Faun (fawnu; favorable, also Fatuus, “destiny” or “prophet”) is a name exclusive to the religion of Ancient Rome (polytheistic). Originally, it defined a mythical king of the Lazio region who was transformed into a god, later undergoing various modifications due to syncretism with beings from Greek or Roman religion, causing great confusion among various myths, sometimes so intertwined with the original myth that many do not distinguish differences (for example, between the creatures called fauns in Rome and the Greek satyrs).

Initially, the name was used to designate three distinct figures: Faunus, a mythical king of Lazio deified by the Romans—often confused with Pan, Sylvanus, and Lupercus (as a god, he was immortal); Fauns (in plural, though it can be used in singular when individualizing the being)—creatures, akin to Greek satyrs, with a body that is part human, part goat, descended from King Faunus (demigods and therefore mortal); or Faun, a sailor who, having fallen in love with Sappho, obtained beauty and seduction from Aphrodite to conquer the poetess.

A king, a god

The primitive image of Faun in Roman mythology relates to the third king of Italy (Lazio), whom Virgil, in the Aeneid, mentioned receiving the Trojan Evander when he settled on the Palatine Hill. Faun would be the son of Picus, who was, in turn, the son of Saturn. He thus carried divine status through his ancestral lineage. Hacquard suggests that Faun might be the son of Jupiter and Circe, while Murray points to versions claiming he is the son of Mars.

According to Murray, Faunus or Faun was a king who, due to his beneficial actions for his people—civilizing them and introducing agriculture—was elevated to divinity after his death. He was worshipped as the representative of the woods and fields under the name Fatuus (Latin: Fatuus; lit. “Destiny, Fatality”). Hacquard, on the other hand, attributes the deification of the king to his creation of laws and the invention of the flute. According to this author, Lupercus was his other name, being an agricultural god ensuring cattle fertility and protection, especially against wolves. He enjoyed staying near springs and wandering through mountains and forests.

Descendants

Faun would be the father of Latinus, who succeeded him on the Italian throne. In old age and without a male heir, Latinus was warned in a dream by Faun that his granddaughter Lavinia should marry a foreigner—not one of the many neighboring suitors courting her. The foreigner turned out to be the hero Aeneas. Hacquard confirms this version but questions whether Latinus might be the son of Hercules instead of Faun. From the union of Aeneas and Lavinia, Faun prophesied in the dream that a race would arise that would dominate the world: the Romans. This version is confirmed by Nennius, who narrates Aeneas’s journey to Lazio, where he defeats Turnus, one of Lavinia’s suitors.

Some versions of the myth present Fauna as the daughter of the king, who, inebriating her and assuming the form of a serpent, violated her.

In the myth of Acis and Galatea, Galatea declares that Faun is the son of Faun and a nymph.

