It was in Etruria, on the Italian peninsula, that the ancient Etruscans created their advanced civilization. Ancient Tuscany was once known as Etrusci or Tusci by the Romans. Etruria had its zenith between the eighth and fifth centuries BC, when it ruled over Latium, Campania, and the Po Valley; but, by the third century BC, it had been totally conquered by Rome. The tomb paintings and vase embellishments were only two examples of the Etruscans’ artistic and craftmanship prowess; sculptors created bronze and terracotta works, and the competence of the jewelers and metalworkers was attested to by the tombs themselves.

The origins and settlement of the Etruscan people

To this day, historians could only speculate on where the Etruscans came from. There had always been debate among historians over the origins of the people who settled what was now Tuscany in northern Italy. Herodotus was among those who claimed they originated in Asia Minor. Another theory suggests that the Etruscans were an Indo-European population who migrated to Italy across the Alps, whereas the Villanovan civilization’s proponents claim they were an indigenous people already living there. The notion of an oriental origin, which still had its advocates today, had mostly faded away, despite the fact that the Etruscans and the civilizations of Asia Minor were culturally and linguistically close.

It was likely that the emergence of this power was in reality due to numerous mutations and external influences, but thanks to the excavations carried out in actual Tuscany since the XVIIIth century, we can now attest to the presence of this civilization in the Iron Age, from the end of the Xth century BC.

In the beginning, the Etruscans established themselves in the region around the Thyrrenian Sea, where they built the city of Tarquinia. In the seventh century BC, the Etruscans’ domain extended from the north and east to the west and south to the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Tiber. Its fleet was formidable, and its sailors were among the best in the world, so they were soon able to contend with the Greeks and Carthaginians for control of the western Mediterranean.

Because of the danger posed by the Greeks, they allied with the Carthaginians, and, in 540 BC, they conquered Alalia and expanded their territory to Campania. Meanwhile, the Carthaginians occupied Sicily and Spain. Lattara, in what was once Celtic Gaul, became an Etruscan colony (Lattes, near Montpelier). A life-sized figure of an Etruscan warrior, together with a sanctuary and ancient graves, were uncovered in 2002.

The political and religious organization of Etruscans

The Etruscans organized themselves into city-states, often in groups of 12 (dodecapoles), bound together primarily by religion rather than politics. Each one was an independent thinker, yet none of them took the lead. The failure of the Etruscan towns to unify at a crucial time ensured that they would fall one by one under Roman dominance, and their independence was a major contributing factor to their eventual demise. Many of the Etruscan rulers who controlled Rome have been identified according to Roman mythology. Etruscan elites remained in power until the civilisation was completely destroyed, even after Rome had become a republic at the end of the sixth century.

Kings called lucumons ruled the towns with the aid of crowns, thrones, sceptres, and purple robes until the fifth century BC. As these monarchs fell from power, they were replaced by nobles who divided up the spoils among themselves. The demographic structure and the magistracies below the highest level were mostly unknown, but we do know that there were a lot of slaves there.

Given the descriptions of violent uprisings, it was safe to assume that some of these people were in dire straits. Other people, like most free males, were allowed to live in their own homes. However, without any physical remains, depicting these Etruscan dwellings was challenging. On the other hand, Etruscan women had the same social status as their male counterparts. She could take part in banquets, in sporting competitions, and even in performances.

Not far from the towns were the huge necropolises. The tumuli, surmounting subterranean burial chambers, were the principal source of information for archaeologists. These rooms, which were discovered in the nineteenth century, were meant to be representations of the deceased’s household life and included items like food, vases, jewels, and even frescoed walls in the most lavish tombs.

The Etruscans believed that the dead should have a feast, games, and dances to help them on their path to the afterlife. These lavish details speak to the affluence of this society, which Posidonios claims had enough of both food and fine garments. As a result, this culture is distinguished by an emphasis on life’s ecstatic joys and an extravagant display of wealth.

Only the names of a few deities, such as Ata, ruler of the Underworld (Hades), and Tinia, ultimate God, were accessible to us from Etruscan religious tradition (Zeus). According to Livy, the Etruscans “wanted to practice religious ceremonies more than any other country.” This fact had been verified by archaeologists. Therefore, the Etruscans were ritualistic people who were fascinated with the occult and otherworldly.

