Instinctive fear keeps us alive; without it, our species likely would have perished a long time ago. However, fear may sometimes take on a life of its own and make us physically unwell. Because once panic takes over our minds, there’s no stopping the terrible cycle: when we fear fear, we feel even more fear. But what exactly is fear? How did it get here, and what harm does it cause? This emotion originates in a very small region of the brain, yet it has an enormous influence on human behavior.

Fear and panic take control of our minds, bodies, and lives when the normal communication between the brain’s various regions and its neurotransmitters breaks down. However, once an anxiety condition has been identified, effective treatment options are available for people suffering from it.

The mutable nature of fear

We’ve all experienced it, whether it’s the dread of walking through a shadowy alley on our own, the fright of hearing a rattling sound on the balcony late at night, or the fear we felt as kids when we dared not stand in front of the bed, convinced that a hand would snap down suddenly and grab our bare ankles. Fear is often nothing more than an irrational thought that stays with us until it’s rationalized away. However, despite the fact that our irrational apprehensions seldom have any bearing on reality, they continue to linger in our thoughts anyway.

A healthy dose of fear saves lives

And that’s a good thing, since fear serves a useful purpose. To put it simply, it is one of the finest defense mechanisms our bodies have, and without it, the human race likely would have perished a long time ago. Within seconds of being startled, we are on high alert. The human organism is geared up and ready to function at its peak when it enters the “fight or flight” state. Instantaneously, the subconscious mind takes control of the body, and it is only after a little pause that the conscious mind intervenes to assess the situation. When things get rough, though, we turn tail and flee for our lives.

The human brain is crucial to this process. Primitive instincts are kept there, and they help us respond to certain perilous circumstances in the same way that our ancestors did thousands of years ago. Contrarily, it has a high capacity for learning; this is necessary for it to create new anxieties in response to the evolving threats of each new era. This means that our brain is able to identify and evaluate potential threats in both familiar and novel contexts without prior direct experience with them. The suffocating emotion then frequently leads us to automatically give these situations a wide berth.

But fear can be illogical

Fear may take various forms and is usually hard to escape. It might be logical or illogical, and it often manifests when confronted with situations involving spiders, snakes, tests, heights, or small places. There are three basic kinds of fear: The kind of existential panic that comes from seeing an imminent fear of one’s physical or mental well-being. We worry more about being embarrassed in social anxiety than in performance anxiety. Anxiety is an irrational and meaningless emotional state, but fear describes a real and present threat.

Between healthy anxiety and anxiety disorder

All these fears have a comparable symptom set, although one with varying intensities and specifics. This occurs when several brain regions become active and then tell the body to take action. Most of the symptoms, including a rapid heartbeat, a suffocating sensation, sweaty hands, and stiffness, are well known.

However, anxiety may develop into panic attacks, which bring on physical symptoms such as chest tightness, shortness of breath, nausea, and dizziness. Anxiety disorders are diagnosed when what was once a normal emotion becomes a reoccurring panic that has lost all connection to the actual risk. There’s a fear that this may escalate to the point where the anticipation of another panic attack triggers it. Pathological anxiety is the term used by professionals to describe a condition in which a person’s normal activities are so impaired that they may benefit from treatment.

Where fear arises: Amygdala

Anxiety may have several physical manifestations, including but not limited to a rapid heartbeat, profuse perspiration, and elevated blood pressure. Like elevated blood pressure or enlarged bronchial tubes, many of these effects are so subtle that we scarcely even recognize they’re happening. This is due to the fact that the body’s response to acute danger is predicated not only on the fact that our conscious mind recognizes the circumstance as threatening, but also, and perhaps more importantly, on the fact that our unconscious mind can respond with lightning speed.

Only two nerve tracts and a small area

Here we see the autonomic nervous system at work, which controls our body’s internal processes independently of our awareness. That way, our bodies can adjust to the ever-shifting environments outside. When faced with an immediate threat, the body’s sympathetic nervous system activates to help bring all available resources to bear. The parasympathetic nervous system is in charge of recharging our bodies during rest and sleep, while the sympathetic nervous system is in charge of getting us pumped up for action.

