Beethoven Grew Up in a Poor, Dysfunctional Family

Verdict: This is partly true.

- Beethoven Grew Up in a Poor, Dysfunctional Family

- Beethoven’s Father Wanted to Make Money by Turning His Son Into a Second Mozart

- Beethoven Was Poorly Educated Because He Did Not Attend School

- Beethoven Added the Particle “van” to His Surname to Appear Aristocratic

- Beethoven Was Deaf

- He Composed Strange Music That Nobody Listened To

- Beethoven Supported Napoleon and Dedicated His Third Symphony to Him

- Beethoven Was Unhappy in Love

- Beethoven Did Not Wear a Wig as a Protest Against Social Norms

- Beethoven’s Music Inspired Lenin’s Revolution

- Beethoven Constantly Changed Apartments While Living in Vienna: More Than Seventy in Total

- Beethoven Loved Beer

- Beethoven Suffered from Bipolar Disorder

- Beethoven Died in Poverty

Ludwig van Beethoven was indeed born into a poor family. The family lived in Bonn; his father, Johann Beethoven, was a singer in the court chapel of the Elector of Cologne and earned about 315 florins a year, which was barely enough for food and rent. A small additional income came from private lessons: Johann taught piano, violin, and viola. He was a professional musician and was invited to perform in wealthy households.

Johann Beethoven married Ludwig’s mother, Maria Magdalena, for love, but his own father, the Kapellmeister of the Bonn court chapel, considered this marriage a misalliance and cut off his son’s financial support. He softened only when his grandson was born, who was named Ludwig in honor of his grandfather.

In 1787, Maria Magdalena died of tuberculosis. The myth of syphilis, which supposedly afflicted both the composer’s mother and father, and even Beethoven himself, emerged later and has no evidence to support it. Allegedly, this was why the composer’s older brothers were born blind, deaf, or with developmental disabilities. In reality, Beethoven was the second child in the family: his older brother died shortly after birth. No records suggest that any children in the Beethoven family were born with congenital defects.

After his wife and younger daughter died, Beethoven’s father indeed began to have problems with alcohol: seventeen-year-old Ludwig often had to drag him out of the police station.

Beethoven’s Father Wanted to Make Money by Turning His Son Into a Second Mozart

Verdict: This is true.

The phenomenon of Mozart did not leave many parents at peace. When Ludwig was 3–4 years old, his father noticed his musical abilities and decided to use them to improve the family’s financial situation. At the same time, he admired his son’s abilities and said, ““In my son Ludwig I now have my only joy. He’s progressing so well in music and composition that he’ll be regarded by all with amazement. My Ludwig, my Ludwig, I know it! In time he’ll become a great man in the world. Those of us gathered here, and now witnessing it, remember my words!.” However, unlike Leopold Mozart, the composer’s father, Johann did not possess teaching talent and, instead of support and praise, resorted to punishment. Beethoven recalled that he and his younger brothers were raised with beatings, a common practice at the time.

Starting at around four years old, Ludwig played the piano, violin, and viola for long periods every day. He couldn’t reach the keyboard, so he had to stand on a bench. Playing string instruments never quite worked out for him, although he later tried to learn.

Beethoven’s first public concert took place on March 26, 1778, in Cologne, where he was presented as a six-year-old virtuoso, even though he was already over seven. However, the concert, like subsequent tours in the Netherlands, did not bring money or fame. The audience might have expected improvisations and musical tricks that amazed them with young Mozart, but Johann did not consider this important: unlike Mozart, Ludwig was forbidden to improvise. Hearing live music, his father would exclaim, “Why are you tinkering again? Get out, or you’ll get a slap!”

Beethoven Was Poorly Educated Because He Did Not Attend School

Verdict: This is partly true.

Beethoven did not receive a systematic school education. He briefly attended a private school and a monastery, but without much success. The teaching methods involved drilling, rote learning of catechism, and Latin, which provoked resistance in the boy. Moreover, his father believed that school was a waste of time.

As an adult, Beethoven tried to fill the gaps in his education. He studied French and Italian, learned history, astronomy, and philosophy. In 1789, eighteen-year-old Ludwig even became a student at the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Bonn. He was fascinated by ancient literature, loved Goethe, Schiller, Herder, Shakespeare, and many other authors. However, he never mastered mathematics, only learning addition and subtraction, and wrote with errors.

