The Constitutio Antoniniana, promulgated in the year 212 CE, derives its name from the issuing authority, Emperor Caracalla (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus). This legislation is also referred to as the Edict of Caracalla (Antonine Constitution). It grants Roman citizenship to every free man residing within the lands of the Roman Empire. Inherited through both lineage and adoption, citizenship entails certain rights. For instance, a citizen can gain access to property, bequeath a legacy to heirs, and claim the privilege of wearing the toga. However, it also imposes specific duties, particularly of a fiscal nature.

The Constitutio Antoniniana signifies a pivotal moment in the evolution of the Roman Empire, as citizenship had hitherto been granted only to inhabitants of Italy and municipalities with the status of a Roman colony. It could also be acquired through purchase or after completing 24 years of service in the military. Despite certain adverse consequences, the Constitutio Antoniniana stands out as one of the most renowned laws of the Roman Empire, symbolizing its golden age.

—>The Constitutio Antoniniana was a significant legal reform in the Roman Empire. It marked a shift from a system based on status to one based more on geography and had profound implications for the social and economic structure of the Roman world.

Why Was the Constitutio Antoniniana Created?

Roman citizenship was initially granted to the inhabitants of Italy and later extended to Roman colonies. It could be acquired either by birth or through naturalization, with the newly minted citizen adopting the family name of the magistrate who conferred citizenship and joined their tribe. The affluent also had the option to purchase citizenship. Towards the end of the Republic, citizenship became attainable through military service, as it was systematically granted to soldiers who had served a minimum of 24 years.

The Constitutio Antoniniana (Edict of Caracalla) is complex in its origins, making it delicate to definitively establish its reasons. The likely objectives include fostering unity within the Empire and streamlining administrative processes. Its enactment contributed to the popularity of the young emperor. The rise in the number of citizens is coupled with increased tax revenues, primarily attributable to the inheritance tax.

What Does It Mean to Be a Roman Citizen?

The Roman citizenship entails fundamental rights, including:

- Right to vote

- Right to property

- Right to marriage

- Right to bequeath property to heirs

It also ensures civil rights such as:

- Ability to buy and sell within Roman territory

- Eligibility to Marry a Roman Citizen

- Permission to wear the toga and bear the tria nomina (first name -praenomen-, family name -nomen-, nickname – cognomen-)

- Capability to initiate legal proceedings in a Roman court

Citizenship comes with accompanying duties, which include:

- Participation in Census

- Contributions to occasional military expenses

- Payment of an inheritance tax

What Was the Constitutio Antoniniana?

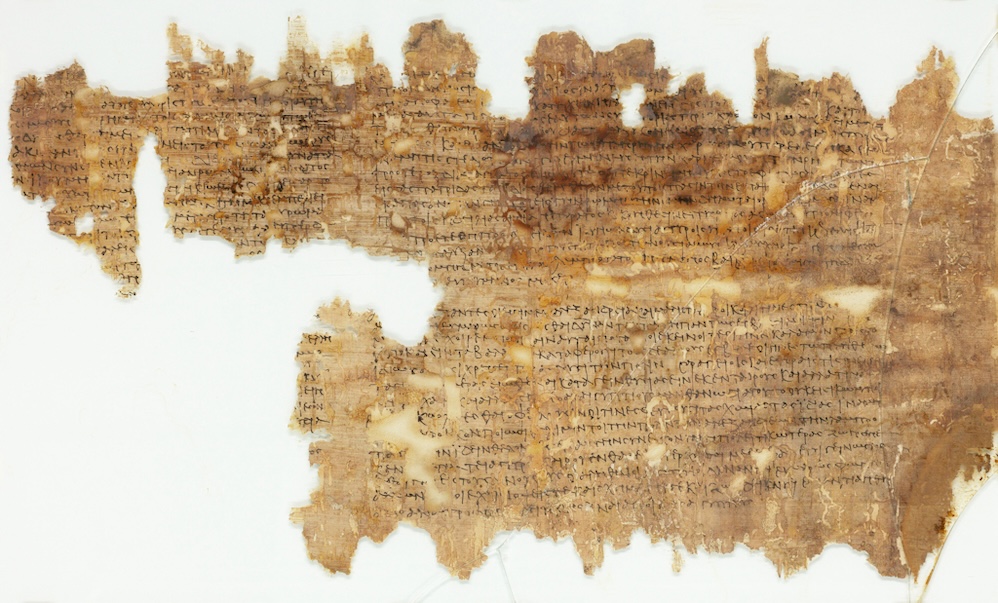

The Edict of Caracalla has long been known through references and commentaries by certain ancient authors, most of whom were not contemporaries of the events. A papyrus known as Papyrus Gissensis 40 lists three imperial decisions of Caracalla in the Greek language, but it is challenging to conclusively establish that they pertain to the Antonine Constitution.

Historians ascertain that the Edict of Caracalla proclaims: “I grant to all those in the Roman world the citizenship of the Romans.” The inhabitants, termed “peregrinus,” are free non-Roman men (foreigners). Residing in Rome or its provinces, they lack the rights of citizenship and Latin rights, exclusive to Roman citizens. Consequently, they are prohibited from marrying Roman women or participating in political life, subject to the laws of their own community.

