Commodus was a Roman emperor (180-192), the son of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. His reign was characterized by violence and debauchery. In Roman historiography, the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, to which Commodus belonged, is considered the zenith of the Roman Empire.

The emperors of this period, including Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, and Lucius Verus, are generally portrayed, with a few exceptions, as competent rulers. Marcus Aurelius, who concludes this list (his co-emperor Verus having died in 169), symbolizes the concept of a moderate emperor. However, his succession gave rise to a complex series of events in which the gladiator emperor was not the sole architect.

—>Commodus’ reign is often seen as a turning point in Roman history, symbolizing the decline of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty and the onset of the Crisis of the Third Century. His rule is considered a contributing factor to the challenges faced by the Roman Empire in the subsequent years.

Commodus: A Birth in Purple

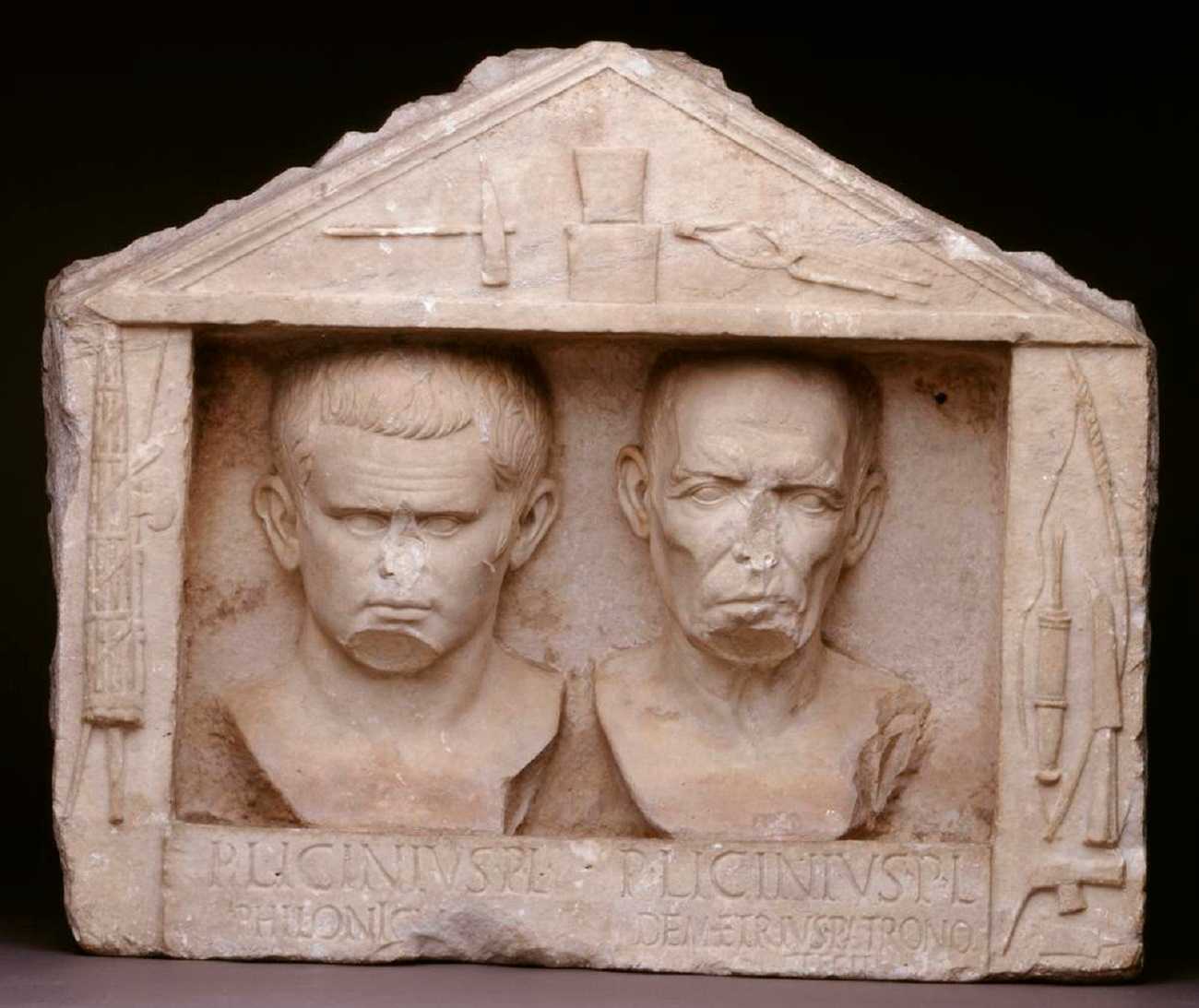

Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus was born on August 31, 161, just as his father, Marcus Aurelius, ascended to the throne of the Empire with Lucius Verus. He received an excellent education quickly, with many tutors among the most renowned of the time undertaking the education of the young prince. We can easily observe that the emperor was undoubtedly preparing his son to succeed him, although this was not the norm in imperial succession.

