The dryads, in Greek mythology, are nymphs (minor deities) associated with trees in general and specifically with oak trees. The term “dryads” was later used to refer to divine figures presiding over the worship of trees and forests. They are generally considered very shy creatures who rarely reveal themselves. The word dryad is used in a general sense for the nymphs that lived in the forest, although the alseides are also nymphs associated with the woods and forests.

Etymology

The word “dryad” comes from ancient Greek Δρυάς / Dryás (genitive Δρυάδος / Dryádos), derived from δρῦς / drŷs, meaning “oak.” According to Émile Benveniste, the Indo-European root drew and the Greek drŷs, equivalents of the German treu, originally meant “that which is solid or firm” and were later used to refer to the tree, especially the oak. This root not only gave rise to the term “dryads” but also to a series of words expressing trust and fidelity, such as trauen and trust.

Mythological Mentions

The dryads emerged from a tree called the “Tree of the Hesperides.” Some of them would go to the Garden of the Hesperides to protect the golden apples it contained. Dryads were not immortal but could live for a very long time. Among the most well-known is Eurydice, the wife of Orpheus. Late tradition made a distinction between dryads and hamadryads, with the latter specifically tied to a tree, while the former roamed freely in the forests.

Their life cycle is immensely higher than that of a mortal man. In the story of Heracles Eromenos Hylas, the dryads possess eternal life and imperishable beauty. The Sibyl Herophile lived to be 900 years old. Although the nymph Echemea is pierced by the arrows of Artemis, she does not die.

The first humans originated from “Ash-women,” who, along with the Erinyes and Giants, emerged from the seed of Uranus. The nymphs of the ash trees were called Meliae. Even according to Homer, tree spirits are the mothers of humanity. The river god Phoroneus had the nymph Melie as his mother. A parallel for a tree as the progenitor of humanity is found in Germanic mythology, as seen in Yggdrasil. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the rape of the nymph Callisto, a companion of the goddess Diana, by Jupiter, is described.

Metamorphoses

The poet Ovid recounts in his Metamorphoses that a man named Erysichthon became completely mad and sacrilegious. He attacked with an axe an oak of Ceres while the dryads danced around: “There stood a vast oak, its trunk age-old, surrounded by ribbons, commemorative tablets, and garlands, evidence of fulfilled vows. In its shade, the dryads led their joyful dances, often with intertwined hands, forming a circle around the trunk, and it took them fifteen fathoms to gauge its enormous mass.”

When Erysichthon struck the tree with his weapon, “barely had the sacrilegious hand made a wound in the trunk when the split bark let out blood; thus when a massive bull chosen for sacrifice has fallen before the altars, blood spurts from its torn neck.” A witness to the scene tries to stop him, but Erysichthon cuts off his head with his axe. The goddess Ceres punishes him by sending Hunger to visit him in his sleep, so that after devouring all his possessions, Erysichthon begins to devour himself.

Marriages

Dryads could marry, as one of them, Eurydice, is described as the wife of Orpheus, and Pausanias says that the wife of Arcas, son of Zeus and Callisto, was a dryad.

Meliae

The Meliae were nymphs who inhabited woods or groves of ash trees, particularly protecting children who were sometimes abandoned or suspended from tree branches due to their unwanted birth. However, other mythologists consider the Meliae (or epimelides) to be nymphs devoted to the care of herds. Their mother was the daughter of the Ocean, Melie, who was loved by Apollo, and she also bore two sons, Tereus and the seer Ismenos.

