During the Middle Ages, Western Christians led military expeditions to the Middle East in an effort to wrest control of Jerusalem and the Holy Land away from the Muslim Ottoman Empire. This included the site of Christ’s burial. Between 1095 and 1270, there were eight major crusades. The likes of Richard the Lionheart, Frederick Barbarossa, and Philip Augustus were among the great European kings and feudal lords who made their mark. The great military epic of the Crusades was ultimately unsuccessful. These voyages to the East stoked the fires of holy war and vengeance by targeting the Muslim world, which had hitherto been tolerant of Christians. The Ottomans would eventually capitalize on these sentiments.

An overview of Crusade history

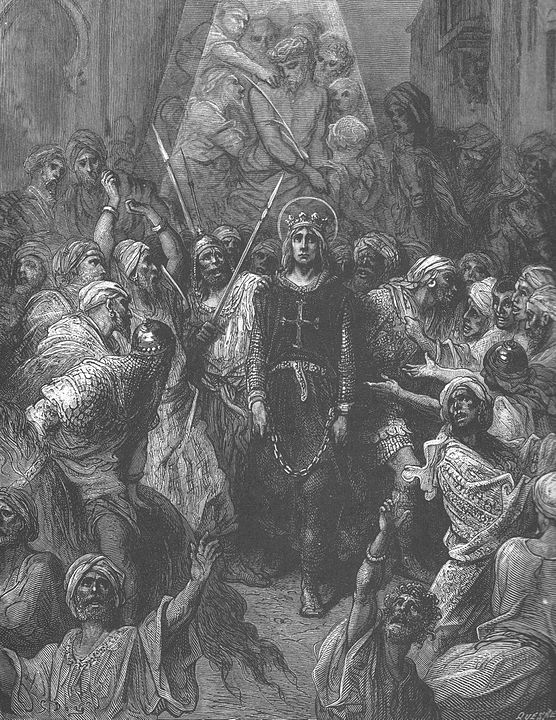

![Crusades: Expeditions to the Holy Land in 1095 and 1291 2 A crusader is shot by a Muslim warrior during the Crusades, circa 1250 [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]](https://malevus.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/crusades.webp)

In addition to being an era of incremental assertion of royal powers and the willingness of certain lords to go to war in order to gain wealth elsewhere, the Crusades were remarkable because they were an epic in their own right and took place within the greater global framework of Westward expansion. Finally, it’s the increasing influence of the Church in society that could be traced back to the Gregorian reforms, as well as the rivalry between the Church and other religious and political institutions like Byzantine Christianity and, of course, Islam.

For this reason, these “holy wars” were more than just a “clash of civilizations,” or religious conflicts, and they would continue for another two centuries.

After Roman Emperor Diogenes IV’s fall at the hands of the Seljuks of Alp Arslan in 1071, the province was firmly under the control of the Abbasid caliphate. However, the Turkomans in Anatolia and, more specifically, the Fatimid caliphate in Cairo, were formidable adversaries. Unless the Muslims can come together, the Byzantine Empire’s decline would not bring about peace. However, the battle of Manzikert had Western repercussions and was frequently seen as one of the reasons why Urban II was called to the crusade.

It was widely agreed that the Investiture Controversy, or the pinnacle of the conflict between the Germanic emperor and the pope, began at the assembly at Worms in 1076 (Synod of Worms). The second group desired autonomy in politics and, by extension, acceptance. Within the framework of the coming crusades, this was crucial.

Alfonso VI of Castile’s conquest of Toledo in 1085 marked the beginning of the Reconquista, which was commonly referred to as a “crusade” in the Western world. The rivalry between the Papacy and the Empire further worsened with the passing of the great Pope Gregory VII.

In the Battle of Sagrajas, in 1086, the Spanish army was forced to retreat during Almoravid resistance against the Reconquista.

One possible precursor to the First Crusade was the 1087 sacking of Mahdia by an alliance of Genoese, Pisans, and Normans from Sicily. An indulgence was granted to the soldiers by Pope Victor III.

After the death of Seljuk Sultan Malik Shah in 1092, Turkish expansion ceased. At the same time as the Fatimids were rising to prominence and the Byzantine Empire was becoming more stable under Alexios I Komnenos’ rule, power was being contested by rival emirs.