Indeed, at that time, the Nerva-Antonine dynasty was purely artificial in our contemporary view, with emperors rarely having family ties. The prevailing practice was the adoption of the one the emperor deemed most worthy to succeed him, as Nerva did with Trajan. The hereditary succession between Marcus Aurelius and Commodus appears to be unique to that era.

The Romans had experienced numerous incidents with emperors inheriting power from their fathers, such as Domitian. Herodian, highly nostalgic for the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher emperor par excellence, full of temperance and virtue, the symbol of a good emperor, describes the reservations the ailing emperor may have had about handing over the Empire to his son.

He speaks of concerns about the young age of the prince and the risk posed by the loss of a father, the pater familias, whose authority had greatly weakened since the early days of the Republic but remained crucial for the Romans. The young man found guidance from his father to become a moderate man: “He is barely entering adolescence, and in this stormy sea of life, he needs wise pilots to guide his inexperience and prevent him from straying from the right path to break against the reefs of vice” (Herodian I, 4). He also mentions the risk of barbarians, already very dangerous during his reign, who could take advantage of the new emperor’s inexperience to attack.

However, as Marcus Aurelius lay dying, he gathered his close associates, high dignitaries of the Empire, and his son. He urged them to take the greatest care of their son’s education and replace him in his role as a father. Under no circumstances did the emperor wish to entrust the Empire to another, as was customary.

Designated, Commodus thus began his reign with the legitimacy of heredity and education suited to his task, well explained in his words: “Today fate calls me to succeed him on the throne, not like those princes, my predecessors, who, strangers to power, reached it proud of their fortune. Alone, I was born; I was raised for you near the throne; my cradle was not that of an obscure child; at the moment of leaving my mother’s womb, the imperial purple embraced me, and the sun saw me both a man and a monarch” (Herodian I, 5). Hence, we clearly see that the prince’s assumption of power is by no means an impulsive act but a deliberate intent of Marcus Aurelius.

Early Reign of Commodus

Shortly after death, Commodus was introduced to the soldiers, as was customary, with the power of imperium originally designating the authority to command, especially over the soldiers. On this occasion, Commodus, in his discourse, informs us that Marcus Aurelius exposed him to the troops and confronted him with military matters, as that is where the emperor should be during times of war.

Subsequently, the new prince received counsel from his father’s advisors until characters, described as vile flatterers by Herodian, began to corrupt the prince by introducing him to various delights and pleasures. On this matter, one can question the orientation of these men, primarily in relation to the ideological stance of the majority of the Roman nobility then in power.

Indeed, Marcus Aurelius and many writers of the time were staunch Stoics, individuals who made their existence a pursuit of virtue through the mastery of the body and emotions while rejecting pleasures. This philosophy directly influenced Christian morality. Other past monarchs of the dynasty, as well as many others, also had a certain sympathy for this philosophical orientation. However, the pursuit of pleasure was an opposing view found in Epicureanism. Therefore, one can undoubtedly question the choices of the young prince and his friends and thus the hatred that his choices will provoke.

Commodus even questioned his father’s associates with these words: “When will you cease, they said, O our august master, to drink icy water, drawn with effort from the bosom of the earth? Others will peacefully enjoy these lukewarm springs, these cool streams, these zephyrs, and this sky that only Italy possesses.” But this was hardly in line with the political realities of the moment; Marcus Aurelius had indeed died on the Danubian borders, leaving his son to finish the war. However, Commodus wished to return to Rome, which he did, delegating the defense of the borders to his generals.

Influence of Perennius and the Attempt on His Life

Upon arriving in the city of Rome, the crowd pressed in to meet him and paid him a vibrant homage. The senators welcomed him, and he visited the temples before finally retiring to his palace. His reign followed the precepts of his father, heeding the advice of high-ranking individuals. However, Herodian speaks of a man, Perennius, whose military talents led Commodus to appoint him as the commander of the Praetorian Guard. According to the author, Perennius made slanderous accusations against the former advisors of Marcus Aurelius. Yet it was his sister, Lucilla, formerly married to Lucius Verus, who, along with her then-husband Pompianus, first conspired against Commodus.

