The First White Terror during the French Revolution was a violent anti-Jacobin reaction during the Thermidorian Reaction (1794–1795). After Robespierre’s fall on 9 Thermidor Year II (27 July 1794) and especially after the failure of the revolutionary attempts on 12 Germinal (1 April 1795) and 1 Prairial (20 May 1795), the royalists, or “whites,” led a violent repression against the Jacobin sans-culottes. This White Terror, the counterpart to the “red” Terror of the sans-culottes during the “Robespierrist” regime, persisted intermittently throughout the Directory.

A Divided Revolutionary France

Although the White Terrors were less deadly than the revolutionary terror, the excesses committed after Robespierre’s hasty execution without trial and after Napoleon’s second abdication were far from insignificant, even if they occupy only a modest place in official history. The most terrible inclinations of humanity were on display, mirroring the fall of the monarchy, showing not only the extremes of political passions but also personal vendettas exploiting the disorganization of the State to act freely without constraint.

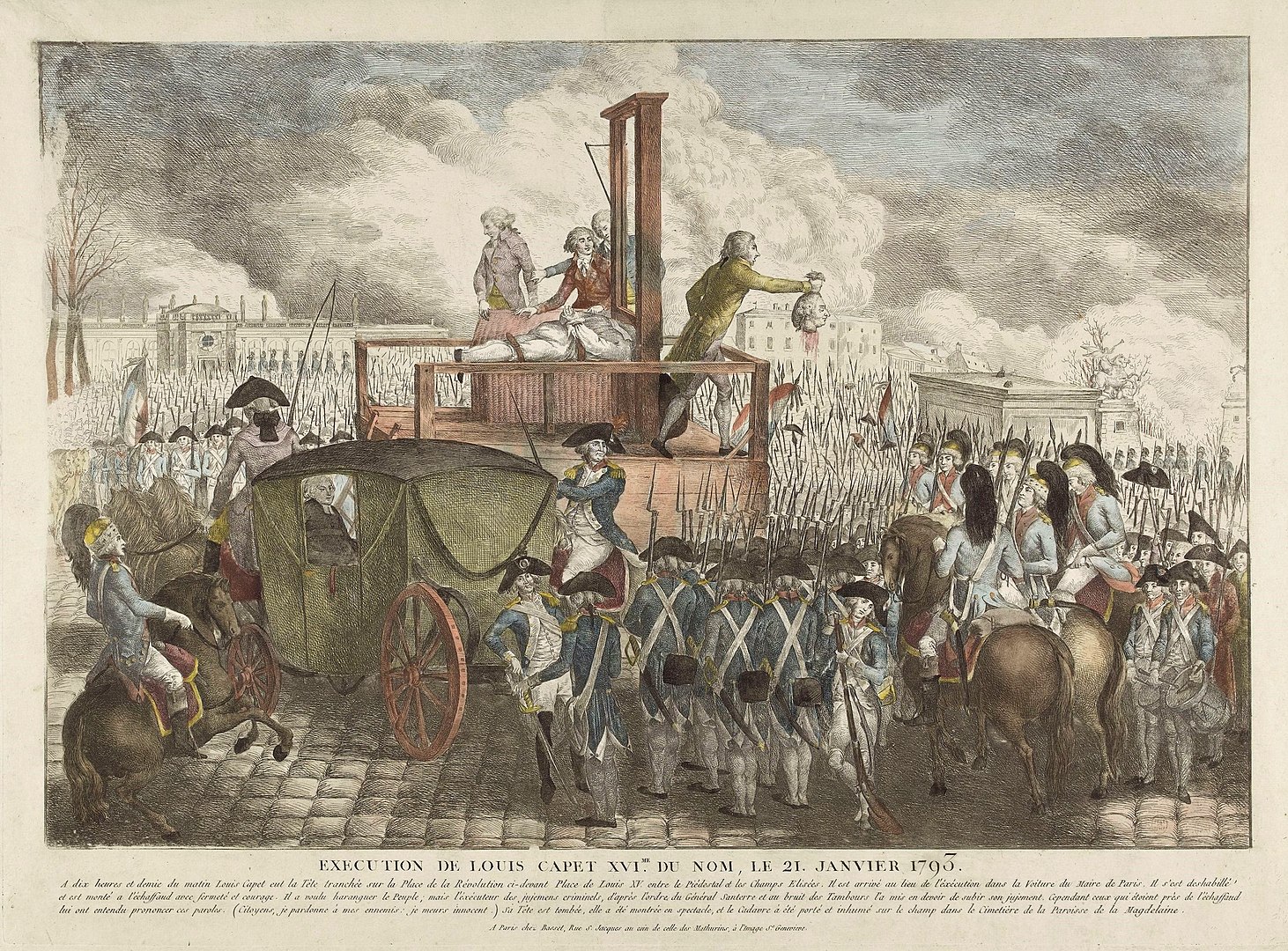