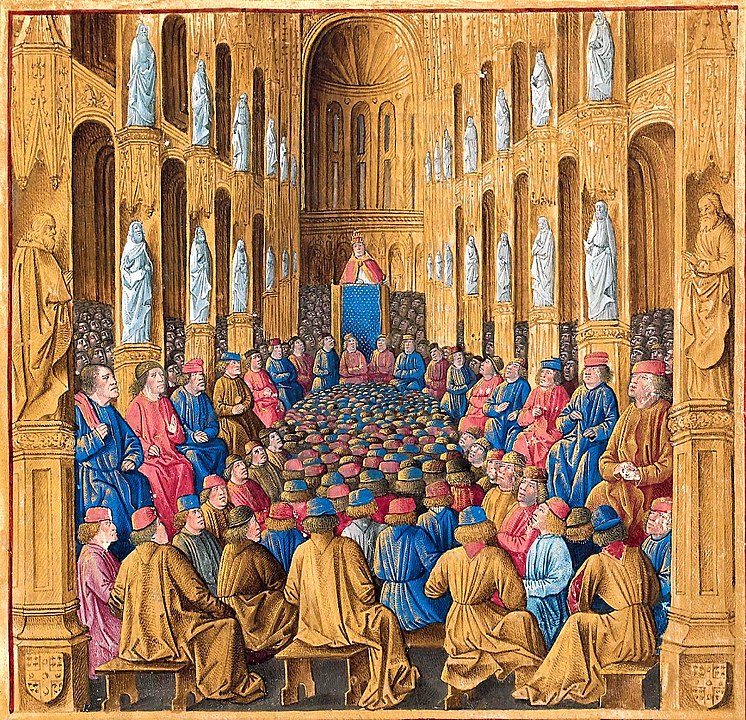

First Crusade

Pope Urban II, who was elected during the chaos of 1088 and who took control of Rome in 1093, attended the Council of Clermont to legitimize his position in the kingdom of France, whose king, Philip I, he had excommunicated. On November 27, Pope Urban II issued a call for help in freeing the Holy Places and the tomb of Christ, as well as coming to the assistance of the Eastern Christians.

He promised salvation to the pilgrims. Even if the title “First Crusade” was not used at the time, this event marked the beginning of the conflict. The so-called People’s Crusade, under the leadership of St. Peter the Hermit, took the path of central Europe, while the crusade of the nobles opted for the southern route. The capture of Constantinople was a shared goal. Ahead of the Holy City.

The Byzantines rapidly carried the People’s Crusade over the Bosphorus to the other side, where the Turks slaughtered the crusaders. This all took place in 1097, after the crusade had been publicized by the plundering and killing of Jews. After some time, the barons got it to Constantinople, where they entered into difficult discussions with Alexios I Komnenos. The Crusaders had their first successes in Anatolia.

In 1098, the Fatimids retook Jerusalem from the Seljuks. In the North, the Crusaders founded the county of Edessa and took Antioch with difficulty. They did not return it to the Byzantines as planned, provoking the anger of the Basilians.

In 1099, the crusaders successfully captured Jerusalem. On July 15, the city was captured and “purified” in blood. Even though Godfrey of Bouillon was named “Advocate of the Holy Sepulchre,” many nobles and pilgrims left for the West. It was time to start building the Latin States of the East, which would be comprised of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, and the Counties of Tripoli and Edessa.

From 1100 until 1118, Jerusalem’s first king, Baldwin I, ruled over the city. During his reign, he captured Acre (1104) and Beirut (1110), and he repelled raids from the Turks and the Fatimids. He oversaw the construction of Montreal’s iconic fortress in 1115. In addition, the monarch had to contend with rivalries within other Latin nations.

When Mawdud, the atabeg of Mosul, attacked the Latins at Harran in 1105, it was the first serious loss they had ever experienced. Baldwin II ruled Jerusalem from 1118 to 1131. Despite his best efforts, he ran into trouble and was eventually captured in 1123 while trying to carry out his predecessor’s mission.

The Crusaders suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Ager Sanguinis in 1119. This marked the beginning of difficulties for the county of Edesse.

The reign of Sultan Mahmud, 1127–1144, was marked by the appointment of a certain Zankî (or Zengi) as his atabeg. At first, this new powerful man aimed to conquer emirs like Damascus’, but he eventually turned on the Franks. By taking advantage of the Latins’ tensions with the Byzantine Empire over its claim to Antioch’s restitution, Zankî harassed the county of Edesse. In 1144, the first Latin state was wiped out when Turkish armies swiftly captured Edessa.