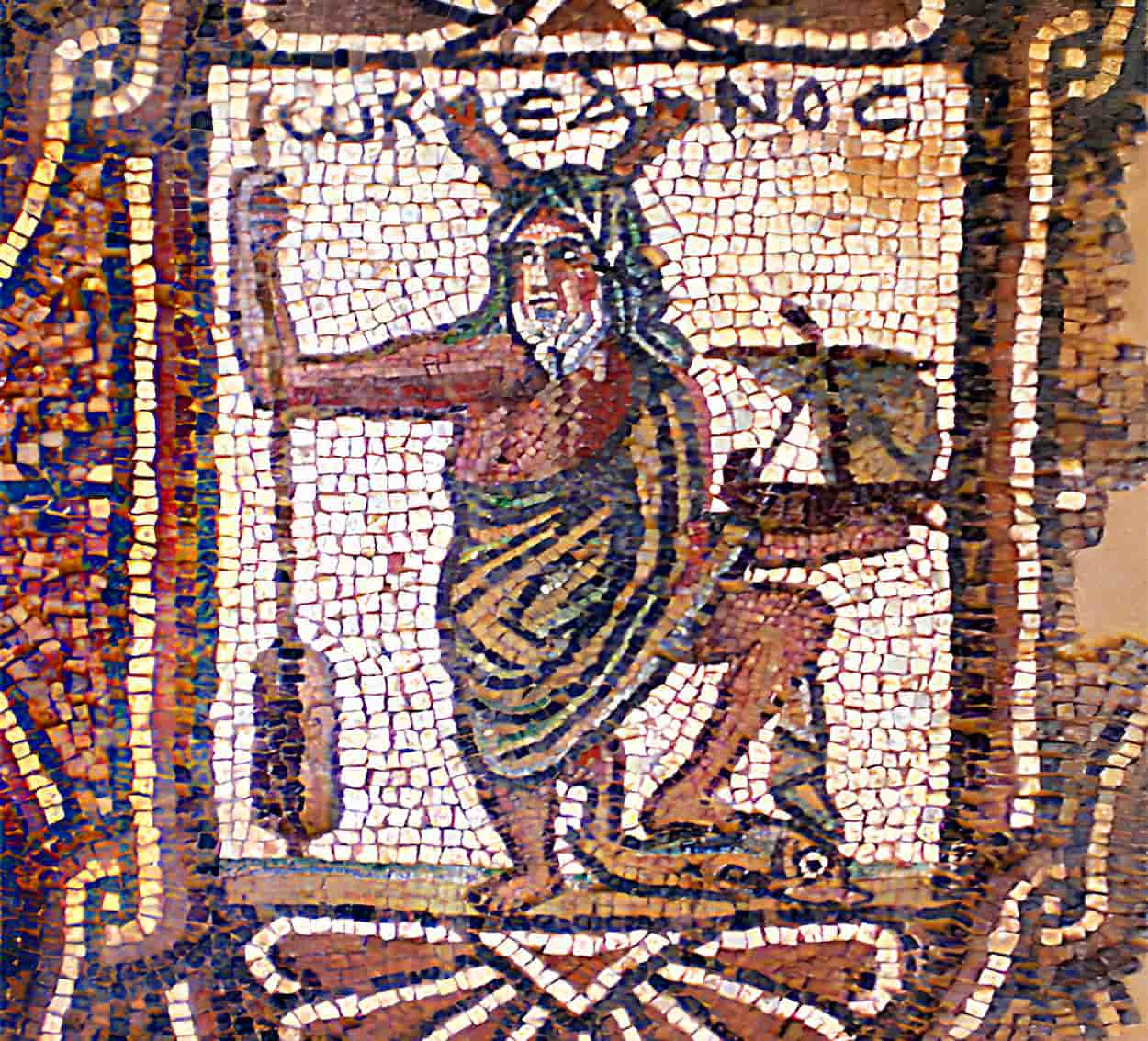

Hamadryads

Unlike dryads, hamadryads were specifically attached to a tree and would die with it if it was cut down. The Hamadryads are the souls of trees. Due to the connection between the tree and the soul, Hamadryads are bound to the life or death of their tree. If Hamadryad’s tree dies, so does her life. The bond between the Dryad and the tree arose from the belief that with the emergence of a tree, the corresponding Dryad within it also comes into existence simultaneously. If a Dryad is separated from her tree for too long or if the tree suffers, the Dryad also suffers. Any harm inflicted upon the tree likewise affects the Dryad.

In the narrative of Erysichthon, the blood of the Dryad flows out of the tree, and the voice of the Dryad reveals the punishment for harming the tree. Cybele kills a tree nymph by striking blows at the tree. Hamadryads can temporarily leave their tree and move freely outside it. Over time, due to the intermingling of various nymph types, Hamadryads evolved into tree goddesses. For instance, Daphne became a Dryad associated with the laurel.

According to Pherenikos, the Hamadryads were the daughters of the woodland spirit Oxylos and his sister, the Dryad Hamadryas. The specifically named Hamadryads were Aigeiros, Ampelos, Balanos, Karya, Kraneia, Orea, Ptelea, and Syke. Additionally, Oxylos and Hamadryas had more daughters. The names of each of these daughters served as inspiration for the Greek name of a tree species. For example, Aigeiros represented the black poplar, Ampelos for the grapevine, Balanos for the oak, Karya for the nut tree (hazelnut and walnut tree, possibly also for the chestnut), Kraneia for the cornelian cherry, Orea for the black mulberry or the wild olive tree, Ptelea for the wych elm, and Syke for the fig tree.

