Pope Innocent III, in 1198, disregarded the agreements between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin and called for a Fourth Crusade to retake Jerusalem. However, this time, he was not supported by the major European monarchs, and it was the barons who responded to the call and sought help from the powerful Venice. The consequences were not suffered by the infidels but by the “Second Rome”: Constantinople!

Byzantium and the Latins

Tensions between the Byzantines and the Crusaders had hardly ceased since the First Crusade, and various Byzantine emperors always sought to maintain influence over events in the Holy Land, at times acting against the Latins. But the Empire had been in crisis since the 1180s, following the death of Manuel Komnenos. In 1182, a coup brought Andronikos Komnenos to power at the expense of Alexios II, the legitimate heir; at that time, the people of Constantinople, galvanized by Andronikos’ men, massacred the Latins in the city!

The antagonism between Greeks and Latins was twofold: religious since the Schism of 1054, and economic with the rise of Italian cities threatening Byzantium’s hegemony in the eastern Mediterranean. There was also a political dispute, heightened in the following years by the passage of Frederick Barbarossa during the Third Crusade, which directly confronted Byzantine armies, as Isaac II had allied with Saladin.

The Byzantine Empire was under internal strain, but also external threats, with an ever-present Bulgarian menace, not to mention the Turks. This benefited Alexios III, who overthrew Isaac II. On the eve of the Fourth Crusade, imperial power was still far from stabilized.

Venice at the End of the 12th Century

The rise of the famous Italian city occurred in the context of wars with the Holy Roman Empire under Frederick I and the creation of the commune system. Venice had maintained privileged relations with Constantinople since agreements dating back to the late 11th century, allowing it to surpass its Italian competitors in the eastern Mediterranean.

In 1183, the Peace of Constance temporarily settled the conflict between the German Emperor and the Italian cities, giving Venice (and its rivals) the freedom to continue their economic development independently. The death of Frederick I, and soon after that of Henry VI, did not change the situation as their successor, Frederick II, focused on southern Italy and Sicily.

Venice was thus in a strong position when the Crusaders sought a fleet to transport them to the Holy Land.

Departure of the Fourth Crusade

The pope, like his predecessors, sought to use the Crusade to unite powers under his authority amidst the ongoing Franco-English war, not to mention the more immediate dangers in the Italian peninsula. However, he could only recruit barons, despite his attempt to mediate between Philip Augustus and Richard the Lionheart through the legate Pietro Capuano.

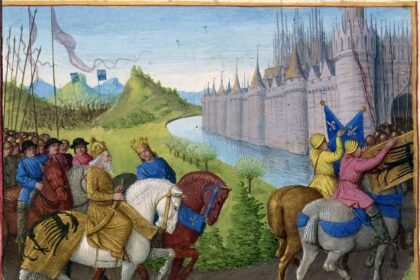

Fulk of Neuilly was tasked with preaching the Crusade from late 1198, but it wasn’t until the end of 1199, at the tournament of Écry, that the Crusade truly took shape. It was to be led by the Count of Champagne, Thibaut (who died in 1201 and was replaced by Boniface of Montferrat), and the elite knights from northern France, including Louis of Blois and Simon de Montfort. The Crusaders then asked the Italian cities to transport them, but Genoa and Pisa refused, leaving only Venice. Agreements were made for transportation and the sharing of any conquests.

It was decided to gather in 1202 in Venice and then head directly to Egypt. The situation with Byzantium had become more strained than ever, making the usual route through Constantinople less safe.

Diverted Crusade: The Siege of Zara

The Crusader army assembled in Venice was smaller than expected. The problem was that the Venetians had prepared to transport 30,000 men and were determined to be paid for that. Eventually, 34,000 marks were missing from the 85,000 demanded by Venice. Doge Enrico Dandolo then offered the Crusaders a moratorium on their debt if they helped him capture Zara, in Dalmatia. The issue was that the city, although rebellious, was Christian, and the pope immediately warned that he would not tolerate a Christian city being attacked by soldiers of Christ!