Etruscan army

The exact way the Etruscan military was structured was a mystery to modern scholars, and the censal reform mentioned by Tite-Lice would be a later development, occurring after the reign of Servius Tullius.

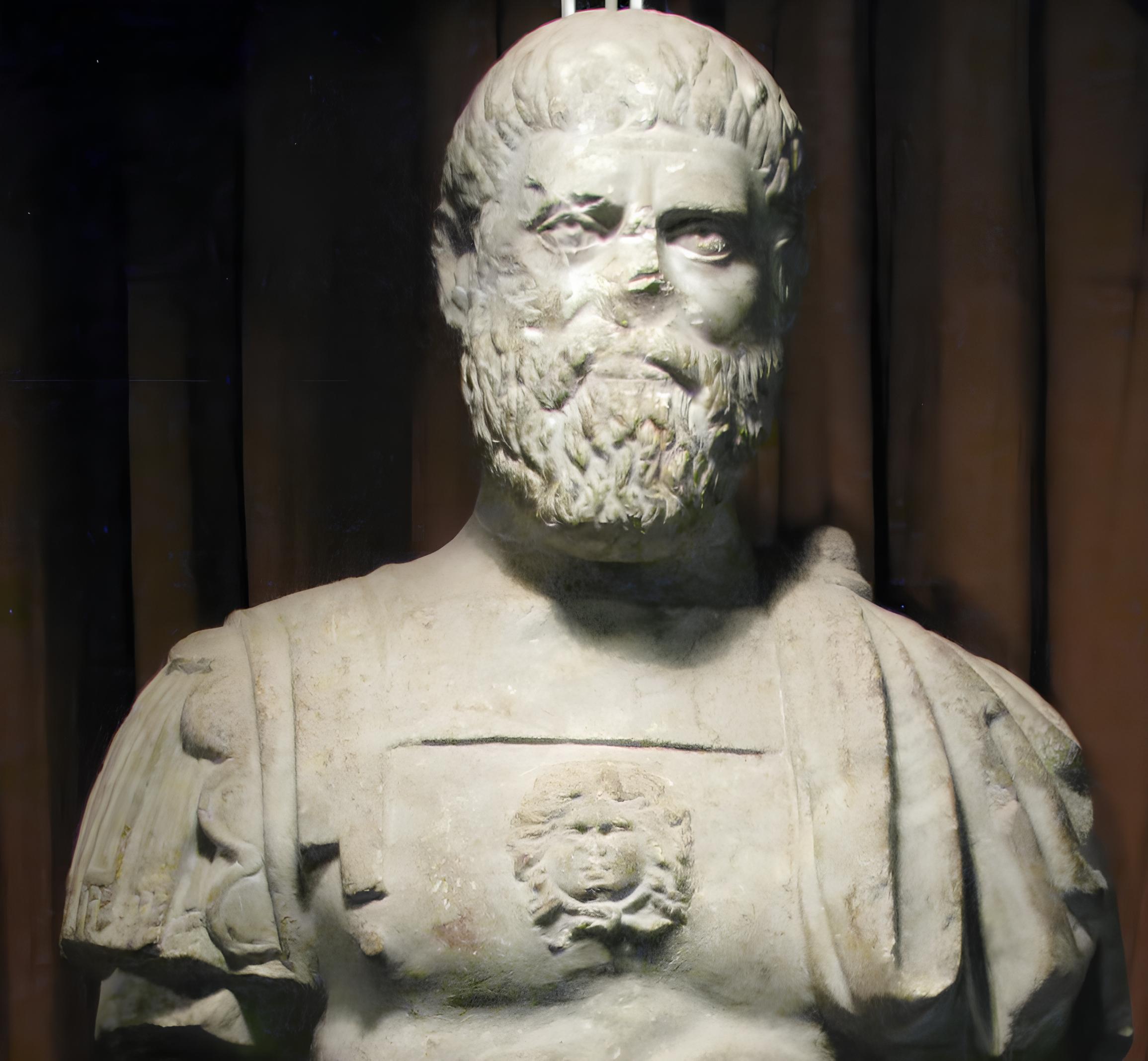

The conflict at first seemed to be more of a tale of territorial disputes. The Etruscan towns and political developments of the seventh century saw the establishment of a standing army, with its soldiers equipped similarly to the Greek hoplites and trained to battle in phalanx formation. The hoplites, who wore bronze armor and fought in phalanxes behind their massive circular shields called clipeus, were the first of the army’s three components (helmet, cuirass and bronze leggings, spear and sword).