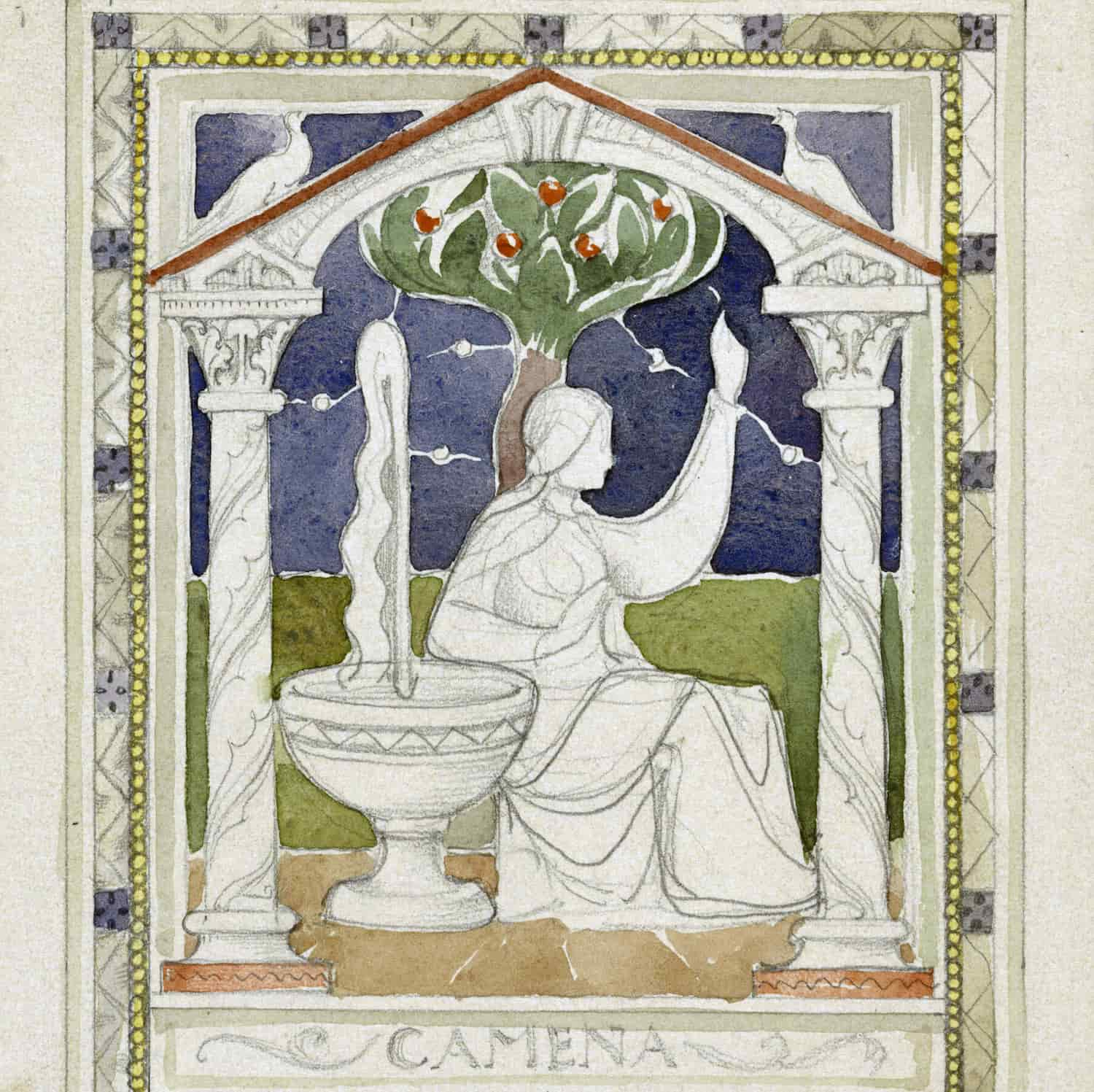

Dryad in Roman Mythology

In Roman mythology, there were nymphs of the oak groves, called querquetulanae or querquetulanae virae (women of the oak grove), who thus resembled the Greek dryads, although their origins are remote, suggesting that it was originally a Roman myth rather than a Greek embodiment. Such nymphs were responsible for producing the growth of the foliage of these trees. Its name derives from the Latin term for oak wood, querquetum, which in turn derives from the word quercum, oak. According to Festus, it was believed that in Rome there had already been an oak grove inside the city, at the entrance to the Querquetulana Gate, situated in the Servian Wall. It was the sacred grove of the Querquetulanas, whose annual reverdescence was affected by them.