The hired assassin, Quintianus, rushed at Emperor Commodus with a dagger in hand outside the amphitheater, proclaiming, this is what the Senate sends you! (Herodian, I, 8). Arrested by the guards and killed on the spot, the man had, according to Herodian, initiated a change in Commodus’s attitude, especially towards the Senate. Perennius then seized the opportunity to eliminate his rivals, up to Lucilla, and thus exert his influence on the prince. However, soon his influence crumbled; indeed, his son, commanding troops in Illyria, had coins struck in his image, displaying a certain imperial pretension. Commodus had both of them eliminated. From then on, he chose two individuals to command the Praetorian Guard.

Troubles Sown by Maternus

Maternus, initially designated as a soldier, embarks on increasingly large-scale brigandage operations in both Gaul and Spain. Commodus reprimands his generals for these actions and gives them instructions to put down the uprising. Meanwhile, Maternus, having crossed into Italy, harbors imperial ambitions. In the capital, an event could play in his favor:

Every year, on a set day at the beginning of spring, the Romans celebrate a festival in honor of the mother of the gods [Cybele]. All the valuable trappings of each deity, the imperial treasures, and marvelous objects of all kinds, both natural and man-made, are carried in procession before this goddess. Free license for every kind of revelry is granted, and each man assumes the disguise of his choice. No office is so important or so sacrosanct that permission is refused anyone to put on its distinctive uniform and join in the revelry, concealing his true identity; consequently, it is not easy to distinguish the true from the false.

Source: Herodian, I, 10.

He aimed to conceal himself and his accomplices in the crowd and assassinate the emperor. He was betrayed by his men, who, according to Herodian, could not endure obeying him, considering him nothing more than a brigand like themselves.

Tormented Roman Emperor and Cleander

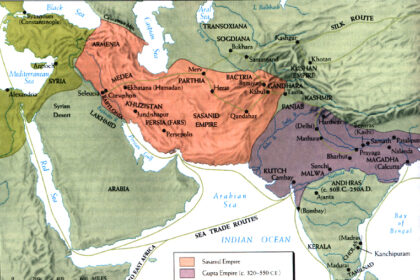

In any case, the foiled assassination increasingly diverted Commodus from the conduct of state affairs. He rarely stayed in Rome from then on. Moreover, a resurgence of the plague, a generic term used by ancient authors to refer to contagious diseases—in this case, a resurgence of the disease brought from Persia by the soldiers of Lucius Verus—struck again in the Empire. On the advice of his physicians, Commodus went to Laurentum, a place known for its salubrity.

At the same time, Cleander, a freedman of the emperor—that is, a former slave who owed his freedom to his former master—had become very close to Commodus and provided close services to the prince. Herodian recounts that he wanted to gain the favor of all to enjoy more power and fame. It seems that this was the reason that led him to buy large quantities of wheat, later distribute it, and present himself as a savior.

This practice is not unfamiliar to antiquity; in Athens, the wheat merchants, bringing it from the Black Sea, used to wait for famine to declare in the city to unload and thus raise prices. Cleander’s intentions, regardless of his ultimate goal, caused hunger in Rome.

The people then went to the imperial residence to demand explanations from the emperor, who was unaware of the situation. The freedman then ordered the cavalry guard to charge the crowd, massacring some of the assembled people.

The disorder led to a general stampede that resulted in the deaths of many more people. Herodian is indignant at such behavior, expressing what a disgrace it was to shed the blood of Roman citizens. The skirmish continued in Rome itself, where the crowd, from the roofs to the streets, made the soldiers pay for the deaths of their own. Given the magnitude of the event, the author is undoubtedly exaggerating. Finally informed by another of his sisters, Fadilla, Commodus summoned Cleander and immediately had his head cut off and carried to the scene of the tumult to put an end to the clashes.

Gladiator Emperor

Commodus entered Rome, despite his fears, and eased tensions. Herodian then extensively elaborates on the vices of the prince, aligning precisely with everything virtuous men despised. He emphasizes the emperor’s behavior, engaging in chariot races, participating in venationes—the hunting of wild animals—and even stepping into the arena as a gladiator.