Representation

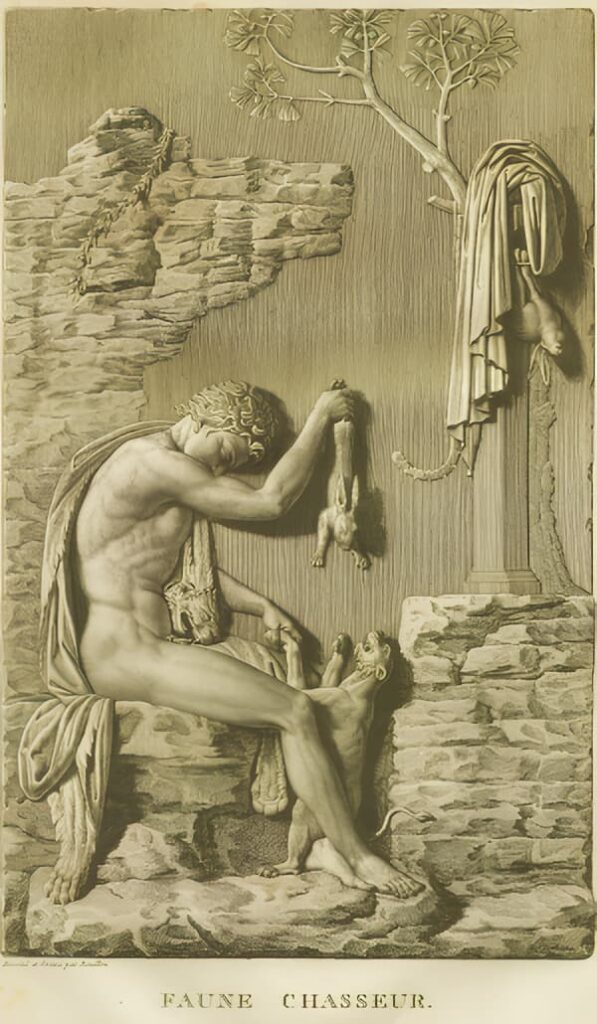

The depiction of Faun in ancient paintings and sculptures portrays him as a bearded man with a crown of leaves on his head, wearing only a goat’s skin and holding a cornucopia. Ovid tells us that he had horns on his head, and his crown was made of pine.

As for the fauns, Dillaway mentions, “The Romans called them Fauni and Ficarii. The name Ficarii does not derive from the Latin ficus, meaning fig, as some imagined, but from ficus, fici, a kind of tumor or excrescence that grows on the eyelids and other parts of the body, which the fauns were depicted as possessing.”

Synchronistic Trends

Faun and Fauna

Fauna, besides the version that considers her as Faun’s daughter, would have been in other versions his wife, from whose union the fauns originated. According to some sources, she would have become intoxicated with wine and then beaten to death by her husband, despite her moderate habits. She would also be a sister of Faun.

Fauna, in turn, was also associated, by the Romans, with the Good Goddess. Like Faun, she also possessed oracular gifts, though in her case, directed only towards women.

Faun and Pan

Being an ancient deity of Italy, during Roman times, Faun acquired characteristics that made him similar to the Greek god Pan. However, the Romans did not directly assimilate Pan to Faun: at times, their characteristics are combined, while at other times, Faun is related to the god Silvanus.

According to Menard, the spread of Greek myths in Italy led to the confusion of relationships between Pan and Faun, even though their legends were distinct.

Faun and Silvanus

For Bulfinch, Silvanus and Faun were Roman gods so similar to Pan that he considers them the same character with different names. The subtle difference, if any, is indicated by Dillaway, stating that “the fauns were a kind of semi-gods, who, when inhabiting the forests, were also called Silvans.

“

Faun and/or Lupercus

As the protector of cattle, Faun is given the name Lupercus (or Lupercius: “the one who repels wolves”). These names were those with which Pan was identified in Rome. The association of the names – Faun Lupercus – seems common.

Cult

According to Bailey, myths like that of Faun, associated with field or wild beings, have a less dignified character than those devoted to the Lares gods. The Romans attributed a wild and mischievous nature to Faun, as well as to his companion Inuus (one of the di indigetes), reflecting an animistic belief in the natural malevolence and hostility of these spirits.

The worship of Faun took place in sanctuaries, the main one being the Lupercal, located on the Palatine Hill, in the cave of Romulus and Remus. Its priests were called Luperci, who used whips made from goat leather. Their purpose was to cater to those seeking fertility. Menard emphasizes that this fertility aspect in herds was a common trait of all primitive Italic gods, hence Faun received honors from shepherds.

Faun was especially worshipped for his oracular gifts. His predictions occurred in the woods and were communicated to those who desired them through dreams. For this, the consulter had to sleep in the sacred places of the god, on animal skins specifically sacrificed to him.

The Cave of Faun

The mythological cave where the She-wolf of Mars allegedly nourished the twins Romulus and Remus, called Lupercal, had the same name as the place of worship for Faun (in its devotional variant of Faun Lupercus). For Hacquard, for example, it was merely a coincidence of names.

In 2007, however, the Italian Minister of Culture, Francesco Rutelli, announced the discovery of this sanctuary in Rome. It features decorations on its walls, a vaulted ceiling, and dimensions of 6.5 meters in height and 7 meters in diameter. The cave, now a real place and not a fantasy, has been dated to the Bronze Age.