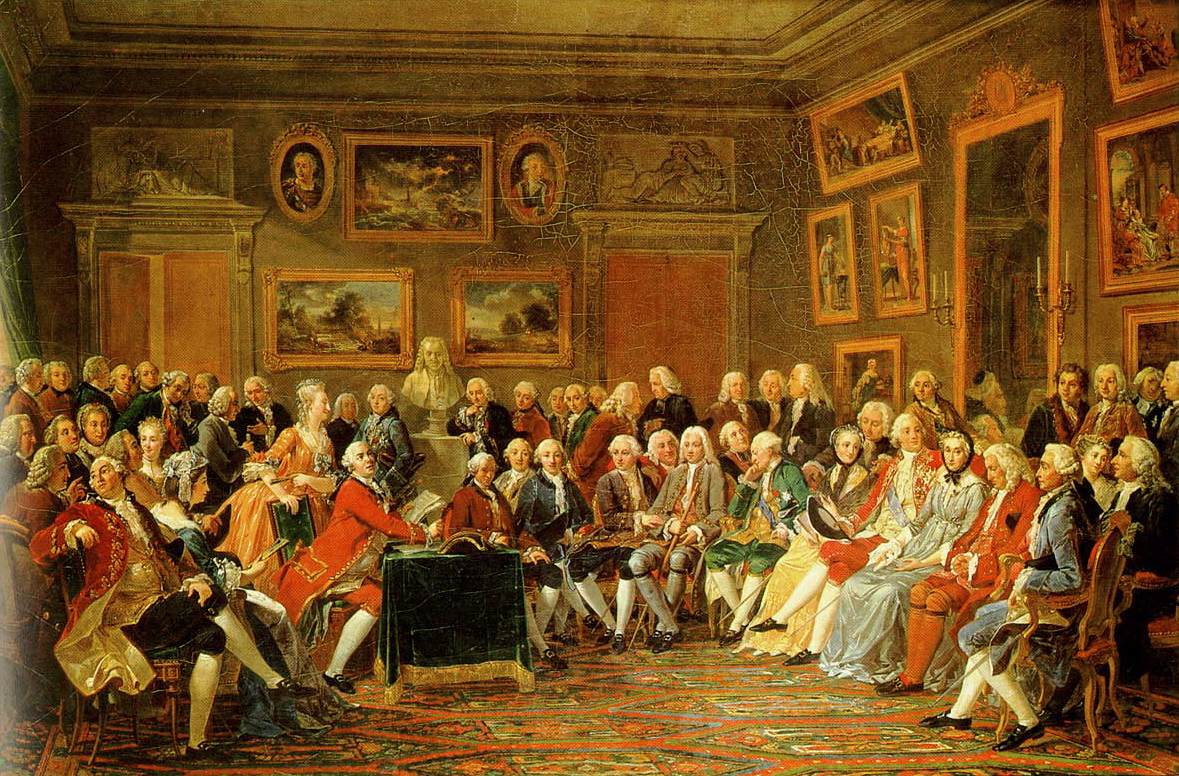

To understand the White Terrors, one must return to the beginnings of the Revolution. The oppositions were not only political but also religious. Protestants, still numerous, especially in the Cévennes and southern France, were generally in favor of regime change (Rabaut Saint-Etienne was a Protestant pastor from Nîmes), whereas Catholics often leaned toward the Ancien Régime. Among Catholics, the Jansenists were more inclined toward the new order than the Jesuits, meaning religious disputes reinforced political conflicts.

In several southern cities, bloody clashes broke out between the two sides. This was particularly true in Nîmes, which had a significant Protestant community supported by their co-religionists in the Cévennes. Through somewhat dishonest maneuvers, Catholics managed to take control of the National Guard and appoint an aristocrat as mayor. The supporters of the Ancien Régime armed themselves with axes and pitchforks to hunt down Protestants, known as “black clothes.” They hoped for the support of the Guyenne regiment stationed in the city, but it remained loyal to the constitution.

