Kamikaze – Not Just Pilots

People usually imagine kamikaze (from the Japanese “divine wind”) as suicide pilots crashing their “disposable” planes into American ships. And in part, they are right.

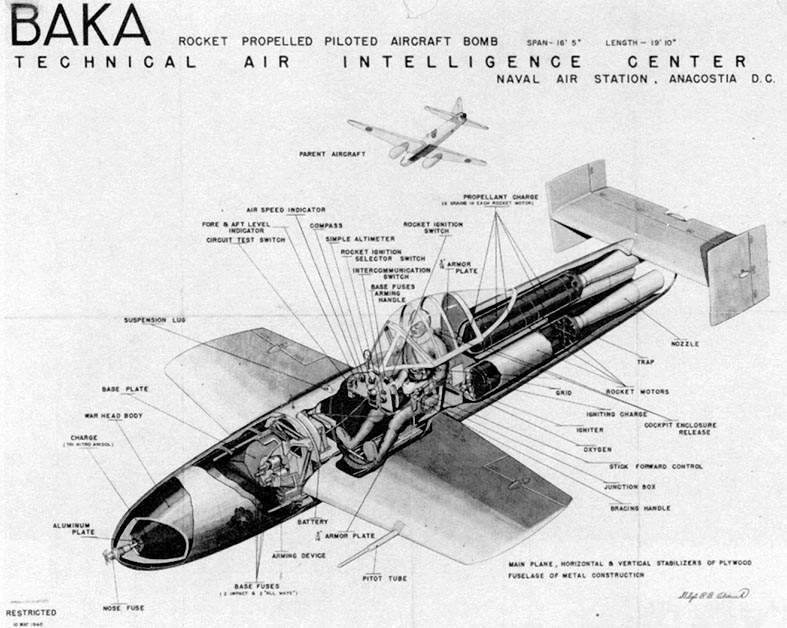

Special aircraft called Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka were designed for these daredevils—flying bombs that were not built for landing. They were delivered to enemy aircraft carriers attached to Mitsubishi G4M bombers.

But there were other types of kamikaze. For example, the Japanese developed submarine torpedoes called kaiten (from the Japanese “turning the tide of fate”). Yes, the people of Nihon love poetic names. Kaiten pilots would get into their mini-submarines, approach enemy ships, and blow themselves up.

The first modifications of kaiten allowed for ejection. However, no one survived underwater explosions anyway, so the samurai decision was made to abandon this feature.

In addition, there was a ground version of kamikaze—soldiers armed with a handheld anti-tank weapon called Ni05, which was literally a grenade on a stick. The operating principle was simple: shout “Banzai!”, run toward an American tank, hit it, and explode. If lucky, the tank blows up too.

Furthermore, kamikaze were not exclusive to Japan; the Third Reich had its own version. Specifically, the “Leonidas Squadron” of the 200th Bomber Wing in the Luftwaffe. This unit trained suicide pilots to replace the V-2 rocket, which they never had time to complete.

Around 70 people were recruited into the squadron, and from April 17 to 20, 1945, during the Battle of Berlin, these suicide bombers launched attacks on the bridges surrounding the city. However, they did not achieve significant success.

Not All Kamikaze Died

There’s a joke: two kamikaze pilots, one experienced and one new, are waiting for takeoff. The experienced one asks, “First time, huh?” And there’s a grain of truth in this joke: some kamikaze did indeed survive their missions.

There were cases where kamikaze returned to base after failing to find a target or were rescued from the sea following a failed attack.

A petty officer, Takehiko Ena, managed to survive three suicide missions. His first mission to an American aircraft carrier failed when the plane couldn’t take off. On his second attempt, Takehiko’s engine broke down mid-flight, and he made an emergency landing.

During his third flight, the engine malfunctioned again. Ena and two comrades crash-landed into the water, swam to a nearby island called Kuroshima, and stayed there for two and a half months before being rescued by a Japanese submarine. In the end, the unlucky kamikaze survived the war, reevaluated his views, and lived to be 92 years old.

Surviving kamikaze were not well-received by society. You set out to perform a noble act of self-sacrifice but then changed your mind—how could that be acceptable?