His musical education was also unsystematic, but Beethoven was fortunate with his teachers (aside from his father), who also acted as his promoters. One of his first teachers in Bonn was Christian Gottlob Neefe, a renowned German composer and organist. After moving to Vienna, Beethoven studied with other famous musicians.

Joseph Haydn not only taught him music but also helped him enter Viennese society and lent him money. Antonio Salieri taught him to compose vocal music in the Italian style. Beethoven also highly valued his lessons with the composer Johann Georg Albrechtsberger. According to a contemporary, the Viennese teachers had this to say about their student:

All three held Beethoven in high esteem but were unanimous in their opinion of his studies. Each said: Beethoven was so willful and stubborn that he had to learn from his own bitter experience what he would never accept as a subject of study.

Beethoven himself confessed to publisher Gottfried Härtel:

There is no treatise that is too scholarly for me. Without claiming actual scholarship, from childhood, I have strived to comprehend the best and the wise produced by each era. Shame on an artist who does not consider this mandatory, at least within their power.

Beethoven Added the Particle “van” to His Surname to Appear Aristocratic

Verdict: This is not true.

The particle “van” before Beethoven’s surname (Beethoven literally translates to “beet garden”) actually meant that his family originated from the town of Beto, or Betuwe, in Flanders. Contemporaries from other countries might have mistaken “van” for the equivalent of the German “von,” which indicated noble origin.

Once, Beethoven tried to use this to his advantage. When a court dispute arose between the composer and his sister-in-law over the guardianship of his nephew Karl, Beethoven argued in favor of his claim to belong to the upper Dutch class using the “van” particle. However, he could not provide documentary proof, so the land court, which handled noble disputes, referred the case to the Vienna Magistrate, which dealt with the affairs of common citizens. Beethoven was outraged: “In the Netherlands, they would have shown better awareness of this insignificant significance.”

Beethoven Was Deaf

Verdict: This is almost true.

Beethoven began to lose his hearing gradually: the first signs of deafness appeared when he was 28 years old. It might have been caused by an illness he had suffered a year earlier. He experienced painful sensations, noises, and ringing in his ears, gradually losing the ability to hear soft, high-pitched sounds.

In April 1802, he went to the resort of Heiligenstadt, near Vienna, for treatment. There, he fell into a depression and contemplated suicide. In a confession known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, he spoke about the “burning fear” of people, the fear of being exposed for his affliction, and his cruel fate. Fortunately, it did not come to suicide.

Despite his progressive illness, Beethoven continued to perform as a pianist, and between 1806 and 1814 as a conductor. He sometimes improvised in private salons. Almost complete deafness set in around 1818, nine years before his death. The composer communicated with others by writing down replies in notebooks that he constantly carried with him.

He Composed Strange Music That Nobody Listened To

Verdict: This is partly true.

To Beethoven’s contemporaries, his music seemed complex and incomprehensible, and some even saw it as “aesthetic and artistic terrorism.” He indeed did not write for the general public but for educated people from high society, yet he was not always understood by them. For instance, Emperor Franz, known for his reactionary reforms, disliked his music because he believed it destroyed traditions.

However, Beethoven had many admirers, such as the Russian Prince Nikolai Borisovich Golitsyn. Golitsyn wrote to Beethoven about the Missa Solemnis, whose world premiere, with his support, took place in St. Petersburg in the spring of 1824:

…the entire composition is a treasure trove of beauty, and it can be said that your genius has surpassed the ages, and that perhaps there are not yet sufficiently enlightened listeners who can fully appreciate the beauty of your music. However, your descendants will honor and bless your memory far more than your contemporaries are able to do.

Even during his lifetime, Beethoven was considered one of the three great composers of the era (alongside Haydn and Mozart). At his funeral on March 29, 1827, about 20,000 people attended, an unprecedented number for those times.

Beethoven Supported Napoleon and Dedicated His Third Symphony to Him

Verdict: This is only partly true.