It is essential to note that, during this period, young individuals of noble lineage developed a taste for risk, the picturesque, and the wild aspects of life, indulging in various “exploits,” including gladiatorial combat. Commodus is not a departure from this somewhat rebellious trend.

—>While Commodus is one of the most well-known emperors to engage in gladiatorial combat, he was not the only one. Some earlier emperors, like Nero, had also participated in such events, but Commodus is particularly infamous for his enthusiasm for the arena.

Prodigies and Divination

Wonders would have then occurred in great numbers in Rome, notably a fire. For the Romans, the interpretation of natural or non-natural events falls within the sacred domain. Haruspices can decipher these signs and determine whether they are positive or negative. In the mind of Herodian, when he composed his work, this element served to explain the future decline of Commodus as a divine will, conveyed to humans through these signs.

It was at this moment that the most megalomaniacal excesses of the emperor took on a particularly exuberant turn; he would have then proclaimed himself the son of Jupiter, calling himself Hercules and donning a lion’s skin, as observed in a bust that has reached us.

In any case, one thing is interesting here: Herodian strongly criticizes him, stating that he wore at the same time a tunic embroidered with gold and wealth. This is indeed an element that Roman traditions categorically rejected, as the emperor was not a king but a magistrate, the first among citizens.

However, by the end of the third century, Emperor Diocletian instituted the oriental ceremonial, with the attire of the prince becoming very rich, adorned with embroidery, gold, and precious stones, as well as the diadem, which was foreign to the early centuries of the Empire.

The future development of the reality of imperial dignity changes how Commodus behaved in a way that fits with how imperial power is becoming more open about its real power and pulling away from its republican roots.

Last Excesses

Indulging ever more openly in his passion for arena combat, Commodus eventually, as per Herodian, wearied the people who had previously admired him. His strong inclination for games led him to desire to appear fully armed in the arena during the Saturnalia festival, a true affront to imperial dignity for the Romans.

His close associates attempted to dissuade him from this course of action. Enraged, one evening he allegedly recorded a list of the names of senators and high-ranking officials he wished to see perish to ensure his tranquility. Marcia, his favored concubine, who had also tried to reason with him, found her name on the ominous list. However, a child attached to the prince entered his chamber and, in a playful manner, took possession of the tablets. Upon encountering Marcia, she recognized Commodus’s handwriting and discovered the emperor’s intent.

Herodian then provides what the concubine is said to have uttered, concluding with: “But a man always immersed in intoxication will not triumph over a sober woman” (Herodian, I, 17). This formulation is intriguing; the author distinctly contrasts sobriety, a fundamental virtue of a Stoic, with Commodus’s behavior, more aligned with an Epicurean approach.

Commodus’s Fall

Faced with this discovery, Marcia alerted the senators and informed them of the emperor’s intentions. They thus agreed to poison him. The concubine then presented him, after his daily exercises, with a cup of wine, as usual, but laden with poison. Commodus, dizzy, went to rest. Overcome by nausea, he began to vomit, to the point that the conspirators feared he might manage to expel the toxic substance he had ingested. They bribed a certain Narcissus, who then strangled him.

This is how Commodus died on December 31, 192, after thirteen years of rule. Despite his detachment from state affairs, the conduct of his power reveals the profound reality of the imperial regime—the enormity of its power and the paradoxical weakness of those who held this office.

Perhaps less ignoble than often portrayed, Commodus appears as an emperor more concerned with his pleasures than with the conduct of affairs. This contrasted sharply with the reign of Marcus Aurelius, who assumed his duties with impressive selflessness. With him, the Nerva-Antonine dynasty perished, marking the onset of a troubled era.

Commodus’ Reputation Over the Centuries

Commodus is one of those emperors whose name continues to evoke passion to this day and is often portrayed in cinema. The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) and more recently the film Gladiator (Ridley Scott, 2000) invite us to confront this emperor once again, who is, to say the least, unconventional, or so it seems.

The actors’ performances, Christopher Plummer (1963) and Joaquin Phoenix (2000), shine in portraying a complex, tormented, exuberant character, yet never entirely detestable. This, in a way, somewhat rehabilitates the man who was severely discredited by most contemporary sources, especially the Historia Augusta, a text dealing with the successive reigns of emperors between the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

The author, likely a senator from the 4th century, stands out throughout the work through the systematic use of value judgments and lascivious details, deviating considerably from the rigor demanded by historical analysis.