The Venetians and Crusaders ignored this warning, and Zara was besieged in November 1202. Its inhabitants hung crosses on the walls to signify they were Catholics, tried negotiations, and tensions grew among the Crusaders. But under the insistence of the Doge, the assault was launched on November 24! The city was pillaged, the Crusaders settled there, but Innocent III only excommunicated the Venetians…

Crusaders “Liberate” Constantinople!

Indeed, during the siege, negotiations brought in other key players. It seems that Philip of Swabia, contacted by Crusader Boniface, reached out to his brother-in-law, Alexios, the son of Byzantine Emperor Isaac II, who had been deposed and blinded by Alexios III in 1195. The young man had escaped from prison and, through Philip’s intervention, met with Boniface in Zara, asking for help against the usurper Alexios III.

The terms of the agreement included the promise of uniting the two Churches, but in Rome, Innocent III did not seem to approve of this deal. Negotiations continued, and Philip of Swabia managed to secure the Crusaders’ support by promising large sums of money from Alexios IV. Despite disagreements among the barons, the agreement was approved, even by the Venetian Doge, and the young Byzantine prince joined the Crusaders in Corfu in April 1203. The pope did not intervene, not wanting to break the momentum of the Crusade.

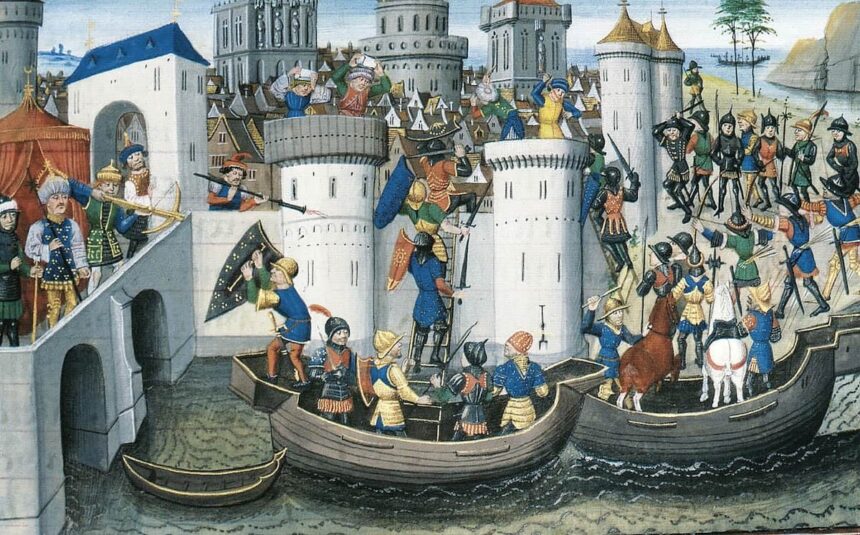

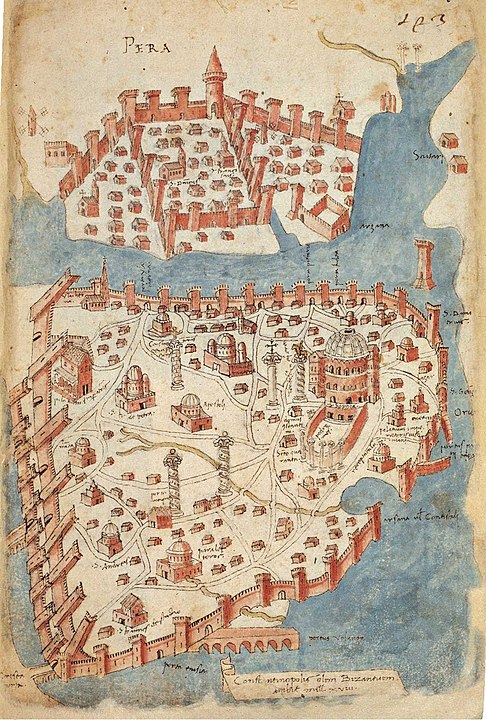

The Crusaders did not forget to destroy Zara before leaving, and then set out for Constantinople, which they reached a month later. However, contrary to what Alexios IV had promised, the Byzantines did not welcome them as liberators from Alexios III’s yoke! A siege became necessary. On July 6, the capture of Galata allowed the Crusader fleet to advance into the gulf, but it wasn’t until July 17 that the usurper fled the city, defeated. The legitimate emperor, Isaac II, was restored but was forced to ratify his son’s promises, with Alexios IV crowned co-emperor on August 1.