In 1145, Pope Eugene III issued a crusade summons and entrusted Bernard of Clairvaux with the task of preaching to the faithful. However, the volunteers were not making any significant efforts. French King Louis VII had to wait until the next year to propose while trying to convince Emperor Conrad III to join him.

Second Crusade

From 1147 until 1149, the Second Crusade’s missions faced constant peril. The Byzantines and Normans were always at odds with one another because of the island of Sicily. Baldwin III was too young to lead, and the kingdom of Jerusalem was in disarray as a result of rivalries and Queen Melisende’s influence when the crusaders came. Moreover, there were whispers of Eleanor of Aquitaine’s adultery when she was married to Louis VII. The two sovereigns of the Crusaders were unsuccessful before Damascus because of bad advice. As the year 1148 came to a close, Conrad III made the decision to return to the West, and Louis VII soon after, in the spring of 1149.

After Zanki’s assassination in 1146, the dynasty remained united until 1163. Nur ad-Din, his son, took over the fight against the amirs and the jihad against the Franks after his father’s death. With his 1149 victory over Raymond of Poitiers, he posed a serious threat to the principality of Antioch, and with his 1154 conquest of Syria, he effectively ended that threat. On the other hand, he was aware of a few problems (the loss of Ascalon in 1153, the defeat of Harim in 1157, or the failure in front of the Krak in 1163). Next, Nûr al-Dîn decided to make contact with his Fatimid adversaries.

Amaury I of Jerusalem was king from 1163 until 1174. Egypt was his fixation. He made several unsuccessful attempts to invade it. In his final attempt, he perished as Nur ad-Din and Saladin both posed threats to the kingdom of Jerusalem from the north and south, respectively.

Nur ad-Din tasked Shirkuh with conquering Egypt between 1164 and 1174, and the latter did so with the help of his nephew Saladin. In 1169, he was appointed vizier and began openly challenging Nur ad-Din. After his death in 1174, Saladin rallied the Muslim faithful to resume the holy war (jihad) and retake the holy city of Jerusalem.

Baldwin IV of Jerusalem ruled from 1174 until 1185. After the “Leper” king defeated Saladin at Montgisard (1177), he made valiant attempts to repel further attacks. Despite his relative success in handling the Raynald of Châtillon issue, he was unable to stop his sister Sibylle and her husband Guy of Lusignan from seizing the throne after his death and the brief reign of his nephew.

Saladin spent the years 1174-1187 battling the Franks and subduing the Zengid. By the mid-1180s, he had successfully rallied the Muslim world under his banner, deposed the Fatimid Caliph of Egypt, and begun the jihad to capture Jerusalem. Using the internal strife of the Latin realm to his advantage, he defeated the Crusaders at Hattîn (Battle of Hattin – July 1187) and captured King Guy of Lusignan. He marched into Jerusalem in triumph on October 2, 1187.

Frederick Barbarossa, Emperor of Germany, consolidated his power with the Peace of Constance (1183), which was signed between 1183 and 1188. In 1188, with the Empire at peace, he made the decision to take up the cross at the Diet of Mainz.

Western Europe was embroiled in a civil war between King Henry and his son Richard, both members of the Plantagenet dynasty, in 1186 and 1189. France’s King Philip II Augustus backed the latter. After becoming king of England in July 1189, Richard the Lionheart followed in his father’s crusade footsteps.

Third Crusade

After hearing the shocking news of Jerusalem’s reconquest by Saladin in 1187, Pope Gregory VIII and his successor, Stephen III, called for the Third Crusade. The conflict between Philip Augustus and Richard the Lionheart erupted during their halt in Sicily in 1190, and the two leaders ended up leaving together. Frederick Barbarossa died in the same year, in June, when he was swept away by the waters of the Goksu River, Turkey. Richard the Lionheart captured Acre with the King of France in 1191 and then fought Saladin at Arsuf in September.

While all this was going on, Philip Augustus went back to his country. In 1192, the English monarch, still hesitant to approach Jerusalem, and an increasingly frail Saladin continued their war. Richard signed a treaty with the Sultan and went back to the West, where John and Philip had taken advantage of the situation in his absence.

In 1193, Saladin passed away. There was a time of immense discord in the Ayyubid Empire.

