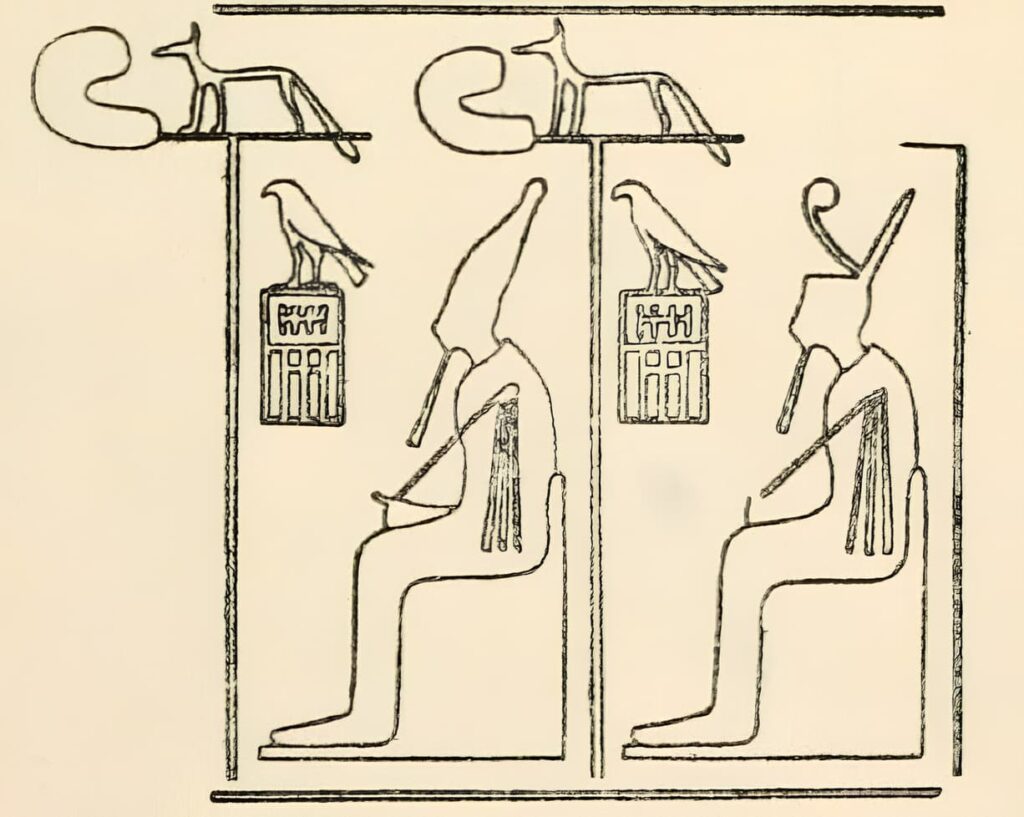

Djer, Hor Djer (Hr Dr, literal meaning “Hor the Grasper” or “Protector” or “Strong”, early 3rd millennium BCE) was the third pharaoh of the First Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. According to recent research, he may have ruled for about 47 years, from 2999 to 2952 BCE. Djer’s long reign was marked by innovations. The double depiction of Djer on a clay seal, seated on a throne, wearing either the Upper or Lower Egyptian crowns, indicates his authority over the whole of Egypt.

Name

In modern Egyptology, the name “Djer” is used to refer to this pharaoh, which is actually just one of his names, known as a Horus name. According to the Soviet historian Yu. Ya. Perepelkin, the Egyptian word “djer” (Egyptian transliteration: Dr) can best be translated into “grasp,” although the researcher acknowledges that “grasp” still may not accurately convey the Egyptian meaning.

Printing of a cylindrical seal containing the Sereque from Djer and Pharaoh wearing the crowns of the High and Lower Egypt.