The men in the second row battle with less heavy weaponry, including helmets, scutums, and lances. When the trumpeters give the signal, the third line of voltigeurs, velites, and slingers charges forward to annoy the adversary before retreating. Tanks were probably not utilized in battle by the Etruscan army, despite the fact that they possessed a cavalry, unlike the Greek army. Due to the high price of military hardware, however, there were disparities in the level of weaponry across troops.

The Ancient Roman and Etruscan monarch, Servius Tullius, was well known for modernizing the Roman military. Based on their cens (monetary value), he planned to divide the populace into five strata. Given that the wealthy will be able to afford to help defend the city with more sophisticated weapons, this provision will alter the structure of the military. The helmet with a spherical cap, neck cover, and cheek guards seemed to be imposed on the upper classes in the fourth century BC, while the lower classes continued to use the hoplitic panoply.

Etruscans sciences

The Etruscans understood the human body well. Archaeological digs have uncovered temples with anatomical replicas, a testament to the civilization’s level of understanding of the subject, as well as several surgical implements. They were proficient at cranial trepanation and the implantation of gold dentures (found on some human remains).

Etruscologists believe that the wax or clay artifacts depicting internal organs like the heart, lungs, or uterus were meant as gifts to the Gods in the hope that the Gods would help cure the ill portion of the body depicted in the artifact. The Etruscans understood the healing potential of thermal waters, and they employed them in potions to treat a wide variety of illnesses.

Etruscan language

If communication in Etruscan was difficult, at least the written form should be easier to read. It’s purely alphabetic, with no ideographic symbols at all. This was an alphabet that was unquestionably derived from the Greek language, and it was read from right to left. About 10,000 inscriptions have been preserved; most of them date to Roman times and were found in the regions of Campania, Lazio, and Tarquinia. Most of these inscriptions date back to the 5th century BC and are either funeral or votive in nature, such as the inscription on a mummy strip kept in Zagreb or the golden tablets of Pyrgi.

It is unclear when Volnius lived, but he wrote religious and literary works, notably the Tuscan plays. Despite having been translated into Latin, many of these papers have vanished.

This culture was also distinguished by its extensive artistic legacy. The tomb paintings and vase decorations are only two examples of the Etruscans’ artistic and craftsmanship prowess; sculptors of the time created works of bronze and terracotta, and the jewelry and metalwork found in their graves are a living testament to their excellence.

Etruscan architecture: Rare remains

Palaces, civic buildings, and early temples were all constructed of wood and brick, but now not a single one of them stands. Much like their Greek counterparts, temples were enclosed inside walls and had tiled gabled roofs supported by columns, much like their ceramic votive models and remnants of later stone constructions.

An Etruscan temple, on the other hand, was constructed on a north-south axis and stood on a platform with a four-columned porch facing three doorways leading to three parallel rooms for the three major Etruscan gods, as opposed to the Greek temple, which was built on an east-west axis on a low median, accessible from all four sides by a colonnade. Tile seams and the ends of the rafters were hidden by vividly colored clay figurines that adorned the ceiling. The entablature was adorned with bas-relief sculptures of humans. The Romans adopted the Etruscan design for their temples.

Like the Greek acropolis, most Etruscan towns were built on hills and were laid out in a quadrilateral fashion, complete with defences and enclosures that were strengthened with double doors and towers. It was believed that the walls of ancient Rome, constructed during the reign of Servius Tullius (578–534 BC), were erected according to Etruscan design principles.

