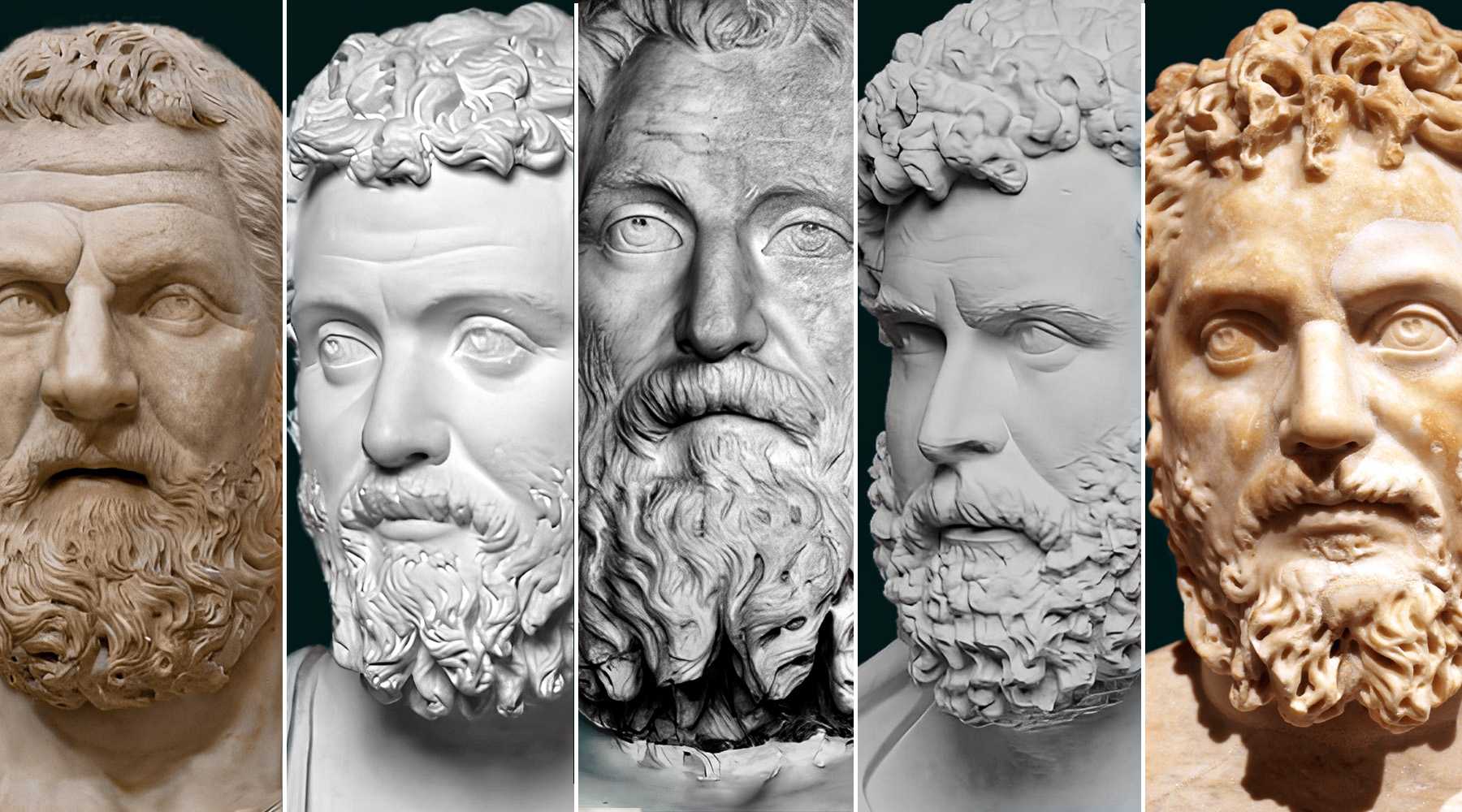

Edict of Milan: Religious Harmony in the Roman Empire

Emperor Constantine I issued the Edict of Milan during his reign, which guaranteed the right of all citizens to practice any religion they wished. This decision had a significant impact on the expansion of Christianity in the Roman Empire during the fourth century."