Fights broke out between soldiers and the National Guardsmen, the former wearing the tricolor cockade, the latter the white cockade. A royalist armed insurrection erupted but was crushed by the army, which assaulted a tower where the rebels had barricaded themselves with a small cannon. Contrary to their expectations, the Catholics of Nîmes received no help from other southern cities; on the contrary, they antagonized the Protestant Cévennes, whose National Guardsmen camped on the outskirts of the city. These events in June 1790 led to massacres, interpreted differently depending on the side. The Catholic movement failed but left lasting scars on the collective memory.

Two early attempts to unite anti-Revolutionary forces connected to émigrés occurred in July 1790 and February 1791 in Vivarais (Jalès camp). In July 1792, an even more openly monarchist conspiracy formed around one of the authors of the previous attempts. The goal was to organize an uprising of southern Catholics, fueled by hatred of Protestants. The conspirators seem to have overestimated the strength of the antagonisms. In any case, their gathering was dispersed by the army, and many of the fugitives went underground, where they engaged in banditry.

Later, the nascent Republic faced a royalist insurrection in the West (Vendée, Brittany, Pays de la Loire, Normandy). These uprisings, motivated primarily by religious reasons (rejection of the constitutional clergy), secondarily by opposition to conscription, and finally by the abolition of communal lands (sold as national property, depriving the poorest rural inhabitants of their main resources), were much bloodier than the White Terrors.

In addition to these uprisings, starting in June 1793, after the fall of the Girondins, the Committee of Public Safety also had to contend with federalist revolts in Normandy (Caen), Bordeaux, Lyon, and the south, where the port of Toulon was handed over to the English. These revolts brought Girondins and royalists closer together, at least in Lyon and Toulon, united by their common hatred of the Jacobin Montagnards in power in Paris. It is important to note that not all southern inhabitants were pro-monarchy. The role of the Marseille volunteers in the fall of the monarchy in August 1792 and the popularization of the song that would become the French national anthem are significant reminders of this.

The intensity of opposing passions in the south partially explains the events of the White Terrors. While the Marseillais played a significant role in the storming of the Tuileries, and the young revolutionary hero Agricole Viala was killed by royalists in 1793 on the Rhône near Avignon, Marseille remained in the hands of moderates, who imprisoned and guillotined republicans even before the Girondins were overthrown. Later, the bloody repression of royalist and federalist uprisings sowed the seeds of future vengeance.

The period following Robespierre’s fall saw not only the rehabilitation of the surviving supporters of Danton, Hébert, and the Girondins but also the return from exile of some royalists who continued to hide while benefiting from relaxed surveillance to resume their old plots. This was particularly the case with Imbert-Colomès in Lyon; compromised in the bloody suppression of a food riot in 1789–1790, he had to flee after his house in Lyon was destroyed by a popular uprising. Far from being a time of calm, this period was one of heightened tensions. None of the involved parties, whether the remaining Montagnards or their rehabilitated adversaries, interpreted the fall of the “tyrant” the same way.

The Thermidorian Reaction

The Thermidorian Reaction was characterized by the abandonment of policies favoring the popular classes (such as the law of the maximum) and a relaxation of revolutionary discipline. However, those who brought down Maximilien Robespierre, out of fear of the guillotine, often due to their own excesses and plundering, had no intention of ending the Terror. They were carried further by events than they initially intended. Evidence of this is that the most fervent extremists of the Committees remained in place, at least for a time. Therefore, portraying the movement against “The Incorruptible” (Robespierre) as a movement against the Terror is, in part, a historical falsification; most serious historians of the Revolution have already corrected this biased view.

In the factional struggles that resurfaced, those currently holding power, often newly wealthy and free from fear, seized every opportunity. They thought their time might be limited, as the revolutionary spirit was far from subdued, as demonstrated by the events of Germinal and Prairial. During these days, riots twice invaded the Convention; a deputy (Féraud) was assassinated, and his head was presented on a pike to President Boissy d’Anglas.

Féraud, however, was a victim of mistaken identity—he had been taken for Fréron, the leader of the gilded youth! This helps explain the moral decline and the hatred the new elite felt toward the republicans. These “muscadins,” as they were called, wielded leaded clubs disguised as canes to beat anyone they suspected of being part of what they called the “tail of Robespierre.” It was in this context that the first “White Terror” began.

