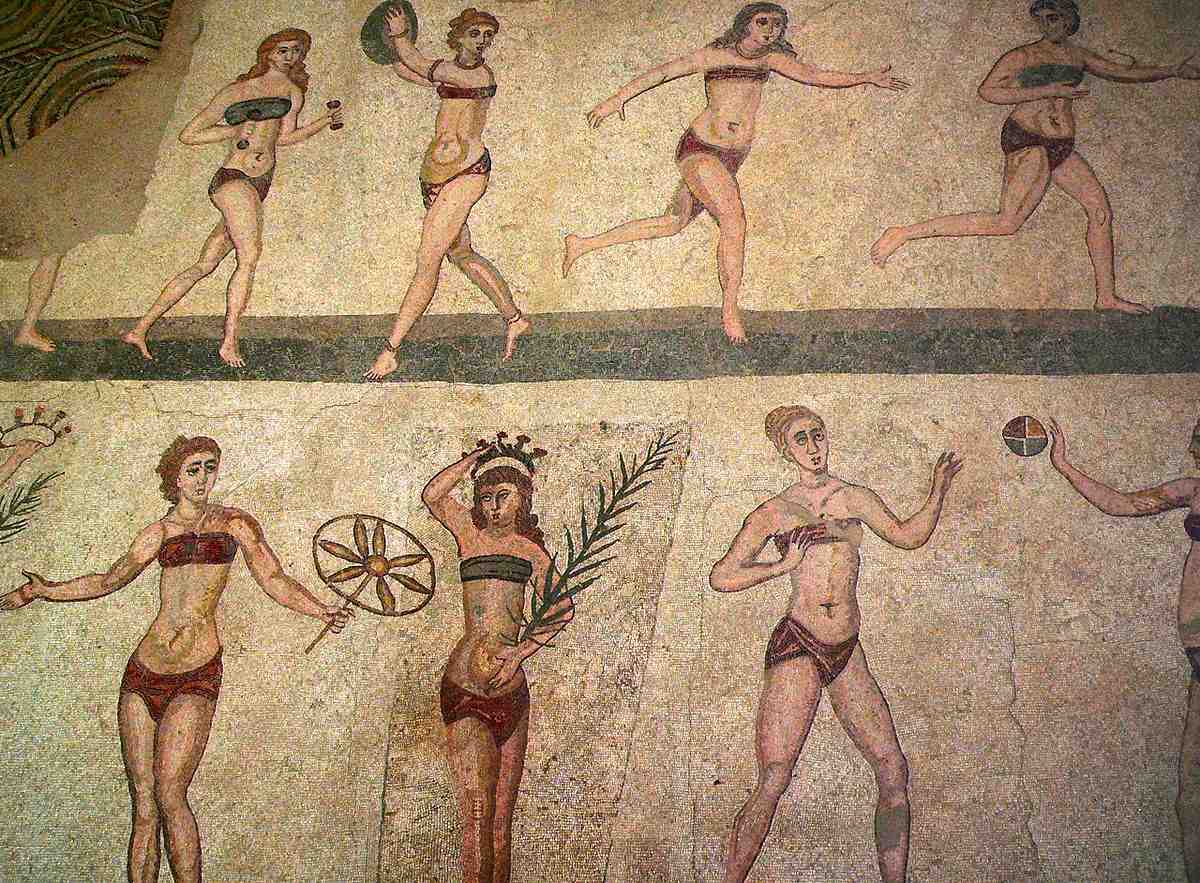

One half of ancient Rome’s population was made up of women; however, our understanding of their lives was limited. While we can learn a lot about ancient societies through statues and wall paintings, we have to rely on writings by men to learn about the practices of personal cleanliness and cosmetics of ancient women. In this article, we’ll explore the experiences of Roman women at the outset of the Roman Empire, when they were beginning to be recognized as individuals apart from their husbands.

The bathing and showering in Ancient Roman women

How near I was to warning you, no rankness of the wild goat under your armpits, no legs bristling with harsh hair!

According to the poetry of Ovid.

At the close of the Roman Republic, Roman males and females began placing a premium on physical beauty. The Romans thought that the body was flawed and incomplete by nature, so it had to be taught and trained to move away from its animal roots.

According to Seneca, the standard practice in the countryside was to shower daily, but only after getting dirty at labor (arms and legs), and to wait a week or nine days before showering again (market days). In the past, home hygiene only concerned the personal care of females and the youngest members of the household.