Function

The belief of the Greco-Roman peoples in the real existence of woodland deities would have functioned to prevent them from destroying the forests. To cut down trees, they first had to consult the ministers of religion and obtain assurance from them that the dryads had abandoned the forest they intended to cut down.

Description

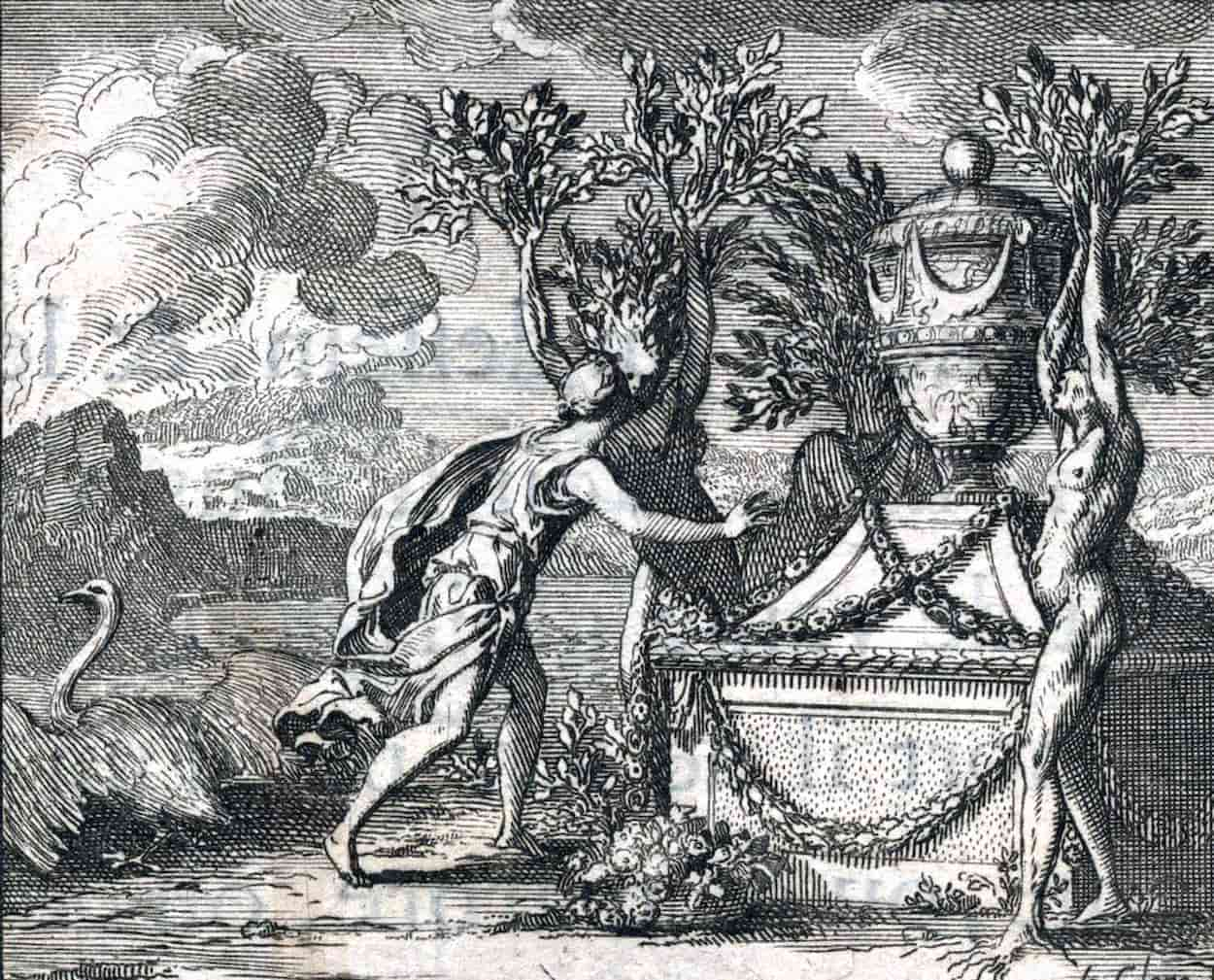

Dryads have the appearance of very beautiful young girls and embody the vegetative force of the forests in which they can freely roam day and night. Portrayed as minor protective deities of forests and woods, they were as strong and robust as they were fresh and light, forming dance choirs around the oaks dedicated to them. They could survive the trees under their protection because, unlike hamadryads, they were not bound to a specific tree.