In the 1790s, Beethoven followed Napoleon Bonaparte‘s actions with interest, but it cannot be said that he supported him. Between 1796 and 1798, Beethoven wrote patriotic songs for Viennese militiamen fighting against Napoleon, and in 1802 he dedicated three violin sonatas to Alexander I, one of Bonaparte’s main opponents.

The famous Third Symphony, which Beethoven began working on in 1803, was initially indeed dedicated to Napoleon, but this was not due to the composer’s political views. At that time, Beethoven was planning a trip to Paris; dedicating the symphony to Napoleon could have served as his entry pass to the local high society salons and attracted public attention. After Bonaparte’s coronation in 1804, the composer abandoned the idea. His student Ferdinand Ries recalled:

Both I and his other close friends often saw this symphony rewritten in score on his desk; at the top of the title page was the word ‘Buonaparte’, and at the bottom ‘Luigi van Beethoven’ – and no more… I was the first to bring him the news that Bonaparte had declared himself emperor. Beethoven flew into a rage and exclaimed: ‘So, he is just an ordinary man! Now he will trample on all human rights, follow only his ambition, he will place himself above everyone else and become a tyrant!’ Beethoven approached the table, grabbed the title page, tore it from top to bottom, and threw it on the floor.

Soon, the well-known patron and supporter of Beethoven, Prince Franz Joseph Lobkowitz, paid a generous fee for the right to perform the new work in a private circle, and then another for the dedication of the symphony to himself. The private premiere took place on June 9, 1804, in the prince’s Vienna palace. In the autumn of the same year, the symphony was performed in Roudnice, the Czech castle of Lobkowitz, especially for the Prussian Prince Louis Ferdinand, who financed this concert.

Both Lobkowitz and Louis were not sympathetic to Bonaparte, and even at the private performances, the initial dedication was not mentioned. The public premiere took place on April 7, 1805, where the composition was called the New Grand Symphony. A year later, the Third Symphony received its final title, Eroica, with the subtitle “Composed to celebrate the memory of a great man, and dedicated to His Most Serene Highness Prince Lobkowitz.” Most likely, the “great man” was Louis Ferdinand, who had recently died in battle against Napoleon.

Beethoven Was Unhappy in Love

Verdict: This is true.

A talented and famous composer, Beethoven was popular among ladies from high society. He often had romantic relationships, but they never led to marriage: Beethoven’s social status and financial situation seemed too unstable to his chosen ones and their families. Up until 1812, the composer had relationships with various women, but then everything changed.

During this time, Beethoven wrote a letter addressed to an “Immortal Beloved,” which, like the Heiligenstadt Testament, was discovered only after his death. In it, he wrote that after his final separation from this lady, he decided to give up on all romantic relationships. Beethoven never names the “Immortal Beloved,” and her identity remains unknown. It seems that he kept his promise and spent the rest of his life alone.

Beethoven Did Not Wear a Wig as a Protest Against Social Norms

Verdict: This is not true.

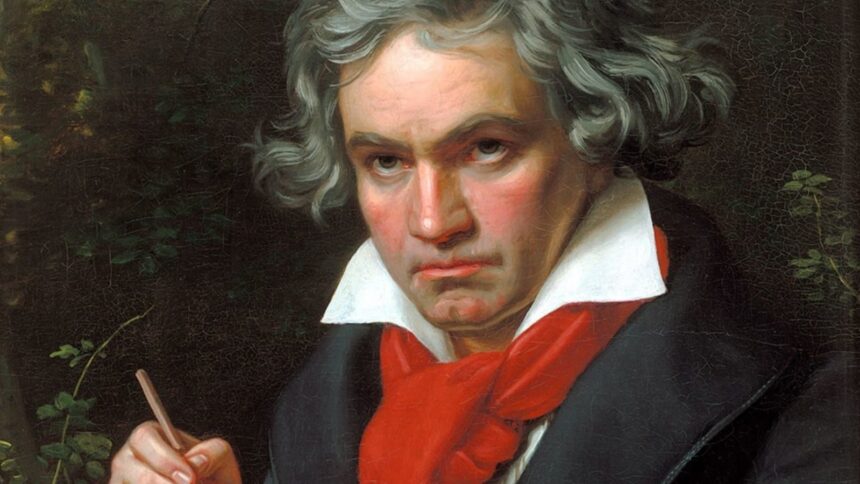

By the time Beethoven was active in social life, wigs were already out of fashion—he only wore a wig on very rare occasions. A new hairstyle from France called “à la Titus,” named after the Roman emperor, had become popular: men and women wore short hair with curls. This is precisely the hairstyle we see on Beethoven in the portrait painted by Joseph Mähler.