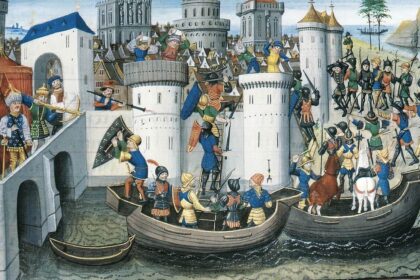

Fourth Crusade

Richard the Lionhearted and Saladin made peace treaties in 1198 and 1204, but Pope Innocent III had no intention of honoring them. He instead called for a new crusade. But the crusaders had trouble organizing the fourth crusade and turn to Venice for help. The crusade was redirected by Enrico Dandolo, first to Zara in 1202, and then to Constantinople, where it encountered internal strife once more. On April 13, 1204, the “second Rome” was taken and pillaged, the Byzantine empire was broken up, and the divorce between Catholics and Orthodox was finalized.

The difference occurred in the Holy Land between the years 1204 and 1211. There had been splits within each camp. The Western Christian military leadership was pressing for a break in the truce and a rise in attacks on enemy territory for any reason. Saladin’s heirs were fighting amongst themselves, diminishing the empire the Sultan had built just as trouble was brewing in the East.

Between 1206 and 1207, the Mongols under Genghis Khan conquered Asia. The Crusade against the Albigensians began in 1209. For modern Western monarchies, the East was no longer a top concern.

The 1212 Children’s Crusade was remarkable because it was one of the first and most novel military excursions of its kind. Young people in France and the Empire caught up in a spiritual fervor and determined to make their way to Jerusalem. In the end, most of them were captured or sold into slavery, but the crusade’s fervor was reignited for a while. In the same year, the Spanish won a major victory at Las Navas de Tolosa against the Almohads, marking the beginning of the unstoppable progress of the Reconquista.

Fifth Crusade

From 1213 to 1221, Innocent III does everything he can to fix the mess that was the Fourth Crusade. In 1213, he called a meeting in Lateran. Again, not many people signed up to fight in a war between France, England, and the Empire (Battle of Bouvines, 1214). Innocent III died in 1216, and Honorius III, who took over after him, started the appeal all over again. The Emperor Frederick II was not wanted, so Leopold VI of Austria led the Fifth Crusade, which was again led by someone who was not a major ruler. In 1219, the Crusaders took the Egyptian city of Damietta by taking advantage of differences among the Muslims. But because they were too far away, they had to give up their conquest in 1221.

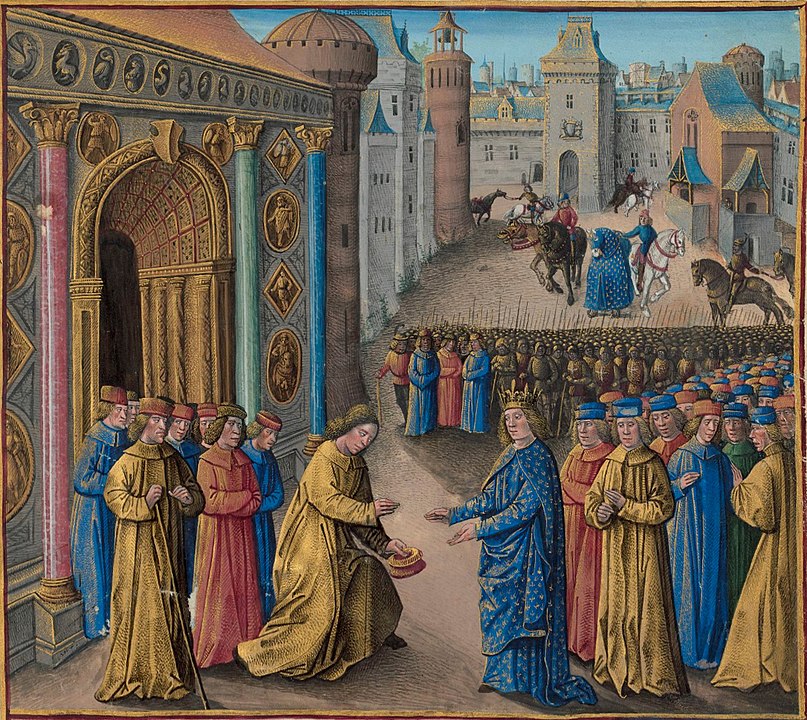

Sixth Crusade

Frederick II, who became Emperor in 1215 under the efforts of the Pope, repeatedly delayed his departure for the Crusades. At long last, in 1227, he was excommunicated by Pope Gregory IX. The year after his return, Frederick II traveled to the Holy Land, where he was met with the hatred of all the military orders saved the Teutons in the middle of baronial conflicts. In order to regain Jerusalem, he deftly used the Ayyubids’ vulnerabilities to negotiate a contract with them, which was signed on February 18, 1229, in Jaffa. In March, he would make the trek and get his crown before returning to the West.