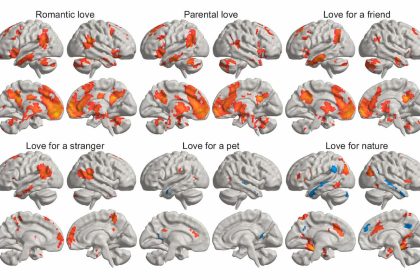

The amygdala is the region of the brain that processes emotions associated with fear, and this has been recognized for some time. Limes are part of the brain’s limbic system, which is characterized more by its function than its physical location. This encompasses a wide range of activities, such as dealing with one’s feelings.

The woman without fear

This little functional unit in our brains, the origin of our fear, is starting to paint a fairly ominous picture. Imagine a world free of fear and trepidation. This is the case when the amygdala has been damaged, preventing the maturation of a fear response. Another example of this is a very unusual clinical scenario in which the patient, dubbed “S.M.” by the medical staff, shows very little fear. Her amygdala has calcifications on both sides, impairing its ability to operate normally. ös

The scientists did not subject her to any of the following: spiders, snakes, a dungeon of horrors, or a marathon of psychological thrillers. Not a single iota of fear crept in. The researchers are rather amazed that the test subject S.M. is still alive, despite the fact that it is very “cool” not to sense fear in the scenarios indicated. Usually, fear serves as an alarm system, ensuring our safety as we go about our everyday lives.

What fear does to us

But how does the body function, exactly? Let’s role-play a potentially perilous scenario. On your trip, you see a snake in the middle of the road. The brain receives and stores a signal, including a picture of the snake. There, it first reaches the thalamus, the brain’s sensory control hub. That’s where all the information from our senses goes on its way to our brain. The thalamus then relays the information in two ways: swiftly to the amygdala and considerably more slowly to the cerebral cortex.

The subconscious mind thinks for us

When the amygdala receives a signal and determines that it poses a threat, it works quickly to alert other parts of the brain. Subsequently, the body releases hormones, including cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline, which help activate the autonomic nervous system by stimulating the sympathetic nervous system and depressing the parasympathetic nervous system. Evolution thinks for you. As soon as you’re in danger, you’re already responding.

After being startled, the body goes through a short period of shock. During this limited window, a thorough assessment of the perilous situation may be made. This is because the prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain, is also performing at peak efficiency and assessing the issue at this moment. This is where much of our awareness takes place. To put it another way, while our conscious mind is still “thinking,” our subconscious mind is already doing.

A crude, unintentionally assessed “situation sketch” is also sent to the cerebral cortex from the amygdala. We’re at the point when people start thinking about whether to run away or fight. The scenario is only “defused in the mind” if the prefrontal cortex relays back to the amygdala that there is no risk or that the danger has been averted, like when we understand the snake is a fake and laugh at our fear. According to LeDoux, it is this loop that allows for the experience of conscious fear.

When the messengers go on strike

Neurotransmitters play a crucial role in signal transmission because they act as messengers in the brain. They serve as intermediaries between the synapse of many types of neuronal nerve cells. Certain types of neurotransmitters are more active in certain parts of the brain. Most people only know dopamine as a happy messenger, yet it is one of the most well-known neurotransmitters and responsible for a variety of functions. The amygdala, on the other hand, uses it to create fear. A higher level of dopamine release in the amygdala correlates with a more intense fear reaction.

Serotonin is another neurotransmitter that has been discovered. Anxiety, concern, and fear develop when this neurotransmitter fails to “get through” or is missing during anxiety formation, which takes place in the brainstem. As a result, low levels of serotonin might contribute to feelings of depression and irritability.

Other neurotransmitters, like GABA and norepinephrine, also contribute to the emergence of fear. It’s not only the amount of information that matters, but also whether or not the neurons and synapses receive and process it. Mood swings, as well as shifts in behavior and thought, may have many different origins.

Anxiety disorder: The enemy in your own head

Anxiety and panic disorder symptoms may strike anywhere, including the metro, the theater, and the grocery store checkout line. In doing so, the worry multiplies like a virus, invading and eventually taking over even more aspects of daily life. If anxiety attacks become too severe, people may start avoiding the triggers altogether. However, the more people isolate themselves, the worse their anxiety gets, until finally, for many, their own homes become their only refuge.

Discordant spirit

We talk about an anxiety disorder when rational thought is replaced by irrational fear. Approximately one-quarter of the population experiences such pathological anxiety at some point in their lives; women are more likely to be affected than males. They often manifest in the early adult years in response to a stressful event, whether it is an accident, the death of a loved one, or “just” stress. In our daily lives, we don’t need to be scaredy-cats for any of them to increase our susceptibility to anxiety-inducing events.

