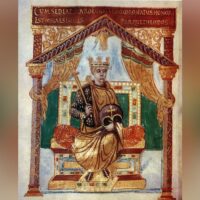

Dagobert I, the most famous Merovingian king after Clovis, reigned from 632 to 639. With the support of brilliant advisors (including Saint Eloi), he restored the unity of the Frankish kingdom during his brief yet prosperous reign and established his capital in Paris. Nicknamed the “good King Dagobert,” he held a court that his contemporaries considered lavish. After his death, the Merovingian monarchy steadily declined. Dagobert I was the first to be buried, according to his wishes, at the Abbey of Saint Denis near Paris. After him, many French kings would be interred there.

Dagobert I, the Last Great Merovingian King

Born around 604, Dagobert was the son of Clotaire II and Bertrude. At the age of ten, his father gave him the kingdom of Austrasia to satisfy the local aristocracy, which was dominated by the mayor of the palace, Pepin of Landen, and the Bishop of Metz, Arnulf. Upon his father Clotaire II’s death in 629, Dagobert was recognized as King of Neustria, although without Aquitaine, which he annexed following the death of his younger brother Caribert in 632.

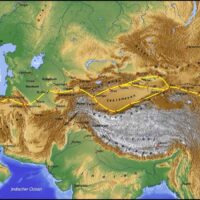

He subdued the Bretons to the west and the rebellious Gascons in the south who opposed Frankish rule. Beyond the Rhine, he made the Thuringians, Alamanni, and Bavarians tributaries and waged war against the Veneti, who lived in the Danube Valley. In 631, he concluded a peace treaty with the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius.

As the sole ruler of the Regnum Francorum (Kingdom of the Franks), Dagobert defended the kingdom’s threatened borders. He often stayed in the town of Clichy, near Paris, displaying a luxury worthy of a Roman emperor.

He traveled through the provinces, dispensing justice and instilling fear among the leudes (Frankish nobles). Like his predecessors, he had to negotiate with the demands of the Austrasian aristocracy, making his infant son Sigebert king (634).

To prevent Sigebert from one day claiming the entire kingdom, Dagobert assigned Burgundy and Neustria to his third son, Clovis II, during his lifetime.

The “Good King Dagobert”

Contrary to the implication of the song “The Good King Dagobert,” the king was not a fool. During the ten years of his reign, Dagobert wielded absolute power.

He surrounded himself with skilled advisors, including the future Saint Eloi and Saint Ouen, the latter being the Bishop of Rouen and the former a goldsmith.

The bad reputation that the song gave to the king stems from its relatively recent creation, though it predates 1789, and its subsequent adaptations. Revived in 1814, during the restoration of the monarchy, it was interspersed with contemporary satirical verses. Dagobert was part of a new generation of Merovingians more comfortable in councils than on the battlefield.

A Reign Without Lasting Legacy

A great eater, drinker, and lover, Dagobert’s health began to deteriorate in his thirties. In 636, after a near-death experience, he summoned the principal dignitaries of the Regnum and his two sons and gave them a speech: “Thus, examining my conscience and the sins of my heart, meditating on the account I must give to the sovereign King, I feared His judgment…” He increased donations to monasteries, entrusted the education of Clovis to Eloi, and reiterated the division of his kingdom: Austrasia, Aquitaine, and Provence to Sigebert; Neustria, with the Duchy of Dentelin and Burgundy, to Clovis.

Two years later, nearing death, he had himself transported to the Abbey of Saint-Denis, which he had founded, asking to be buried there. He appointed Duke Éga as regent of the kingdom with the agreement of Queen Nanthilde, and died on January 19, 639. After his death, the Merovingian dynasty continued to decline under child kings, known as “lazy kings,” who left power in the hands of factions and the mayors of the palace.