For over 70 years, various Greek cities came together to form the Delian League (478–449 BC), also known as the First Athenian League, to oppose the Persian Empire. The threats of the Persian Empire against the Greek city-states never ceased. Because of their frequency and scope, these Greco-Persian Wars (499–449 BC) eventually led to the Greeks becoming one nation. As a mark of their cooperation and equality, they put their wealth on Delos Island, one of the Cyclades Islands, home to a temple dedicated to Apollo, which is therefore worshipped throughout Greece.

But Athens wasted no time in assuming a leadership role within the Delian League by amassing the confederation’s wealth, collecting tribute, and imposing its colonies on the rest of the world. But there was anger at this behavior. After the Peace of Callias in 449 BC, the Delian League became meaningless, as Athens managed to maintain its supremacy only until Sparta conquered the city, which initiated the Thirty Tyrants period in Athens.

Who created the Delian League

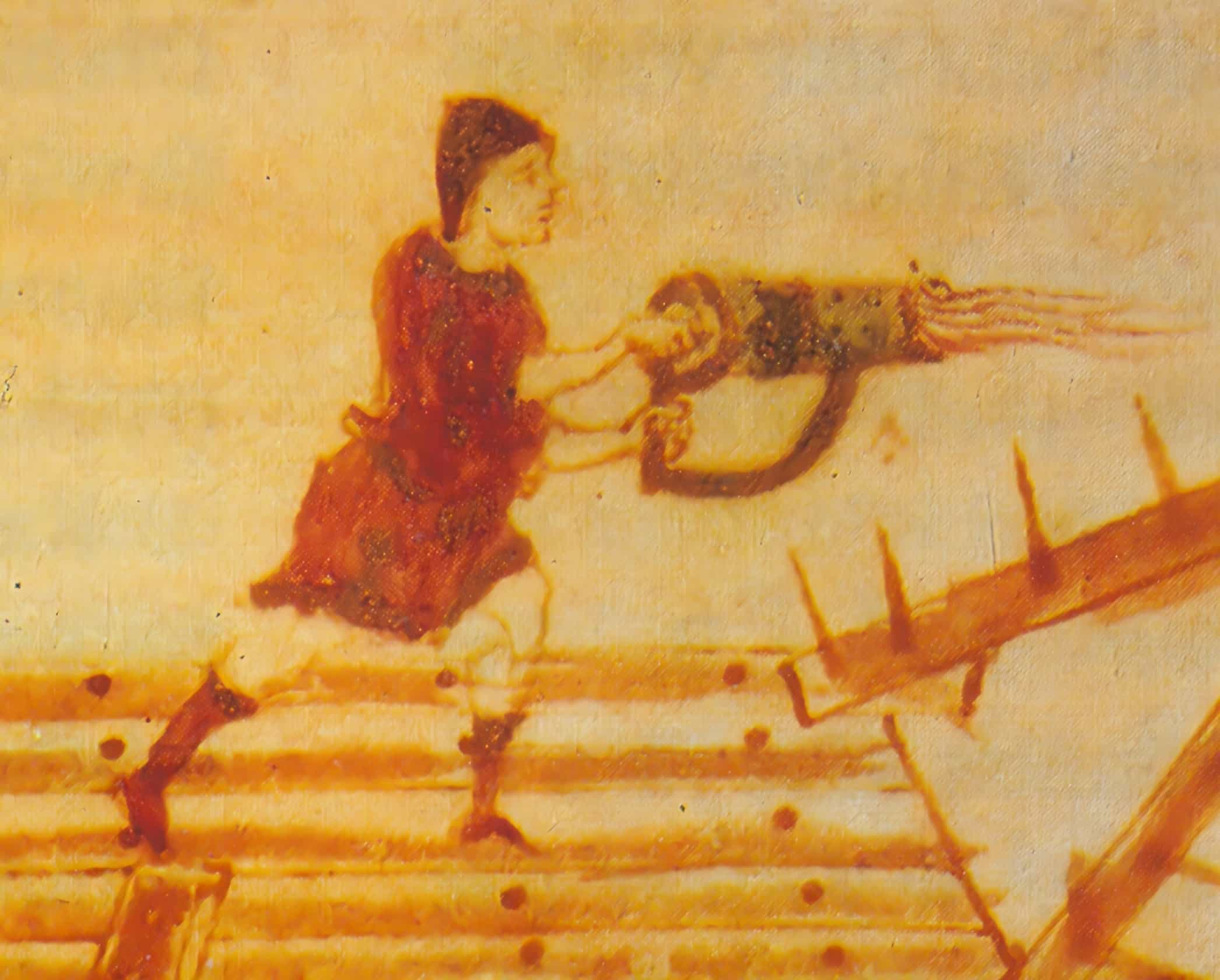

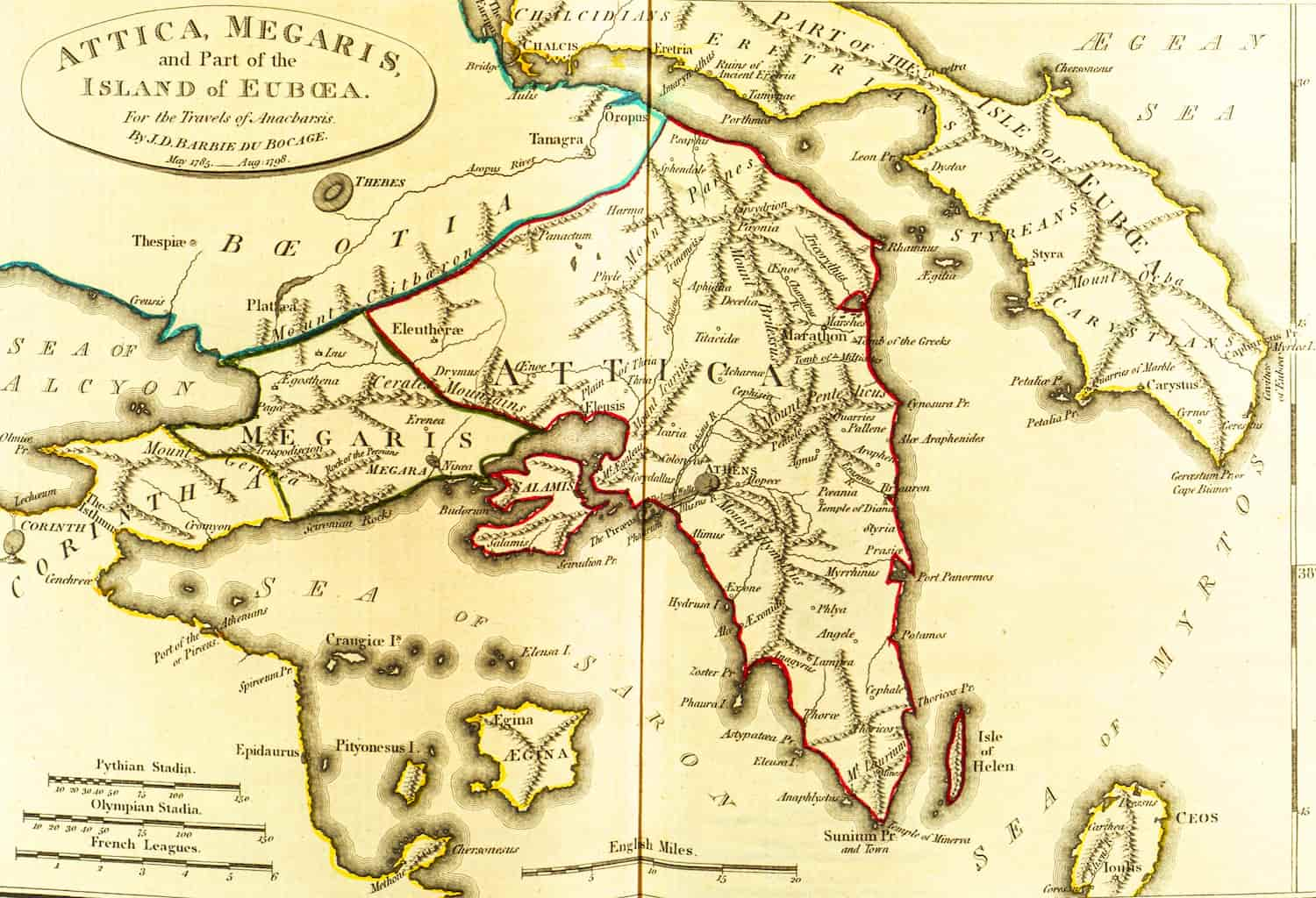

Both Themistocles and Aristides, two prominent Athenians, were instrumental in establishing the Delian League. Themistocles led the Athenian fleet to victory in the Battle of Salamis, giving Greece a crucial boost in its fight against the Persians, and was responsible for establishing the foundations of the modern Port of Piraeus. Aristides (Aristides the Just) was a key strategos (military general) at the 490 BC Battle of Marathon, when the Greeks triumphed against the Persians.

