- Nevsky Began to Rule When He Was Very Young

- He Was Cruel and Merciless: He Cut Off Noses and Gouged Out Eyes

- He Was Called Nevsky During His Lifetime

- He Favored Peace With the Horde

- He Betrayed the Russian Principalities

- He Said, “Whoever Comes to Us With a Sword Will Perish by the Sword”

- Nevsky Never Lost a Battle

- He Won the Battle on the Ice Because the Germans Wore Very Heavy Armor

- The Battle on the Ice Never Happened

- Alexander Nevsky Corresponded With the Pope

- Before His Death, He Took Monastic Vows

Nevsky Began to Rule When He Was Very Young

Verdict: Partly true

In Rus, the adult life of princes and other noble people began very early. When Alexander was seven years old, he and his older brother, Fyodor, became deputies for their father, Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, in Novgorod. However, at that time, the affairs were actually managed by the boyar Fyodor Danilovich and the steward Yakim, who were left with the children. Alexander truly began to rule at the age of 26, after his father’s death.

He Was Cruel and Merciless: He Cut Off Noses and Gouged Out Eyes

Verdict: True

In the Middle Ages, human rights were perceived very differently than they are today; the lives of commoners were of little value. After liberating the captured fortress of Koporye in 1241, the prince took the knights of the Livonian Order prisoner and brought them to Novgorod. Alexander hanged the local residents who had submitted to the knights as a warning. During his campaign in the territory of the Bishopric of Dorpat in 1242, he allowed his soldiers to “live off the land,” meaning to plunder the farmers and fishermen living in enemy territory.

His opponents and other princes of that era also fought in this manner.

However, in 1257, when his son Vasily, who was then the prince of Novgorod, refused to pay tribute to the Tatars and fled to Pskov, Alexander indeed dealt harshly with his servants: “Some had their noses cut off, while others had their eyes gouged out.” This was a very severe punishment, but the situation was also dangerous: unrest had begun in Novgorod. The mayor, Mikhalko Stepanovich, was killed, and the Lithuanians launched a successful raid on the city of Torzhok, a major trading hub on the way to Novgorod from the southern regions of Rus.

He Was Called Nevsky During His Lifetime

Verdict: False

The Battle of the Neva in 1240 between the Swedish and Novgorodian armies was indeed a significant victory for the prince, but the nickname “Nevsky” first appeared in a text titled “And These Are the Russian Princes” from the early 15th century. It began to be widely used even later, after Alexander’s canonization in 1547.

The nickname was finally established under Peter I, who moved the prince’s relics from Vladimir to Saint Petersburg. This was a symbol of the old victory over Sweden, with which Peter was at war. The emperor also ordered the commemoration day of Alexander Nevsky to be moved from November 23 to August 30, which was the day the victorious Treaty of Nystad was signed, ending the Great Northern War (1700–1721) between the Swedish Empire and a coalition of Northern European states (including Russia) for control over the Baltic lands and dominance in the Baltic Sea.

He Favored Peace With the Horde

Verdict: True

During the campaigns of Khan Batu against Rus in 1237–1238 and 1239–1240, as well as in the initial period after them, the young Alexander did not make any decisions; the senior princes — Mikhail of Chernigov, Daniil of Galicia, and Alexander’s father, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich — were in charge. The first soon died in the Horde, the second unsuccessfully sought help from the West, and the third eventually recognized the Khan’s authority.

Alexander’s brother, Andrei, tried to resist and had to flee to Sweden from a punitive expedition known as the “Nevryu’s Raid.” Alexander did not enter into conflict with the Horde. He was unlikely to have been pleased by this, but politics is a harsh affair. Moreover, he lacked the strength to oppose the Mongol Empire.

He Betrayed the Russian Principalities

Verdict: False

Alexander could be cruel, but it is unlikely he can be called a traitor who willingly entered the service of the conquerors. The legend that Khan Batu made the prince his “adopted son” and even heir to the Golden Horde is a fiction by Soviet writer Alexei Yugov, author of the novel “The Warriors.” Historian Lev Gumilev also claimed, without evidence, that Alexander even became a blood brother to the Khan’s son Sartaq.

There is an opinion that in 1252, Alexander went to the Horde with a complaint or denunciation against his brother Andrei — and that Nevryu’s campaign was a result of this. Historian Vasily Tatishchev wrote about this in the 18th century:

Alexander complained about his brother, the Grand Prince Andrei, saying he had deceived the Khan, took the grand principality under himself as the elder, seized the ancestral cities, and did not pay the Khan taxes and customs in full.