Beethoven’s Music Inspired Lenin’s Revolution

Verdict: This is not true.

It cannot be said that Lenin’s revolutionary ideas were influenced by his musical tastes. At the very least, there is no documentary evidence that Beethoven’s music inspired his revolution. However, from the recollections of contemporaries, we know that Lenin did enjoy listening to Beethoven. For example, Lenin’s comrade Mikhail Kedrov recalled how he played Beethoven’s music on the piano at Lenin’s request: “He could listen for hours to Beethoven’s sonatas and overtures, the genius who expressed the spirit of the French Revolution in music.”

Maxim Gorky also told a story about how Lenin listened to Beethoven’s “Appassionata” performed by Isai Dobroven in 1920. Four years later, in an article in the “Izvestia VTsIK,” Gorky quoted Lenin saying: “I know nothing better than the ‘Appassionata’; I am ready to listen to it every day. It is marvelous, inhuman music. I always think with perhaps naive pride: what miracles people can create!”

Beethoven Constantly Changed Apartments While Living in Vienna: More Than Seventy in Total

Verdict: This is partly true.

Vienna was an expensive city. Few could afford to build a mansion for themselves. Even wealthy people usually owned rental properties where they lived while renting out part of the apartments.

The typical rental term was around seven months—from late September to late April. In spring and summer, the Viennese would move to suburban areas and then return in the autumn to rent another apartment. Beethoven did this as well. During his years in Vienna (1792–1827), he indeed changed his residence frequently; we know of about thirty addresses. But it was certainly not seventy!

Beethoven Loved Beer

Verdict: This is not true.

Unlike his father, Beethoven did not like alcohol, and if he did drink, it was more likely to be wine. The composer confessed: “…alcohol brings me more of a decline than a gain in strength…”

Beethoven also loved strong coffee, which was in vogue in Vienna. It was consumed at home or in coffeehouses. While walking around Vienna, Beethoven and Haydn would stop by a café: Ludwig would buy two cups of coffee, one for himself and one for his teacher, costing 6 kreuzers each—this was relatively inexpensive at the time. Tea, however, was quite expensive and was only served in aristocratic salons.

Regarding Beethoven’s gastronomic tastes, he loved pasta with Parmesan and salami, meat (except pork), oysters, and fish—especially carp and pike.

Beethoven Suffered from Bipolar Disorder

Verdict: This is not true.

Firstly, there is no documentary evidence that Beethoven suffered from any mental illness. Secondly, such a diagnosis appeared only two centuries later.

It is known that Beethoven had a difficult personality. Outbursts of anger alternated with periods of good humor. He himself attributed his bouts of aggression and antisocial behavior to his increasing deafness. In his later years, he was constantly dissatisfied and often lashed out at his servants; he would throw books and furniture at his housekeeper.

However, these sharp mood swings did not interfere with his work, in which he was very organized and disciplined. Beethoven had a strict daily routine: he would get up early (sometimes at six in the morning), have a light breakfast, start working, and after lunch and a walk, return to composing.

Beethoven Died in Poverty

Verdict: This is not true.

Beethoven was one of the first independent composers in music history. He did not hold a salaried position but earned income from publishing his works and performing. He made quite a lot of money. Moreover, Beethoven received commissions from patrons who could also buy the rights for the first performance of a new composition in a private setting. In 1809, three Austrian patrons—Ferdinand Kinsky, Prince Lobkowitz, and Archduke Rudolph—decided to grant the genius composer a lifetime pension, which had never happened to any musician before.

Beethoven’s expenses were considerable. He spent a lot on the maintenance and education of his nephew Karl, whom he always referred to as “dear son” in his letters. In his last months, Beethoven was very ill and could no longer compose. A great deal of money went to pay for medical expenses: “However, I submit to the will of fate and pray to God only that by His Divine grace, He may shield me from poverty as long as I am forced to endure the sufferings of this life.”