Bear and Bull Baiting

This sport looked like this: take a bull or a bear, as well as a fighting dog (or better, several) on a short leash, and try to kill one animal with the other. It’s that simple.

There were many variations of this entertainment. For example, the unfortunate animal could be placed in a pit or chained to a post, so spectators could enjoy the show from a relatively safe distance. Bets were placed on how long the beast would last and how many dogs it would tear apart and trample before they finally brought it down.

However, it was far more exciting to unleash enraged bulls and bears from their chains in a field or a wide enclosure, giving the participants with their dogs a chance to chase them. A thrilling workout for both the owners and their loyal mastiffs—far more interesting than football or hockey, don’t you think?

Initially, the idea was to make the bull or bear meat more tender before cooking. But tenderizing an entire carcass with a hammer is inconvenient, while setting dogs on it is quite practical.

Naturally, this blood sport was dangerous, and not just for the dogs. First, the hunters often died or were injured by getting too close to the wild beast. Second, even the spectators were not immune from mishaps.

For example, in 1583, during a baiting event at Paris Garden in London, an excited crowd accidentally collapsed the arena, and several dozen visitors were trapped under the debris. Then, they got to know the bear a bit more closely than they had planned, and for many, the encounter was fatal. English Puritans saw this as divine wrath but believed it was due not to cruelty to animals, but because the games were held on a Sunday.

This entertainment appeared in England during the Middle Ages and remained popular until 1835. Then, the British peers decided that cruelty to animals was somewhat unbecoming and banned bull baiting, cockfighting, and other such antics. Before that, even Queen Victoria had taken part in these competitions.

English Football Without Rules

What happens if you give a crowd of rugged medieval men a ball made from a pig’s bladder stuffed with peas—heavy and hard as a stone? That’s right, you get traditional English football.

It was usually played during Shrovetide, just before Lent. The goal was simple: get the ball into the opponent’s goal by any means necessary. Sometimes, the goals were several kilometers apart. At times, they didn’t bother with constructing goals at all—in such cases, one had to throw the ball onto the balcony of the opponent’s church.

The rules did not prohibit beating opponents to take the ball, nor did they forbid causing them serious injuries and fractures. Naturally, there was no protective gear. You could even trample opponents who were lying down.

It goes further—there are mentions that participants brought knives to some matches. Why not?

There were no enclosed fields—the ball was chased through city streets, marketplaces, and agricultural fields, causing considerable material damage to unwitting spectators. Sometimes, the number of players on a team reached a hundred. Chroniclers mentioned that many footballers ended up with broken arms and legs, knocked-out teeth and eyes, and fatal outcomes were not uncommon.

This game was rightly considered incredibly dangerous, and some kings even enacted laws banning football. For instance, Henry VIII was an avid player in his youth. However, later, when he realized the damage caused to royal property by overzealous football fans, he called the sport a “plebeian game” and banned it in 1548 under the threat of death.

However, the severity of the law was mitigated by its lax enforcement: footballers continued to play, sheriffs turned a blind eye, and by 1603, the ban was lifted.

