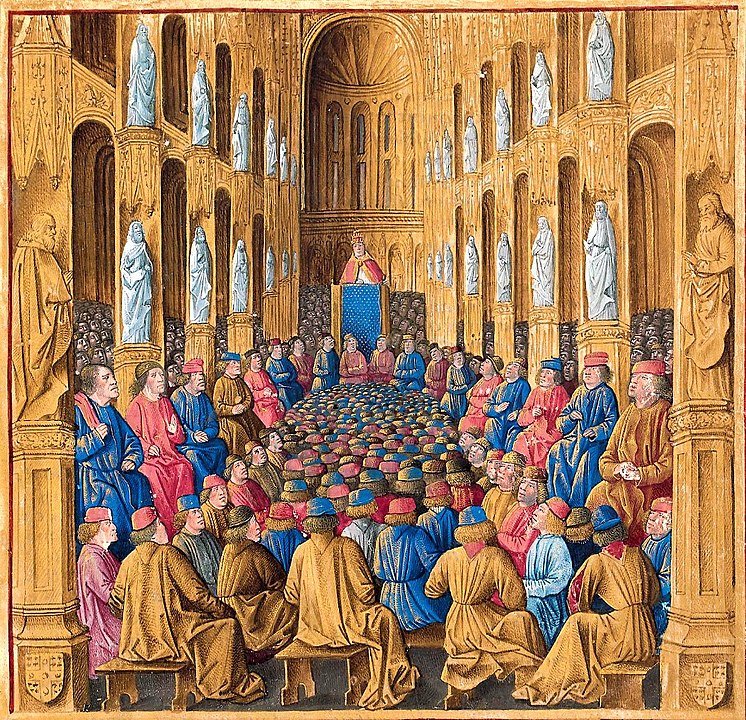

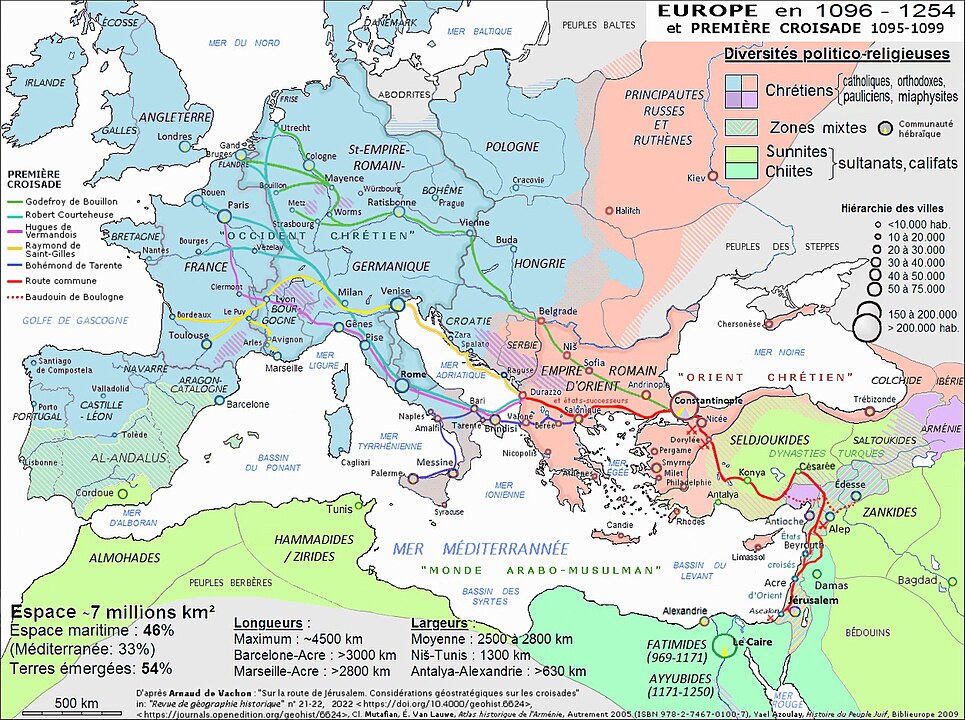

In response to Pope Urban II’s call in 1095 to liberate the Holy Land, Christian armies from Flanders, Lorraine, Burgundy, and southern Italy converged on Constantinople during the First Crusade. Led by Godfrey of Bouillon, they joined forces with Alexios I Komnenos to reclaim former Byzantine territories conquered by the Seljuk Turks. The recapture of Nicaea, Antioch, and finally Jerusalem (on July 15, 1099) by the Crusaders allowed for the creation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, as well as the Principality of Antioch, the County of Edessa, and the County of Tripoli.