The press, having regained some freedom, fanned the flames. Moderate and royalist newspapers launched attacks on the terrorists, as did the Hébertist pamphleteers (like Gracchus Babeuf), at least until mid-November 1794, when the Babouvists reallied with the Jacobins. Louis Fréron, who had represented the Convention in the South alongside Barras in 1793, had distinguished himself there by his violence and thefts.

From September 11, 1794, he resumed publishing L’Orateur du Peuple, a reactionary propaganda outlet, in which he displayed a virulent anti-Jacobinism—entirely opposite to the ferocity he had previously directed at royalists. Fréron no doubt hoped to make people forget that, in the same newspaper in 1791, he had loudly dreamed of storming the Tuileries, toppling the monarchy, and wished for Marie-Antoinette to be tied by her hair to a horse’s tail, to suffer the fate of Frédégonde.

He also likely wanted to make people forget that he had boasted in his letters about having massacred dozens of counter-revolutionaries without trial in Marseille and Toulon, and that his role in the events of 9 Thermidor was primarily to avoid punishment for his crimes. Alongside this fanatic, now claiming he would burn down the Saint-Antoine district, royalist Méhée de Latouche published the pamphlet La Queue de Robespierre, and Ange Pitou spread royalist songs in the streets. These examples are just a small reflection of the many counter-revolutionary publications that appeared at the time (Le Messager du soir, Le Postillon des armées, L’Éclair, L’Historien, Les Nouvelles politiques, Le Véridique, Le Rôdeur, Le Précurseur, La Feuille du jour, Le Courrier républicain (poorly named), Le Gardien de la constitution (a constitution they dreamed of overthrowing), La Quotidienne…).

Verbal and physical violence against anyone even remotely resembling a Jacobin increased. In Paris, Tallien and Fréron organized gangs of muscadins. Two to three thousand of these dandies, made up of suspects released from prison after Thermidor, deserters, draft dodgers, journalists, artists, clerks, brokers, and small tradesmen, mostly living on the right bank and nicknamed “Collets Noirs” (Black Collars) due to their attire—a tight coat with a black velvet collar (mourning the death of Louis XVI), with 17 pearl buttons (in honor of Louis XVII), tails cut like a cod’s tail, breeches tight at the knee, and braided hair tied back by hairpins—paraded their rejection of the revolutionary order by waving their leaded clubs.

Gathered around singers and composers like Pierre Garat, François Elleviou, and Ange Pitou, dramatist Alphonse Martainville, and publicist Isidore Langlois, and led by adventurer the Marquis de Saint-Hurugue, they became increasingly openly anti-republican. They stirred up loud disturbances in the Palais Royal neighborhood, making noise in the streets while singing Le Réveil du Peuple, a counter-revolutionary song.

They met in royalist cafés, read the aforementioned newspapers, disrupted theater performances by heckling actors considered terrorists, imposing readings or songs, and attacking anyone whose readings, words, or appearance remotely resembled that of the Jacobins. They also hunted down busts of revolutionary figures, forcing the Convention to remove Marat from the Panthéon and throw him into a sewer on February 8, 1795. Finally, they multiplied clashes, some of which escalated into brawls, murders, and rapes of Jacobin women.

Fights between the gilded youth and republicans, Jacobin or otherwise, multiplied, particularly with soldiers on leave or at the Hôtel des Invalides. One notable incident took place on September 19, 1794, at the Palais-Égalité (Palais-Royal). Using these violent incidents as a pretext, the authorities closed the Jacobin Club in November 1794. Even Girondin Louvet de Couvray, who denounced both royalists and Jacobins in his newspaper La Sentinelle, was attacked by young royalists in his bookstore-printing shop at the Palais-Royal in October 1795.

The Jacobins, facing hostility from both moderate republicans and royalists, and the people of Paris, suffering from famine during the harsh winter of 1794-1795, partly due to the Convention’s liberal policy of ending the price cap on grain, responded by revolting. However, the insurrections of 12 Germinal and 1 Prairial Year III (1795) failed. The authorities ordered the disarmament of the terrorists, confining them to their homes; 1,200 Jacobins and sans-culottes were arrested. These were the last popular uprisings in Paris until the Revolution of 1830. Rather than be guillotined, the last Montagnards in prison committed suicide with a single knife, which they passed from one to another. Meanwhile, the Committees were purged of the remaining terrorists.

