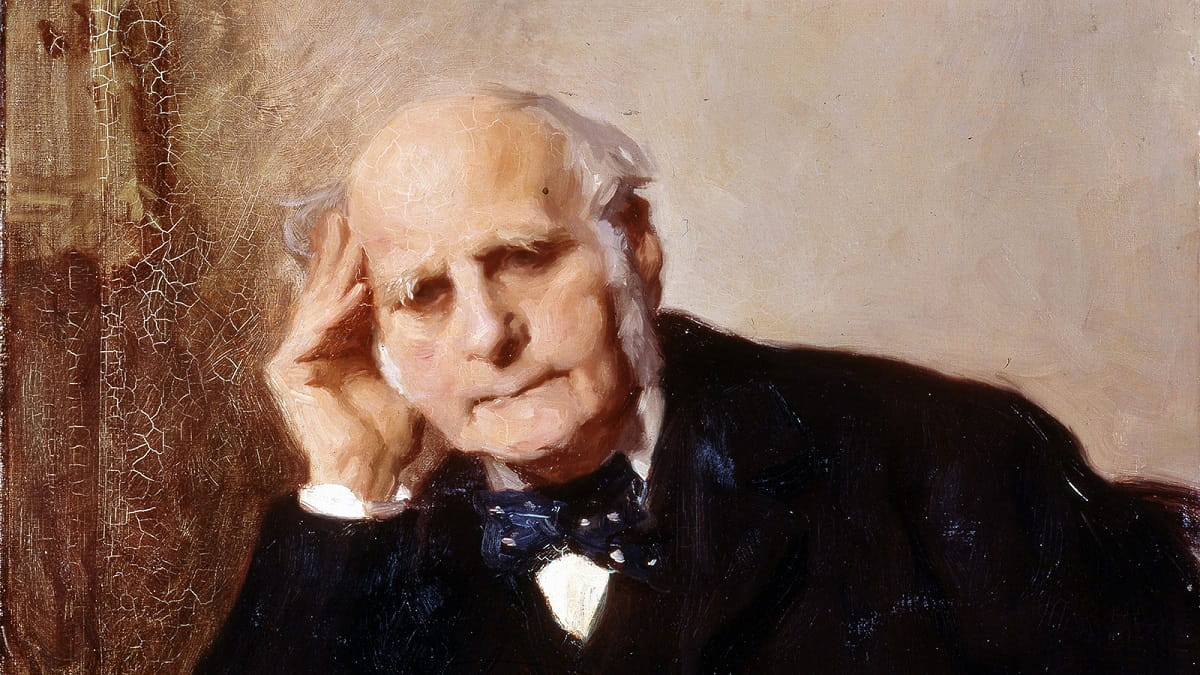

Often known as the father of the eugenic movement, Francis Galton was interested in a wide variety of fields, from the exploration of Africa to psychology, statistics, and fingerprint control. Tertius and Violetta were the youngest of Galton’s nine children. He was related to his older cousin, Charles Darwin, through their grandfather, Erasmus Darwin.

Francis Galton’s early life

It was taken for granted that Francis Galton, like Darwin, would study medicine. He started his education at the fully-fledged hospital in Birmingham, but in 1839 he transferred to King’s College in London. He had just returned from his Beagle cruise and was living near Darwin, who had just married Emma. Having hated his medical experience in Edinburgh, Darwin persuaded Galton to drop his medical education and join his university, Cambridge. In October 1840, Galton went to Trinity College, hoping that he would graduate with honors in mathematics, but he graduated only with an average degree.

After drifting aimlessly for six years, Francis Galton organized an expedition to uncharted parts of Namibia, discovering a new tribe, the Ovambos, and taking meticulous measurements of the latitude, longitude, and temperature of the area. When he returned to England in early 1852, he was awarded the Founder’s Medal by the Royal Geographical Society. In 1853, he married Louisa Butler, the daughter of George Butler, Dean of Peterborough Cathedral, and published his first book, Tropical South Africa.

Two years later, he published a very successful guidebook called The Art of Travel. However, he became interested in making retrospective weather maps, during which time he discovered high-pressure systems where the wind moved clockwise. These various steps formed the first part of Galton’s career.

The idea of hereditary talent

The second phase began with Darwin’s publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859. Darwin used examples of artificial selection, such as fancy pigeons, to show how natural selection might work. Francis Galton thought that if selection works for pigeons, it can work for humans as well. Maybe the human race could also be developed by selective breeding.