Only the wealthy residents of the city could afford private baths; everyone else had to rely on the public baths. Since Hadrian’s reign, and in response to a scandal, an imperial edict has mandated separate hours (morning for women, afternoon for men), with the exception of specific businesses (Pompeii) that were open at both times. On the other hand, a lady who was worried about what other people would say decided to stay away from the pool because of the presence of men and women. The wealthiest ladies indulged in milk baths (of sweet almond for Cleopatra, of ass for Poppea). Wrinkles might be reduced by using a variety of remedies, including donkey’s milk, crushed white vine, diluted pigeon droppings in vinegar, or oily fluid extracted from sheep’s wool.

The Romans did not have soap, so they washed with a sponge and degreasing ingredients and then used a strigil to remove dirt.

- Saltpetre foam

- Sapo: Foaming paste made of goat fat and beech ash (invented by the Gauls)

- Lomentum: Made from bean flour and plucked snail shells

- Pumex: Pumice stone

Due to the abrasive nature of these cleansers, it was necessary to apply ointments or moisturizing lotions containing scented oils all over the body after each washing to restore the skin’s softness and suppleness.

These lotions were made by combining cereal drink froth with lanolin taken from sheep’s wool and then scenting them to cover up the noxious odor. Some common ingredients in homemade beauty masks were wheat flour, donkey milk, boiled sturgeon glue, sulfur, orcanet, silver foam, water, and eggs. To avoid irritation and redness, these plasters could not be left on for more than a few hours. An anti-inflammatory remedy that included frankincense gum, myrrh, and nitre, diluted in honey and seasoned with fennel and dried roses, was effective in most situations. Cucumber juice, calf dung mixed with gum, and oil could all help diminish freckles.

Pliny the Elder’s book Natural History (Naturalis historia) contained a plethora of recipes. While many of these items were claimed to be moisturizers, they actually produced lesions ranging from mild to severe and always required more maintenance or concealer. Ointments made with oil were the safest option. Alum stone was also used by the Romans as a deodorant.

Dentifricum (Dentifrice) was a powder made from soda (also known as “nitrum” or “saltpeter”) that was used for oral hygiene. Some people even tried using horse ashes, pumice powder, or urine. For a minty-fresh mouth, one could chew on a lozenge made from myrtle or mastic that had been soaked in a mixture of old wine, ivy berries, cassia, and myrrh. Pliny the Elder advised using stag horn ash as a friction or mouthwash to relieve tooth pain. Many had said that stag horn powder that had not been burned was more potent.

The Greeks employed a feather (Martial) or a “dentiscalpium,” which could be fashioned of metal, bone, or wood and resembled a toothpick but was completed with a hook. Some were designed to be used as toothpicks or earpicks.

Rings, toothpicks, tweezers, a tiny nail-pick knife, a lice scraper, and a variety of makeup spatulas were all examples of items that could be found in a toiletry kit.