Initially, in his post-war work on the Early Kingdom, Yu. Ya. Perepelkin provisionally translated Djer’s name as “Binder,” commenting as follows: “The meaning and exact pronunciation of the name of Horus, who inherited the Fighter Horus, are genuinely unknown. The transmission of ‘Hor Binder’ by me is purely conditional for convenience. The only, moreover, rather shaky support for it can be: the rare writing, by which the sheaf, denoting the actual name, is placed in the paws of the falcon Horus—just like with the predecessor, Horus the Fighter, a shield with a mace is handed to the falcon.” Later, while working on his “History of Ancient Egypt,” published in 2000, Yu. Ya. Perepelkin began to render Djer’s name as “Horus Restrainer,” but then leaned towards the latter rendition, “Horus Grasper.”

According to the German Egyptologist Wolfgang Helck, the name of the third king of the First Dynasty is represented as “Protector.” However, the hieroglyph “Bundles of Reeds” is unlikely to correspond to the correct description. It is more likely a kind of “Apron, chest protector, loincloth.” Perhaps this sign is based on the “Buto glyphs,” with which kings wrote their names.

Chronology

In modern Egyptology, many questions of the chronology of Ancient Egypt are subject to debate; for example, most dates of pharaohs’ reigns are relative, with the rule of thumb being that the older the reign, the less precise the date. This is particularly relevant for the representatives of the Early Kingdom – the dynasties of this period were considered mythical for some time. Over time, evidence of the existence of early pharaohs was found, and in our days, the level of inaccuracies and errors in determining the time of their reigns has been decreasing.

Some datings of Djer’s reign according to various researchers (dates given in BCE):

- 3100–3055 (45 years) – according to N. Grimal;

- 2980/2960 (?) – according to R. Krauss;

- 2999/2949–2952/2902 (47 years) – according to J. von Beckerath, “Chronology of the Pharaohs of Egypt”;

- 2939–2892 (47 years) – according to J. Malek;

- 2870–2823+25 (47 years) – generalized chronology edited by E. Hornung, R. Krauss, and D. Warburton, “Chronology of Ancient Egypt” (the most recent work on Egyptian chronology).

Monuments of Djer’s reign

The Abydos list names the second pharaoh after Meni as Teti (I); according to the Turin Royal List, this pharaoh was called Iteti; according to Manetho, it was Atotis.

The priest Manetho, who wrote the history of Egypt in the 3rd century BCE, preserved only in excerpts from later ancient authors, attributes 57 years to Atotis’ rule. However, the study of the chronicle of the Old Kingdom, the so-called Palermo Stone, also broken into pieces, most of which are lost, suggests that Djer’s reign lasted 41 years and several months. The name of King Djer is not preserved in this chronicle, and these years are attributed to him based on general conclusions.

The years from the 1st to the 10th are described in the second row of the main part of this chronicle, kept in the museum of the city of Palermo (hence the name), while another 9 years concerning the middle of his reign are preserved on a fragment kept in the Cairo Museum (Cairo fragment). The chronicle tells about celebrations in honor of various gods of Egypt, dedicatory offerings to ancient Egyptian gods, the height of the Nile during floods, and similar facts, not significantly enriching knowledge of the history of that period.

On the Cairo fragment of the Palermo Stone, alongside the “Horus name” Djer, there is another name, possibly an early form of the later “golden name”: Ni-nebu (meaning “golden”). However, this name of Djer is accepted very conditionally, as it is necessary to take into account that the “golden name” officially entered the titulature of the Egyptian pharaoh only during Djoser’s reign (III Dynasty).

The same Cairo fragment also mentions a possible “personal name” of the ruler, which is read as Iteti and enclosed in a cartouche. Here we also encounter an anachronism, as the writing of the pharaoh’s name enclosed in a cartouche was introduced only starting with the pharaoh Nebka (end of the III Dynasty).

