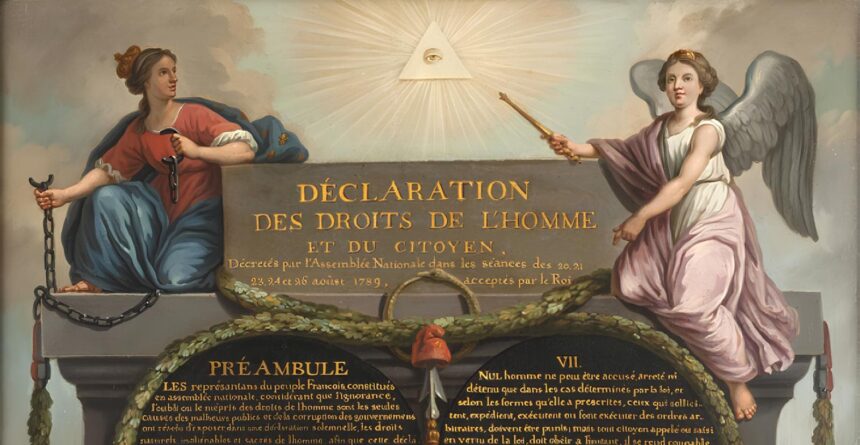

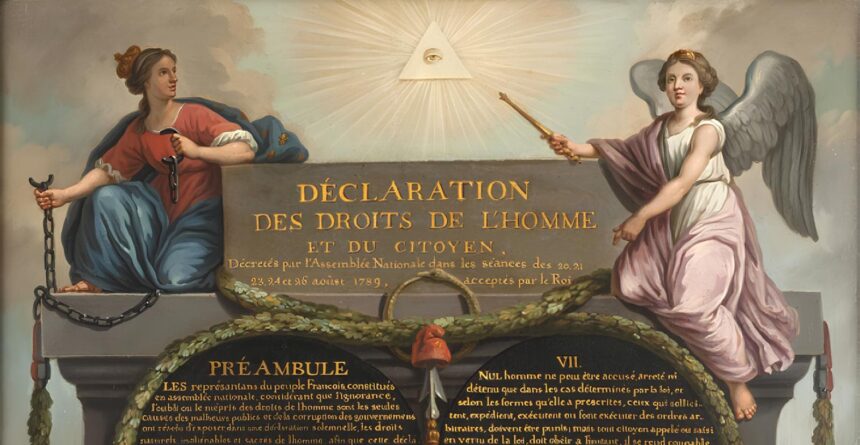

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

Drafted in 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is a text that sets out the natural and inalienable rights of individuals.

Drafted in 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is a text that sets out the natural and inalienable rights of individuals.