In the Middle Ages, the imaginary is an integral part of reality. The world of that time cannot be conceived otherwise. Within this panorama, both real and wonderful, plants play a major role in various domains. Whether from a political, heraldic, literary, or material perspective, the plant world is everywhere. Often, as is common almost everywhere in the Middle Ages, the Scriptures justify certain choices and give meaning to the staging of particular flowers, plants, or vegetative structures.

First, we will focus on the literary domain with the case of the honeysuckle in the poetry of Marie de France. Subsequently, with the example of medieval gardens, we will explore how correspondences are woven between the material world and the imagination of the people of that time. Then, we will examine the fleur-de-lis, viewed more from a “political” angle, to clarify the myths surrounding it. We will conclude with a brief symbolic history of the apple.

Natural Symbolism in Marie de France: Honeysuckle and Hazel

Among the works attributed to Marie de France, a 12th-century poet, there is a collection of twelve brief stories written in octosyllabic verse, the Lais. These stories, which are relatively short in length, are imbued with assured love and eroticism. In the 12th century—the period of composition of these “poems”—fin’amor was flourishing. However, this carnal passion was not accessible to everyone. It was the privilege of noble people, of the Lady and her lover. The erotic symbolism of the lais is embodied in various elements, some of which are quite material. Nature can also play the role of awakening and revealing the senses. Fauna is particularly favored, especially birds, which are much appreciated by the poetess. Additionally, flora is well-represented, which is what interests us here.

To describe the union of lovers, Marie de France uses the famous and evocative image of the honeysuckle entwining the branch of the hazel tree. This theme already appears in various mythologies, such as in Celtic tradition. This vegetal metaphor is actually used to courteously illustrate the union of Tristan and Iseult. However, the embrace of the two lovers should not be perceived as purely carnal. As mentioned, Marie de France’s poetry is part of the fin’amor tradition, where courtly values are paramount. The honeysuckle conveys an image of purity and freshness, perfectly aligning with the sentiment the poetess wishes to evoke in the reader.

While the honeysuckle itself carries a strong symbolic charge, the hazel tree—and more broadly, the surrounding trees—give the story an ambiance conducive to the flourishing of romantic feelings. Both attractive and unsettling, the forest is a space where sensuality can bloom. Hidden behind the branches, the two lovers experience a privileged moment. It is also thanks to the wood that Tristan is recognized by his beloved. On a hazel branch, he carves his name, allowing Iseult to follow his trace.

The image of the honeysuckle entwining the hazel branch is also an evocation of absolute and infinite love. Indeed, as Marie de France clearly states, once separated, the two plants die shortly afterward. The honeysuckle and hazel form an inseparable couple, just like Tristan and Iseult. Should separation occur, the outcome will be tragic. This is encapsulated in Marie de France’s beautiful concluding phrase in the lai: “Neither you without me, nor I without you.”

The use of plant imagery here invokes both purity and freshness, where the erotic tension is thereby intensified. It is this interplay of dualities that gives the poetess’s lai its full flavor.

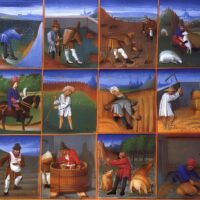

Reality and Imagination in Medieval Gardens

From the 11th to the 13th century, the population of the West grew significantly, leading to an increasing demand for gardens. Consequently, the medieval lexicon is rich in terms used to describe these types of spaces, sometimes described from a utilitarian perspective, other times staged in literature infused with Christian or secular culture. Generally, the courtil refers to the small plot of land adjacent to the house where some vegetables are grown for local consumption.

From the 13th century, the term casal appears in the southwest to describe a similar type of space. Alongside these utilitarian gardens, the pourpris is more present in literature. It typically refers to a plot enclosed by a wooden fence or thorny bushes (hawthorn, rosebush…). Similarly, the jarz or vergier are places of tranquility where lovers meet among flowering trees, preferably in May.

Contrary to what one might think, gardens are not only found in rural areas. Indeed, until at least the 12th century, the urban fabric remained sparse enough to accommodate numerous gardens, vineyards, meadows, or barns. Even in the second half of the 13th century, large urban centers still had many such spaces. Toponymy has preserved traces of this, as evidenced by the street names in Paris: Rue des Rosiers, Rue des Jardins, Rue du Figuier…

In 14th-century Reims, there were still about 46 urban gardens. As housing density increased and construction took over undeveloped land, gardens were pushed to the periphery while still remaining within the city walls. Cities were also surrounded by a “gardening halo.” These gardens supplied the city with vegetables, fruits, wine, and other roots or medicinal plants. In any case, in the city, owning a garden could be considered a sign of wealth. Aristocratic, knightly, and soon-to-be merchant families used this element to assert their social preeminence. Louis IX himself owned a vergier on the tip of the Île de la Cité.