Prophecies

In the cave, according to the story, the Romans obtained the prophecies of Faun. Gibbon narrates Carus’s rise to power in Rome without the Senate’s approval. An eclogue, then composed, flattered the new emperor: two shepherds, avoiding the midday heat, rest in Faun’s cave. Under a leafy beech tree, they discover recent writings; the rural deity described, in prophetic verses, the happiness of the empire under the reign of such a great prince. Faun greeted the arrival of that hero who, bearing the weight of the Roman world on his shoulders, would extinguish wars and factions, restoring once again the innocence and security of the golden age.

Hacquard also recalls the episode where Numa Pompilius—one of Rome’s mythical kings—had to chain his effigy to obtain its oracle services.

Lupercalia and Faunalia

The festivals dedicated to Faun (Lupercus) took place on February 15, which was considered the date of the foundation of his temple, Lupercal. This festival was essentially rural, as Faun Lupercus had the primary function of protecting herds (“Lupercius” thus being “the one who repels wolves”). They were a form of purification, aiming to achieve great productivity in agriculture and livestock breeding. Initiated by Evander, the festival persisted until the 5th century when the Church incorporated it, transforming it, according to Georges Hacquard, into the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin.

Bailey emphasizes that the notoriety of this festival reached the present day thanks to the political use made of it by Mark Antony in 44 B.C.

On December 5, another festival occurred, Faunalia, similar to Lupercalia. In these, the priests of Faun, called Luperci, walked the streets, administering lashes to people with whips made of goat skin.