It’s common for the phase to end on its own. Repeated episodes of unwarranted worry over an extended period of time only serve to exacerbate the situation. As much as possible, they steer clear of anything that can set off their anxiety. Anxiety episodes and generalized avoidance put a significant damper on daily life, making it difficult to take any kind of action. It’s possible that a variety of clinical presentations of persistent anxiety disorder might emerge: Some examples of these conditions include social phobia, particular phobia, and panic disorder.

Wide range of phobias

Everyone is familiar with the hundreds of different types of phobias. There are both logical and irrational phobias, as well as particular and social phobias of things like certain locations or animals. Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is the fear of really long words, and the term is a scientific joke. Simply letting people know about the illness might send people into a state of complete and utter panic.

The majority of phobias seem rather ridiculous, no? The inability to fit in socially is a major challenge for those with anxiety disorders. Because fear is such a personal sensation, we frequently dismiss the fears of others or believe that our own fears are met with good-natured laughter. However, phobias lose all of their comedic value if they begin to control a person’s daily life. This occurs when people attribute negative emotions to situations that provide no real threat. Agoraphobia, the fear of locations or circumstances from which there is no easy escape, is a common phobia.

Having a fear of having a fear

The trouble with anxiety disorders is that it’s possible to develop a fear of fear itself, a condition known as phobophobia. There is a domino effect that leads to further problems. It’s possible for this to occur since our brains readily generalize our fears. What’s meant to keep us safe in a world full of new threats has the potential to become a mental illness.

When someone has had a panic attack, for instance, they may worry that the fear may happen again in a similar setting. The other three options are that (1) no panic occurs when a comparable circumstance develops, and (2) everything works out. Or maybe we manage to dodge them altogether. Or maybe the impending fear inspires the next assault. In this case, the fear might become a self-fulfilling prophecy, manifesting itself in ever-increasingly threatening circumstances, from which there is no real way of escaping.

Even if such fears are difficult to ignore, it may be years before a person is diagnosed with an anxiety condition. The reason is that the onset of physical symptoms in a panic disorder may be sudden and severe. A person with this disorder may experience a wide range of symptoms, from an incorrect diagnosis to the firm conviction that they are about to die. Because of the nature of a brain-based illness, victims often see a succession of medical professionals without resolution.

Insufficiency and excess in mental processing

It’s common for people to freak out despite the obvious lack of threat. However, why is it that the conscious mind has long understood that a certain circumstance is harmless, while the subconscious mind continues to fail to accept it as such? With anxiety disorders, two things go wrong in the brain: the amygdala speeds up, while the prefrontal cortex slows down. What this implies is that our subconscious’s fear center is always overactive, sending the body the message that it is in a hazardous circumstance even when there is none. That it isn’t, the prefrontal cortex at that time doesn’t recognize it, therefore it doesn’t tell the amygdala to relax.

Numerous neurotransmitters in the brain are likely playing a role, since they are out of whack. A panic attack may be triggered by a variety of factors, including an imbalance in neurotransmitters, exposure to a stressful event, persistent stress, or an unhealthy way of life. Patients with panic disorders, for instance, have lower levels of anxiety that trigger GABA.

The gene responsible for fear

Anxiety is a complex emotion, and its intensity is influenced by a wide range of factors. One’s own lifestyle and attitude, a traumatic event, and even one’s own genetics may all play a role in exacerbating an existing fear and turning it into a phobia. For the simple reason that our ancestry already tells us whether or not we would be vulnerable to fear-based disorders.

The probability of inheriting an anxiety condition is three- to six-fold greater in some families. Gene variations often change the brain’s messenger system in a manner that makes us more vulnerable to fear disorders. Numerous variations in this kind of gene have previously been discovered. However, they are not independent factors; rather, they are the result of a number of genes interacting in a complicated manner, leading to a condition known as a complex genetic illness. Genetic risk is the result of several genes interacting in complex ways.

Still, having a genetic predisposition doesn’t guarantee that the illness will manifest. The fact remains, nevertheless, that they are a necessary requirement. An estimated 50 percent of the onset of affective and schizophrenia illnesses may be traced back to genetics. Many aspects of one’s way of life, such as the use of alcoholic beverages, contribute to the remaining 50%.