The design of a garden was thought out based on the role it would serve. In general, care was taken to enclose it to prevent animal—and sometimes human—intrusions. Fruit and vegetable thefts were common and sometimes led villages into long-lasting disputes. To prevent this, one could use branches, hedges, stone, or bricks when the means allowed.

Beyond the purely utilitarian function, the enclosure also became a marker of a spiritual space that invited meditation. The enclosed garden then directly referenced those in the Scriptures. A prefiguration of Paradise on earth, it became the place where the divide between savagery and civilization took shape. Similarly, many jarz and vergiers featured fountains. Beyond the obvious utilitarian aspect, the clear and pure water flowing through them resembled the four rivers irrigating Paradise.

The flora of ornamental gardens was varied. Flowers were highly prized and sought after. Here, too, the symbolism of plants played a major role, as seen in the Roman de la Rose… In fact, rose cultivation was widespread in the Middle Ages. The red rose and its bud were enough to evoke love and eroticism. Alongside, one often found wild roses, gladiolus, lilies, daisies, and other wildflowers. In addition to offering a bit of shade and precious fruits, trees were cultivated with particular care.

There was also a great variety of species: service tree, cherry, chestnut, fig, pomegranate… Non-fruit trees like ebony, laurel, plane tree, or pine also composed the landscape of these medieval gardens. The same applied to aromatic or medicinal plants. Ultimately, a good ornamental garden was one that appealed to all the senses: the bright colors of the flowers; the varied scents of herbs; the softness of petals against the rough bark of trees; the enchanting sound of branches swaying, sheltering lovers hidden behind a thick flowering bush.

The Power of Flowers: The Lily

There are many myths and legends surrounding the fleur-de-lis. However, it is an authentic historical object connected to various fields, including politics, dynasties, art, emblems, and symbolism. This stylized figure can already be found on Mesopotamian cylinder seals or engraved on Egyptian bas-reliefs. It even appears in Japan as well as on Sassanid fabrics. The oldest depictions of the flower, resembling those known in medieval Western Europe, date back to the 3rd millennium BCE in Assyria. Of course, its meaning changes with each period and in each region. Nevertheless, the lily almost everywhere maintains connections with power.

The Middle Ages endowed the fleur-de-lis with a threefold religious dimension. First, it became a Christological symbol, based on the Scriptures, particularly this passage: “I am the flower of the field, and the lily of the valleys” [Song of Solomon 2:1]. With the development of Marian worship in the 13th century, the lily became a marker of purity and virginity, once again referencing the Scriptures: “Like a lily among the thorns is my darling among the maidens.” [Song of Solomon 2:2]. Medieval iconography frequently associates the Virgin Mary—and more broadly, noble ladies—with the lily. Finally, the evocative shape of the flower allowed theologians to make it an allegory of the Trinity and associate it with the three essential virtues: Faith, Wisdom, and Chivalry.

The lily is also associated with power, as mentioned earlier. From the 14th century, chroniclers enjoyed telling that Clovis himself was the first king to adopt it. However, the Merovingian’s choice of the fleur-de-lis is purely a medieval invention. The first serious material evidence of a direct link between the flower and royalty dates to 1211, with the seal of Prince Louis, the future Louis VIII. However, under the influence of figures like Suger or Saint Bernard, the Capetians, at least since Louis VII, seem to have used the lily as a sign of their piety, without yet making it a royal attribute.

The arms of azure scattered with golden fleur-de-lis are definitively attested around 1215, thanks to a stained glass window in the cathedral of Chartres. However, it is plausible that from the reign of Philip Augustus (1180-1223), the lily had already been incorporated into the royal arms. Thus, by using the floral emblem, the Capetian monarchy placed itself directly under the protection of the Virgin Mary. The king became the mediator between Heaven and Earth.

With its new coat of arms, the king of France distinguished himself from other sovereigns in several ways. While England favored the leopard, the Empire the eagle, or Castile the castle, the Capetian was the only one to use a floral emblem. Similarly, he was the only one to use a scattered pattern (semé). The cosmic dimension was undeniable and was reinforced by the choice of colors—blue and yellow—which directly evoked the starry sky. From 1372, the scattered lilies were replaced by three fleur-de-lis. This time, it was not the Virgin who watched over the monarchy but “the blessed Trinity.”