East and West in 1095

While the West was undergoing significant transformations in the 11th century, the East was also in a state of relative instability. The Byzantine Empire, under the Macedonian dynasty, had managed to regain a certain level of peace and even relative splendor until the 10th century.

However, at the start of the next century, the Byzantines found themselves besieged once again (by Normans, Pechenegs, and Bulgarians), and despite relatively good relations with the Fatimids, they had to yield to the advancing Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, opting to abandon part of Anatolia to prevent their core (Constantinople) from being directly threatened. Moreover, their relations with the West had been deteriorating since the Schism of 1054. Fortunately, the rise of Alexios I Komnenos, who defeated the Pechenegs, brought some hope to the Eastern Romans.

In the Muslim world, the caliphate had already fractured (in the second half of the 10th century) into three competing entities: in the West, the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba (which will not be directly relevant here), but more importantly the other two rival caliphates, the Shia Fatimids of Cairo and the Sunni Abbasids of Baghdad. The former were on the rise in the 11th century, with their territory extending into Syria-Palestine and the Holy Places in the Arabian Peninsula! The latter, however, had been weakened since the previous century by various dynasties such as the Buyids and by Turkish influence within the army.

It was the Turks themselves, specifically the Seljuks, who gradually took control of the region (Iran, Iraq, Syria-Palestine, and even Anatolia thanks to their victory at Manzikert). While they swore allegiance to the Caliph of Baghdad (who granted them the title of sultan), they held most of the real power. However, they too became divided after Malik Shah’s reign (he died in 1092) due to internal conflicts. Thus, on the eve of the Crusade, the East was deeply divided and weakened.

In the West, as mentioned earlier, this period marked the assertion of the Church’s independence following the Gregorian Reform, despite the ongoing latent conflict with the Holy Roman Empire resulting from the Investiture Controversy (starting in the 1070s). In France, the Capetian monarchy was slowly gaining strength against the great lords, but on the eve of the Crusade, King Philip I had other concerns—he had been excommunicated for remarrying!

In England, the country had been Norman since the conquest by William the Conqueror in 1066. The Normans were expanding rapidly, even into the Mediterranean: just a few years before Urban II’s call, they had conquered southern Italy and Sicily! Italy itself was torn by conflicts between the Pope and the emperor, but different cities were emerging, based on trade: Amalfi at first, then Venice, Pisa, and Genoa. Lastly, Spain had served as a testing ground for the Crusade with the Reconquista, the first victorious step of which led to the capture of Toledo in 1085.

First Crusade of the Barons and the People’s Crusade

Urban II’s call met with unexpected success! It did not appeal particularly to temporal rulers, as no major sovereign participated, but it did resonate with the common people. This is what came to be known as the “People’s Crusade” (or the Peasants’ Crusade), which left a lasting impression. Led by Peter the Hermit (a preacher), Walter Sans-Avoir (a knight), and a few other obscure leaders, it was primarily made up of Frenchmen, estimated at several thousand strong (some reports speak of 15,000, an enormous number for the time).

This was a crowd of poor people, driven by a sort of mystical fervor, if not fanaticism, that swept across Central Europe starting in 1096. Their path was quickly marked by pillaging and persecution, especially against Jews, in the Rhineland and as far as Hungary. This “People’s Crusade” (far from peaceful) reached the walls of Constantinople, much to the dismay of the Byzantines, who were shocked by these unorthodox methods.

Meanwhile, the “Barons’ Crusade” was organized more slowly, but unlike the People’s Crusade, it was directly under papal authority through the legate Adhemar of Le Puy. This First Crusade split into four armies: that of Raymond of Toulouse (who had fought in Spain) and the papal legate, the Flemish army of Godfrey of Bouillon, the army of Philip I’s brother Hugh of Vermandois for Île-de-France and Champagne, and the Normans under Bohemond of Taranto.

Baldwin of Boulogne (Godfrey’s brother) and Tancred (Bohemond’s nephew), who would become significant figures in the Latin presence in the East, should also be mentioned. The knights took two different routes—by land and sea—and also headed to Constantinople. For all, the journey was perilous: shipwrecks, attacks by bandits in uncontrolled territories… The beginnings of the First Crusade were far from easy, and God did not seem to have chosen an easy path for his pilgrims!

Negotiations with Alexios I Komnenos and the First Battles

The Byzantine emperor viewed the unruly “People’s Crusade” camped outside his walls with great displeasure. He decided to transfer the pilgrims across the Bosporus. The Seljuks awaited them at Civetot and massacred a large number of them! Peter the Hermit disappeared (his fate remains unknown), and Walter was killed along with 20,000 other peasants.

