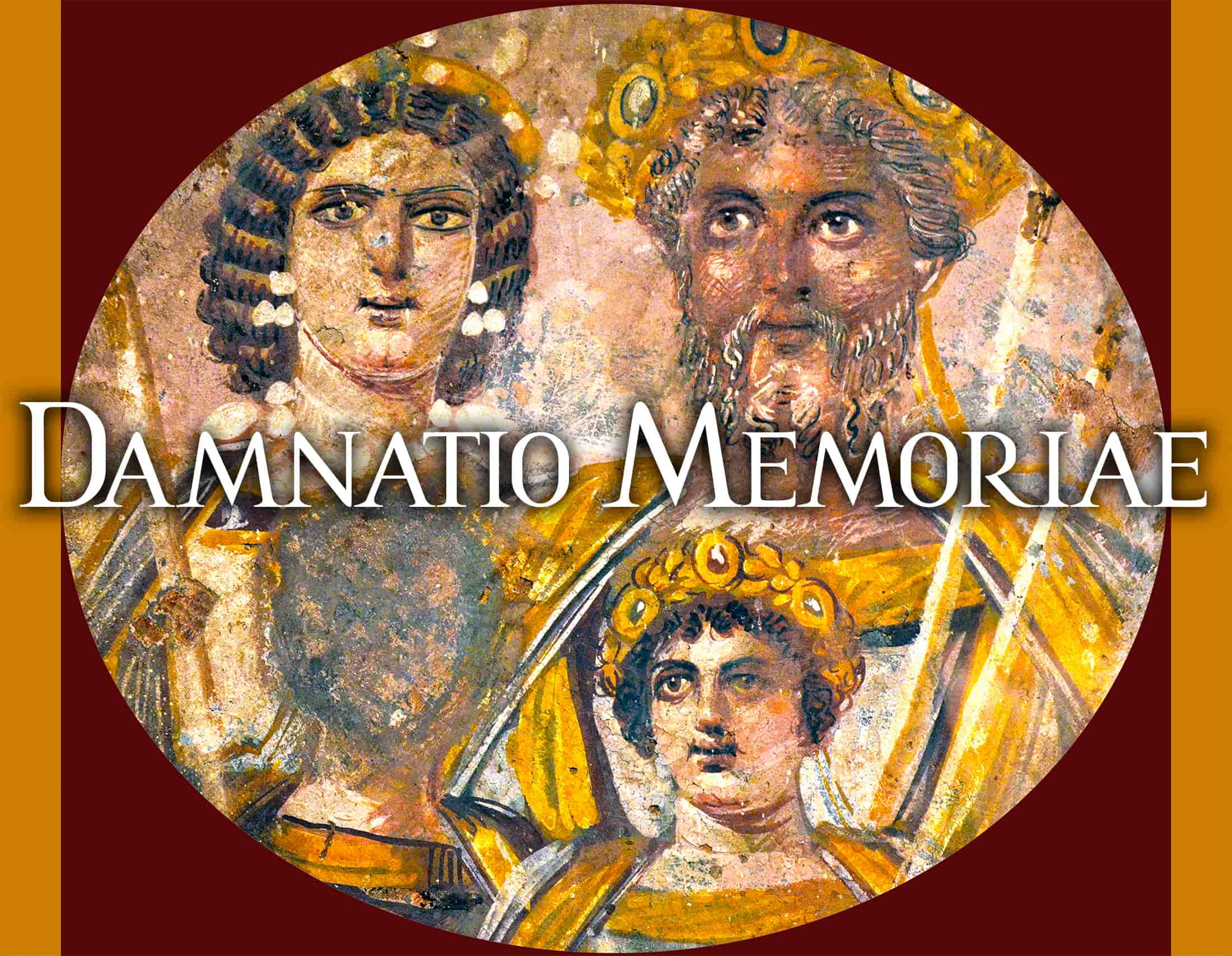

Damnatio Memoriae: Erasing History in Ancient Rome

Damnatio memoriae is a Latin phrase that translates to "condemnation of memory" or "damnation of memory." It refers to a practice in ancient Rome where the memory or legacy of a person, typically a disgraced public figure or a traitor, was intentionally erased from official records, inscriptions, monuments, and other forms of historical documentation.