The Fauns

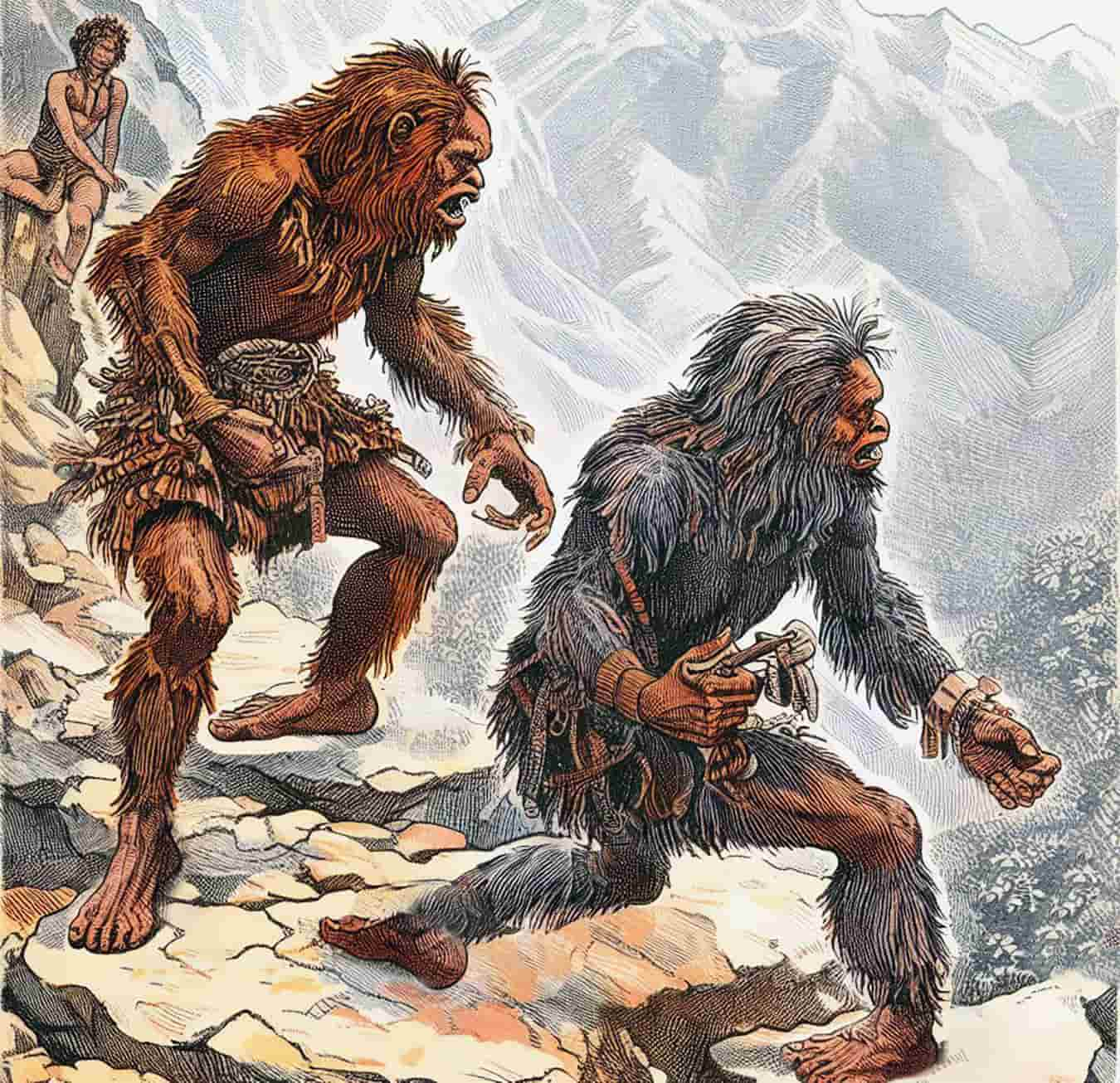

Deities of the countryside were said to have a fairly long life, although they were not immortal—similar to the Silvans of Rome and the Greek satyrs.

They also differ little from the fauns and the satyrs, being small deities playing a role analogous to that of mythical heroes, acting as intermediaries between gods and men, according to Menard. Therefore, they serve as intermediaries between purely instinctive animals—in this case, the goat—and the deities. According to this author, their creation is solely attributed to sculpture, as philosophers have no references to them.

Dillaway defines fauns, as well as satyrs, in this way: “They were the children of Faun and Fauna or Fatua, king and queen of the Latins, and although considered demigods, it was likely that they died after a long life. Indeed, Arnobius showed that their father or chief lived only a hundred and twenty years. The fauns were Roman deities, unknown to the Greeks. The Roman Faun was the same as the Greek Pan; and, as in the poets, we find frequent mentions of fauns, Pans, or Panes in the plural, it is more likely that the fauns were the same as the pans, and all descended from a single progenitor.”

Animal Nature of the Fauns

Menard brings an important quote in his studies on artworks depicting fauns and satyrs, reporting on the distinct nature of satyrs and fauns, despite himself confusing the two in the descriptions he provides, treating them as synonyms. He reproduces the following passage from the critic Clarac, who says:

“(..) I called this statue Faun, along with the writers who preceded me, but its true name must be Satyr. There is no doubt that Faun is only a deity from Roman mythology, and the beautiful marble is undoubtedly either a Greek statue or a copy of a Greek statue. It is known that satyrs, in ancient mythology, had human forms except for the ears and tail of a horse. Fauns resembled them, but after Zeuxis, they started to have a goat’s tail.”