It was, of course, not as easy for Alexios Komnenos to deal with the powerful barons in the same way. The barons, camping outside the city, grew increasingly insistent and more threatening when they learned from a few survivors that the emperor had delivered the defenseless pilgrims to the Turkish armies. Negotiations lasted several weeks during the spring of 1097, and finally, an agreement was reached (a promise by the crusaders to return Antioch to the Empire, and an oath of allegiance refused only by Raymond of St-Gilles). The barons then crossed the Bosporus as well.

The Turks, still divided, were caught off guard this time. Nicaea was besieged and taken on June 19, 1097, and then returned to the emperor. On July 1, the crusaders defeated the Turks at Dorylaeum, after which the Turks began practicing a scorched-earth policy. This battle highlighted the stark difference between the two combat traditions, a difference that would persist throughout the Crusades: the Franks favored heavy cavalry charges, while the Turks preferred harassment and mounted archers.

The Difficult Journey to the Holy Land

The real difficulties for the crusaders began; though they no longer faced substantial military opposition, they encountered a “new world” they were unaccustomed to. Heat, food and water shortages, and a lack of fodder increasingly took their toll, and the desolate lands of Anatolia weighed heavily on the pilgrims’ morale. Some even resorted to drinking the blood of horses. Tensions grew within the crusader leadership, as the pope’s legate was unable to assert his authority. After two more clashes with the Turks at Iconium and Heraclea, the crusaders decided to split into two groups in September 1097.

The bulk of the army moved toward Caesarea to avoid the Cilician Gates; by the end of October, they were in front of Antioch, which the Turks had taken from Byzantium in 1085. The second army, led by Tancred and Baldwin of Boulogne (brother of Godfrey of Bouillon), passed through Cilicia. Baldwin then responded positively to a call for help from the Armenians of Edessa, enemies of the Turks and rivals of the Byzantines, who opened the city to him. The crusader became the city’s governor, creating the first Latin state: the County of Edessa, in March 1098.

The siege of Antioch began in October 1097. The city was governed by a Seljuk emir, vassal to the emir of Aleppo. The siege was long and difficult, with many problems: Turkish sorties, supply shortages, a lack of siege machines, desertions, and rivalries among the barons. It took the complicity of a Christian convert to Islam, an Armenian, to infiltrate the city: Bohemond entered Antioch on June 2, 1098. Many Turks were massacred, but some remained protected in the citadel. Worse still, the crusaders found themselves besieged within the city they had just captured by Turkish reinforcements led by Kerbogha of Mosul!

The situation grew increasingly dire: famine, disease, and even rumors of cannibalism among the crusaders spread. The liberation of the Holy Sepulcher seemed like a distant memory. Then, opportunely, the Holy Lance was discovered in the cathedral of Antioch, boosting morale. The crusaders launched a sortie and took advantage of dissensions within the Turkish command. On June 28, 1098, they achieved victory. The great victor was the Norman Bohemond of Taranto, who claimed and obtained the governance of the city despite opposition from Raymond of St-Gilles and especially the Byzantines, who had expected the city to be returned as promised. Tensions flared between the emperor and the Frankish barons.

Oh Jerusalem!

The ordeal endured to capture Antioch, along with the troubled journey and the massacre of the People’s Crusade, had nearly made the primary (and perhaps sole) goal of the warrior pilgrimage — Jerusalem — forgotten. The barons continued to quarrel (some even seeking to carve out fiefs in the region), while the Holy City had been taken from the Turks by the Fatimids in 1098. But it was the people who revived the spirit of the Crusade: the “Tafurs,” common folk, many from Peter the Hermit’s crusade, rekindled the pilgrimage spirit and forced the barons to resume their march at the beginning of 1099. In the meantime, the papal legate Adhemar of Le Puy had died on August 1, and the crusade truly fell into the hands of temporal powers, to the detriment of the Church.

Raymond took command of the army, as Bohemond remained in Antioch. He first attacked the ports and established supply lines with the Byzantine and especially the Genoese fleets; however, he avoided the best-defended forts and cities. While Tancred was tasked with liberating Bethlehem (captured on June 6), the bulk of the army reached Jerusalem on June 7, 1099.

