Without any doubt, Peter I is the most famous Russian monarch and one of the most notable and significant figures in Russian history overall. The first emperor who transformed his country into one of the leading European powers, founder of Saint Petersburg, and author of radical cultural transformations, he became a legend both in Russia and abroad even during his lifetime. Peter’s behavior was also unusual for a monarch: his disregard for ceremonies, his manner of exuberantly entertaining himself and dressing plainly, as well as his colorful personal life. It is not surprising that the most incredible rumors and legends about him arose among his contemporaries.

Peter I Was Swapped at Birth

“The sovereign was swapped” is one of the most common themes in popular mythology about rulers. Essentially, if a divinely appointed ruler does something we strongly dislike, there could be two explanations: either such a ruler was sent to us from above as punishment for our sins, or he is “not real,” meaning he was swapped. From the materials of the Preobrazhensky Prikaz and the Secret Chancellery, we know that both of these scenarios were widely discussed by contemporaries, and the unprecedented fact of the sovereign’s incognito trip abroad only added fuel to the fire.

However, to discuss this version seriously is not warranted: Peter I was the legitimate son of his father, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, from his second wife, Tsarina Natalia Naryshkina.

Verdict: This is false.

Peter I Was of Gigantic Stature and Had a Small Head

Contemporaries unanimously noted Peter’s tall stature, but how tall he actually was is unknown. Whether the surviving mark in Peter’s Cabin, which suggests his height exceeded two meters, is a reliable source remains questionable. On the other hand, the clothing that has survived and undoubtedly belonged to him does not amaze with its size.

However, even by our standards, if Peter was a person of average height—over 170 cm—he still would have seemed very tall to his contemporaries, who were significantly shorter. As for the claim that he had an abnormally small head, there is no evidence.

Verdict: This is partly true.

Peter I Exchanged Chuvash People, Redheads, or Votyaks for Nails

The origin of this particular legend is unclear. But it is worth remembering that a significant part of Russia’s population consisted of serfs; the rest could be turned into serfs at any moment by a mere stroke of the sovereign’s pen. Selling, gifting, or exchanging a person or an entire populated estate seemed entirely normal to people of that era. This was especially true for “foreigners” and non-Christians, such as prisoners or those brought from abroad—often young Turks or Kalmyks.

Equally common was the “collection” of people by monarchs or even wealthy landlords who appeared unusual due to their appearance: “Samoeds,” “Arabs,” “giants,” “freaks,” “dwarfs,” and fools. This, however, was not only practiced in Russia: such live “curiosities” could be exchanged between monarchs. For instance, in 1717, Peter ordered “two Samoed boys, who were uglier and funnier,” to be found and sent as a gift to the Duke of Tuscany; the Duke gladly accepted the gift. However, Peter probably did not exchange people for nails.

Verdict: This is likely false.

Peter I Killed His Own Son

Peter threatened his son with death, after which the court he appointed did indeed sentence the tsarevich to execution. According to the official version, however, he died of a stroke, that is, a heart attack. Similarly, in the 18th century, the deaths of other rulers who died under suspicious circumstances were explained. Whether Tsarevich Alexei was secretly executed or died, for example, from torture to which he was subjected after the sentence, is not so important. His death in captivity in the Peter and Paul Fortress could not have occurred without the knowledge and at least tacit approval of Peter.

The sovereign was just as ruthless towards his other subjects. According to legend, during the mass execution of the rebellious Streltsy, he personally took up an axe. This legend originates from a report by a foreign diplomat, so there is no absolute certainty of its accuracy. However, it is precisely known that Peter personally attended interrogations in the dungeon for hours when those suspected of treason were tortured. The number of those tortured in dungeons, killed while suppressing revolts, or simply dead from hunger and disease on the battlefields or during the great construction projects of the era cannot be counted. What is clear, in any case, is that the era was bloody.

Verdict: This is true.