The Revenge of the Royalists

Taking advantage of the Thermidorian reaction, with the return of refractory clergy and the influx of émigrés, for whom new legislative measures cautiously opened the door, spontaneous vengeance movements by royalists, families of victims of the Jacobin terror, and fanatical Catholics developed in 1795, particularly in the southeast of France, especially in the Rhône Valley. These movements targeted former Jacobins, sans-culotte militants (called “terrorists” or “mathevons” in Lyon), as well as Protestants. The recall of former Girondins led to the return of those who had handed Toulon over to the English.

Many individuals who had left well before the May-June 1793 crisis, true émigrés disguised as Girondins, took advantage of the opportunity to return, threatening purchasers of nationalized property and stripping them of the fruits of their labor. Delegates from the new Committee of General Security of Marseille even went aboard the British fleet to negotiate the restoration of the monarchy in exchange for the disarmament of French fleets and arsenals, a blatant act of treason. The Convention was soon forced to exclude émigrés and traitors to their country from benefiting from return laws.

Exploiting peasant reactions, popular revenge, and counter-revolutionary actions that created a climate of violence, monarchist leaders rallied around them discontented young men, former federalists, deserters, and criminals. The English agent Wickham, based in Switzerland, established a propaganda agency in Lyon that recruited counter-revolutionaries, such as Imbert-Colomès, and prepared a new insurrection with Précy, who had already commanded the federalist uprising in Lyon in 1793. They facilitated desertion and encouraged refusal to conscription to weaken the republican armies. Republican generals were imprisoned, others were dismissed or demoted, as was the case with Bonaparte, while armed bands liberated arrested émigrés.

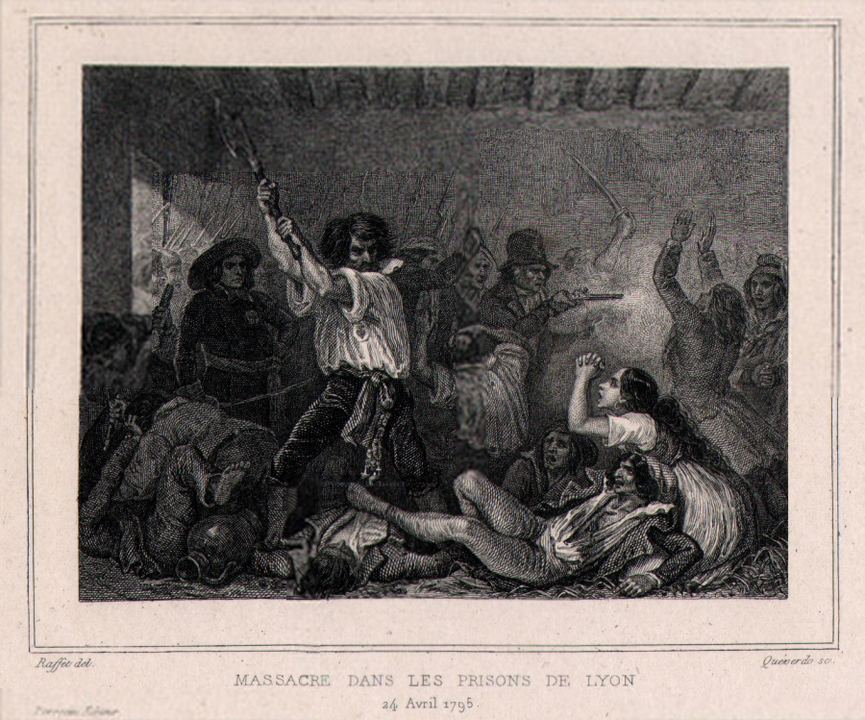

The Companies of Jehu (or of Jesus) and of the Sun hunted down and massacred anyone who fell into their hands: Jacobins, republicans, former administrators, soldiers idling in the streets, relatives of soldiers at the front, without distinction of age or gender, constitutional priests, and Protestants (for socio-economic and political reasons as much as religious ones). Victims were sometimes attacked in their homes, in front of their families, or in the streets, or even in prisons.