The interiors of tombs and house-shaped burial urns hint that Etruscan homes had one to three rooms, a flat or sloping tile roof, and a fireplace, but no surviving examples of these structures have been located. Later versions used the Roman system of an atrium with an open roof over a cistern for rainfall and a loggia. The Etruscans constructed aqueducts, bridges, and sewers, including the Tarquin-built Cloaca maxima in Rome.

Etruscan art

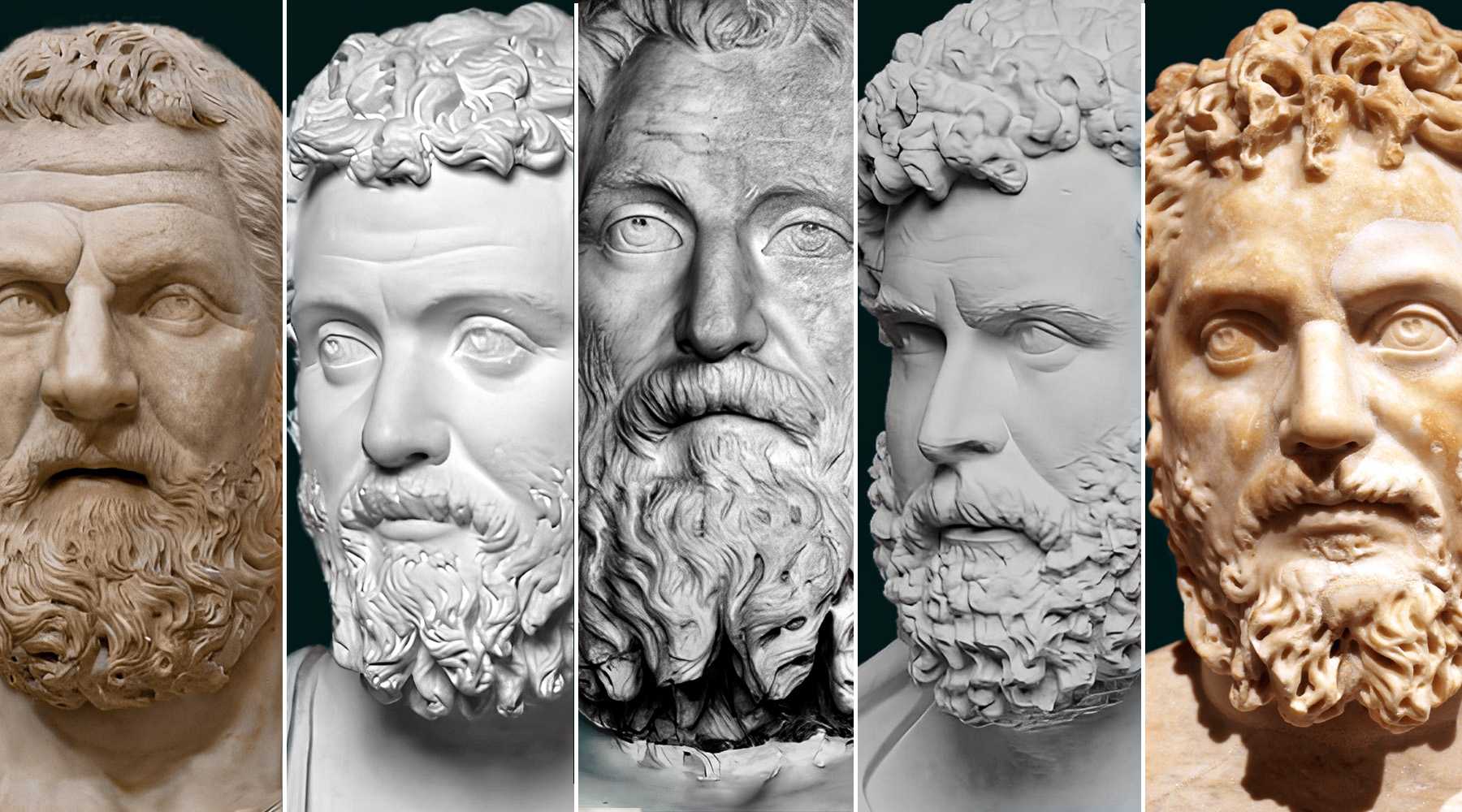

Sculptures

Like other ancient civilizations, the Etruscans did not appreciate art for its own sake but rather made artifacts for practical or spiritual purposes. Since no artists’ names have been documented, there has been a dearth of purely civic public artwork. The political autonomy of the several Etruscan cities is reflected in the fact that their art had similarities but also distinct features.

