In the ancient Roman Republic, from the 5th to the 1st century BCE, the economy, much like in many societies of the classical world, was primarily, if not exclusively, centered around the production and distribution of agricultural products. The majority of this production, however, was geared towards self-consumption. The aristocratic class, known as patricians, who were also the wealthiest social class during this period, consisted mainly of large landowners personally involved in managing agricultural enterprises, such as rural estates. It was only in the later Republican era that the economic influence of the equestrian class, or equites, began to rise. Unlike the patricians, the equites derived their wealth not from agriculture but from trade, industries, and finance, including tax collection and interest-bearing loans.

Economy of the Early Roman Republic (5th century BCE–3rd century BCE)

Agriculture and Livestock

During the early Republican era, the most common form of agricultural enterprise was based on small property. The landowner personally worked the land with the help of slaves or paid laborers. The small landowner cultivated a variety of products (mixed farming), but only a small portion of the agricultural products reached the market. The majority was intended for the landowner’s family needs. The primary cultivated product was wheat, with sheep dominating in animal husbandry, while cattle and horses were used for fieldwork.

Industry

Given the predominantly rural nature of the Roman economy, when referring to industry in the Republican era of ancient Rome, it means artisanal activities. The products of these activities, much like agricultural products, were often intended more for family needs than for commercialization.

Trade

Trade in the early Republican era was primarily linked to livestock and conducted through barter (the word “pecunia,” meaning money, is derived from “pecus,” meaning livestock). In Rome, weekly markets, especially the livestock market, were held in the area of the Forum Boarium, between the Aventine and the Tiber Island. In addition to the livestock and meat market, markets for vegetables (Forum olitorium) and “delicacies” (Forum cuppedinis) developed. Finally, with the growth of cities, from the mid-3rd century BCE onwards, what we might now call “commercial centers” of the time spread, mostly near the city forum: the general markets (macellum).

Currency

When the transition from barter to an initial monetary system occurred, the value of the monetary unit, consisting of a certain quantity of copper or bronze (aes rude), was established to be equal to that of a sheep or an ox. Later, aes rude was replaced by the first bronze coin, the aes grave or asse librale (initially weighing about a pound). With Rome opening up to foreign trade, especially with Magna Graecia, in the 3rd century BCE, the first silver coins appeared, initially minted by the ally Cuma (which had a mint).

Eventually, Rome itself began minting coins, producing silver coins like the Denarius and the Victoriatus and gold coins like the Aureus, alongside bronze coins (As). The Sestertius during the Republic was a small silver coin worth 1/4 of the denarius (after Augustus’s monetary reform, it was designated a copper or, more precisely, brass (orichalcum) coin). The more valuable coins were used for international transactions, while those of lesser value were used for domestic economic purposes.

The consistency of the system was maintained through fixed exchange rates: one Aureus = 25 Denarii = 100 Sestertii = 400 Asses. Throughout the Republic, the state acted with prudence and wisdom in regulating coinage (the quantity of coins issued, their weight, and their purity).

Mines

The state held a monopoly on metals and ownership of the mines.

Economy and Society: Relations Between Patricians and Plebeians

While the concept of social class is foreign to the ancient world, it can be asserted that a minority of large landowners (patres or patricians, who inherited the right to sit in the Senate from father to son) dominated over the rest of the citizens, who lacked political rights (the plebeian order or plebs). The plebs were not a homogeneous “class,” as they included not only the poor or property-less proletarians but also wealthy plebeians, small landowners, artisans, and small traders.

Rich plebeians were primarily interested in having greater political weight and accessing major public offices, while poor plebeians, burdened by economic issues, sought the abolition of debt slavery (nexum), land distributions, and subsidies from the state. The relations between plebeians and patricians were complicated by the fact that many plebeians were clients of patrician families. Since the poor had no influence and were exposed to oppression, the most destitute plebeians sought a powerful protector (patronus) among the patrician class to assist them in court and in various circumstances in exchange for votes in elections in various assemblies.

To attain political rights, the plebs engaged in a series of harsh struggles (the Conflict of the Orders) from the 5th century BCE to the 3rd century BCE.

Economy and Expansionism

The internal class conflict, coupled with overpopulation and the need to improve the conditions of the less affluent classes, ended up fostering external expansion. The conquest of new territories allowed the distribution of new lands among the plebeians (although in reality, the distributions of ager publicus mostly ended up in the hands of the wealthier landowners) and “channeled” tensions outward, stimulating social cohesion. Thanks to this impetus, the Roman Republic initiated a process of expansion and colonization that transformed it, in two centuries, into the dominant power on the Italian peninsula.

