiline fled towards Transalpine Gaul. He died on January 5, 62 BCE, during a violent battle in which all the conspirators were killed on the battlefield. Presenting himself as the savior of the homeland, Cicero announced to the people that, thanks to him, the conspiracy had been defeated.

Cicero on the Path to Exile

Hailed as Pater patriae (“Father of the Fatherland”), Cicero gained great popularity from these events, and the publication of the Catilinarians, the speeches he delivered in the Senate during this episode, further enhanced his prestige. Now a member of the Roman Senate, Cicero was also a wealthy man, owning a sumptuous domus (palace) on the Palatine Hill, several villae rusticae (agricultural estates) in the countryside, and comfortable villae urbanae (country residences) in the provinces.

However, his fortune, primarily based on land assets estimated at 13 million sesterces, was far from matching that of Rome’s wealthiest citizens, like Crassus, whose wealth sometimes exceeded 100 million sesterces. Moreover, his senatorial status prevented him from engaging in commercial or financial activities.

Though he had stepped back from political life, Cicero faced increasing criticism. His excessive vanity and self-praise irritated the Romans. When the First Triumvirate was formed—a secret political alliance between Pompey, Caesar, and Crassus—he refused to join. He also had political enemies, particularly the tribune of the plebs Publius Clodius Pulcher, who harbored a deep hatred for him. In 58 BCE, his enemies proposed a law condemning any magistrate who had executed a citizen without a proper trial, explicitly targeting Cicero for the execution of Catiline’s supporters.

Deprived of support, Cicero hastily left Rome the day before the vote on this law and took refuge in Dyrrachium (modern-day Albania). His domus was destroyed, and bloody clashes ensued between his supporters and opponents. Eventually, Pompey secured the passing of a law nullifying Cicero’s exile and restoring his property. After sixteen months of exile, on September 5, 56 BCE, he returned to Rome, where he received a triumphant welcome.

Return to Politics

Cicero attempts to return to politics, and without attacking the triumvirs directly, he targets their protégés. He calls for a Republic united by all the “good citizens,” where they would not necessarily have the leading role. In De Oratore, he emphasizes that a great orator must hold a prominent place in the city, and in De Re Publica, he hints that he sees himself as one of the guardians, if not the guardian, of the Republic. This doesn’t sit well with the triumvirs, who rein him in. Pompey reminds him of the protection he owes him, and Cicero is obliged to support, before the Senate, the extension of Julius Caesar’s proconsular authority over Gaul.

In 51 BC, Cicero is granted a proconsular mandate in Cilicia, a small Roman province in Asia Minor, which he governs, according to Plutarch, with a sense of integrity and justice, even though he takes on this role without much enthusiasm. He applies his philosophy of provincial governance, focused on peace and justice, particularly fiscal justice, eliminating unjust charges. However, he is forced to quell a revolt and raises troops. After two months of siege, the insurgents capitulate, and for this relatively modest achievement, Cicero is proclaimed imperator by his soldiers.

This title, given during the Roman Republic to victorious generals upon their return from military campaigns, inspires Cicero to seek a triumph when he returns to Rome, but that will not happen. He returns to Rome a year later, just as the civil war between Caesar and Pompey is about to break out. Crassus had died fighting the Parthians in 53 BC, and Pompey had taken advantage of Julius Caesar’s absence, who was occupied with his conquest of Gaul, to be named sole consul by the Senate.

Cicero was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, particularly Stoicism, Platonism, and Epicureanism. He sought to adapt these schools of thought to Roman culture and politics. His philosophical works, such as “De Officiis” (On Duties), “De Re Publica” (On the Republic), and “De Legibus” (On the Laws), explored topics like morality, justice, and the ideal government, emphasizing the importance of virtue and the rule of law.

Civil War

In January 49 BC, declared an outlaw by the Senate, Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon at the head of his legions and marches on Rome, while Pompey and his supporters flee. Caesar installs a Senate loyal to him, through which he obtains the consulship and then the dictatorship. He offers Cicero, who, like most senators, had fled Rome and taken refuge in one of his country houses, the role of mediator. Distressed by the civil war, which he views as a calamity, Cicero declines but sides with Pompey, whom he joins in Greece without participating in military operations.