Crime Against Constantinople

Soon after, difficulties arose. The Empire was no longer what it once was, and the emperors proved unable to fulfill their promises, financially or religiously. The Crusaders also distrusted Isaac II, who had once allied with Saladin, and relations between Greeks and Latins in the city were atrocious. An “anti-Latin” party emerged in Constantinople, led by Alexios Murzuphlos (also known as Alexios Doukas), the son-in-law of Alexios III. On January 29, 1204, he imprisoned and strangled Alexios IV, which Isaac II did not survive for long! Alexios Doukas crowned himself emperor as Alexios V.

Naturally, the Crusaders viewed the rise of someone who roused the populace against them with suspicion, especially as he likely had no intention of repaying the debts of his predecessors.

Additionally, they were still indebted to Venice, which was growing impatient, and the Crusade was stalling. The barons and the Doge signed new agreements to share the spoils after the capture of the city, which took place on April 13, 1204, after several days of fierce fighting.

The city was mercilessly pillaged for three days, even within the walls of Hagia Sophia, where precious stones were torn from the altar. The patriarch’s throne was desecrated by a prostitute, as were the tombs of the emperors, which were opened and their bodies stripped! The rest of the city was also devastated, and the Venetians even took the quadriga statue, now on the façade of St. Mark’s Basilica.

Division of the Empire and the End of the Fourth Crusade

One might remark that this was a curious way to lead a crusade, but it is difficult to easily designate the culprits. The chain of circumstances was fatal, but we can also point to the ambitions of certain individuals, such as Boniface of Montferrat, or the diplomatic maneuvers of the Hohenstaufen, through Philip of Swabia, to weaken the Empire and thus facilitate their projects in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean.

Finally, of course, the ambitions of Venice cannot be overlooked. However, it seems that the majority of the crusaders were against diverting the crusade, whether towards Zara or Constantinople (it is even said that some of them went to Palestine before heading to Venice!). Then, the need for unity within the crusader army and the actual chain of events, such as the crimes of Alexios V, could hardly lead anywhere other than disaster. But this mainly confirms the difficulties seen since the First Crusade between the Byzantines and Latins, and the inevitable competition for hegemony in the region. Beyond that, the rivalry between the two Churches did not help, and, of course, the capture of Constantinople definitively shattered any hope of reconciliation, as the resentments still linger to this day.

With the capital under Latin control, the empire itself was divided among the victors: this is the “Partitio Romaniae.” A Latin Empire of the East emerged from the ashes of Constantinople, and Baldwin VI of Hainaut was installed as emperor by the Venetians, to the detriment of Boniface of Montferrat, who would go on to found the Kingdom of Thessalonica. Venice seized most of the islands, and one of its own, Marco Sanudo, founded the Duchy of Naxos.

However, the Byzantines were not completely defeated: several princes established other kingdoms, the most notable being the Empire of Trebizond, ruled by the Komnenos family (which would last until 1461), and especially the Empire of Nicaea, ruled by Theodore I Laskaris. It was one of his successors, Michael Palaiologos, who managed in 1261 to retake Constantinople and restore the Byzantine Empire with the support of Genoa.

In the meantime, what became of the crusade?

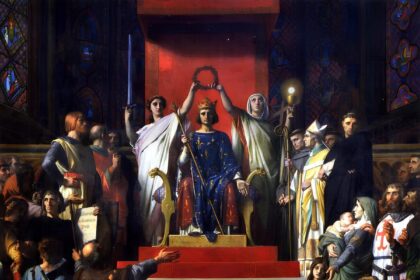

The Latin clergy took advantage of their “opportunity” to seize the numerous relics that were kept in Constantinople and brought them back to the West. It seems that this was enough, as there was no further mention of the crusade ordered by Innocent III. Subsequently, it was primarily monarchs who took the initiative for crusades, including Saint Louis but first Frederick II, despite a final attempt by Innocent III.