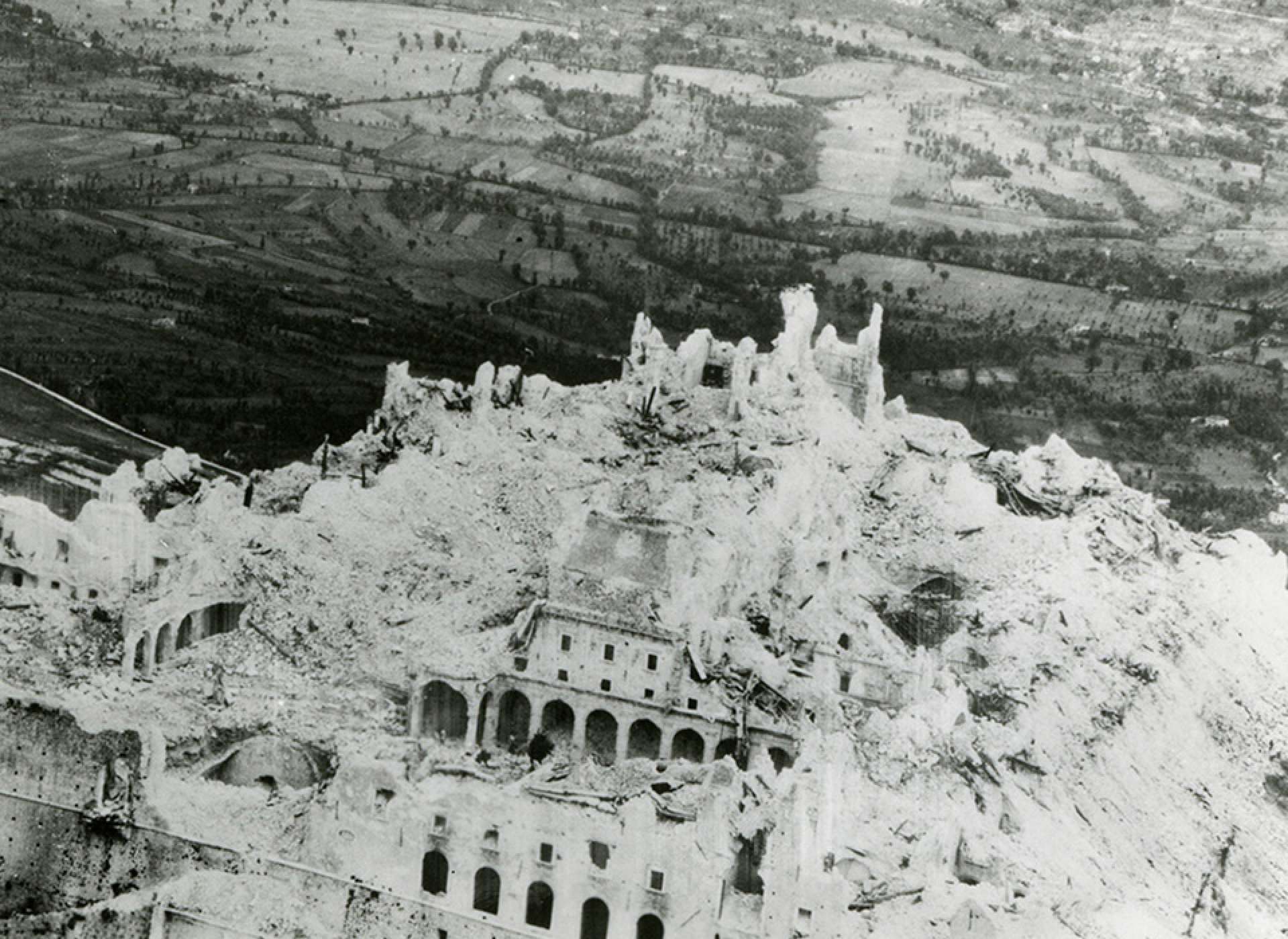

Kamikaze Were Not Very Effective

The Japanese believed that attacks at the cost of one’s own life should be incredibly destructive. Additionally, they expected that kamikaze would have a profound psychological effect on American troops: the samurai were supposed to create an impression of Japanese invincibility. But these hopes were not fulfilled.

American sailors scornfully referred to kamikaze as “baka bombs.” “Baka” in Japanese means idiot.

During World War II, a total of 1,321 kamikaze gave their lives, resulting in the sinking of 34 American and British ships. However, this did not prevent the Allies from capturing the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

Kamikaze Recruitment Was Voluntarily Compulsory

Kamikaze are usually seen as enthusiastic individuals who eagerly volunteered to sacrifice their lives for the emperor. But in reality, not all of them were so eager to sign up for a suicide mission.

When Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi of the Japanese Navy came up with the idea to create a squadron of suicide pilots, the high command approved it on one condition: only volunteers could be recruited. Takijiro readily agreed.

To stir up patriotic feelings among young pilots, the experienced samurai commanders employed certain psychological tactics.

They handed out questionnaires to candidates with the question: “Do you want to become a kamikaze?” with three response options: “I passionately wish to join,” ”I wish to join,” and “I don’t wish to join.” However, the pilot was required to write down their name and rank on the form, and if anyone had the audacity to answer negatively, both they and their families could face retaliation from the command.

Moreover, since the testing was conducted in groups, the likelihood of refusal was further reduced—it’s hardest to be seen as a coward in front of your comrades. In fact, those who agreed but without much enthusiasm were brutally beaten with clubs to “instill a fighting spirit.”

As soldier Irokawa Daikichi wrote, “Struck on the face so hard and frequently that [his] face was no longer recognizable.” As you can imagine, this hardly aligns with “voluntary self-sacrifice.”

Kamikaze Departed on Their Mission with Grace

Despite the coercive methods mentioned, being a kamikaze was considered extremely honorable among young Japanese soldiers. They strived to leave for their first and final mission with dignity.

For example, in the winged bombs, that is, the Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka planes, there was a designated place behind the pilot’s head for securing a samurai sword. Additionally, kamikaze would write farewell haiku poems—similar to samurai preparing to perform seppuku.