Influence and Artistic Representations

Fine Arts

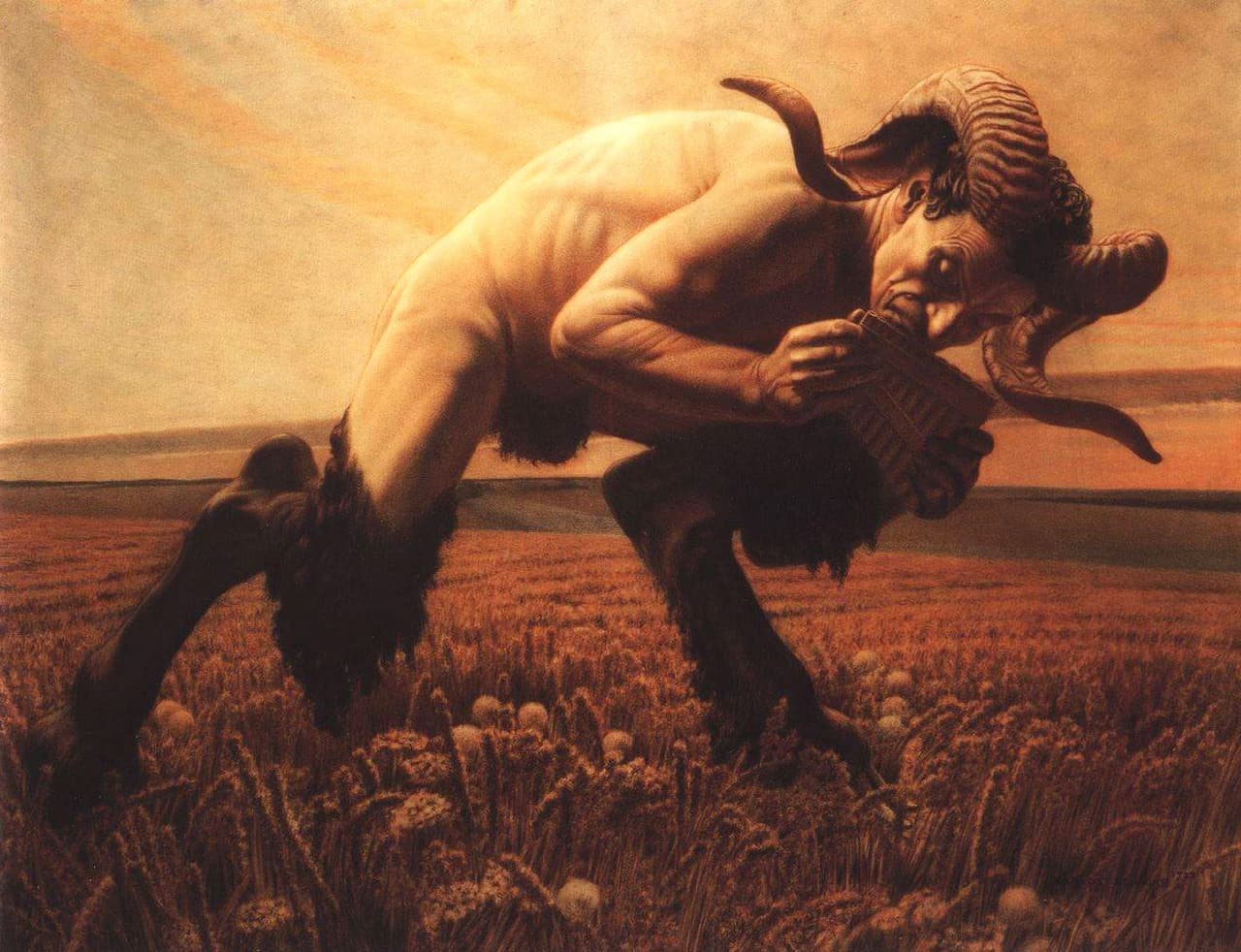

The fusion of the fauns’ image with satyrs has produced, in recent centuries, representations of these beings in scenes depicted by artists.

From ancient times to the present day, there are various representations of Faun or fauns by different artists.

Below is a small gallery with some of their most expressive representations.

Classical Literature

Horace dedicated one of his odes to Faun, although in three others, he refers to the Roman god or his descendants.

In the ode to Sextius (Ode IV), he says:

“Now he is also preparing to sacrifice to Faun, in the shady groves, whether he demands a lamb, or if he will be more pleased with a child.”

In the song to Tyndaris, another invocation to the protector god of fields (Ode XVII):

“The clever Faun often moves from Mount Lycaean to pleasant Lucretilis and always defends my goats from the scorching summer and the rainy winds.”

In the ode to Maecenas, Horace narrates how he was saved from death by Faun (Ode XVIII):

“And a tree trunk falling on my skull would have dispatched me if Faun, the protector of men of genius, had not repelled the blow with his right hand. Be diligent in paying the victims and vows of the temple; I will sacrifice a humble lamb.”

And finally, Ode XVIII is dedicated to Faun, as “A Hymn.”