Peter I Was An Atheist or a Protestant

Of course, we cannot know for sure whether Peter (or anyone else) believed in God. Many contemporaries already considered Peter a non-believer, a Protestant, or even the Antichrist, and some of them paid for these views with their lives. Such a perception of the monarch is unsurprising, given his radical reform of the Church, his irreverent attitude toward the church hierarchy and rituals, and his personal behavior, which ran counter to church norms. However, the crude entertainments that Peter indulged in during the “All-Joking, All-Drunken Synod” would seem equally shocking to any modern atheist.

It is also true that Peter, it seems, attached less importance to the theological differences between Orthodoxy and other Christian denominations. And there is no doubt that Feofan Prokopovich, who determined Peter’s church policy starting from the mid-1710s, was under the strong influence of Pietism, the most important Protestant movement of that time. How much Peter delved into the doctrinal essence of the innovations proposed by Prokopovich is unclear, but he was clearly drawn to the model of state subordination of the Church, characteristic of many Protestant countries.

Nevertheless, it is utterly impossible to imagine that Peter I did not consider himself an Orthodox Christian, and even more so that he was an atheist in the modern sense. There is a wealth of evidence of Peter’s deep piety; while he mocked church rituals in some cases, he devoutly observed them in others. Finally, he naturally regarded God as the source of his own power.

Verdict: This is false.

Peter I Opened a Window to Europe

It is believed that this metaphor was first used by the Italian Francesco Algarotti in his notes after visiting Russia in the late 1730s, more than ten years after Peter’s death. In reality, Algarotti compared St. Petersburg to “a window through which Russia looks into Europe.” His metaphor was later picked up by Pushkin and popularized in “The Bronze Horseman” (where he, by the way, directly refers to Algarotti). In Pushkin’s poem, Peter expresses his intention to “cut a window to Europe,” and, judging by the context, the meaning of this “window” is somewhat different from Algarotti’s: it is more like an opening through which Europe flows into Russia.

Either way, the metaphor is quite accurate. Naturally, Russia was not isolated from Europe before the founding of the new capital on the Neva River.

But it was St. Petersburg that became Russia’s main trading port; many foreigners lived there; and it was through St. Petersburg that various cultural influences, novelties, fashions, new institutions, and behavior models from Europe penetrated Russia.

Verdict: This is more likely true.

Peter I Brought Potatoes to Russia and Forced Peasants to Eat Them

Peter may have indeed brought some potatoes to Russia as a curiosity — he ordered all sorts of oddities, like pickled mangoes, for instance — but no campaign to promote potatoes took place during his reign. Potatoes only started to take root in Russia much later, in the second half of the century.

Verdict: This is false.

Peter I Issued a Decree “On the Bold and Foolish Appearance” of Subordinates

During his reign, Peter personally wrote many decrees, often addressing the most insignificant matters and sounding, by our standards, strange and rather rude. For example, there was the 1707 decree requiring all members of the ministerial “conzilia” to sign meeting protocols, “for by this all foolishness will be revealed.” This meant that ministers who gave bad advice could not later deny it. Many decrees originated from the monarch’s oral orders, which explains the colloquial, even coarse, tone of some of them.

On the other hand, many of Peter’s sayings are known only through retellings by contemporaries or their descendants. By the end of the 18th century, two important publications had appeared that collected many of these sayings: “Stories of Nartov About Peter the Great” and “Deeds of Peter the Great, the Wise Reformer of Russia.” In both cases, the publishers — the son of Peter’s court turner and mechanic Andrey Nartov, and amateur historian Ivan Ivanovich Golikov, respectively — took considerable liberties with the sources.

Against this backdrop, it’s easy to attribute all sorts of sayings to Peter — including the decree for subordinates to have a “bold and foolish appearance in front of their superiors so as not to disturb them with their intelligence.” However, historians know nothing about the existence of such a decree. It’s a fake, apparently spread in the internet age. Its content contradicts everything we know about Peter: his genuine decrees, on the contrary, encourage subordinates to “disturb” their superiors and report them to the sovereign.

