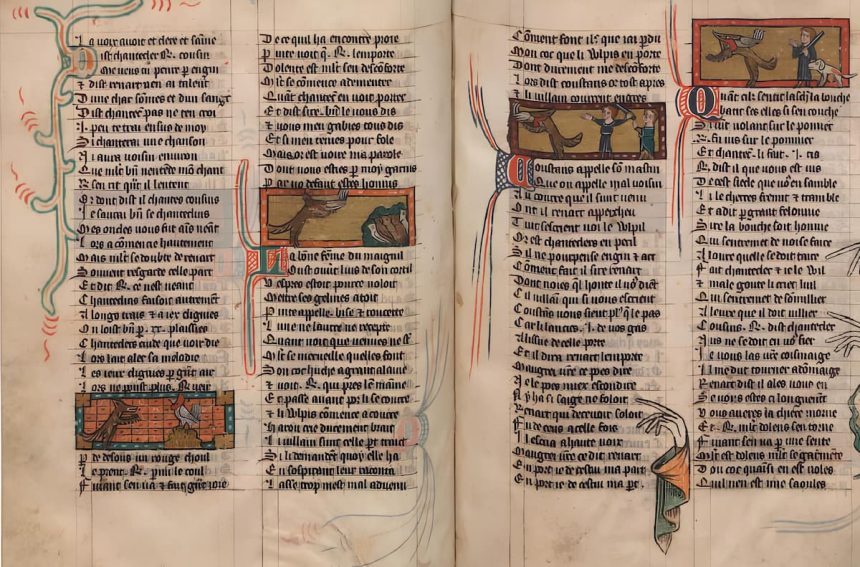

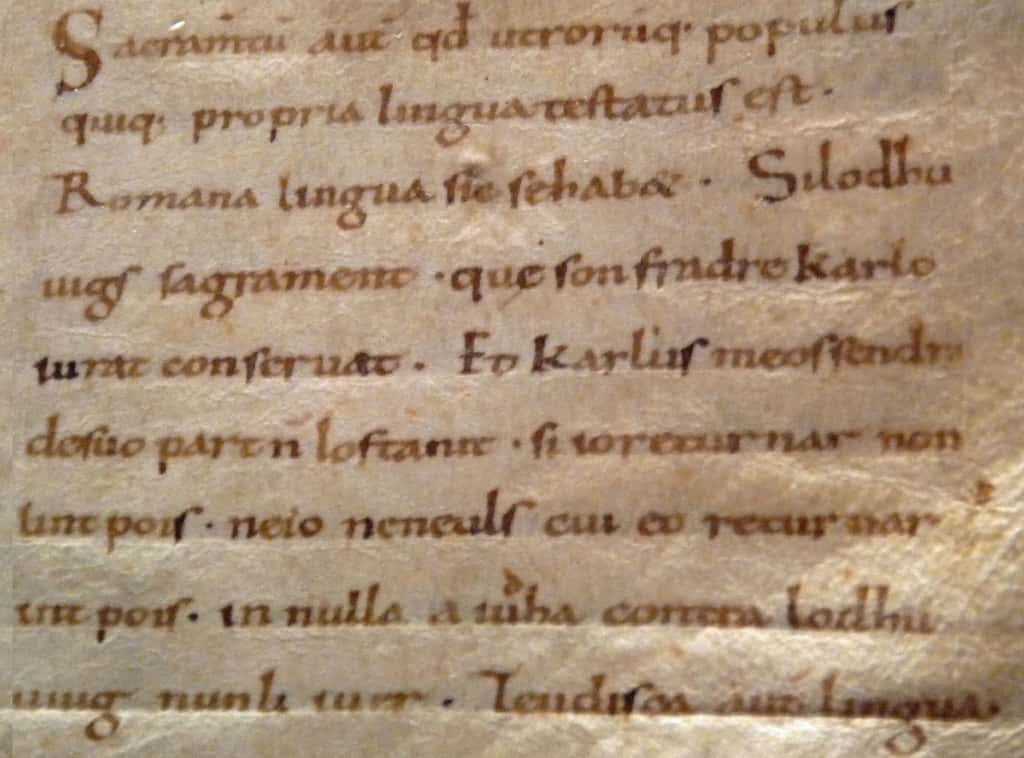

The existence of the Oaths of Strasbourg in 842, which are mutual assistance oaths between Charlemagne‘s grandsons (a bilingual document in the Gallo-Roman language, the “ancestor” of French, and in Old German), is not sufficient to identify the beginnings of the use of French in administrative documents and political acts. The use of the language must correspond to a common practice that can be observed if the state of the archives allows it.