“Oh, Faun, you lover of flying nymphs, kindly cross my fences and sunny fields, and be favorable to the young offspring of my flocks; if a tender child falls (a victim) for you at the end of the year, and they do not want enough wine in the cup, the companion of Venus, and the ancient altar will exhale smoke with its generous fragrance. All the cattle frolic on the level ground when the ides of December return to you; the village that observes the holiday enjoys leisure in the fields, along with the oxen also free from labor. The wolf wanders among the sheep without fear; the trees open the doors of the forests for you, and the laborer rejoices for having conquered the abominable soil in a triple dance.”

Ovid portrayed Faun with horns and crowned with pine leaves, and Virgil emphasized his oracular gifts, perhaps due to the etymology of his name in Greek – φωνειν, from the Latin Fari, which would be a supposed derivative, meaning “to speak.”

Modern Literature

Several works evoke the figure of the faun in literature, sometimes in its image as a satyr, sometimes pointing to the Roman version (rather than the purely Greek one) of the myth. Some examples:

John Milton evoked fauns when describing Eve’s dwelling:

“In more shaded and protected shelter

Pan or Sylvanus have not slept, and nymphs

And fauns have not visited another like it.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne published in 1860, “The Marble Faun,” a novel set in Italy, where he had lived for some time. The plot blends travelogue, fable, and gothic elements.

The poem “L’Après-midi d’un Faune” by Stéphane Mallarmé, published in 1876, was a milestone in French literature, as a symbolist masterpiece. In the work, the author depicts a faun recalling the sensual adventures he had in the morning with nymphs.

“Which to the exaltation of your senses do you attribute?

Faun, the illusion escapes from the blue and cold eyes

Like a source in tears, of the purest

All sighs, do you think it contrasts with another

Like warm morning breeze on your fleece?

But no! in the weary spasm and suffocation

Of the heat that morning fights, it murmurs

Water if not poured by my pure flute.”

In 1907, João Grave, a Portuguese author, wrote “O Último Fauno,” a novella.

The sonnet “De um Fauno” by the Brazilian symbolist Emiliano Perneta highlights the sensuality of the character.

“The lady flees, does not want me to advance…

My desire, however, is a stag. At a glance,

Seeing her, he runs to want to suck her clear honey…”

Perneta, along with other authors who marked the beginning of the symbolist movement in Brazil, such as Cruz e Sousa and Oscar Rosas, formed part of a group centered around the newspaper Folha Popular in Rio de Janeiro and took the figure of a faun as their emblem.

In C. S. Lewis’s “The Chronicles of Narnia,” the second book, “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,” features the faun Mr. Tumnus. Another faun named Urnus is identified in the sixth book, “The Silver Chair,” serving the dwarf Trumpkin, made regent of the kingdom of Narnia.

Ballet and Classical Music

Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem inspired Debussy to compose his “Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune,” which premiered in 1894. In it, the faun presents his flute, and the composer inaugurates modern music.

Premiered on May 29, 1912, at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, Debussy’s music was choreographed by the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, maintaining the same original title, “L’après-midi d’un faune.”

The presentation of Nijinsky’s version was so impressive that, in a letter, the painter Odilon Redon, a friend of the poet Mallarmé, expressed:

“Often, great joy is accompanied by great pain; to the pleasure that was offered to me yesterday, I add the regret of not having seen my illustrious friend Stéphane Mallarmé with us yesterday. Better than anyone, he would have appreciated the admirable evocation of his spirit. I do not believe that in the field of unreal art, one can give one of the characteristics of his art with more refinement.”

Film

The Portuguese film “O Fauno das Montanhas” by Manuel Luís Vieira was released in 1926. The film, which features a girl who feels pursued by a faun while accompanying her father on a naturalistic expedition to the Island of Madeira, premiered on May 11, 1927.

In the cinematic adaptation of C. S. Lewis’s first work, “The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,” the faun Mr.

Tumnus is portrayed by Scottish actor James McAvoy.

Guillermo del Toro’s 2006 film “El laberinto del fauno” features the faun in the title, and the creature presented has somewhat different forms from the one idealized in Roman mythology: it is part goat, part human, and part tree. The faun appears to a girl, revealing things that allow her to escape the harsh reality of the Spanish Revolution.