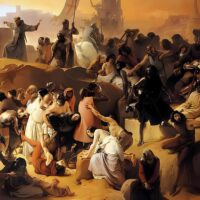

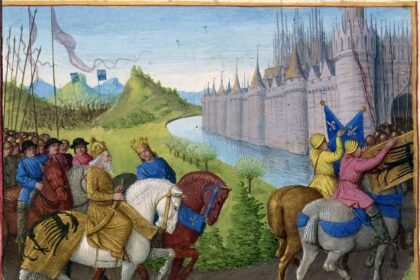

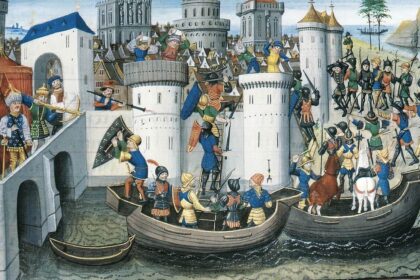

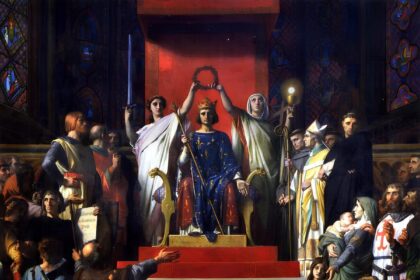

Eighth Crusade (1270)

The Eighth Crusade (1270) was the last of the major Crusades launched to the Holy Land, though it did not target Jerusalem directly. It was initiated by King Louis IX of France, who had previously led the Seventh Crusade (1248–1254), and it ended in failure.