In 1865, Francis Galton’s article titled “Hereditary Talent and Character” was published in MacMillan’s Magazine, one of the many high-quality periodicals of the Victorian era. In this article, he examines the close relatives of famous people in his ensuing 1869 book, The Hereditary Genius. If talent and character are hereditary, he thought, these elite individuals’ closer relatives might have been more distinguished than their distant relatives. Galton came to the conclusion that this was, in fact, the case, ignoring bias and wrongdoing. That is, a famous man could get his son a job.

The Hereditary Genius is regarded as the first example of the historical study of human progression or individual traits. Also in this context, Francis Galton is the first person to ask the question, “nature or nurture?” He even worked on a questionnaire and sent it to 190 people from the Royal Society to justify this issue with solid evidence. He tabulated the characteristics of these individuals’ families and tried to find out whether their interest in science was “innate” or came with the support of others. These studies were published in Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture in 1874.

Acquired properties

In 1875, the second edition of Darwin’s book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication was published. It was the chapter titled “The Theory of Pangenesis” that aroused Galton’s curiosity. Darwin needed a source of variation to keep natural selection working. He claimed that the particles he called gemmules were collected from different parts of the body to form sexual elements, and that their development in the next generation creates a new living being.

Darwin thought of two mechanisms that produced variations. The first was that the genitals suffered damage that prevented the gemmules from assembling properly. Second, the gemmules could change due to the direct effect of changing conditions. These altered gemmules are then transferred into offspring, and after many generations, the change becomes inherited.

Francis Galton was very interested in Darwin’s hypothesis, although he disliked the idea of gemmular differentiation with changing environmental conditions. From this, he attempted to form his own theory of inheritance. His theory was a version of the German evolutionary biologist August Weismann’s theory of heredity, which means that acquired traits are not passed on to subsequent generations (Weismann made this point in his 1889 letter to Galton) and that inheritance occurs only through the inheritance cells (egg and sperm cells).

The anthropometric laboratory is established

But Francis Galton was more of a practical scientist than a theorist. In particular, he wanted to analyze data on human characteristics. On the advice of Darwin and botanist Joseph Hooker, he decided to measure the seeds of sweet peas. One reason he chose the sweet pea was that it usually does not cross-fertilize. Galton found that seed sizes were distributed in the next generation similarly to those in the ancestral plants. But he also found that the average seed size of the big ancestral seed returned to the mean. This was true for small seeds. When Galton plotted the mean diameter of the ancestral seeds along the x-axis and the new generation along the y-axis, he got a straight line. It was the first time that he obtained the regression curve, which was now one of the basic principles of statistics. From here, he calculated the first regression (or reversion, as he called it) coefficient.