Verdict: This is false.

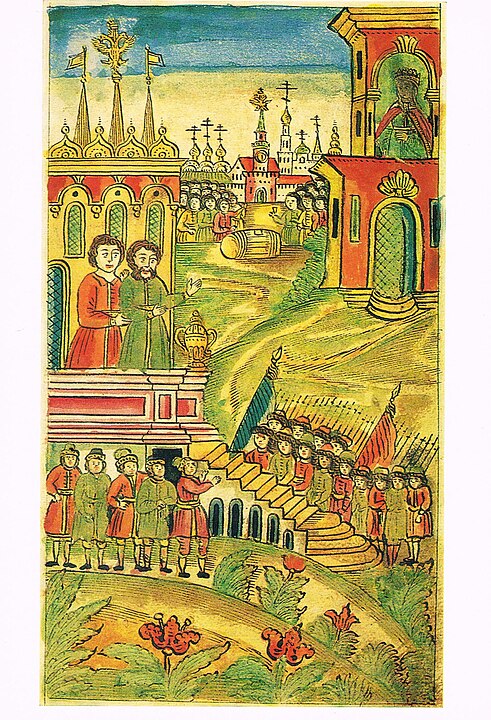

Peter I Chopped Off Beards with an Axe

Peter did indeed begin to fight against beard-wearing after his return from the Great Embassy in August 1698. There is evidence that in some cases, he personally cut off the beards of the boyars. The imperial envoy Count Guarient reported that the young tsar personally trimmed the long beards of many boyars, as well as other clergy and laypeople. There are other similar accounts, but an axe is not directly mentioned in any of them.

Most likely, the cutting of beards got mixed up with another episode involving Peter: during the infamous Streltsy executions, the tsar, according to the testimony of a foreign diplomat, wielded an axe himself. Such a mix-up is not surprising. The beard-cutting episode occurred immediately after the Streltsy uprising, in which Peter suspected many elite members of sympathizing, so beard-cutting apparently also served as a symbolic punishment through humiliation. It is possible, however, that the soldiers sent to enforce the beard-shaving decree in the provinces may indeed have used an axe.

Verdict: This is almost true.

Peter I Was an Alcoholic and Forced Others to Drink

It is impossible to say retrospectively whether Peter was an alcoholic in the strict medical sense, but descriptions by contemporaries and Peter’s own letters leave no doubt: yes, he and his entourage drank excessively, and yes, guests at Peter’s feasts were forced to drink liters of alcohol. One could argue whether there was a political intent — to loosen tongues, to elicit hidden thoughts. Moreover, it was not only at the Russian court but also at many European courts where people regularly drank themselves into a stupor.

It is also true that Peter’s customs matched the established European stereotype of “Russian drunkenness.” When preparing to become an ambassador to Russia in the late 1720s, the Anglo-Spanish aristocrat Duke de Liria was already convinced that “all matters in those lands are conducted over a bottle.” And yet, the fact remains: many of our contemporaries would have died from alcohol poisoning after just one of Peter’s parties.

Verdict: This is true.

Peter I Hated Russia and Moscow

The origin of this myth is understandable: the tsar eradicated Russian customs, was fascinated with all things foreign, and moved the capital to St. Petersburg. Does this mean he hated Russia and Moscow? Of course, there are no documents where he directly confesses his feelings.

Peter could not have hated Russia; he was deeply convinced that ruling Russia was a task entrusted to him by God, and that he would have to answer for the country’s fate on Judgment Day. Moreover, it was Peter who introduced the idea that the military and officials serve not only the sovereign personally but also the homeland. According to him, even the tsar serves.

However, Peter certainly hated many of the Russian ways. As for Moscow, it symbolized everything Peter wanted to change in Russia. Moreover, it was associated in the emperor’s mind with his childhood fears, uprisings, and conspiracies. Nevertheless, Peter acknowledged the symbolic significance of Moscow and spent quite a bit of time there even after the founding of St. Petersburg.

