Economist Jean Fourastié used the phrase “Trente Glorieuses” (the Glorious Thirty) to describe the prosperous years after the Liberation and continuing into the 1970s. France was in shambles by the time World War II ended. Cities had to be rebuilt and, as part of the Marshall Plan, the United States provided financial aid to help kickstart the country’s flagging economy. And these changes included heavy governmental intervention in the productive sector. This period was a veritable economic miracle for France. The period saw both a rise in GDP and a general improvement in living conditions in France.

The period from the Liberation to the 1970s was a period of prosperity referred to as the “Trente Glorieuses” by the economist Jean Fourastié. At the end of World War II, France was devastated, with many cities completely destroyed and in need of reconstruction. To revive the struggling economy, significant reforms were undertaken with massive state intervention in the productive sector, funded by American assistance through the Marshall Plan. This era is often referred to as an economic miracle, during which France experienced significant growth and an improvement in the standard of living.

France On Its Way to The Trente Glorieuses

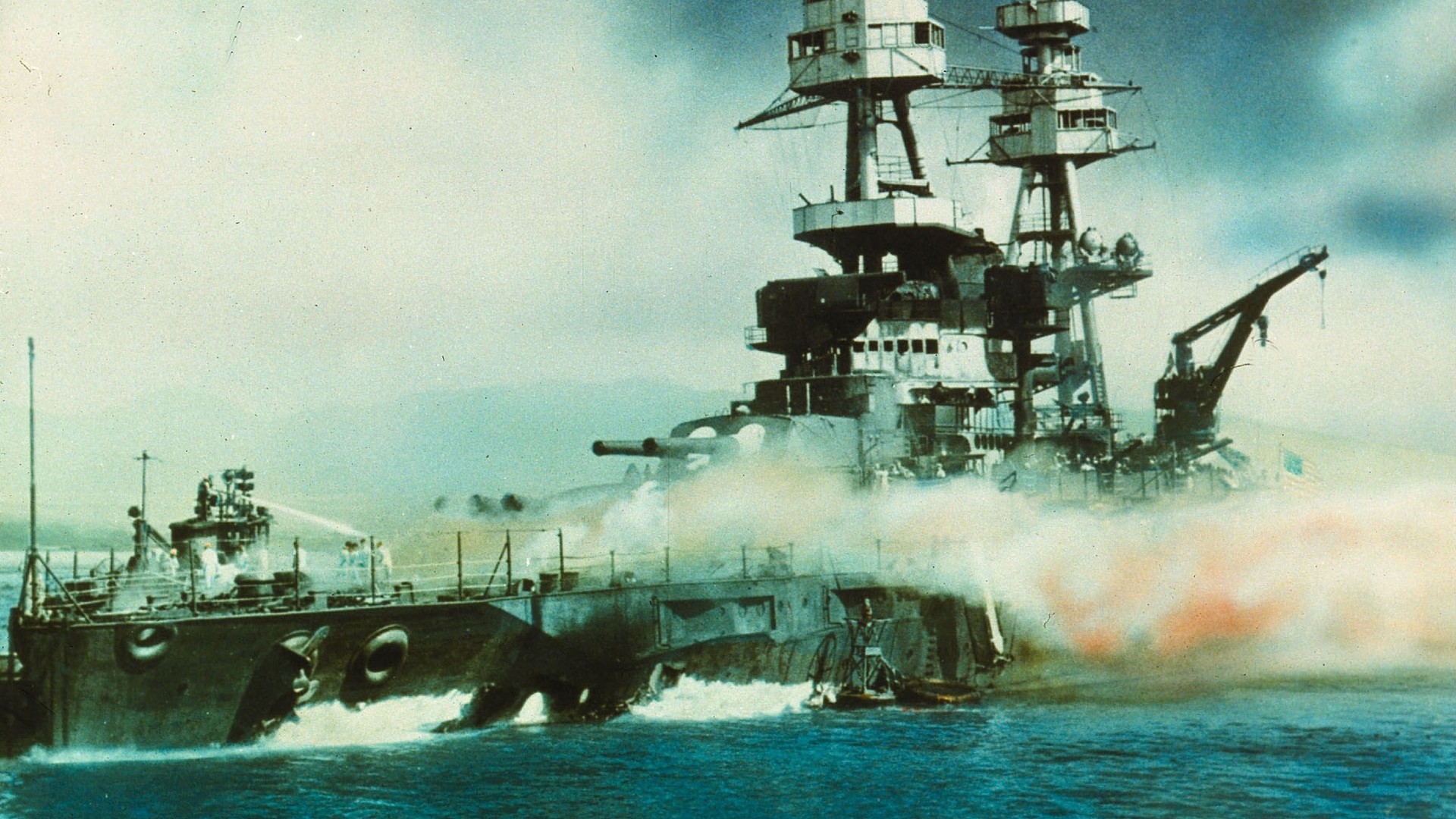

After World War II, France emerged from the conflict in dire straits, with nearly 600,000 casualties. The country had suffered significant destruction, including a severely damaged railway network and a devastated economy. Due to a lack of financial reserves, France was in a weakened state.

Upon Liberation, the economic situation was disastrous, with entire cities in ruins, a significantly reduced railway network, destroyed bridges, and cut telephone lines. This catastrophe also affected the French production apparatus. For instance, coal production fell from 67 to 40 million tons. France had regressed by fifty years. This situation, understandably, led to a thriving black market and inflation.

To address this problem, one of the first major decisions after Liberation was to increase wages. The entire French population was encouraged to participate in the production effort. This was referred to as the “third battle of France,” where terms like “reconstruction soldiers” and “rolling up one’s sleeves” were used. The economic approach during the Liberation and the Fourth Republic was characterized by a certain level of economic dirigisme, or government control and planning.

In response to persistent inflation, the government couldn’t help but intervene to rebuild and reform the country. The U.S. Marshall Plan was instrumental in providing financial support for the reconstruction of Europe. This plan distributed nearly 13 billion dollars to 13 European countries. Despite being a victim of World War II, the USSR turned down American aid, which hinted at the coming Cold War.