- Year 1 – Service to Horus; Birth of Anubis

- Year 2 – Circumambulation of the Two Lands; Festival of Desher

- Year 3 – Service to Horus; Birth of Thoth

- Year 4 – Planning (of the building) “Friend of the Gods”; Festival of Sokar

- Year 5 – Service to Horus; Subduing (of the land) Setet

- Year 6 – Rising of the king of Upper Egypt; Birth of Ha

- Year 7 – Service to Horus; Birth of Neith

- Year 8 – (building) “Friend of the Gods”; Festival of Desher

- Year 9 – Service to Horus; Birth of Anubis

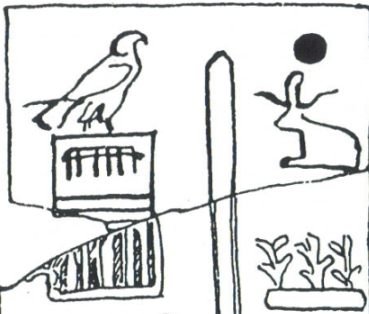

Among the documents related to the reign of King Djer, the most important are two labels: one made of ivory and originating from Abydos, and the other made of wood and originating from Saqqara. Such labels were evidently attached to certain objects and dated to a specific year of the king’s reign, notable for particular events considered significant for that period.

Unfortunately, contemporary knowledge of archaic hieroglyphs is so limited that a reliable translation of these invaluable texts is currently beyond reach. It is only possible to decipher individual words and word groups, which yields highly questionable interpretations. Of the two labels mentioned, the one from Abydos seems to record the king’s visit to Buto and Sais, the sacred cities of Lower Egypt. The Saqqara label evidently recalls some important event, most likely a religious festival during which human sacrifices were made.

The mother of Djer is possibly to be identified as a lady named Kenet-Hapi. However, her name is only attested on the famous Cairo Stone and not confirmed by other sources. The wife of Hor-Djer was possibly a lady named Kher-Neith, a name systematically found on monuments to Hor-Djer.