But it’s hard to trust this account: we do not know on what basis it was written. Moreover, there is nothing about it in other sources.

Like other princes, Alexander obeyed the Khan’s will, went to the Horde, paid tribute, and received a label to rule. Relying on the Novgorodian nobility, he forced the townspeople to comply with the Tatar census and the need to pay the Khan. Acting otherwise was impossible; otherwise, he would have had to flee, and a more compliant prince would have carried out the census (along with a punitive expedition).

He Said, “Whoever Comes to Us With a Sword Will Perish by the Sword”

Verdict: False

In the few surviving chronicles that recount Alexander’s battles with the Germans, there is no mention of such a speech. This legend most likely arose after the release of Sergei Eisenstein’s famous film “Alexander Nevsky,” in which the main character loosely quotes the Gospel of Matthew: “Then said Jesus unto him, Put up again thy sword into his place: for all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.”

Nevsky Never Lost a Battle

Verdict: True

Prince Alexander Nevsky was raised from an early age to be a future warrior, accompanying his father on campaigns even as a child. In 1235, fourteen-year-old Alexander participated in the Battle on the Emajõgi River (in present-day Estonia), where the forces of Yaroslav Vsevolodovich defeated the Germans.

In addition to his well-known victories in the Battle of the Neva and the Battle on the Ice, the prince successfully repelled raids by Lithuanian leaders and in 1256 led a large campaign into Finland: “He came to the land of the Yem, some were killed, others captured; and the Novgorodians returned with Prince Alexander all in good health.”

He Won the Battle on the Ice Because the Germans Wore Very Heavy Armor

Verdict: False

The equipment of a fully armed cavalry warrior of that era (whether a knight of the Livonian Order or a princely retainer) was roughly the same, including in weight. Both sides had heavily and lightly armed warriors.

In reality, victory was achieved through a well-executed tactical maneuver and the effective distribution of forces.

According to various German sources, several dozen German knights were killed or captured on the battlefield—a significant loss for that time.

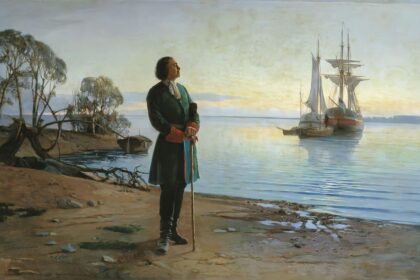

The Battle on the Ice Never Happened

Verdict: False

Image: Public Domain

The battle is documented in both Russian chronicles and the German “Livonian Rhymed Chronicle” of the 13th century. Although the anonymous German author praised the deeds of the “God’s knights” of the Livonian Order and downplayed their defeat, he did not deny the fact that the battle occurred and that the Russians were victorious. However, it was not an epochal battle that changed the fate of nations, even though more than a thousand and possibly several thousand people participated.

On the Russian-Livonian border, armed clashes and large-scale campaigns against each other were common. The forces of the Livonian Order often besieged Pskov, while Russian princes, in turn, led troops deep into German territories. For example, Svyatoslav and Mikhail Yaroslavich, together with the Pereyaslavl militia under the command of Dmitry Alexandrovich, the prince’s son, defeated a combined army of Danes and the Livonian Order.

Alexander Nevsky Corresponded With the Pope

Verdict: True

The prince did indeed correspond with Pope Innocent IV. For example, in a letter from January 1248, the Pope praised Alexander’s wisdom, his adherence to Christianity, and his refusal to serve “Tatar barbarians.” Interestingly, Alexander was preparing to travel to the Horde at that time.

In another letter, Innocent IV expressed joy that the prince had agreed to convert to Catholicism and build a “cathedral for the Latins” in Pskov. It seems the Pope misunderstood one of Alexander’s letters, which, unfortunately, has not survived. While in the court of Khan Batu, the prince sent a firm refusal to the Pope: “…we do not accept your teachings.”

Before His Death, He Took Monastic Vows

Verdict: True

The prince took monastic vows under the name Alexius, and in 1547 he was canonized as a saint, revered as a monk, a righteous prince, and the ancestor of Moscow’s rulers. However, starting in the 18th century, the Synod banned depictions of Alexander in monastic attire: Peter I ordered that he be honored specifically as a warrior-ruler.