The plan was to pool resources like ships, people, and money in order to better prepare for any future conflicts that could be initiated by the Persians. As a precaution against war and the seizure of power by one city over another, the Delian League’s treasury was housed on the island of Delos, which had a temple dedicated to Apollo and where no permanent residents were allowed due to the island’s status as a Panhellenic sanctuary. That’s why the League was known as “Delos,” after the island that protected the Greek treasure.

Nearly 250 Greek cities joined together to form the Delian League. Most of these people lived in the regions of Ionia, Caria, Hellespont, Thrace, and Delos Island. What this meant was that the Aegean Sea and the shores of Asia Minor were the primary focus of League efforts. However, a vital city—Sparta, one of Athens’ biggest enemies—was not a part of this alliance, and this eventually led to the breakup of the Delian League.

The islands of Chios, Lesbos, Thasos, and Samos were home to cities with the military might to provide the Delian League with ships. The minority paid homage to the majority in the form of goods and money. There were occasional uprisings among the Delian League cities, such as the ones on Thasos and Samos or in a number of Ionian cities in 490 BC, despite the alliance of these cities against the Persians. Skyros, like Naxos, rebelled in 469 BC and was ruthlessly put down.

How Athens took control of the Delian League

Pericles led Athens into its political, economic, and cultural golden age. Pericles advocated for a stronger navy and did much throughout his life to build Athens’ power.

Although the Delian League was founded on a commitment to equality, Athens dominated the organization for a number of reasons. The first factor in Athens’ favor was that, due to the importance of the war fleet, it was the natural commander of the ships and the accompanying expenses. In fact, a few years earlier, a big chunk of the money that Athens made from the silver mine at Laurion was used to build warships.

Thasos and Samos, on the other hand, were only two of many Greek cities with formidable naval forces. But these cities, like the others, were destroyed in revolt because they found Athens’ tribute demands exorbitant, especially when Athens chose to quadruple the payment in 425 BC. In this respect, Athens was left completely free to dominate the maritime arena. In addition, in 452 BC, Pericles transported the riches of Delian to Athens under the guise of the Persian threat. Athens’ access to these crucial resources helped to ensure its dominance. After the Acropolis was damaged by the Persian invasion in 480 BC, Pericles wasted no time in putting it to good use.

How did Pericles justify the transformation of the Delian League?

Pericles had no shortage of arguments to legitimize the Athenian takeover of the Delian League. He told the rebel cities that Athens, as the key city in the defense, especially the naval defense, against the Persians, deserved special rewards like building the treasury in the middle of the city.

Indeed, Pericles underlined the efforts that made Athens the leading city of the Delian League: Athens had delivered aid to the Egyptians (in vain) when they were attacked by the Persians; Athens had also directed its own troops towards Corinth, where the uprising was raging. Pericles also emphasized that as long as Athens ensured the protection of the Delian League members, no one would have any reason to object. Pericles announced that if a Greek city successfully fended off a Persian attack, it would no longer have to pay tribute to the League.

How does the Delian League work

In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides described how the Delian League was established at first by agreements reached during conferences on Delos Island, a sacred site for the ancient Greeks. Every year, all the participating cities present a unified homage at that location. But Athens’ newfound dominance altered things slightly. All the crucial choices in the Delian League were now made in Athens. They were also responsible for collecting and estimating the value of the League’s treasure, which had been there since 454 BC.

One factor that affected the final figure was how cooperative individual cities were with one another. To eliminate the possibility of counterfeiting, a law mandated all the cities to adopt Athens’ weights and measures standards. Therefore, the Delian League’s operations became more centralized. Furthermore, the Delian League’s funding of the Acropolis restoration projects demonstrated its commitment to maintaining Athens’ cultural and religious dominance more than anything. During the Panathenaea Festival of Athens, the city, in fact, demanded sacrificial animals from its allies (440 BC). And the allies participated in the games as Athenian colonies five years later as well. In addition, magistrates from Athens were sent to each Delian member city to guarantee that their responsibilities were met.

How was the Delian League dissolved

During the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), Athens fell to Sparta, a city that had been antagonistic to Athens since before the Delian League was formed. In the Peloponnesian League (550–356 BC), dominated by Sparta, Sparta recruited allies, including the cities of Boiotia and Thebes. Sparta continued to challenge Athens, capitalizing on uprisings within the Delian League. Sparta finally conquered Athens in 404 BC, with the help of Persian funding.

Key dates of the Delian League

478 BC: Formation of the Delian League

The Delian League was founded to counter a resistance group stronger than the Persians, and it was led by two Athenians: Themistocles and Aristide. Even when the Greco-Persian Wars (499–449 BC) were finally over, the threat was still present. With the formation of the Delian League, more than 250 Greek cities agreed to join forces and create a treasure, which was first sent to a temple on Delos Island and later to the Parthenon Temple in Athens.