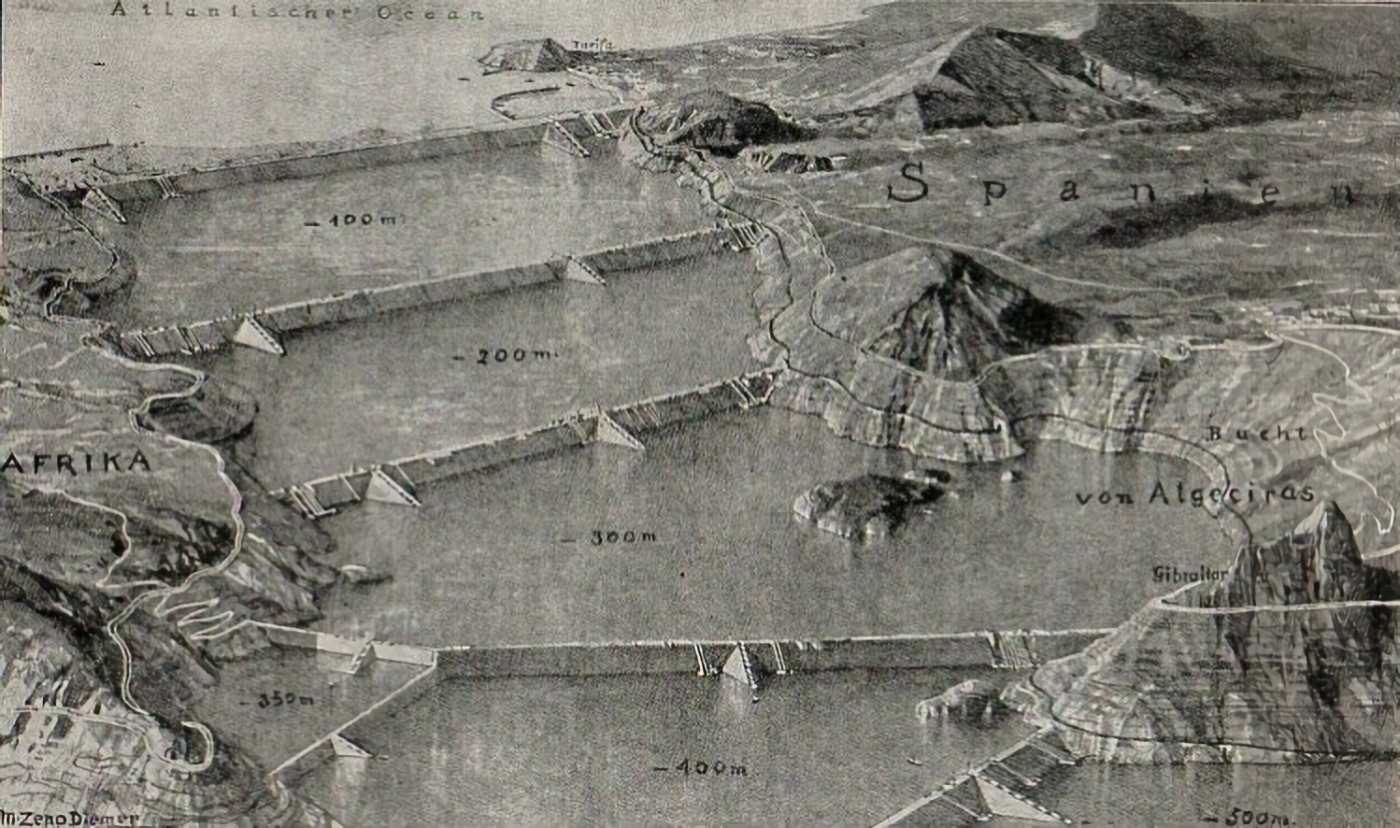

Military Campaigns

It is probable that Djer was a successful conqueror. He continued the wars in Nubia started by his predecessors, and his troops penetrated further south, reaching the second cataract of the Nile. Near Wadi Halfa in Gebel Sheikh Suliman, on the western bank of the Nile, a rock inscription (now in the National Museum of Khartoum) displays the “Horus name” (serkh) of King Djer, with a human figure in the pose of a captive before the name. Although the hands of this figure should theoretically have been tied behind them, they continue to hold a bow, a symbol of Nubia. Another captive is depicted tied by the neck to an Egyptian boat, which likely brought the pharaoh’s army. Below the boat lie the bodies of slain enemy warriors. Whether this primitive monument represents merely a punitive expedition of King Djer or a generalized process of conquest of these territories cannot be determined. In any case, objects made by Egyptian craftsmen and belonging to this period were indeed found in Lower Nubia.

It is highly likely that King Djer conducted military operations on his western border, as an alabaster palette with a roughly drawn inscription from his tomb in Saqqara shows the king in the typical pose of a victorious pharaoh, slaying a Libyan captive. The eastern border did not go unnoticed either. One of the years of Djer’s reign is marked in the Cairo fragment of the Palermo Stone as “the year of the defeat of the northeast (Setechiu).” In later sources, this term referred to all of Asia adjacent to Egypt, and it is now difficult to determine precisely where the expedition was sent during Djer’s reign.

However, sources from the En Besor area, a locality in southern Israel, indicate that there were indeed some trade and cultural connections between Ancient Egypt of the First Dynasty and southern Palestine. Moreover, fragments of pottery of Syro-Palestinian origin were found in the tomb of Djer, which further proves the possibility of such distant trade connections at that time.

Perhaps it was precisely there that the expedition of Pharaoh Hor-Djer was directed. Some Egyptologists, however, doubt that Egypt could organize such distant expeditions in the early stages and tend to believe that at that time, by the land of Setechiu, the Sinai Peninsula was meant. Precious turquoise objects, traditionally mined in Sinai, were found both in the tomb of Djer and in the tomb of his daughter Merneith. Copper tools and vessels, discovered in large quantities in the tomb of one of Djer’s contemporaries, also testify to this king’s campaign on the copper-rich Sinai Peninsula.

The Flourishing of Egypt

The strengthening of Egypt as a unified state continued throughout Djer’s reign, and there are no records of internal discord. On the contrary, there appears to have been a significant step towards strengthening Egypt economically and increasing its prosperity.