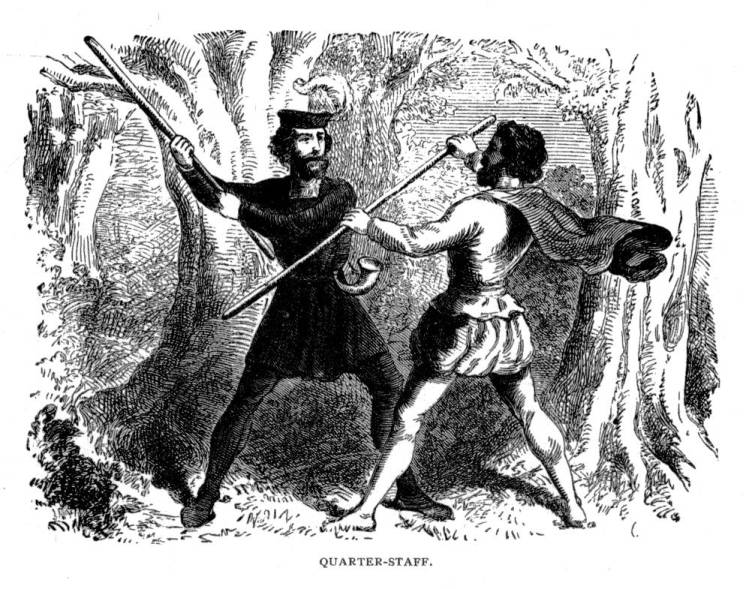

Irish Stick Fighting Tournaments

The shillelagh (from the Gaelic s iúil éille—”oak club”) is a traditional weapon in Ireland, also used as a cane. To make one, you need to trim a sturdy oak branch, carve beautiful traditional patterns on it, and then bury it in a pile of manure or put it in a chimney for several months to make the stick black and shiny.

The ancient Celts regularly held competitions in fencing with such clubs, and in the Middle Ages, the English and Irish continued this tradition. The game had clear rules—this was not a drunken brawl.

Stick fights were not only a form of entertainment but also a standard legal method for settling disputes among tenants.

Usually, the rules required knocking the opponent to the ground and dragging them along the ground for the judges to count it as a win. Often, fencing with shillelaghs led to serious injuries.