471 BC: Ostracism of Themistocles

Despite his victory at Salamis and subsequent prestige, Themistocles’ political fortunes began to fall in the year 470, coinciding with Cimon’s ascension to power. As a result of their disagreements over foreign policy, Cimon banished Themistocles from the city for 10 years as punishment for his desire to become a tyrant. Although Cimon was more concerned about the Persians, Themistocles believed Sparta to be the real enemy of Athens. Because of ostracism, the best Greek generals in Athens were often banished from their duties.

464 BC: Sparta victim of an earthquake and a revolt

An earthquake rocked Sparta, causing widespread destruction and chaos. The helots (serfs) launched a full-scale revolt against their masters. The rebellion, which undoubtedly took advantage of the city’s poor contextual position, persisted for a fixed period of time and caused a diplomatic rift with Athens. The Lacedaemonians’ (Spartan residents’) refusal to accept Athens’s help offer was the eventual result of their own intransigence.

461 BC: Revolt of the Helots in Sparta

After a devastating earthquake struck Sparta, the city’s helots—who had a position akin to medieval serfs—rebelled. Because they were humiliated and hated by the Spartans for too long. When Athens offered to aid Sparta, the latter city-state rejected the Athenians. Feeling humiliated, Athens decided to end the peace with Sparta.

454 BC: The treasure of the Delian League is transferred to the Parthenon

The transfer of the Delian League’s riches to the Parthenon Temple of Athens was a symbolic act that solidified Athens’ position as the dominant power in the Delian League and the Aegean Sea. The Delian League became an empire, a “hegemony” of Athens, after multiple battles to keep the cities in the League by force. Truth be told, Athens’ decision of which city to invite to the Delian League and how much credit to give them for their efforts was the primary financial factor in Athens’ desire for more control.

451 BC: Political Reforms in Athens

Pericles, who was elected in 443 BC, ushered in a number of reforms in Athens’ governance. People formerly considered third-class could now achieve the rank of archon (chief magistrate). And Areopagus’ (the Council of Athens) power was not restricted. To encourage residents to seek higher government positions, the various types of magistrates got allowances. Last but not least, Athenian citizenship was now passed exclusively on to the offspring of two citizen parents (as opposed to only one previously).

449 BC: Pericles had the Parthenon built

The Parthenon, the most well-known emblem of Athens, was a temple on the Athenian acropolis that was built by Pericles with the treasure of the Delian League, which was now brought to Athens. The treasure of the League was now located at the new Athenian temple. A pharaonic endeavor, it helped spread Athens’ religion and culture.

443 BC: Pericles as a military general

In 443 BC, Pericles was elected for the first time to the rank of strategos, or military general. He stayed in this role for 15 years. With his help, Athens controlled the Delian League and established itself as the dominant power in the region. He commanded Athenian armies in the Peloponnesian War and was known for advancing democratic reforms at the city-state level. During the Delian League, he was the most powerful ruler of the Athenian empire.

May 431 BC: Sparta invades Attica

Under Archidamus II’s command, Sparta and its Peloponnesian League allies attacked Attica (the countryside of Athens) on many occasions. Pericles would rather watch the destruction unfold than do anything. The Plague of Athens (430 BC) coincided with the commencement of the Peloponnesian War, which was sparked by a series of invasions and reprisals.

September 429 BC: Death of Pericles

A few months after being re-elected as Athens’ chief general, Pericles died of the Plague of Athens (a pandemic whose cause is unclear). He had ruled Athens practically constantly from 443 BC to 429 BC. His two sons and hundreds of other Athenians perished with him in the catastrophic epidemic that swept Athens at the time. He left Athens at the cusp of the pivotal Peloponnesian War, when he was 66 years old.

August 425 BC: Athenian victory at Sphacteria

At Sphacteria, the Athenian Army defeated the Spartan Army and captured around 400 hoplites. Since at least a hundred of these warriors were Spartans, it was clear that this was a psychological triumph as well; these troops were widely regarded as unbeatable. In the 10 years of fighting before the Peace of Nicias, however, the outcome was a draw for both sides.

March 421 BC: Peace of Nicias

After 10 years of fighting, Athens and Sparta finally made peace and agreed to maintain it for the next 50 years. With the Peace of Nicias, the Peloponnesian War was put on hold. This conflict arose from competition between the oligarchic rule of Sparta, which tried to maintain its supremacy, and the Athenian democracy, which desired to expand (even to impose) its model via the Delian League. As Athens bled to death and the Delian League crumbled, Sparta’s allies remained steadfast in their opposition to the peace.

