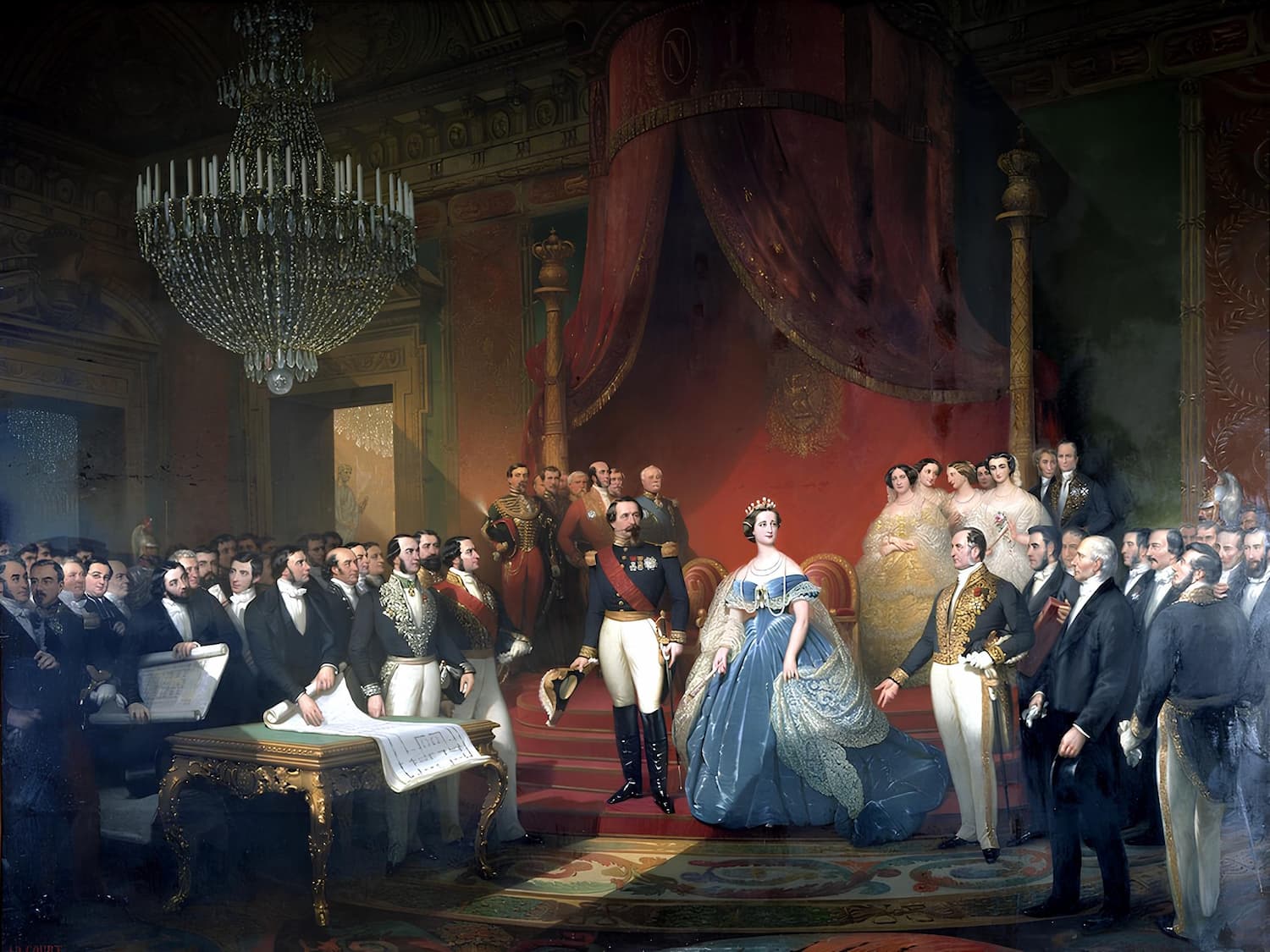

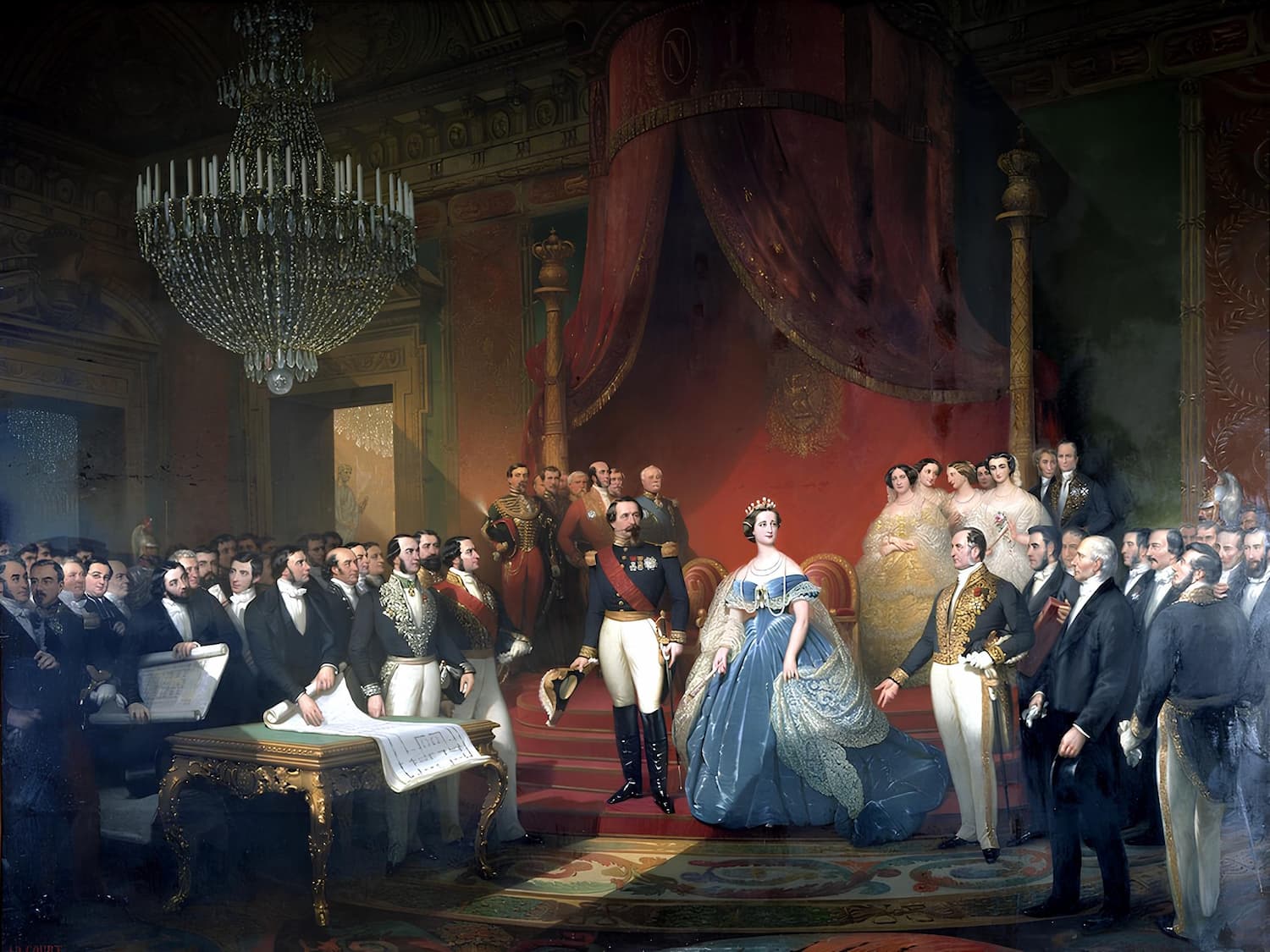

Eugénie de Montijo: The Stylish Empress of Napoleon III’s France

Eugénie de Montijo was a Spanish noblewoman who became the Empress of the French as the wife of Napoleon III. She was born on May 5, 1826, in Granada, Spain.

Eugénie de Montijo was a Spanish noblewoman who became the Empress of the French as the wife of Napoleon III. She was born on May 5, 1826, in Granada, Spain.