Economic and Social Changes in the Late Republican Era (2nd century BCE – 1st century BCE)

Starting with the conquests of Greek Italy in the early 3rd century BCE (particularly Taranto and Syracuse) and then those in the Mediterranean (beginning of the 2nd century BCE) until the time of Caesar, the plundering of countries such as the Kingdom of Macedonia and Greece (197 to 146 BCE), Carthage (146 BCE), the Kingdom of Pergamon bequeathed to Rome (133 BCE), the Kingdom of Pontus after campaigns against Mithridates (88–62 BCE), the Seleucid Syria conquered by Pompey (64–63 BCE), and southern and later northern Gaul by Caesar (125–50 BCE), brought into the coffers of Rome “so many spoils from opulent nations that the City was unable to contain the fruits of its victories.”

This influx of gold and works of art brought about a massive capital movement in a city that, up to that point, had been primarily tied to agricultural activity. In addition to war booty, there were war indemnities imposed on the conquered countries and new taxes levied on the provincials. This resulted not only in an increase in wages and the cost of living, with consequences especially for the poorer social class, but also led to the devaluation of the denarius. Furthermore, there was a massive influx of slaves; consider that after the conquest of Carthage, 50,000 prisoners of war were deported, and after the wars against the Cimbri and Teutones, a staggering 140,000 slaves were introduced to the city market.

Agriculture: The Crisis of Small Property and the Rise of Large Estates

Starting from the 2nd century BCE, the continuous wars of conquest ended up keeping away from Italian soil, for many years, the citizen-soldier-farmers (small landowners) who served in the Roman army. As a result, the small farms, lacking the owner (engaged in the army), could no longer yield as before, and families were no longer able to meet the tributum, the taxes that landowners had to pay to the state. Small land ownership was also in crisis due to other factors, leading to profound transformations in Italian agriculture:

- Conquests had flooded the market with a large number of prisoners of war sold at low prices as slaves, providing labor at zero cost compared to paid laborers and thus more cost-effective for wealthy landowners.

- Competition from overseas products ultimately led to the long-term decline of agricultural incomes for small Italian landowners, who lacked the capital needed to increase productivity and compete.

- The reduction in cereal production (due to the influx of foreign and provincial wheat, with little commercial interest) in favor of cultivating olive and vine plantations.

Small farmers were thus forced to sell their lands, which were increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few large landowners due to growing indebtedness. This led to a rural exodus and the proletarianization of the urban population, especially in Rome. Alternatively, they changed their rural practices, resulting in increased costs, focusing primarily on producing oil and wine. The expropriated farmers had few other job opportunities: before the Marian reforms of 107 BCE and the option to become professional soldiers, former small landowners could, if lucky, find employment as paid laborers; otherwise, they were forced to swell the ranks of the urban proletariat.

With the expansion of large estates, there was a shift from mixed farming to extensive and speculative monoculture. This involved the large-scale cultivation of a single product for profitable market sale. The cultivation of wheat was replaced by the cultivation of olive and grapevines, and the breeding of large herds of livestock to meet the growing demand for dairy products, meat, wool, and leather. Large landowners made these choices because they were more profitable: they didn’t require specialized labor, were conducive to the large-scale use of slaves, and provided easily marketable products.

Economy and Society: Division into Nobility and Populace

The almost total disappearance of small property in Rome and Italy, coupled with the management of taxes from the provinces, led to a significant enrichment of the already affluent classes. The traditional distinction between patricians and plebeians gradually gave way to the division into nobilitas and populus. Nobilitas consisted of the amalgamation of patricians and wealthy plebeians who had now joined the Senate, alongside the ancient noble families, in governing the state and sharing all major public offices.

The main threat faced by the 300 families controlling the Senate did not come so much from tensions with the populus (consider the failure of the social and economic reform attempts by the Gracchi brothers between 133 BCE and 121 BCE) but rather from the influence of prominent personalities (Mari, Sulla, Crassus, Pompey, Caesar, and Mark Antony) attempting to exploit their prestige and sway over the army and populus to impose personal policies. This attempt was successful with Octavian, who, from 31 BCE, initiated the imperial phase of Rome’s history.