After Caesar’s decisive victory over Pompey at Pharsalus in 48 BC, Cicero abandons the Pompeian camp and returns to Rome. Caesar shows kindness toward him, and Cicero praises his clemency. Their relationship remains cordial, but seeing the reality of Caesar’s absolute power and the end of the Republic, Cicero prefers to withdraw from politics.

Nevertheless, he writes the Eulogy of Cato, whom he calls the “last Republican,” to which Caesar responds with his Anti-Cato. Cicero’s personal life is also troubled. In 46 BC, he divorces his wife Terentia and soon after marries Publilia, a very wealthy young woman, whom he also divorces after the death of his daughter Tullia, which causes him profound grief.

Death of Cicero

Cicero then spends most of his time at his villa in Tusculum, dedicating himself to literature, philosophy, and even poetry. The assassination of Caesar on March 15, 44 BC, puts an end to this peaceful retreat. Hating Mark Antony, who positions himself as Caesar’s executor and takes power, Cicero defends the Republican cause and attacks Antony in a series of increasingly violent speeches, the Philippics. He tries to have Antony declared a public enemy by the Senate.

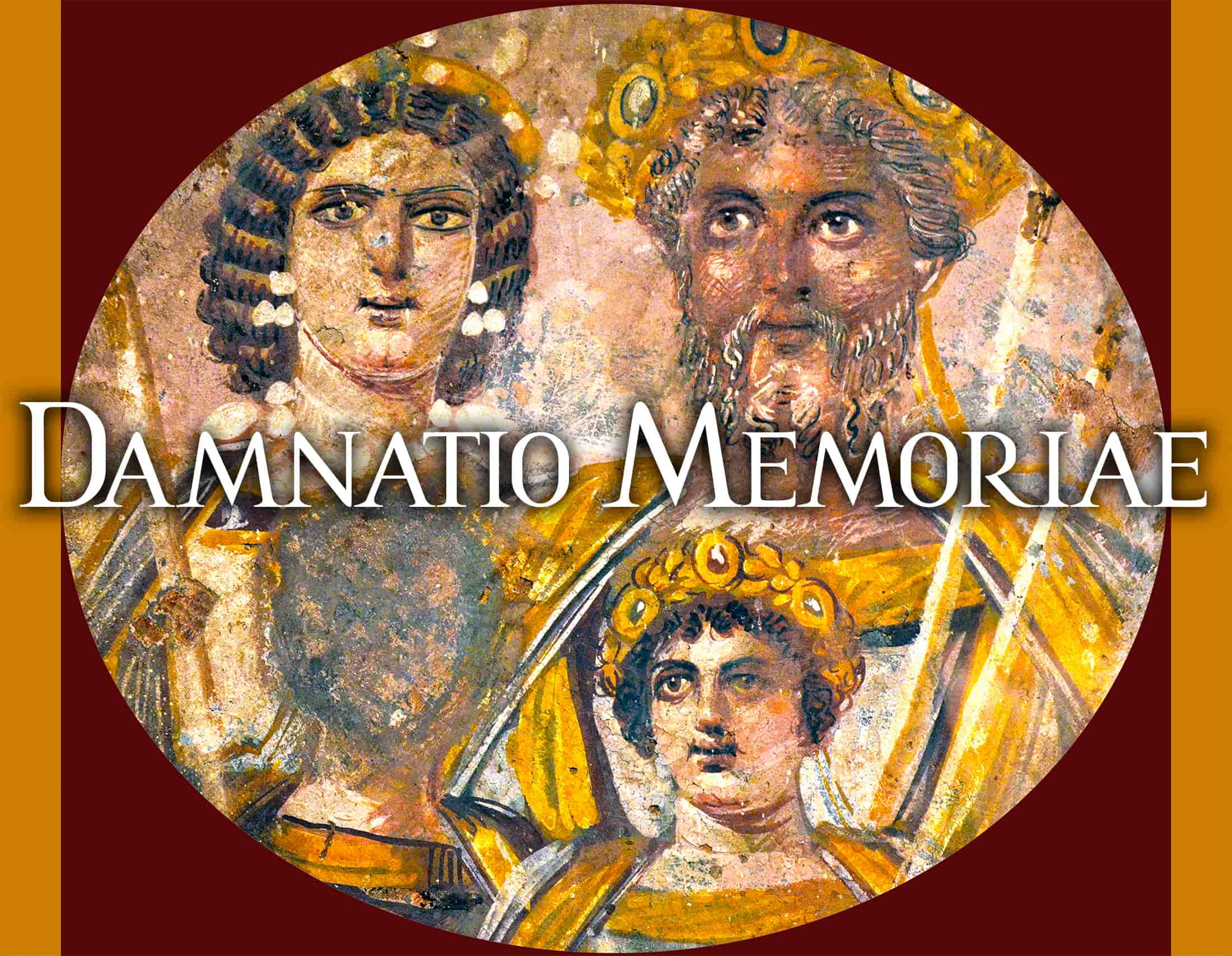

Cicero attempts to influence the young Octavian, but Octavian allies with Mark Antony and Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate. The three men agree to avenge Caesar’s murderers, but also to eliminate their personal enemies. Mark Antony demands Cicero’s head, and Octavian allows it.

On December 7, 43 BC, Cicero is assassinated in his villa at Formia. His head and hands are cut off and displayed in the Forum in Rome by order of Mark Antony. His brother and nephew are executed shortly afterward, and only his son, who was in Macedonia at the time, escapes Mark Antony’s fury.

Works of Cicero

Due to the breadth, variety, and quality of his literary output, Cicero is considered the greatest classical Latin author. He left us a significant body of work, consisting of his legal pleadings and speeches, treatises on rhetoric, philosophical works, extensive private correspondence, and even poetic compositions. An exceptional orator, his rhetorical art had a significant influence on Western culture from Antiquity through the modern era.