Verdict: This is more likely false.

Peter I Was Just, Severe, and Quick to Forgive

In popular mythology, “just, severe, and quick to forgive” are essential attributes of any strong ruler, a true tsar. How much do these attributes reflect reality in the case of Peter?

He certainly considered himself just and consistently emphasized his commitment to the law and the principle of fair reward for service. However, he often violated the very laws he had created.

He was certainly “severe”: being extremely quick-tempered, he could instantly sentence an offender to death or severe punishment. However, the opposite situation was also common: the tsar was aware for years of the crimes and theft of his close associates but did nothing. He could probably be considered quick to forgive, but this tendency was more often associated with the influence of his second wife, Catherine, who repeatedly saved guilty nobles from execution.

Verdict: In some sense, this is true.

Peter I Himself Worked on the Construction of St. Petersburg

Peter took pride in his calloused hands (literally): he enjoyed manual labor and had a deep understanding of the technological details of various crafts—from shipbuilding to metal forging—planting trees in gardens, and so on. In his spare time, he enjoyed working on a lathe, a hobby that was quite popular in Europe at the time. When in St. Petersburg, he regularly inspected construction sites and shipyards. During such visits, he could certainly grab a wheelbarrow or a shovel. However, it is unlikely he had the time or desire to shovel for an extended period.

Verdict: This is true.

Peter I Suffered from Syphilis, Epilepsy, and Mental Illness

Retrospectively diagnosing medical conditions is a thankless task. Nonetheless, rumors about Peter having a venereal disease were circulating even during his lifetime. Informed foreign diplomats reported that this very disease led to his death, which aligns well with the known circumstances of his demise: Peter died in excruciating pain caused by a urinary tract obstruction and associated bladder inflammation, which could have been caused or exacerbated by a long-standing venereal disease.

The version of epilepsy also does not contradict known descriptions of his behavior (contemporaries often mentioned convulsions, fits of rage, tics, and the like). As for mental illness, that, of course, is pure speculation. Did many of his contemporaries consider the tsar’s behavior abnormal? Certainly.

Verdict: Quite possibly, this is true.

Peter I Had a German Mistress

The relationship between Peter and Anna Mons was widely known to contemporaries and is reflected in many sources; even Anna’s letters to the tsar have been preserved. Peter broke off with his mistress after discovering she was cheating on him with a Saxon diplomat. She later even married a Prussian ambassador. However, Anna’s closest relatives continued to serve at court, and her younger brother Willem apparently even became the lover of Peter’s second wife, Catherine, which cost him his life.

Verdict: This is true.

Peter I Was the Father of Mikhail Lomonosov

Besides Anna Mons, Peter had many other love affairs: with court ladies who became his more or less permanent mistresses, with maidservants, or with random women he encountered during campaigns and travels. As with Peter’s relationship with Anna Mons, these affairs were described in reports by foreign diplomats and widely discussed among the people: we know about this from the investigative files of the Preobrazhensky Prikaz and the Secret Chancellery.

In court circles, it was whispered that Peter’s illegitimate children included the legendary military leader Peter Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky and Field Marshal Count Zakhar Chernyshev; both their mothers had at one time been the emperor’s mistresses.

However, substantiating the version that Lomonosov was among Peter’s illegitimate children is difficult. During the scholar’s lifetime, such rumors did not exist. This legend originates from the memoirs of Arkhangelsk sailor Vasily Korelsky, published in our time; in them, the author referred to family legends and a certain manuscript allegedly kept in their family before the war but then lost. These testimonies are highly dubious.

According to Korelsky, Lomonosov’s mother supposedly met Peter in early January 1711 in Ust-Tosno, but this period of Peter’s life is well-documented, and he was not in the North at that time. The assumption that Lomonosov owed his career and position at court to his status as a bastard is pure speculation and not supported by any evidence.

Verdict: Most likely, this is not true.