As the art of writing developed in Mesopotamia, so did the first formal educational institutions. Ancient cultures as diverse as Egypt, the Aztecs, Greece, and Rome were all concerned with passing on their knowledge to future generations. The term “school” stems from the ancient Greek scholē meaning “the suspension of labor” or “leisure.” Therefore, to claim that Charlemagne established the first school is not accurate. Although the Carolingian ruler indeed injected fresh energy into the educational system.

Who invented the school? The true role of Charlemagne

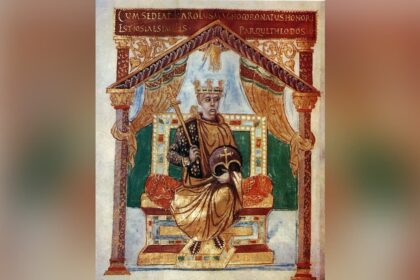

Several tribes of barbarians have moved into the area since the Western Roman Empire collapsed. Charlemagne, son of Pepin the Short and king of the Franks, tried to unite the Frankish realm, which at the time was divided by different languages and a mix of Christian and Pagan beliefs.

The future emperor had a lofty goal at the close of the 8th century: he wanted to expand access to education for as many people as possible. Charlemagne made the following proclamation in the year 789:

Sons of means and sons of birth should get together. That institutions dedicated to the education of males be set up. That there be well-corrected books and that the psalms, notes, chant, computation, and grammar be taught in each monastery.

This led him to create two sets of educational facilities in every monastery across his kingdom: one for training priests and another for the common populace. The boys were educated in the basics of the faith as well as reading, writing, grammar, mathematics, and astronomy by the priests.

Charlemagne established the Palatine School in the center of his palace in Aachen, and he made it a point to personally check in on the young kids every so often to make sure they were doing their homework. Not only did the school accept children from wealthy households, but it also accepted some of the top pupils from middle-class families.

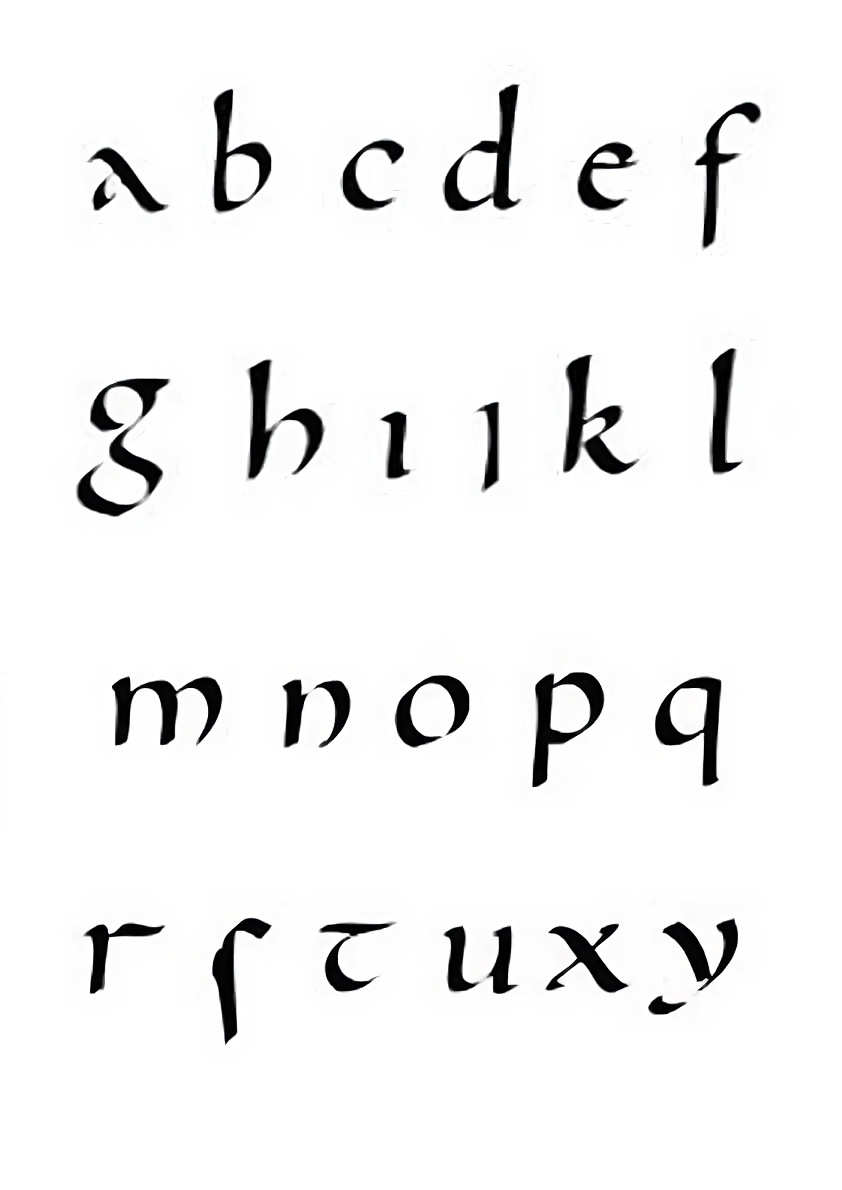

Charlemagne also began to simplify the writing by introducing lowercase Caroline (Carolingian minuscule) to make books simpler to grasp for the maximum number of people. Using punctuation, spacing between words, and rounded letters, this new writing style is quite similar to the way we write today.

Sources:

- Contreni, John J. (1995). “The Carolingian Renaissance: Education and Literary Culture”. In McKitterick, Rosamond (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 2, c.700–c.900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13905571-0.

- Kreis, Steven (2009). “Charlemagne and the Carolingian Renaissance”. The History Guide. Retrieved 15 October 2013.