May 414 BC: The desecration of Hermes

An incident involving the desecration of the statues of Hermes, or the hermai (heads of the god Hermes), brought the Athenian general Alcibiades to the forefront. Large-scale panic ensued as the city of Athens worried that a conspiracy was being hatched against it. Alcibiades was getting ready for the trip to Syracuse. He was ready to face the accusations, and he wanted to know what would happen before he left the city.

He was finally released. But this Socratic student and direct descendant of Pericles was later summoned back to Athens, where he faced the death sentence for his treachery. Therefore, Alcibiades sided with Sparta and persuaded the Lacedemonians to protect Syracuse while launching an assault on Athens.

August 414 BC: Breaking of the Peace of Nicias between Athens and Sparta

Sparta declared that the peace of Nicias was broken in response to ongoing fighting between Greek cities and Athens’ expedition in Sicily against Syracuse. This peace, which was supposed to last 50 years, lasted just seven. Many Greek cities were involved in the bloody Peloponnesian War.

November 16, 414 BC: Battle of Assinaros River

However, Nicias, who commanded one of the two Athenian armies in Sicily, was unable to cross the Assinaros River and fell into Syracuse’s trap. His army was wiped out, and he was put to death. Demosthenes, who was leading the opposing force, was also put to death, and his men were now being held prisoner in barracks at Latomies. Slavery was a common fate for those who survived the harsh circumstances of captivity. Athens lost thousands of warriors and hundreds of treasuries in the voyage to Syracuse, and Sparta reoccupied Attica with an army.

June 411 BC: Establishment of the Regime of Four Hundred

Athens was in the midst of a political and financial crisis after the failed Sicily mission. The democratic system was subsequently supplanted by an oligarchic one, which was called the Council of the Four Hundred. But the Army in Samos was not prepared to accept it. And peace talks between the Four Hundred Regime and Sparta ended in failure as well. As of June, the “Five Thousand” regime took the place of “Four Hundred.” However, the people and the military ensured its defeat, bringing democracy back. These developments paved the way for Alcibiades’ eventual homecoming.

March 410 BC: Victory of Athens in Cyzicus

Alcibiades utilized the chaos of Athens’ domestic affairs as an opportunity to win back the support of his fellow citizens through a string of military successes. He achieved victory at the Battle of Cyzicus while commanding the fleet. Athens was strengthened by their third straight win against Sparta. Therefore, the Spartans offered peace proposals throughout the summer, but it was Athens’ turn to reject them.

August 406 BC: Death sentence for the Generals of Arginusae

After the Battle of Arginusae, the victorious generals and generals’ advisors were tried in Athens and sentenced to death. The Athenians still held the Spartans responsible for abandoning the 25 disabled or sunken Athenian triremes in the middle of the ocean after a storm. This was the last triumph for Athens in the Peloponnesian War. Alcibiades was sentenced to a year of exile after the defeat.

September 405 BC: Lysander destroys the Athenian fleet

Lysander, with 180 Spartan ships in a surprise assault, severely defeated the Athenian fleet stationed at Aegospotami in the Battle of Aegospotami. The fleet, commanded by Conon and consisting of 170 triremes, set out to assure the supply of food and other necessities to the city of Athens. It was clear that the city’s current predicament was unsustainable. Sparta was susceptible to falling under any siege because it was about to be deprived of both its military might and its ability to provide for its citizens.

April 22, 404 BC: Fall of Athens

After being surrounded for so long and realizing that they were out of food and naval weapons, Athens gave up and agreed to Sparta’s terms. The great walls that encircled Athens were a sign of its dominance, and so they were destroyed along with the Empire that had existed through the Delian League. More specifically, an oligarchic paradigm known as the “Thirty Tyrants” had superseded the democracy in the country.

After that, Sparta imposed oligarchies ruled by 10 individuals on all the democracies based on the Athenian model of decarches. Those authoritarian and violent administrations were seen as a step backward, especially in Athens, where they were seen as a return to tyranny. Especially given that Athens was founded in opposition to tyranny and one-man rule. This brief, painful period was called the Thirty Tyrants.

Bibliography:

- Rhodes, Peter John (2006). A History of the Classical Greek World: 478–323 BC. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22565-2.

- Roisman, Joseph; Yardley, John C. (2011). Ancient Greece From Homer to Alexander: The Evidence. Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-12776-9.

- Larsen, J. A. O. (1940). “The Constitution and Original Purpose of the Delian League”. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 51: 175–213. doi:10.2307/310927. JSTOR 310927.