Therefore, the Antonine Constitution confers Roman citizenship upon all free men within the Empire, effective from the day of its promulgation. They, however, retain the option to preserve their rights and customs as long as they desire. Roman citizenship is hereditary through adoption and lineage. The Edict of Caracalla has become emblematic of the golden age of the Roman Empire, now politically unified with a universal culture.

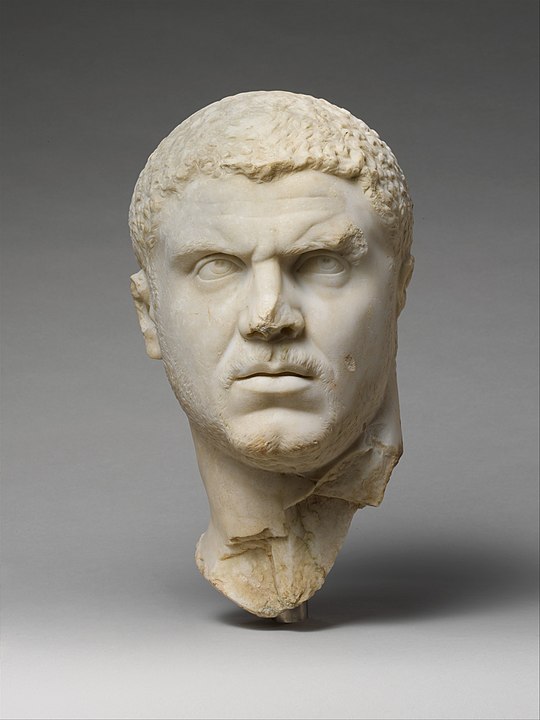

Who Was Emperor Caracalla?

Lucius Septimius Bassianus was born on April 4, 188, in the Gallic region of Lugdunum (Lyon). His origins trace back to Carthage, present-day Tunisia, on his father’s side (Septimius Severus, of Punic and Berber descent) and Syria on his mother’s side (Julia Domna). He was renamed Marcus Aurelius Antoninus in order to be closer to the prestigious Antonine dynasty, which is why the Edict of Caracalla is also called the Antonine Constitution. The epithet “Caracalla” originates from the Gallic garment with long sleeves and a hood that he commonly wore.

Upon the death of Septimius Severus in 211, Caracalla was obligated to share power with his brother Geta. Alleging a conspiracy by Geta, Caracalla orchestrated his brother’s assassination. As emperor, he delegated internal affairs to his mother, Julia Domna, while focusing on military campaigns. In 213, he engaged in various campaigns against the Alamanni. Admiring Alexander the Great, he identified with him and later waged a campaign against the Parthians. Seeking the daughter of the Parthian king for marriage, he traveled to Mesopotamia with his army and took advantage of the celebration to order an attack.

Between 215 and 216, Caracalla’s visit to Alexandria resulted in several massacres, driven by his perceived lack of respect. The intellectual elite suffered significant losses, as did a substantial portion of shippers, leading to the decline of the port. Caracalla, a military tyrant, became unpopular and was assassinated by Martialis on April 8, 217, near Harran. Macrinus, the Praetorian Prefect who succeeded him, likely orchestrated the assassination.

What Were the Positive Impacts of the Constitutio Antoniniana?

The Constitutio Antoniniana serves to enhance the popularity of the young emperor, garnering support from the provinces. It also attracts followers to the imperial cult, ultimately solidifying control over the various provinces. Instituted by Emperor Augustus, this set of rituals, prayers, and sacrifices primarily aims to cement the Pax Romana. The expansion of Roman citizenship contributed to the unity of the empire and economic development.

According to Cassius Dio, a contemporary of Caracalla known for his Roman History, this law is crucial for the glory of the Roman Empire. However, the Antonine Constitution entails new taxes: granting citizenship to a large number of individuals involves significant financial gains, especially through the inheritance tax.

The Constitutio Antoniniana additionally offers the advantage of streamlining administrative and judicial management within the Empire.

What Were the Negative Consequences of the Constitutio Antoniniana?

The Roman army’s main lure was obtaining Roman citizenship. Upon completing military service, foreigners (peregrinus) also received a substantial sum, enabling them to settle. The Edict of Caracalla (Constitutio Antoniniana) initially had a negative impact on recruitment. Consequently, the army transforms from a conquering force into a defensive one, marking what some interpret as the onset of Rome’s decline.

The Antonine Constitution swiftly endangers Roman citizens who are Christians. Refusing to partake in the Emperor’s worship or make sacrifices to the gods, persecutions intensified throughout the third century. In 250, Decius mandates obligatory sacrifices to the Roman gods under the threat of death. In 303, Diocletian’s Great Persecution became the deadliest in Africa.

The Constitutio Antoniniana accentuates the distinctions between the two categories of citizens in ancient Rome:

1. Honestiores—the honorable (the elites)

2. Humiliores—the humble (the common people)

The honestiores encompass senators, knights and their families, veterans and their children, and individuals holding or having held public offices in cities and municipalities outside Rome and their descendants. The humiliores include all other citizens. Unlike the humiliores, the honestiores cannot be subjected to torture, are subject to capital punishment only in cases of parricide or high treason (resulting in beheading), and are exempt from forced labor or mining sentences.

Featured Image: Constitutio Antoniniana in Klimavitrine, by Frank Waldschmidt-Dietz [CC BY-SA 4.0].