The most well-known pieces of Etruscan art were made of terracotta, and they were either sculptures found on the covers of sarcophagi (the “sarcophagi of the spouses,” end of the sixth century BC, Villa Giulia, Rome) or works for the temples, such as covers to protect the wood and the sculptures on the roofs and pediments. The carvings of the Sphinx and the winged Lion of Rome were only two examples of the mastery with which the artisans of Vulci worked the local limestone, nenfro.

The She-wolf of the Capitol (c. 500 BC), Chimera (5th–4th century BC, Archaeological Museum, Florence) from Arretium, and the life-size statue of Aulus Metellus as an orator, known as the Arringatore (1st century BC, Archaeological Museum, Florence), were the most beautiful bronze achievements of this period.

Painting

Frescoes on stone or plaster were the most common type of Etruscan art, and they were often seen adorning the walls and ceilings of tombs, particularly in Tarquinia and the area around Clusium. There are also a few painted panels that have been kept. The ancient era was characterized by vibrant paintings with active lines and crisp, vivid colors. There was a lot of dark emphasis on the stylized, colossal forms.

The four Caere slabs (c. 550 BC; British Museum, London) depict religious situations, whereas the scenes in the Tomb of the Bulls (530–520 BC; Tarquinia) were taken from Greek literature. The majority of them were depictions of real-life events, such as the games, dances, and banquets that were often held in conjunction with funerals (Tomb of the Augurs 520-510 BC; Tomb of the Triclinium 480-470 BC).

War images abound in Vulci (near Tarquinia), and fearsome demons from the country of the dead (Tomb of the Ogre, 2nd century BC ), in the tombs from the 4th century forward, which were influenced by Hellenistic art and the loss of Etruscan authority and were unexpectedly ominous.

Decorative arts

In addition to importing and copying Greek pottery with decorative motifs, the Etruscans also invented a method for creating bucchero items, which were characterized by their glossy black surface and intricate relief incisions meant to evoke the work of metalworkers. This method flourished after the seventh century BC and through the sixth century.

The Etruscans worked bronze into chariots, vases, candelabra, cylindrical chests, and polished mirrors, all lavishly etched with mythical patterns. Jewelry was crafted in gold, silver, and ivory using techniques including filigree and granulation.