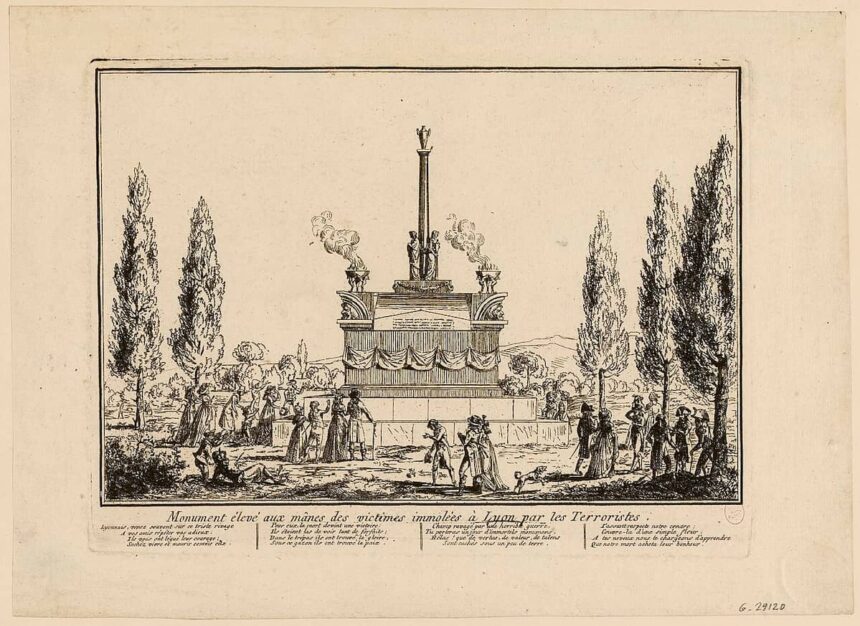

In Lons-le-Saunier, Bourg, Lyon (where around a hundred suspects were reportedly slaughtered in the city’s jails), Roanne, Saint-Étienne, Aix, Marseille, Toulon, Arles (where both sides accused each other of atrocities), Eyragues, Montélimar, Beaucaire (where large amounts of sulfur were thrown into dungeons to try to burn prisoners alive), Tarascon, l’Isle, and Salon (where locals intervened to prevent an attempt on the prison), the violence was brutal and unchecked.

Municipal and departmental authorities, infiltrated by former émigrés, often acted as accomplices to these actions, as did representatives on mission (such as Chambon, who ordered the arrest of all suspects, hypocritically placing them under the protection of the law, then released arrested murderers and armed members of the Company of the Sun). No longer content with merely sawing down Liberty Trees, most victims bore the marks of multiple wounds from firearms, blades, or clubs, showing the determination of their killers.

Other bands were denounced, including the “Triqueurs,” the “Vibou,” or a group of Chouan national guardsmen in the Gard, who united noble émigrés and popular elements. Using denunciation lists, these groups attacked former administrative agents and correspondents of popular societies. The coordination center for these bands was in Lyon.

Considering that prosecutions against the perpetrators of massacres were nearly nonexistent and that identifying victims was difficult, it is estimated that 3% of the perpetrators were nobles, 14% were notables and village mayors, 12% were merchants and members of liberal professions, and 44% were artisans and shopkeepers. Peasants played an important role in the atrocities committed along the roads, with some transforming into highway robbers under the guise of political unrest.

On the other hand, the victims mainly came from the popular classes—artisans and laborers in Tarascon, sans-culottes from Marseille, and workers from the Toulon arsenal, who paid the price for their revolutionary engagement. 42% of the victims were soldiers, gendarmes, volunteers, or conscripts, 34% were former administrators and Jacobin officials, and 12% were constitutional priests, such as the parish priest of Barbentane, who was thrown into the Durance River, bound hand and foot.

It is important to emphasize that this white terror, unlike the Jacobin terror, was not institutionalized. It operated outside any legal framework, without recourse to a tribunal, without the apparatus of justice, and outside the law. Those who claimed to be restoring order began by taking justice into their own hands, thus disregarding any authority, even though they claimed to be fighting for legitimate authority—a frequent contradiction in troubled times. Finally, justice was powerless to punish the guilty because witnesses were either complicit or paralyzed by fear and claimed they had seen or heard nothing.

Although this First White Terror primarily raged in the Rhône Valley and southern France, this was no coincidence. In addition to social antagonisms (the struggle of the canuts against the silk merchants in Lyon), religious quarrels fueled political opposition. The memory of the repression of royalist and federalist uprisings and the proximity of the border, which facilitated infiltrations, also explain the concentration of this disordered outbreak of violence.