In general, from the 11th to the 15th century, the French monarchy maintained close ties with the plant world. Consider the lily, of course, but also the flowering rod, the scepter, and the flowered crown. Similarly, Valois princes and kings drew heavily on floral emblems: roses, daisies, irises, holly, currants… We can also add the famous oak of Saint Louis, of which Joinville enjoyed recounting that it “often happened in the summer [that the king] would go to sit in the woods of Vincennes after mass, lean against an oak, and have us sit around him.”

However, the use of the fleur-de-lis was by no means a royal monopoly. Elsewhere, it functioned as a heraldic emblem in its own right. It is mainly found in the arms of the lesser and middle nobility of northern Europe, or even in Italy. Similarly, in some regions like Normandy, many peasants engraved a lily on their seals. Here, it was a common figure with no apparent direct link to its power symbolism.

In rural areas, it was more associated with the plant world and fertility than with the monarchy. Cities like Lille or Florence even adopted the lily as their main emblem within their coats of arms. In both cases, the flower played a “speaking” role through the Latin terms lilium and flor. Finally, many abbeys or cathedral chapters used the lily, which then took on its full religious dimension. Ultimately, the fleur-de-lis in the Middle Ages had different uses and carried multiple symbols depending on the context in which it was found.

In medieval culture, the apple frequently relates to theft on one hand and pleasure on the other. In the West, it became the quintessential fruit, while this role was occupied by the pomegranate in Islamic civilization or the plum in Japan. In Latin, the term pomum was used to refer to fruits in general. We still find traces of this today: pomme de terre (potato), pomme de pin (pinecone), pomme d’or (golden apple)… The word pomum evokes the idea of roundness. A distinction was then made between fleshy fruits (malum) and those with shells (nux). In summary, the apple is first referred to as pomum and then as malum.

Since antiquity, the apple has often been associated with the walnut when depicting the plant world. In the medieval period, a new pairing emerged: the apple and the pear. These two fruits love and compete with each other simultaneously. The pear’s curved shape and soft texture made it resemble a woman, while the apple played the masculine role. Numerous proverbs depicted the two fruits. In the 13th century, it was said that “there is no worse pear than an apple,” or that “an apple given is better than a pear eaten.”

Mythology has long had a close relationship with the apple, dating back to antiquity (see The Judgment of Paris). Think of Avalon, described as the insula pomorum by Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 12th century. On this mythical island where heroes and illustrious kings rest, King Arthur awaits his messianic return. Everything grows naturally around him, and the place is guarded by the fairy Morgan le Fay. To attract certain travelers and grant them immortality, Morgan and her fairies waved apple branches. As often, the apple served as a connection between the world of the gods and that of men. Similarly, many mythical stories depicted this fruit as one capable of bestowing immortality.

The apple also entered the realm of power. Since the late Roman Empire, the scepter, crown, and spherical globe were the typical attributes of royal or imperial power. In the Middle Ages, Byzantine and German emperors, and some kings, retained the globe. It was not uncommon for it to be compared to a real apple, both in texts and in iconography. For example, at the end of the 12th century, the orb of the Holy Roman Empire was called the Reichsapfel, or “apple of the Empire.” In this case, the use of our fruit symbolized the prosperity and abundance guaranteed by the emperor.

It was also in the Middle Ages that the tree of knowledge (Genesis 2:16-17) took the form of an apple tree through a clever process. Indeed, in Latin, the word for apple and the word for evil are the same, malum. Medieval culture liked to link words and things. Furthermore, the apple tree as a symbol of knowledge could also find its roots in other mythologies—such as among the Celts—or in the Arthurian cycle. For example, it is under an apple tree that Merlin tests his knowledge when practicing magic.

In addition to these positive aspects, the apple was also viewed with suspicion and intrigue. The theme of the poisoned apple is already attested at the beginning of the 13th century in Le Morte d’Arthur (The Death of Arthur). Guinevere was accused of offering our venom-soaked fruit to Gaheris the White. Similarly, the apple could be associated with the Devil’s abode. At certain times, it could harbor creatures reviled by medieval culture—worms. These vile insects were believed to be born from decaying flesh. Moreover, the Scriptures remind us that “for the punishment of the ungodly is fire and worms” [Sirach 7:17-19]. A final negative aspect, which would deserve an entire article, is the connection between the apple and woman. The evil couple par excellence, it is the symbol of the Fall caused by Eve plucking the forbidden fruit.

Ultimately, the apple is one of the most prevalent fruits in both scholarly and popular culture of the Middle Ages. Taken in a positive light, it could bestow immortality, and blossoming apple trees were considered the most beautiful trees. Taken negatively, the apple became malevolent and dangerous, symbolizing female corruption and evil.