Hair removal in Ancient Roman women

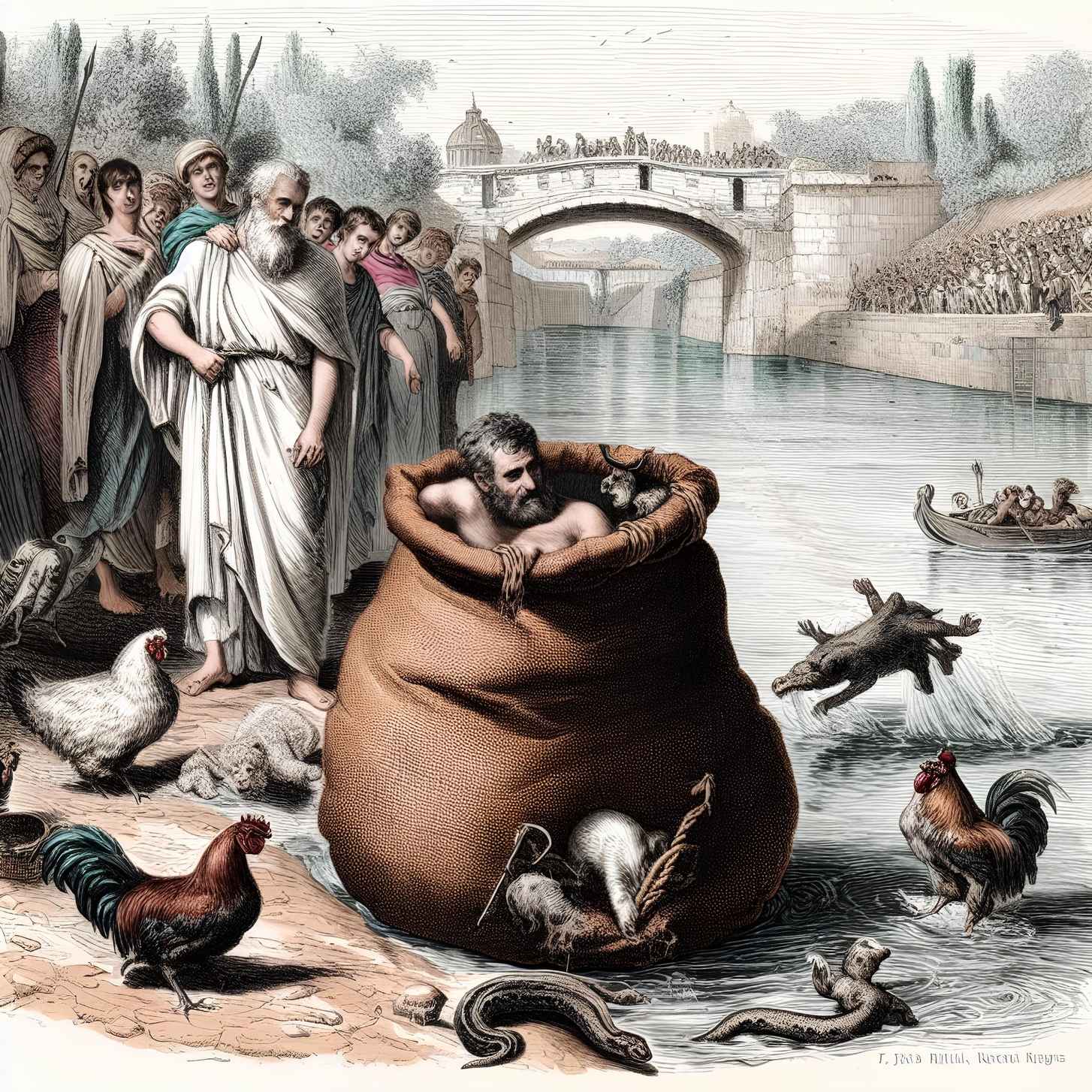

Women used a depilatory cream made of rosin (pitch) dissolved in oil, which was occasionally combined with resin, wax, and a caustic ingredient to remove hair from their underarms and legs. Some women used a mixture of equal weights of black elderberry seed from Armenia and silver lye as an alternative. Others favored a wax made from pine resin. Bronze tweezers, ranging in size from 5 to 11 cm and resembling our own in design, provided a simpler alternative for ladies. Augustus, who would burn his legs with walnut shells heated to white to make his hair come back softer, was just one example of a man who waxed both his body and face.

Makeup was only an option for Roman women after they had spent hours perfecting their appearance. But a woman should never show a man, especially her partner, how she cleans herself.

The makeup of Ancient Roman women

When applying cosmetics, a Roman woman would use a highly polished bronze or precious metal mirror, which was occasionally silvered for a more accurate reflection. Roman women, to the chagrin of men like Seneca, resembled prostitutes (or lupa) due to their excessive use of cosmetics. Makeup was often applied after skin care routines had been completed. They used vivid, clashing hues.

A flawless complexion was all the rage. A woman’s worth was diminished if her face was excessively red, as this indicated that she was very active. On the other hand, paleness was a sign of female emotional distress and had to be avoided at all costs. White ceruse (lead carbonate) was used as a foundation, and it was sometimes combined with honey or another fatty ingredient to create a “youthful whiteness.” (Ceruse came from Rhodes and was very toxic; it had been banned in France since 1915). Saltpeter foam, Selina earth (yellow ochre), wine lees, or fucus were used to add color to the white (red algae).

To further emphasize the narrowness of the forehead, the eyebrows were drawn up and made longer (another beauty criterion). Using a brush, antimony, often known as “smoke black,” was placed on the outer corner of the eye to accentuate the lash line. Then, either green (from malachite), blue (from azurite, copper carbonate), or red (from hematite) was applied to the upper eyelid (dye made from Cydnus saffron). A dab of crimson blush was applied with a brush, and a beauty spot was placed on each cheek to finish off the makeup.

Crushed hematite (iron oxide) crystals were used to add a touch of sparkle to the face for special events. Small, cylindrical bone pyxes or glass bottles housed the powders and creams, and a spatula or spoon made of bone, metal, or glass was used to remove the contents. To prepare the concoctions, they utilized little glass bowls.

All of this attention to the body was done according to the family’s resources, but even the most humble people would take care of themselves and apply makeup, using various materials (such as poppy flowers instead of saffron for the red) to appear beautiful under a lovely sky. Many of these items caused skin problems and may have even caused malignancies.”

Bibliography:

- Beryl Rawson, “The Roman Family,” in The Family in Ancient Rome: New Perspectives (Cornell University Press, 1986), p. 18.

- Catherine Salles, La Vie des Romains au temps des Césars, éd. Larousse, coll. L’Histoire au quotidien, 2004

- Kelly Olson, “The Appearance of the Young Roman Girl,” in Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture (University of Toronto Press, 2008), p. 143.

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History.

- Janine Assa, The Great Roman Ladies, New York, 1960