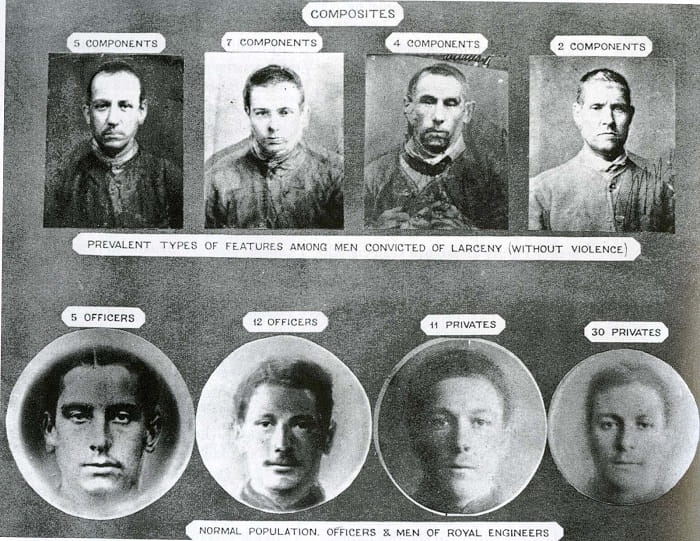

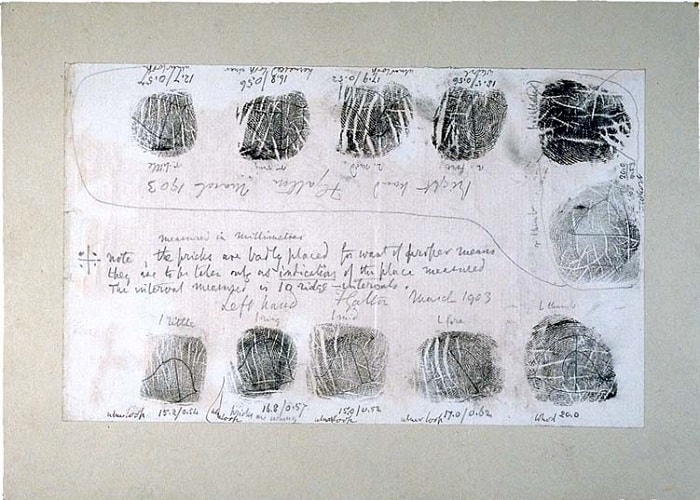

In 1884, Francis Galton London set up an anthropometry lab at the International Health Fair in South Kensington. Visitors were given cards on which various measurements were recorded. Galton also managed to collect partial origin data. From there, he showed that regression to the mean is also valid in humans. He also saw the correlation of measurements when he plotted a measurement such as forearm length on the axis of coordination with height and thus obtained the correlation coefficient, a new milestone in the history of statistics.

When the International Health Exhibition closed in 1895, Galton moved its anthropometric laboratory to the South Galleries of the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria & Albert Museum). Francis Galton was now interested in fingerprints, so he added a place for the thumbprint to his questionnaire. His friend, Sir William Herschel of the Bengal Civil Service, made the key observation that fingerprint patterns remained the same over time. In the 1890s, Galton published two books on fingerprints and played an important role in the use of fingerprints for personal identification.

Heredity and eugenics

Francis Galton’s most important book, “Natural Inheritance,” was published in 1889. This book inspired three main followers: Karl Pearson, W. F. R. Weldon, and William Bateson. The chapters about normal distribution and the continuous variation of characters grabbed the attention of Pearson and Weldon. But there was something else that caught Bateson’s attention. Galton was grappling with a problem. How could natural selection proceed in small marginal steps when it was constantly thwarted by regression and returns to the mean?

To solve that problem, Francis Galton put forward the “organic stability” hypothesis to create variants that cannot return to the mean. According to Bateson, these discontinuous variants were exciting. He compiled many examples of discontinuous variation and published them in 1894 under the title Material for the Study of Evolution. As a result, Bateson was ready to rediscover Gregor Mendel‘s principles in 1900. Mendel’s laws defined the distinction and diversity of the different traits that Bateson was interested in, such as yellow and green pea seeds.

On the contrary, Pearson and Weldon were firm supporters of the new model Francis Galton proposed in 1898, called the Law of Ancestral Heredity. The ancestral law was indeed applicable to the entire genome because it was based on a continuous series in which parents contributed half (0.5), grandparents a quarter (0.5) 2, and great-grandparents one eighth (0.5) 3. When the whole series was added together, it was equal to 1. Pearson and Weldon tried to adapt Galton’s ancestral law to different traits, but every time Bateson failed his attempts by showing that Mendel’s principles were much more in line with the data.

Francis Galton and human intelligence

Francis Galton was also interested in measuring human intelligence. Anthropometry obtained the first estimation from laboratory data. But later, he developed a better idea. He knew that there are two different types of twins, now called identical twins and fraternal twins. He published his findings in Fraser’s Magazine in his 1875 article. He found that identical twins were behaviorally similar beyond their physical similarities. He could not quantitatively measure their intelligence because an IQ test had not yet been created. But their results suggest that behavior and, therefore, intelligence have a distinct inherited component.

Francis Galton described eugenics in a footnote to his 1883 book, Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development. He explained that eugenics deals with questions about those who have superior qualities by inheritance, terminated by the Greek word eugenes, that is, “well-born.” He continued to use eugenics in his speeches and writings, and eugenics gained popularity in the 20th century. But it was not Galton’s idea to favor positive eugenics and weed out inferior eugenics.

The idea began to gain momentum at the First International Congress in London in 1912, a year after Galton’s death. There have been many bad and unexpected results, especially in the United States, Scandinavia, and Nazi Germany, where women who were thought to be mentally or physically unhealthy were forced to get sterilized.

In short, Francis Galton left behind a rather complex legacy. He made important contributions to a wide variety of subjects, such as his discoveries in Africa, his travel writings, statistics, and fingerprinting, but he also established eugenics, which paved the way to horrifying things.

Bibliography:

- Bulmer, Michael (2003). Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7403-1.

- Caprara, G. V.; Cervone, D. (2000). Personality: Determinants, Dynamics, and Potentials. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58310-7.

- Clauser, Brian E. (2007). “The Life and Labors of Francis Galton: A Review of Four Recent Books About the Father of Behavioral Statistics”. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 32 (4): 440–444. doi:10.3102/1076998607307449. S2CID 121124511.

- Conklin, Barbara Gardner; Gardner, Robert; Shortelle, Dennis (2002). Encyclopedia of Forensic Science: A Compendium of Detective Fact and Fiction. Oryx Press. ISBN 978-1-57356-170-9.