The collapse of the Jacobin power structures and the weakness of the Thermidorian authorities left ample room for the Revolution’s most determined opponents. Alongside local supporters of the royalist cause—muscadins, refractory clergy, and relatives of those executed since 1793—the bulk of the royalist forces in Lyon consisted of nobles, priests, or adventurers from outside the city, refugees or clandestine arrivals from abroad. Most notably, the insurrectionary days in Paris during Germinal and Prairial had sparked fears of a Jacobin resurgence.

When the sans-culottes of Toulon revolted at the end of Floréal, perhaps manipulated by royalist provocateurs, and marched on Marseille to free detained patriots, fear gripped the moderates, who feared a repeat of the September 1792 massacres. They organized a preventive counter-revolution. Unable to calm the tensions, the people’s representative in Toulon, Brunet, shot himself, while in Aix, another representative, Isnard, a former Girondin orator, urged his audience to dig up their fathers’ bones to use as clubs to strike down the Jacobins. Isnard even authorized the creation of a Company of the Sun in Brignoles!

The First White Terror in Provence

In Beausset, the disarmed sans-culottes from Toulon were attacked, slashed, and gunned down by Isnard’s soldiers. The prisoners, taken to Marseille, were exterminated—either after being sentenced or spontaneously by a furious crowd storming Fort Saint-Jean, which served as a prison. Some prisoners, already starving, were reportedly killed by the fumes of burning sulfur and straw lit outside their windows. Cannon blasts broke down the cell doors, and others were set on fire where prisoners had barricaded themselves. To complete their horrific task, the executioners did not hesitate to rob these unfortunate souls of their belongings, both before and after killing them, with the active complicity of the fort’s commander, named Pagez!

The number of victims of these counter-revolutionary orgies, in which watchmakers and jewelers drunk on brandy participated under the leadership of the son of a tavern owner named Robin (a sort of reverse “September Massacres”), is estimated at 200, possibly even 600, including several women. The report noted that most of the dead were so disfigured they were impossible to identify! Several military depositions condemned the behavior of the people’s representative, Cadroy (from Le Véridique newspaper), who not only protected the assassins but even encouraged them. Graves with quicklime had been prepared at Marseille’s lazaret to bury the bodies several days before the massacre, and no food was prepared for the prisoners the next day, proving the massacre was premeditated.

Marseille was, unfortunately, not the only place where prisons were stormed. In Aix, on 23 Floréal, Year III (May 12, 1795), according to the municipality, around thirty prisoners perished under the attackers’ blades. In Tarascon, on 6 Prairial (May 25, 1795), 24 prisoners, mostly artisans and a former canon, met the same fate, reportedly thrown from the castle towers into the Rhône River or onto the rocks that shredded them.

Again in Tarascon, on 2 Messidor (June 20, 1795), the agitated crowd repeated their actions: 23 more individuals, including two women, were thrown out of windows at around 3 a.m. On the night of 2 to 3 Messidor, the fort of Eyragues also received grim visitors, leaving behind an unknown number of corpses. In Roanne, 94 prisoners, including three women, were massacred by about twenty men, likely from Lyon. As the prisoners defended themselves and even killed some of their assailants, the attackers set fire to the prison.

Armed insurrections, following the spirit of the Paris sections’ uprising on 13 Vendémiaire, supported these chaotic crowd movements. One such uprising occurred in the Drôme, led by a certain Job Aimé and the Marquis de Lestang. Their army failed to capture Avignon’s castle, where they allegedly intended to slaughter prisoners, and also failed at Montélimar. Eventually, troops recalled from the Italian army dispersed them. However, similar movements were stirring nearby regions, notably in Ardèche, Gard, and Lozère. An assault was even attempted on the Saint-Etienne arms factory. The suppression of the Parisian sections’ uprising calmed these military uprisings but did not stop the atrocities.

Aside from political crimes, many of the massacres were also driven by greed, revenge against members of certain communities, or old regional rivalries, often targeting Protestants or those who had acquired national property. Authorities, threatened by the violent fervor of opposing religious groups, sometimes redirected the violence onto former terrorists. These acts ranged from threats and insults to arbitrary arrests without warrants, murders of prisoners, personal attacks, looting, imprisonments, and individual executions (notably by stoning).