Reforms Leading to Progress

At the end of the war, as part of the profound economic reform, two fundamental innovations benefiting the French population were introduced. The first was the creation of the Social Security system. While it built on existing foundations, this measure went beyond mere technical reorganization.

It aimed to establish real safeguards against risks and create a fairer society. Pierre Laroque initiated this reform, which addressed the principles of solidarity and human dignity. Workers were hence protected from work-related risks such as illness, unemployment, old age, and workplace accidents, in addition to family allowances. Furthermore, the February 22, 1945, ordinance allowed the creation of committees in companies with more than fifty employees to involve workers closely in the company’s affairs.

Both of these reforms aimed to strengthen social cohesion as the country needed to rebuild its economy. However, this economic overhaul required a different level of state intervention.

What Tools Were Needed for This Transformation?

It quickly became evident that to jumpstart and rebuild the economy, several reforms and tools needed to be put in place. Thus, organizations responsible for monitoring economic developments were established. In 1945 and 1946, the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) and the General Planning Commission (Commissariat général au Plan) were founded, initially to address shortages and later to reconstruct and modernize France.

Simultaneously, a wave of nationalizations provided the government with new means of intervention. One well-known example of nationalization was the Renault factory. This measure was taken due to Louis Renault’s collaboration with the Third Reich. After Liberation, the factories were placed under sequestration, and the state, after seizing all assets, dissolved the old company and created a National Renault Factories Agency under the authority of the Minister of Industrial Production.

The state also nationalized energy production. Coal mines in France, EDF (Électricité de France), and GDF (Gaz de France) were established, and a significant portion of the banking system came under political control (Crédit Lyonnais, Société Générale).

Through this Fourth Republic, the economy was rejuvenated through state interventionism, laying the foundation for what Jean Fourastié would later call “the Trente Glorieuses.”

A Period of Economic Prosperity

France lost a lot of money due to the Great Depression of the early 20th century and the two world wars (World War I, World War II and Vichy France) that followed it. France had an extended period of exceptional development from 1945 until the 1970s.