Patterns in education influence us

In addition to our genetic makeup, our development may be shaped by the experiences we encounter as children. This is because children often mimic their parents’ behaviors and attitudes. In the case of a lack of fear of heights, for instance, this trait may be imparted to offspring by seeing their parents’ own attitudes and actions. They may teach their child to fear heights by reacting wildly and panicking when exposed to dangers like cliffs and other vertical surfaces.

Is fear inherited?

Is it also possible to pass on a learned fear? In 2013, American researchers found that mice were able to pass on their acquired fear to their offspring. Researchers Brian Dias and Kerry Ressler from Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta used electric shocks to teach mice to develop a fear response to the aroma of cherry blossoms. After mating the animals, they created hybrids. It turned out that the smell of cherry blossoms sent fear into the hearts of the next two generations as well.

The biological inheritance of experiences is shown here, at least in mice. The epigenome is responsible for this. These tethers to DNA regulate gene expression in numerous ways. It was shown that chemical modifications to the genes responsible for odor recognition in mice might affect the gene’s activity. Extensive investigation is still needed to see whether the same holds true for people. This, however, would imply that parents aren’t the only ones passing on their fear to their children.

How to face fear?

Concerning anxiety disorders, the prognosis is typically quite excellent. The first step in getting help for anxiety disorders is realizing that you have a problem and trying to fix it on your own if you can. But if it doesn’t work, or if their anxiety is so bad that regular living is difficult or impossible, they should see a therapist or psychiatrist.

Realize the significance of your way of life. It follows that if a person’s pathological anxiety worsens, making adjustments to their regular routine might be helpful. First, it’s important to minimize stress; regular exercise, even for 30 minutes a day, may help a great deal. A balanced diet and avoiding using substances like alcohol or drugs to numb one’s fears are also crucial.

Anxiety patients might utilize the tactic of “desensitization” to target and lessen their episodes of anxiety. Similar to how the immune system learns to stop responding to an allergen, facing a fear may teach the brain to minimize the reactions. It’s necessary to confront fears and actively seek out “dangerous” circumstances, however. Psychotherapy takes advantage of this as well.

Hold your ground rather than run away

Sitting it out is the best option if the anticipated fear materializes. The best thing to do if you’re scared of the seemingly hopeless scenario on the train is to stay seated and keep going till your nerves calm down. Getting out of there doesn’t imply you’re a failure or have to quit. It’s best to give it another go once you’ve had a chance to collect your thoughts and the initial worry has worn off. In most cases, the human body just can’t withstand prolonged exposure to high levels of stress. Slowly but surely, calmness settles in, and the first step is made.

Our amygdala, the fear center of the brain that monitors threats, eventually concludes that we are safe. This is due to the fact that the fear memory has a high learning capacity; otherwise, anxiety disorders wouldn’t exist. An area of the brain reconditions the individual by writing over the previous pattern. Eventually, the brain “perceives” the once unpleasant circumstance as neutral, and the panic response to it fades.

When life is a constant minefield

It’s time to seek professional aid after you’ve exhausted all other options for resolution. The sooner an anxiety problem is identified, the better it may be treated, but for many individuals, this comes much too late. Additionally, there are additional positive indicators of achievement. Psychotherapy and medicine are often used together to treat patients. Using cognitive-behavioral therapy, one may also face their fears head-on.

Medications assist in altering the brain’s neurological circumstances in such a manner that there are fewer pure physical fear impulses if patients are unable to manage their anxiety via behavioral changes. Drugs like antidepressants and benzodiazepines are widely used and well understood. Both medications elevate levels of the relevant neurotransmitters.

Medicine as treatment

Although these medications are often the last choice for patients with severe anxiety, many patients report limited effectiveness and significant adverse effects. Researchers are always looking for novel treatments, but no effective psychopharmaceutical has been created as of yet. But gradually, some researchers are starting to focus on something “different”: the components of various drugs of abuse.

Because psychotropic mushrooms and ketamine, two common hallucinogens, may provide fresh promise in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Many years ago, the use of these chemicals was outlawed in the field of drug development. Yet researchers are examining them in depth to see whether they may really help people get well. Tiny dosages of ketamine given intravenously may benefit very ill individuals. It has come a long way, but it has not yet been widely recognized as a legitimate medical treatment. Looking into adverse reactions and addiction will need more study time and resources over the next several years.