Often considered merely a compiler of Greek philosophers, Cicero had made it his mission to popularize Greek philosophy in Latin for a Roman audience. In the political realm, judgments are more severe, and some historians have seen him as an intellectual lost amidst a den of political intrigue.

A staunch opponent of corrupt politicians and enemies of the state, such as Catiline, Cicero believed in the values of the Roman Republic and sought to preserve it from ambitious individuals and totalitarian tendencies. However, he could only watch helplessly as Pompey and Caesar rose to power.

Cicero: Key Dates

January 3, 106 BC: Birth of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero, known as Cicero, was born on January 3, 106 BC, in Arpinum, Italy. He came from a wealthy and respected family due to their equestrian status. As a child, he studied Greek philosophy and later became a lawyer.

75 BC: Start of his political career

He began his political career by becoming quaestor in 75 BC, gradually climbing the ranks. In 69 BC, he became aedile, in 66 BC praetor, and in 63 BC he was elected consul. His political career was marked by his oratory skills, which earned him his reputation.

63 BC: The Catiline Conspiracy

Cicero had just been elected consul when his opponent, Catiline, decided to seek revenge by attempting to overthrow the government. Cicero managed to thwart his rival’s plans. His writings, the Catilinarians, bear witness to these events. He then had the conspirators executed without a public trial.

August 9, 48 BC: Pompey defeated by Caesar

Julius Caesar pursued and crushed the forces of his rival, Pompey, at Pharsalus in Thessaly. A year earlier, after Caesar had crossed the Rubicon (a river separating Gaul from Italy), Pompey and the senators had abandoned Rome and sailed for Greece. Defeated by Caesar, Pompey sought refuge in Egypt with Ptolemy XIII, but fearing Caesar’s retaliation, Ptolemy had him assassinated.

December 7, 43 BC: Assassination of Cicero

The Roman senator Marcus Tullius Cicero, known as Cicero, was killed near his villa in Formia by men loyal to Marc Antony, the new strongman of the Roman Empire. His head and hands were displayed on the rostrum. Since coming to power with Octavian and Lepidus (the triumvirate of November 11), Marc Antony had been determined to punish those who conspired against Caesar. Around a hundred orators were assassinated, just like Cicero.