During the reign of Pharaoh Djer, the art of Ancient Egypt further developed. Some Egyptologists even speak of the greatest breakthrough in the development of art during Djer’s reign. This is indicated by the increased production of art objects and crafts, outstanding examples of which can be found among the jewelry from the southern royal tomb at Abydos, in the large collection of copper vessels, tools, and weapons from the northern tomb of the same king in Saqqara; among the unquestionable masterpieces is a magnificent knife, albeit made of flint, with a golden handle. The copper tools and vessels found in the king’s tomb are a vivid example of the development of blacksmithing during his reign.

Moreover, the reign of Pharaoh Djer dates the first known three-dimensional royal statue to this day: a headless statue from the temple of the goddess Satis in Elephantine. It depicts a figure seated on a throne, most likely representing Hor-Djer.

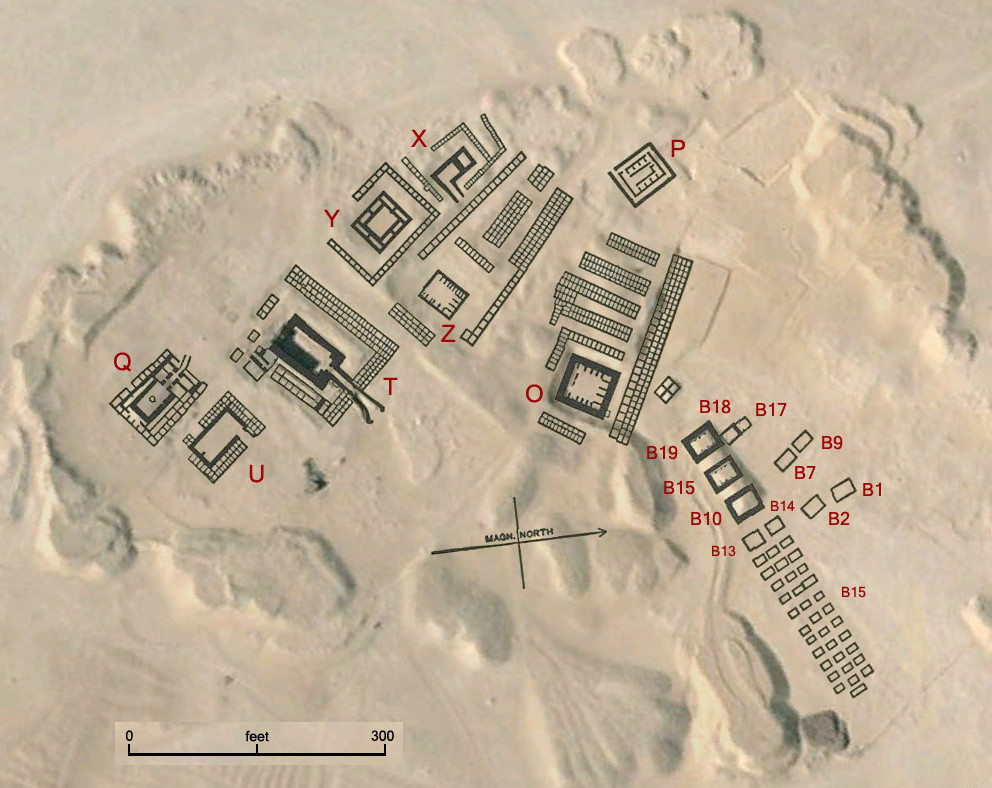

Tomb in Abydos

Like his predecessor Hor-Aha, Djer ordered the construction of two tombs for himself—one in the south and another in the north—which were intended to symbolize the full extent of the pharaoh’s power over both Upper and Lower Egypt.