It’s difficult to ascertain the exact number of victims; not all were detained, and the number of prison murders was likely downplayed by administrators fearing Paris’s disapproval. Depending on the sources, Aix saw around sixty killed, Tarascon between 47 and 60, and between Orange and Pont-Saint-Esprit, during a prisoner transfer, 55 (or 14). The total number of lives lost during these days is estimated to be in the thousands, possibly ranging from 2,000 to 30,000!

These barbaric acts were witnessed by numerous spectators, much like the guillotine executions, following the long tradition of public shaming rituals like charivaris or farandoles. In Vaucluse, a convict exposed in the pillory was reportedly torn apart by the crowd, while another was allegedly buried alive. In Sisteron, Breyssand, a district administrator wrongly arrested and freed by the Committee of General Security, was re-arrested while hiding with his parents to escape his enemies’ wrath. He was assaulted with stones and sabers, left for dead, revived by his former constituents, only to be killed on his hospital bed, dragged through the streets, and dismembered on the banks of the Durance!

Of the 415 murders committed between Year III and Year V (1795-1797) in the Bouches-du-Rhône, Vaucluse, Var, and Basses-Alpes, 66% occurred in just three months, from Floréal to Messidor, Year III (April-June 1795). After the Jacobin uprising in Toulon on 28 Floréal and the Parisian insurrection on 1 Prairial, the killings reached their peak in Prairial, with 50% of the massacres taking place in Provence. From Haute-Loire to Bouches-du-Rhône, the killers hunted down Republicans, often identified by a justice of the peace or an innkeeper. Every day and night, Jacobins were assaulted, injured, and thrown into the Rhône.

The First White Terror in Lyon

In Lyon, the White Terror continued with a wave of violence, collective assassinations of former revolutionary leaders from Lyon, and the elimination of informers following the publication of the General List of Informers and the Denounced in February 1795. This lasted until the city was placed under siege in February 1798. In Saint-Étienne, after the release of numerous suspects, including local notables, and successive purges of the town hall and the departmental directory—which saw the arrival, between December 1794 and January 1796, of individuals compromised in royalist subversion—a hunt for Jacobins began in March 1795.

On March 12 and 13, 1797, muscadins (royalist supporters) armed to the teeth, spread terror through the streets of the city. They forcefully entered the Verrier tavern, a gathering place for Jacobins, killed three people, fatally wounded a municipal officer, Mory, and nearly killed another. On January 1, 1798 (12 Nivôse Year VI), the mayor, Jean-Baptiste Bonnaud, was struck in the head by two individuals at around 8 p.m., two days after sending the police to search the house of a businessman, Jovin, where a refractory priest had set up a clandestine chapel. The government eventually placed the city under siege on March 28, 1798, until April 22, 1800.

To end the abuses, the Convention sent Fréron back to the south. He returned with an anti-royalist report, which was published but should be read with caution, especially since he was suspected of embezzling public funds for personal gain, and his drastic shifts in allegiance left many perplexed. His opponents, including Isnard, accused him of resurrecting the Jacobin terror against federalists and royalists.

The Convention, in its final days, hardened its stance.

Several Jacobin generals who had been sidelined were recalled, including Rossignol and especially Bonaparte. Before dissolving to make way for the Directory, the revolutionary assembly had to overcome a royalist insurrection by several Parisian sections. Barras, who commanded the republican forces, relied on Bonaparte, who fired cannons—brought from the Sablons camp—on the insurgents on the steps of the Saint-Roch church in Vendémiaire Year III (October 1795). Afterward, the Directory was marked by a series of coups, with power, fragile and constantly under threat, alternating between striking the right and the left, targeting royalists first and then Jacobins.

During the Fructidor coup, the Directory triumphed once again thanks to Bonaparte’s intervention. He sent General Augereau to rid them of the royalists, who were deported to Guyana. However, the Directory eventually fell on 18 Brumaire (November 1799) under the blows of the same Bonaparte. Bonaparte finally pacified France, putting an end to the unrest that had continued to plague the country, which had mostly descended into mere banditry. Upon his return from Egypt, a few probable heirs of the First White Terror robbed the Mamluk Roustan, who believed he had been attacked by French Arabs. But the final embers of this turmoil were soon extinguished by the firm hand of the First Consul…