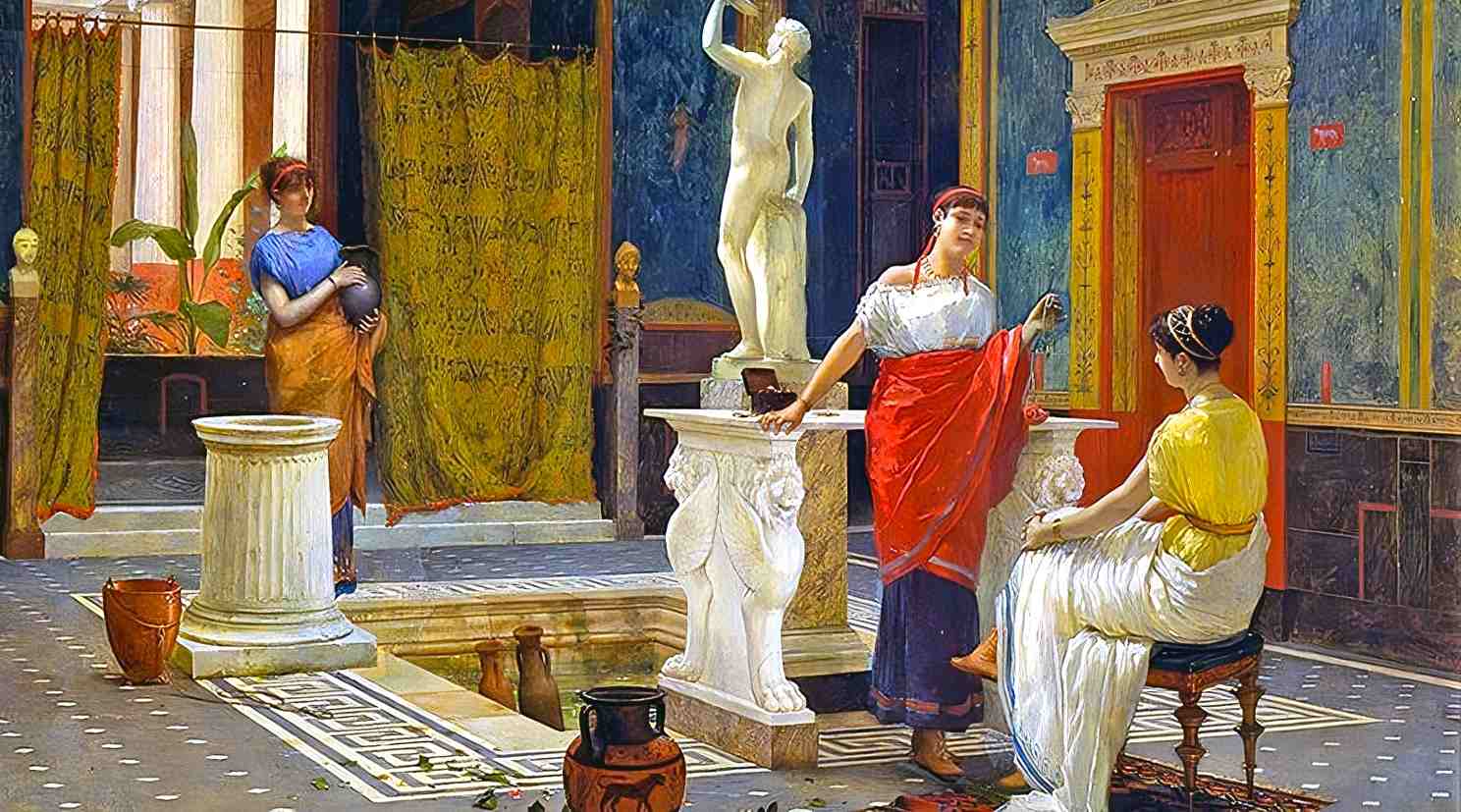

Much of the lavish spending by the rich was not focused on luxury but rather served as a “political” investment. Consuls, magistrates, military leaders, and dictators lavished the people with spectacular festivals and games, extraordinary gratuities to their legions, and constructed forums and theaters for the Roman people in exchange for votes, further fueling their “generosity.” Votes could also be directly purchased (it is said that at certain times, the price of votes was posted in thermopolia, the bars of that era).

Industry, Trade, and Mines in the Hands of the Equites

In the 2nd century BCE, alongside the senatorial aristocracy, a new social group distinct from the nobilitas and populus emerged. This group, known as equites or knights, comprised those who could maintain at least one horse and serve in the cavalry. However, the term came to designate wealthy individuals not belonging to the senatorial class.

As senators were traditionally forbidden from engaging in commerce, it was the knights who became entrepreneurs, contractors, and merchants (negotiatores), specializing in industrial and commercial activities. They achieved enormous profits, enabling them to acquire immense prestige and influence. Many of their businesses depended on activities performed for the state: supplying clothing, weapons, and provisions to legions; constructing roads, aqueducts, and public buildings; exploiting mines; lending money at interest (argentari); and collecting taxes and vectigalia (publicans).

References