In 1239–1240, Pope Gregory IX sent Thibaud IV, Count of Champagne. Both the orders and the followers of the Germanic Emperor Frederick were more hostile, and tensions also rose between the Franks and the Syrians.

When the Mongols invaded Anatolia in 1243, they were able to defeat the Seljuks at Köse Dağ. On August 23, 1244, Sultan al-Salih employed the Khwarezmians—who were themselves on the run from the Mongols—to reclaim Jerusalem. The majority of the Frankish army was annihilated on October 17 of that year. The king of France, Louis IX, decided to take the cross himself.

Seventh Crusade

From 1248 to 1254, Louis IX led a crusade that set sail from Aigues-Mortes, arrived in Egypt, and eventually captured the city of Damietta. The next year, however, the Mamluk Baybars destroyed the crusader force in the Battle of Mansurah, and Louis IX was captured. Damietta was the price he paid to be released from a demanding ransom. He left for the Latin States and stayed there until the year 1254.

After killing Turân Shah in 1250, the Mamluks seized control of Egypt. Syria remained in Ayyubid hands. Moving on, in the years 1256–1264, the fight for power in the eastern Mediterranean reached a fever pitch, with the Latin nobles, Templars, and Hospitallers joined by the Italian towns of Genoa and Venice. The cities of Tyre and Acre were at risk in this conflict known as the War of Saint-Sabas (after a monastery in Acre).

In 1258, the Abbasid caliph was beheaded by the Mongols after they destroyed Baghdad. Then, the Mamluks defeated the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut and subsequently conquered Ayyubid Syria in 1259.

Baybars ruled the Mamluks from 1260-1271. Caesarea, Arsuf, and most notably Antioch (1268), as well as Krak, were among the cities he captured from the Franks (1271). In the meantime, in 1261, the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos retook Constantinople from the Latins. Charles I of Anjou became king of Sicily in 1266. In 1267, Louis IX re-accepted the Cross.

Eighth Crusade

The King of France launched an invasion of Tunisia in 1270 on the advice of his brother Charles of Anjou. However, sickness swept across the crusader camp on August 25, shortly after Louis IX had passed away from complications related to the siege of Tunis.

In 1272, Prince Edward of England, Louis IX’s reinforcement, arrived in the Holy Land and made a few fruitless raids. He quickly turned back. With Baybars’s demise in 1277, the Latins finally got a break. After that, Charles of Anjou was anointed King of Jerusalem in 1278.

As late as 1282–1285, the Angevins ran into problems with the Italians due to the effects of the Sicilian Vespers. Acre and Tripoli renewed their fight. Qalawûn, sultan of the Mamluks, used this to his advantage and conquered them in 1289.

After a five-week siege, al-Ashraf Khalil, Qalawun’s successor, conquered Saint John of Acre in 1291. The last of the Latin states in the Holy Land collapsed. Despite the animosity that was stoked by the crusades, trade and cultural contacts between Christians and Muslims flourished.

TIMELINE OF THE CRUSADES

August 19, 1071: The defeat of the Byzantines at Manzikert

Roman IV Diogenes, emperor of Byzantium, was soundly defeated by the Seljuks. Near the Turkish lake of Van, he attempted to retake the citadel of Manzikert. Due to this setback, Asia Minor was effectively conquered by Turkish forces. When the Seljuks conquered Jerusalem seven years later, it became more difficult for Christians to make the trek there. Without a doubt, this was one of the primary motivations for the initiation of the First Crusade in 1095.

November 27, 1095: The pope launches the first crusade

Pope Urban II encouraged the Western kings’ knights to go on a crusade at the Council of Clermont. The objective was to conquer Jerusalem and free the Holy Land. At the close of summer 1096, under Godefroy de Bouillon of Lorraine’s leadership, the first crusaders set sail.