Prosperity is measured by gross national product (GNP), but global GNP per capita went from around $2,110 in 1950 to around $4,090 in 1970 (the Maddison Method). During these “Trente Glorieuses,” the country saw rapid industrialization. The consumer goods and transportation industries reaped the most benefits. In contrast, growth was more sluggish in the core sectors of iron and steel, textiles, and basic chemicals. Increased energy mobilization was a byproduct of this expansion. As a result of its low price and high energy content, oil was quickly becoming the world’s primary growth fuel.

Another element of this economic vigor was the profound shift in the distribution of employment across the three sectors of activity. The primary sector required fewer workers, while the secondary sector experienced an increase in employment, albeit with limited benefits from the growth. In contrast, there was a significant expansion of the tertiary sector and “white-collar” jobs.

Towards a Consumer Society

The Trente Glorieuses marked France’s transition into a consumer society, mirroring the American way of life. Starting in the 1950s, the French population began acquiring consumer goods such as televisions, refrigerators, washing machines, and automobiles. Access to these consumer goods became increasingly convenient, especially through the emergence of supermarkets.

Consumption in the 1950s and 1960s was not just about meeting individual needs but also about asserting one’s social status. During this period of prosperity, daily life underwent profound changes. Families were transformed with the advent of household appliances. “Moulinex liberates women,” as the refrigerator made women “happy and fulfilled.” This family transformation allowed for more time dedicated to child-rearing, leisure activities, and, for women, the possibility of entering the workforce.

Households entered the modern world, resulting in changes in family budgets. More money was allocated to equipment, healthcare, and leisure.

The Reason for The Growth

One of the primary reasons for this economic growth lies in the supply-demand equation. During these thirty years, there was an increase in demand and, consequently, an increase in supply. This evolution was also the result of production methods such as Taylorism, Fordism, and assembly line work, where skilled workers gradually gave way to specialized labor, saving time and money. These elements allowed for increased production at lower costs. Additionally, another explanation for this growth likely lies in the extended duration of education. For instance, in 1970, there were four times as many high school graduates as in 1946.

Economic growth occurred because there was an increase in demand. Consumption increased because there were more consumers. Moreover, purchasing power continued to rise. For example, in 1948, it took more than 2,600 hours of work to buy a Citroën 2CV, while in 1974, only 1,000 hours were needed.

Finally, it’s worth noting that this period was characterized by full employment, and a significant salary reform occurred: workers began receiving monthly salaries instead of weekly pay, allowing them to allocate more substantial sums for consumption.

Economic Prosperity That Didn’t Benefit Everyone

During this period, the term “third world,” referring to countries not benefiting from this growth, emerged. However, even within the driving countries of the Trente Glorieuses, there were movements of rejection. Precarity persisted in France, stemming from poorly-paid jobs. As a result, there were individuals left behind by the growth, and shantytowns existed until the early 1970s. A “fourth world” emerged during this era of prosperity.

Some individuals also questioned this growth. They objected to the idea of an economy-controlled way of life and rejected the “work, commute, sleep” routine. Left-wing movements emerged, offering an alternative to the consumer-oriented world. They proposed renouncing the modern world and returning to rural life, as seen on the Larzac plateau, for example.

The End of the Trente Glorieuses (Glorious Thirty)

The notion that growth came to an abrupt halt solely due to the first oil shock is unfounded. Signs of an economic downturn were present in the early 1970s, and the energy crises of 1975 and 1979 only exacerbated the situation.

However, compared to the economic and social climate of the late 1990s, the Trente Glorieuses era, with its somewhat mythical name, continues to be the time when our nation experienced the strongest growth. In thirty years, it outperformed the growth France had seen between 1830 and 1914.

References

- Jean Fourastié : “The Thirty Glorious or the invisible Revolution from 1946 to 1975”, 1979 and “The great Hope of xxe siècle”, 1949

- Dominique Lejeune, La France des Trente Glorieuses, 1945-1974, Armand Colin, 2015, collection « Cursus », 192 p.

- Denis Woronoff, Histoire de l’industrie en France, 1994.

- Jean-Pierre Rioux, France of the Fourth Republic, Le Seuil, Tome 1, p. 120.