These nymphs were represented in art as women whose lower bodies ended in a kind of arabesque, with elongated outlines resembling a trunk and the roots of a tree. The upper body was naked, shaded by abundant flowing hair over the nymph’s shoulders, swayed by the winds. The head often bore an oak leaf crown, and they sometimes held tree branches bearing their leaves and fruits. As guardians of the forests, nymphs were sometimes depicted with an axe in their hands to punish those who attacked the trees under their care. Other representations of dryads exist, clad in dark green fabric with tree bark shoes.

According to Édouard Brasey, dryads belong to the family of white ladies and are generally depicted as gentle and benevolent. They help lost travelers find their way, feed shepherds, play with children lost in the woods, and take care of horses in the stable. However, some of them are reputed to push travelers to the edge of cliffs.

Dryad Catalogue

- The Aegeides nymphs – some of them are Dryads, but all of them are Circe’s assistants on the island of Aeea.

- Eratus – a dryad of Arcadia, prophetess of Pan and wife of the eponymous king Arcade.

- Hamadriad or Hamadryad – mother of the nymphs Hamadryads by the rural demon Oxylus.

- The “Lyceae” nymphs – the nymphs of Mount Lyceum in Arcadia, who helped Rhea with the upbringing of the infant Zeus.

- Penelopeia – a dryad from Mount Cylene of Arcadia, mother of the satyr god Pan, in her union with Hermes.

- Titorea – a nymph of the nickname Parnassus, eponymous of the eponymous people.

- Melias, nymphs of ash trees.

Mentions in Literature

Dryads appear in John Milton’s famous poem “Paradise Lost,” Coleridge’s works, and Thackeray’s “The Virginians.” In 1763, the English poet William Jones imagined the mythical dryad Caïssa, depicted as the goddess of chess, which has since become very popular in the world of chess. In Donald Davidson’s poem, they illustrate the theme of tradition and the importance of the past in the present. Poet Sylvia Plath uses dryads to symbolize nature in her poetry, especially in “On the Difficulty of Conjuring up a Dryad” and “On the Plethora of Dryads.

” Poets often confuse dryads, hamadryads, and nymphs.

Jack Vance (The Star King) portrayed them as beings half-human, half-tree. Explorer Lugo Tehaalt discovered them on the planet he described as a paradise.

They have a human body with branches extending from their necks and shoulders. David Eddings, in the series “The Belgariad / The Malloreon,” uses the term dryad to create a woodland people, entirely female, from which the character Ce’Nedra originates.

George Sand (Story of My Life): “I was not yet strong-minded enough not to hope at times to surprise the nymphs and dryads in the woods and meadows.”

British author C.S. Lewis mentions their presence throughout his children’s book series “The Chronicles of Narnia.” In the novel “The Last Battle,” one of them comes to die in front of the protagonist, Rilian, after her tree is cut down.

Cultural References

- Dryads appear in texts by several classical writers and poets, such as Homer, Callimachus, Statius, Ninus of Panopolis, Opian, Ovid, Pausanias, Propertius and Valerius Flaccus.

- In the Antarctic region, Dryad Lake, located in the South Shetland Islands, is named after the nymphs.

- In the ballet Don Quixote, the character has a vision of dryads with Dulcinea.

- Also mentioned throughout the book are Anne of Green Gables: in the main character’s imagination, they are part of the enchanted forest near the family home.

- They also appear in Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson book series.

- In the Harry Potter books, the bowtruckle, which protects the trees where it lives, is similar to the dryad.

- In the animated film Barbie: Fairytopia (2005), one of the characters is a dryad named Dahlia.

- In the Winx Club anime, Flora’s zodiac sign is the dryad, as she is a nature fairy and is connected to her.

- Dryads are referenced in the Fablehaven series of books, fantasy works by writer Brandon Mull and

- They also appear in the television series Charmed, Legacies and Xena: Warrior Princess.

- In the Saint Seiya: The Lost Canvas manga there is a specter of Hades named Lucus of Dryad, the celestial star of ascension. In another manga in the franchise (Saint Seiya: Saintia Sho), the dryads are Athena’s enemies.

- Dryads are also mentioned in The Witcher book series by Polish writer Andrzej Sapkowski.