August 1096: The People’s Crusade arrives in Constantinople

Peter the Hermit and Walter Sans Avoir led a band of People’s Crusade to the gates of Constantinople. In response to Pope Urban II’s invitation, the People’s Crusade resolved to begin their journey to the Holy Land the next day. Pilgrims traveled throughout Europe, with some destroying Jewish neighborhoods and cities along the route. In the end, Peter the Hermit and his army made it to the Near East by way of the Bosphorus, with the assistance of the Byzantines. A few months later, however, the Turks would wipe out the remaining 12,000 Crusaders who had continued on their expedition.

June 3, 1098: Antioch was taken by the crusaders

Noble crusaders, answering Pope Urban II’s appeal, conquered Antioch and later Syria. Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemond I, Count of Toulouse, and Adhémar of Monteil, papal legate, commanded the Crusader forces. After successfully retaking Nicaea the year before, they were ultimately obliged to cede it back to the Byzantine Empire after reaching a deal with Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. In the years that followed, they were able to conquer most of the Middle East, including Jerusalem in 1099, thanks to a decisive victory against the Turks in Asia Minor.

July 15, 1099: The Crusaders take Jerusalem

After leaving France at Pope Urban II’s request in 1096, the Crusaders under Godfrey of Bouillon and the Count of Toulouse arrived in Jerusalem. Both Muslim and Jewish city guards were slaughtered. Nearly 100,000 people perished when the Holy City was taken. In this way, the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem was established. As the avenger of the Holy Sepulchre, Godfrey of Bouillon assumed control of the city government.

February 15, 1113: The Hospitaller order was recognized

The Order of the Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem was established and acknowledged by Pope Paschal II shortly after the Crusaders’ conquest of Jerusalem. In its early days, the order was little more than a modest hospital established in Jerusalem to care for travelers who fell ill or were wounded along the way. The religious community that had been managing the establishment until then was now responsible for defending the Holy City and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The magnificent Tripolitan citadel, the Krak des Chevaliers (also called Hisn al-Akra), fell to them in 1142. After the failure of the previous crusade, the order’s knights fled to Cyprus, where they eventually took control of Rhodes. Their moniker was the Knights of Rhodes. Once again, they were known as “Knights of Malta,” as Charles V bestowed the island of Malta on them.

January 13, 1128: The Order of the Templars was approved

The Council of Troyes approved the rule of the Order of the Knights Templar. This was how the order was officially recognized. Hugues de Payens, a knight, had established it 10 years previously. King Baldwin II of Jerusalem had provided shelter for the knights in the old Temple of Solomon, hence the origin of their name. Their job was to keep the pilgrims safe. The Templars, also known as the “Order of the Temple,” expanded in both wealth and influence. In 1307, Philip the Fair arrested the Templars.

December 1145: The Pope calls for a second crusade

The Christian kingdom of Jerusalem lost Edessa to the Atabegs of Mosul in 1144, after the latter’s conquest left the former weaker due to internal strife. Pope Eugene III was motivated by this occurrence to issue a call for a new crusade, despite the fact that few Christians were interested in participating.

October 2, 1187: Saladin takes Jerusalem

The reconquest of former Crusader territory had been going on for months, with Sultan Saladin leading the charge. He took Jerusalem in 1187, providing Pope Gregory VIII with an excuse to launch another crusade to the Holy Land.

October 29, 1187: Call to the Third Crusade

A massive army headed by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, King Richard I of England, and King Philip Augustus of France embarked on the Third Crusade. But things went wrong for the Christians. Before anything else, know that Barbarossa passed away in the year 1190. When St. John of Acre was captured, Philip Augustus headed back to France. Richard the Lionheart, left on his own, lacked the resources to recover Jerusalem and so made a quick peace with Saladin before fleeing to England.

January 1192: Richard I of England renounces Jerusalem

Richard the Lionheart was unable to retake Jerusalem because he lacked the support of the German emperor and the king of France. Richard I agreed with Saladin and abandoned plans to capture Jerusalem since England needed a monarch. He succeeded in having the Sultan allow Christian pilgrims entry to the Holy City. This ensured three years of tranquility.