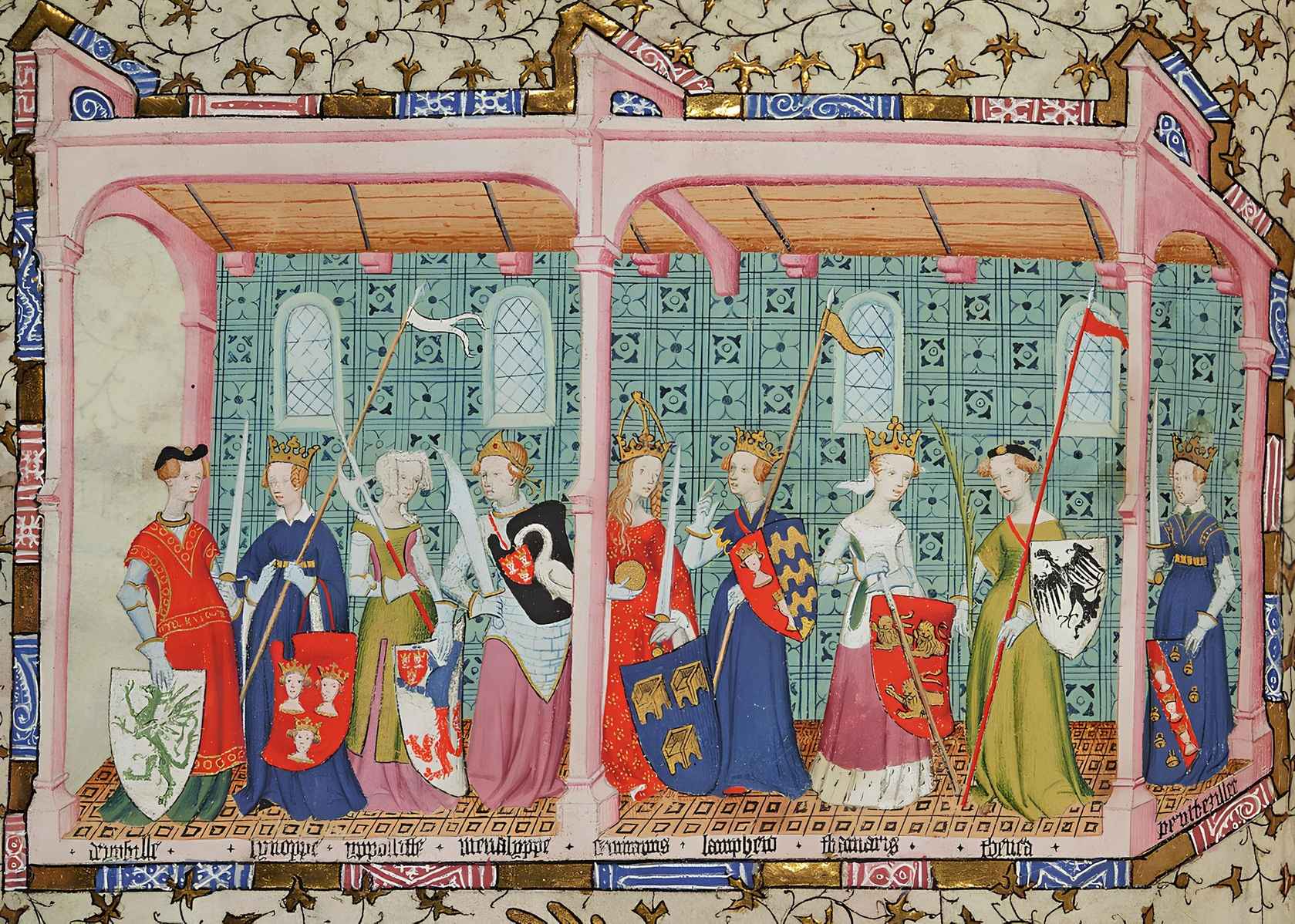

Interestingly, women were allowed to participate in the tournaments. However, men were forbidden from hitting them—they could only strike the shillelagh in the woman’s hand. The woman, on the other hand, could strike her opponent however she wanted.

And who says that women were oppressed in the Middle Ages?

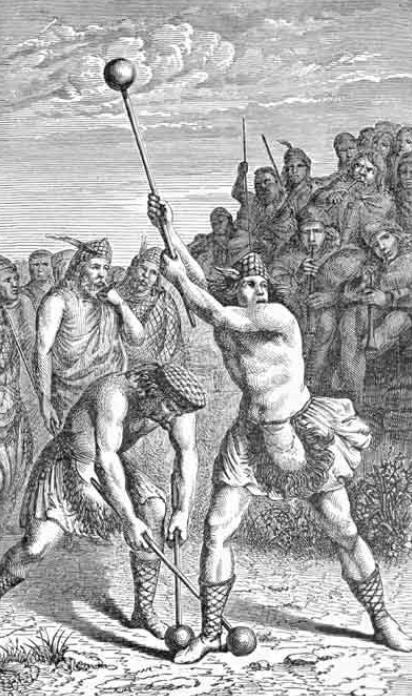

Hammer Throwing

Another sport with ancient Celtic roots is hammer throwing. The Celts engaged in hammer throwing as early as 1600 BC during the so-called Tailteann Games. These were athletic competitions that included jumping, running, javelin throwing, hammer throwing, boxing, fencing, archery, wrestling, swimming, and horseback riding.

Much like the Olympic Games, you might say. But the Tailteann Games were held at funerals.

Yes, the stern Celts believed that when an important figure like a king or military leader died, simply throwing them on a funeral pyre was too dull. So, they organized three-day feasts and competitions like hammer throwing, boxing, and vaulting. The Celts generally believed that funerals were a cause for celebration, not mourning, as the deceased was going to a better place.

Over time, the Tailteann Games were forgotten, but hammer throwing remained, becoming a popular sport in medieval England. In principle, anything could be thrown—Irish people, for example, used heavy cartwheels.

Medieval hammer throwing was a rather dangerous sport because, at fairs where it was held, there were no barriers or protection for either athletes or spectators.

Therefore, when an athlete missed the target and the projectile flew into the crowd, casualties were inevitable. But then again, what is sport without risk?

Water Jousting

Everyone knows about knightly tournaments. Two strong men in heavy armor mount their horses, take blunted lances, and charge at each other at full speed. Whoever remains in the saddle after the collision is the winner. The rules are simple—no mistake possible.

But doesn’t riding horses seem a bit dull? Isn’t it far more interesting to hold tournaments… on boats?

These jousts were invented in France—the first mentions date back to a tournament in Lyon on June 2, 1177. The mechanism of the duel is as follows: take two boats, fill them with teams of rowers. On the boats, set up simple ladders on which the knights should stand.

The boats are launched into the water—full speed ahead! The knight who knocks his opponent off the ladder wins.

Despite the seemingly comical nature of this competition, it was quite dangerous. Due to the armor, falling into the water could be fatal—25 kilograms of steel does not add to buoyancy.

Also, clashing with a single shield could result in serious injuries.

Boat jousting remains quite popular in France. Modern athletes, following in their ancestors’ footsteps, regularly hold traditional competitions in communes such as Cognac, Merville, and other places.