The Emergence of Vernacular Languages

Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

A distinction must be made within the vernacular languages (local languages spoken by the community) derived from Latin, between Romance languages and those belonging to other linguistic families (Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic). As long as the link between Romance dialects and the Latin mother tongue remains, Latin continues to be used in writing. Non-Romance languages, autonomous from Latin, appear in charters (written administrative and legal acts) earlier, particularly in non-Romanized territories (Scandinavia, Central Europe, etc.).

Throughout medieval Western Europe, the primary language of charters remained Latin, which accompanied the spread of Christianity. The Latin language, liturgical and scholarly, was essentially used for establishing legal acts involving ecclesiastics. Vernacular languages penetrated charters in two different ways: first, through the clear replacement of Latin by another language, with acts written entirely in the vernacular. This almost immediate transition seems to have been the case for French. Alternatively, a vernacular language could be inserted through words and then sentences in acts written in Latin.

Langue d’oïl and Langue d’oc

The linguistic border between langue d’oc and langue d’oïl separates the regions where Occitan languages (or Occitano-Romance languages) are spoken from those where langues d’oïl (Gallo-Romance languages) are used. This transitional space is a contact zone between oc and oïl dialects, embodied in dialects influenced by each linguistic domain. The Occitan language has been spoken since around the 8th century by a population occupying a space delimited by the Atlantic and the Po Valley on one hand and by the north of the Massif Central and the Pyrenees on the other.

Provinces and later regions share this highly diversified linguistic space, which includes the following variants: Old Occitan, Aranese, Auvergnat, Béarnais, Gascon, Gavot, Limousin, Languedocian Occitan, Provençal, Nissart, and Vivarois. What do Béarn and the Nice region have in common? The only element uniting them in the long term is the language of their inhabitants, which is a local representation of Occitan.

The langue d’oïl is a Gallo-Romance language that developed in the northern part of France, southern Belgium, and the Channel Islands. It then encompassed different cousin dialects (French, Orléanais, Burgundian-Morvandiau, Champenois, Lorraine Roman, Picard, Walloon, Norman, Gallo, Angevin, Tourangeau, Sarthois, Mayennais, Percheron, Franc-Comtois, Poitevin, Saintongeais, Berrichon, Bourbonnais). This northern linguistic group retained an important Celtic substrate and underwent significant influence from Germanic dialects.

From one oïl dialect to another, people managed to understand each other, thanks to administrative writing. In Paris (11th-12th centuries), a French “porous” to all these dialects was spoken, which became a linguistic reference in the 14th century as the city became the political and administrative capital of the kingdom.

The Progression of the French Language in the Kingdom of France

French is the medieval “vulgar” (living) language that experienced its strongest expansion outside its territory of origin, the oïl domain. The first “export” of French was a consequence of the Norman conquest of England in 1066: a cousin variant of French, Anglo-Norman, was established in the British Isles. At the same time, the clergy of the kingdom perpetuated Latin habits. In the 1230s-1240s, the practice of French spread in legal and administrative acts established by the Dukes of Lorraine and the Counts of Luxembourg.

In the Kingdom of France, the Dukes of Champagne and Burgundy (great fiefs vassal to the king) began to use it. French penetrated the Duchy of Brittany during the years 1250 to 1280; it spread from the middle of the 13th century in Flanders. On the other hand, the center and west of the oïl domain remained very faithful to Latin throughout the 13th century.

As French became the language favored by the king, it gradually replaced other vernacular languages of the kingdom. In southern Roman France, the French language penetrated rather slowly: introduced around 1250 in the Dauphiné, it spilled over into the lands of the Germanic Empire from the end of the 13th century (French-speaking Switzerland, Savoy, and the Aosta Valley) and imposed itself in Lyon in the 15th century. In the oc domain, the penetration of legal French did not begin with the Albigensian Crusade.

It was late and gradual: present after 1350 in Auvergne and Limousin, French imposed itself in Languedoc and Provence after 1450. At the beginning of the 16th century, only the Pyrenees maintained a written production exclusively in the Occitan language; however, in the oc domain, the role of the king’s language was still limited because Latin and local vernacular languages coexisted with written French.

In the 14th century, French became the language of royal administration at the local level of bailiwicks and seneschalties, then at the central level of the Chancellery and Parliament, until it supplanted Latin after the ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts in 1539.

Forty percent of the words in our dictionaries were forged between the 14th and 16th centuries: this is the period of “Middle French.

” The emergence of a standardized linguistic form, modern French, did not occur before the 17th century, with the creation of the French Academy.

A Multilingual Metropolitan France

Today’s France is largely multilingual, thanks to its exceptional linguistic heritage, composed of five Romance languages (oïl domain, Occitan, Catalan, Franco-Provençal, and Corsican), three Germanic languages (Alsatian, Franconian, and Western Flemish), one Celtic language (Breton), and one pre-Indo-European language (Basque). Not to mention the French-based creole languages (America, West Indies, Indian Ocean, Pacific) and all the languages of immigration!