The southern burial site of King Djer in Abydos (the Umm el-Qa’ab necropolis) is much larger than the nearby tomb of Hor-Aha. It consists of a large rectangular pit lined with bricks, with irregularly shaped storerooms on three sides. The burial chamber itself, or crypt, was apparently built of wood, and the entire tomb was originally covered with wooden beams and planks. Elements of the luxurious brazier are still preserved to this day. Nothing remains of the above-ground structure. The dimensions of the monument, including the restored above-ground structure, are 21.5 × 20 m. Next to Djer’s burial, 338 additional burials were found (containing the remains of servants sacrificed upon the completion of the king’s burial; most of the sacrifices were women, leading Egyptologists to believe that his harem was buried with the king), and nearby, there are another 269 tombs of his courtiers and dignitaries. Some of these burials feature small fragmentary inscriptions on rough stone stelae, but they are difficult to decipher. Mostly, they contain the names of the pharaoh’s entourage.

Fragments of a large royal stele were also discovered in the tomb, but the most remarkable find was the jewelry: four precious bracelets made of gold, turquoise, amethyst, and lapis lazuli on the bones of a human hand, which, for completely unknown reasons, were left behind by looters. These adornments are now housed in the Cairo Museum, while the remains of the mummy have remained unstudied and lost.

Djer’s tomb is also noteworthy for being revered in later times as the tomb of Osiris. Pilgrimages were made here from all over the country, lasting until Greek times.

Tomb in Saqqara

The northern tomb, conventionally attributed to Djer in Saqqara, is much larger than the Abydos monument of the same king and nearly the same size as Hor-Aha’s northern tomb. Nevertheless, it is much more carefully executed and exhibits features of further architectural development; this is especially true of the burial chamber and storage rooms, the number of which reaches seven, carved at a considerable depth from the ground surface. No secondary burials or stone enclosures (perimeter walls) were found around the tomb, but it is possible that they were destroyed during the construction of later tombs. The overall dimensions of the tomb are 41.30 × 15.15 m. Three boxes filled with copper items were found inside: 121 knives, 7 saws, 32 awls, 262 needles, 16 punches, 79 chisels, 102 adzes, 15 hoes, and other items.

Recent excavations in Saqqara led to the discovery of a large tomb belonging to Queen Kher-Neith, who, judging by the written evidence found in the tomb, can be reasonably considered Djer’s wife. Another tomb, similar in design and proportions, was discovered in Saqqara, and judging by the seals on the vessels found inside, it can be assumed that it also dates back to the reign of King Djer.

Atotis according to Manetho

Apparently, Djer, in his work, calls Manetho Atotis and says that he is the son and successor of Menes. Atotis, according to legend, built the citadel of Memphis and wrote a treatise on anatomy, as he was a physician. Monuments, of course, say nothing about a physician named Djer, but there are indirect but significant indications that medicine as a science was known in ancient times and that manuscripts even from the time of the earliest dynasties dealt with the treatment of known diseases and indicated known remedies.

For example, there is a manuscript that states that during the reign of Teti, a means was found to grow hair on the head. But even more important is the evidence of the Great Berlin Papyrus in the museum, which shows that medical art as a science dates back to the First Dynasty of Thinis. The manuscript contains a number of remedies for the “evil wound” (possibly leprosy) and other diseases.

Although the manuscript has rather childishly naive concepts of the internal structure of the human body, it nevertheless speaks of the importance of numerous and diverse “tubes,” as it calls them, apparently referring not only to respiratory and digestive pathways but also arteries and veins. The manuscript was written during the reign of Ramses II, but in one part it contains a whole excerpt borrowed, as the manuscript’s editor says, from a treatise written during the reign of the fifth king of the First Dynasty, Sepati.

References

- Amazon.com: A History of Ancient Egypt: 9781405160711: Van De Mieroop, Marc: Books

- Perepelkin Y. Y. Uk. cit., p. 60.

- Von Beckerath J. Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägypten. — S. 187—192.

- Hornung E., Krauss R. and Warburton D. Ancient Egyptian Chronology. — 2006. — S. 490.

- Section I. History of Ancient Egypt // History of the Ancient East / Edited by V. I. Kuzishchin. — 2nd ed. Moscow, Vysshaya shkola Publ., 1988. — S. 33—34.