July 17, 1203: The Crusaders take the Byzantine city of Constantinople

Some knights, hearing Pope Innocent III’s call to arms in 1202, set out on the Crusades’ path to Egypt. The Venetians only promised to pay for the knights’ sea travel if they captured the city of Zara in Dalmatia. Everyone therefore focused their efforts on putting Isaac II Angelos, back on the Byzantine throne rather than retaking the Holy Land. The Venetians were excommunicated by the pope, but it didn’t stop the crusaders from assaulting other Christians. A few months later, they retook the city and looted it again on their way to founding the Latin Empire in the East.

1212: A crowd of children goes on crusade

Many needy people, including children, assemble in Cologne at the instigation of a young man named Nicolas in the hopes of embarking on a crusade to save the Holy Land. A certain Stephen in France likewise said he had a revelation from Christ, spreading the movement from Germany to that country. A large group of individuals, estimated to number in the thousands, left for Jerusalem and the Holy Sepulchre. Few of them would ever come back. Not all of them would make it, however; some would perish on the way, and the rest would be sold into slavery.

November 30, 1215: Fourth Council of the Lateran

Under Pope Innocent III’s leadership, the Fourth Lateran Ecumenical Council forbids the establishment of any new religious organizations. It called for a fresh crusade and criticized the Cathars and Waldensians.

February 11, 1229: Frederick II signs the Treaty of Jaffa

Following his departure on crusade the year before, Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen reached an arrangement with Sultan Malik el-Kamil. Therefore, he was able to reclaim the holy cities of Bethlehem, Nazareth, Sidon, and Jerusalem. Frederick II was eventually proclaimed king of Jerusalem, and peace lasted for a number of years under his rule. But his irreverence will not be tolerated, and he will soon return to his homeland. In 1244, the Turks recaptured Jerusalem.

June 6, 1249: Saint Louis takes Damietta

St. Louis, King of France, led the Seventh Crusade and captured the city of Damietta. The king’s army took heart from this success, and they went on to beat the Mamluks decisively at Mansûrah. Sadly, the epidemic was too much for it. Muslims used this opportunity to grab the remaining citizens and the monarch.

April 6, 1250: Saint Louis was taken prisoner

Louis IX and his troops were forced to deal with a plague outbreak when they took Damietta. They were badly outnumbered and eventually capitulated. St. Louis had agreed to pay Sultan Turanshâh a ransom of 400,000 pounds in exchange for his release. Also, he had to give up Damietta. On May 6th, 1250, the French king was released.

September 7, 1254: Saint Louis returned from the crusade

Louis IX, who had been away from his realm for six years, returns from the Holy Land feeling like a failure after the Seventh Crusade. Before he chooses to embark on a crusade once again in 1270, he will focus on reforming his realm.

July 25, 1261: Michael VIII Palaiologos takes Constantinople to the crusaders

Constantinople, the then-capital of the crusader-founded Latin Empire of the East, fell to Michael VIII Palaiologos’s army with little resistance. The city had been ravaged and stripped of almost everything of its value over the course of many years. Finding the ancient Byzantine capital’s previous radiation and power was challenging in this scenario. Despite being declared emperor and establishing the Palaiologos dynasty, Michael VIII will be unable to halt the city’s collapse.

August 25, 1270: Saint-Louis dies in Tunis

In 1244, when he was 56 years old, Louis IX embarked on a crusade to Tunis. The King of France passed away after a brief illness, marking the end of the eighth and last crusade.

May 28, 1291: Crusaders lose the Holy Land

Following the fall of St. John of Acre, all Crusader-held territory in the Holy Land was conquered by Muslims (now Akko, a fishing port in Israel). By 1104 the Crusaders had captured the city and given it to King Baldwin I. Despite the best efforts of the Templars and the Knights of the Hospital, the city was eventually taken by the Mamluks under al-Ashraf Khalil after a lengthy siege.

Bibliography:

- Housley, Norman (1995). “The Crusading Movement 1271-1700”. In Riley-Smith, Jonathan (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of The Crusades. Oxford University Press. pp. 260–294. ISBN 9780192854285.

- Jotischky, Andrew (2004). Crusading and the Crusader States. Pearson Longman. ISBN 9781351983921.

- Small, R. C. (1995). Crusading Warfare, 1097–1193. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521458382.

- Stevenson, William Barron (1907). Crusaders in the East. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780790559735.

- Runciman, Steven (1954). A History of the Crusades, Volume Three: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521347723.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1969). A History of the Crusades. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Murray, Alan V. (2009). “Participants in the third crusade”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/98218.