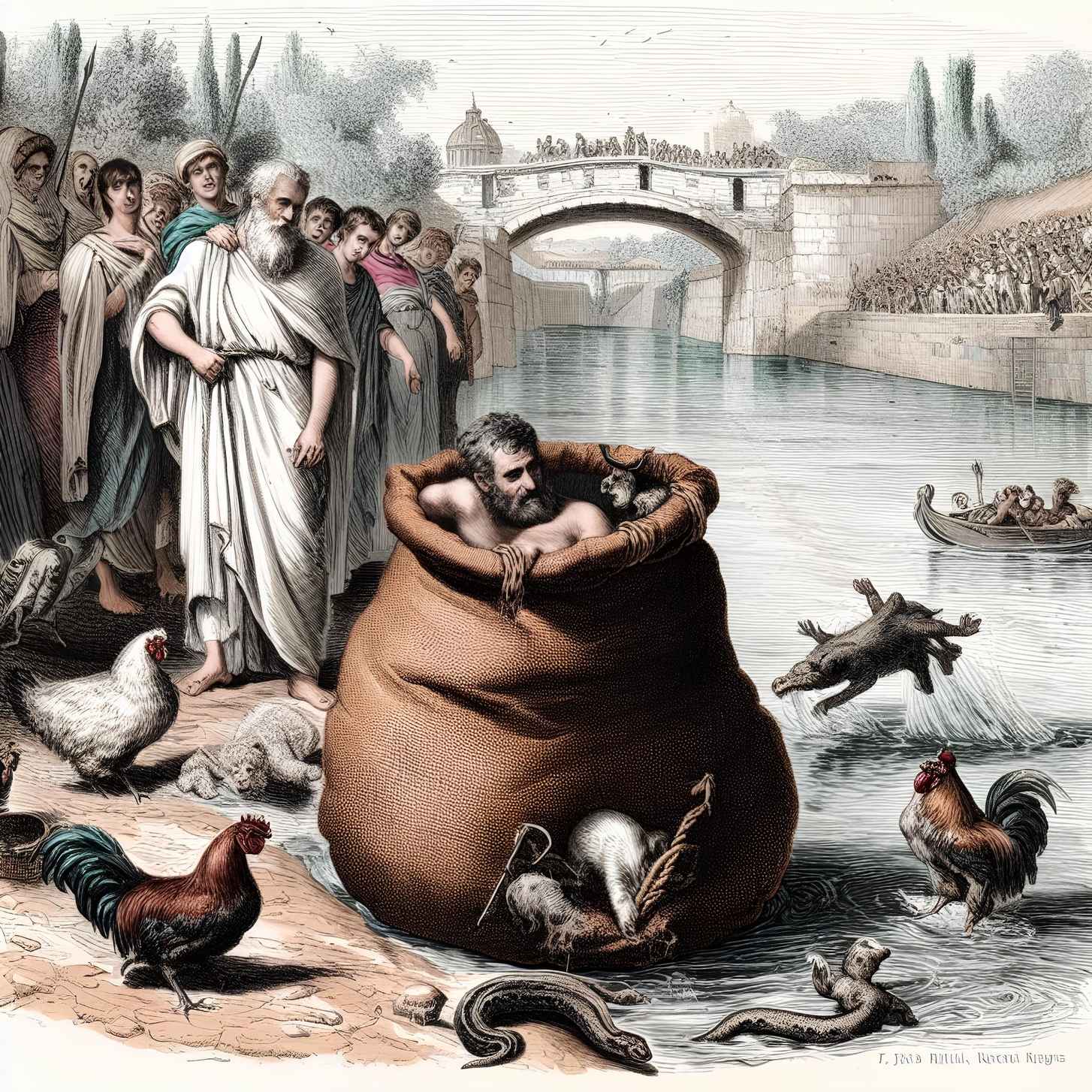

The end of the Etruscan civilization

Starting in the early 500s BC, a coalition of Latin peoples, bolstered by the Greek army of Cumae, defeated the Etruscans. At the same time as the Roman Republic grows in prominence, the Etruscan civilization begins to fall apart after losing to the Greeks in 474 BC. The Roman army gradually conquered the region, and in 264 BC, when they finally captured the Etruscan stronghold of Volsinies, the Etruscans as a civilization were obliterated forever.

Efforts at an uprising against the Roman authorities were swiftly put down. In the first century BC, when the Etruscans became Roman citizens, links between the two regions became stronger. But their elevated position lasted only until they joined the losing side in the civil wars (88-86 BC and 83 BC). Sylla, the conqueror, exacted a bloody vengeance on the Etruscans by destroying towns, stealing land, and restricting their freedoms.

The destruction wreaked by Sylla’s savagery on Etruria rendered succeeding uprisings futile. The Romanization of Etruria was hastened by the arrival of fresh immigrants dispatched by Augustus. Whatever happens to Etruria politically, its religions, superstitions, arts, and practices will live on in Roman culture.

Bibliography:

- De Grummond, Nancy T. (2014). “Ethnicity and the Etruscans”. In McInerney, Jeremy (ed.). A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 405–422. doi:10.1002/9781118834312. ISBN 9781444337341.

- Shipley, Lucy (2017). “Where is home?”. The Etruscans: Lost Civilizations. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 28–46. ISBN 9781780238623.

- Pallottino, Massimo (1947). L’origine degli Etruschi (in Italian). Rome: Tumminelli.

- Mauro Cristofani, Introduction to the study of the Etruscan, Leo S. Olschki, 1991.

- Spivey, Nigel (1997). Etruscan Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Romolo A. Staccioli, The “mystery” of the Etruscan language, Newton & Compton publishers, Rome, 1977.