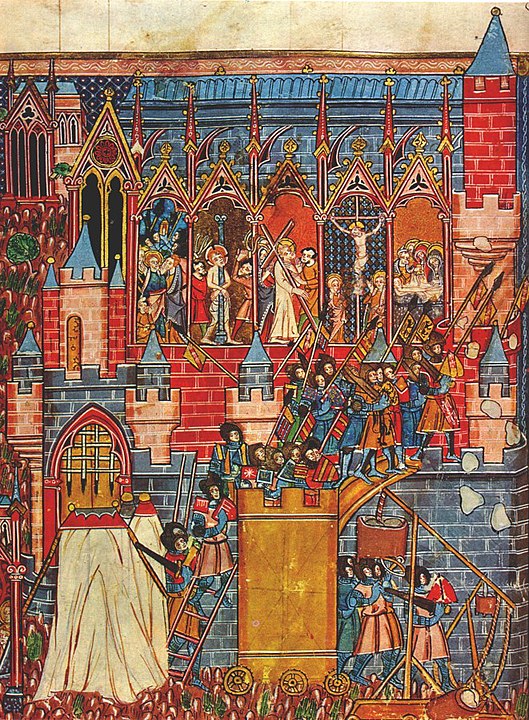

The emotion was overwhelming! After so much effort, the pilgrims finally reached their goal: they knelt and prayed at the foot of the city walls, much to the astonishment of its inhabitants. The crusaders even hoped for a miracle to allow them to liberate Jerusalem without a fight. When no miracle occurred, they launched an assault on June 13 but failed due to a lack of equipment (ladders in particular). The Frankish leaders then decided to organize better: Raymond settled in the south; the Lorrainers, Normans, and Flemings divided the west and north without mingling. They began constructing siege machines, likely with advice from the Byzantines, accumulated over previous years, but there was a shortage of wood in the region, and still no miracle.

Fortunately, by June 17, the capture of the ports showed its value: reinforcements arrived via Genoese and English sailors, who brought the necessary equipment despite the threat of the Fatimid fleet. On the defenders’ side, preparations were also underway, including the use of Greek fire, inherited from the Byzantines. The long preparations did not prevent actions, especially those of spies; those captured in the crusader camp were catapulted back to Jerusalem (some smashed against the walls).

The preparations lasted a month, with continued hardship among the besiegers. It was decided to prepare for the final assault by ensuring God’s full support: a public fast of three days was declared, and on July 8, a procession was held. Barefoot but armed, the pilgrims marched around the city. They passed so close to the walls that they were shot at and urinated on, while the Muslims spat on the crosses.

On July 10, a siege tower was positioned at a weakly defended spot, while another advanced slowly due to difficult terrain. The mangonels began bombarding the walls, followed by the battering ram. The general attack began on July 13, but the crusaders only penetrated Jerusalem on July 15, initiating a great massacre.

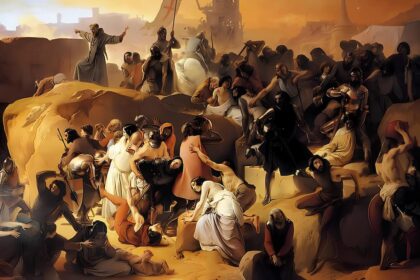

The First Crusade Ends in a Bloodbath

Christian or Muslim chroniclers all agree that the capture of Jerusalem was carried out in a bloodbath: street fighting lasted two days, with reports of heaps of dismembered bodies and severed heads, and inhabitants massacred in both mosques and synagogues. One chronicler recounts that blood rose to knee level in the fury of purifying the “Solomon’s Temple” (the Al-Aqsa Mosque). For this unleashing of bloodthirsty violence was not “gratuitous”: it was the result of several years of fanatical pilgrimage for the liberation of the Holy Places, of Christ’s tomb, which had to be purified by blood.

Moreover, we must also put into perspective the figures given by chroniclers on both sides, and their descriptions: the city was not emptied of its inhabitants at the end of the fighting, and while the violence was indeed terrible (it would mark generations to come, particularly Saladin), it was not unprecedented for the time…

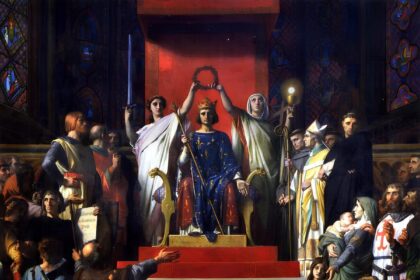

The goal of the First Crusade was achieved: Christ’s tomb was liberated, and the victors could intone the Te Deum there. But now, what to do? Most of the crusaders would return to the West, but those who remained would have to organize themselves. This would lead to the creation of the Latin States of the East, in which many European sovereigns would invest themselves: the German Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, King Richard the Lionheart of England, or the future Saint Louis.