The British had a chance to rekindle the famous arctic expeditions with the Franklin expedition. It was a major difficulty for explorers of the 19th century to successfully navigate the treacherous Northwest Passage via the Arctic Ocean, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Following John Barrow’s recommendation, the Admiralty of the Royal Navy appointed Officer John Franklin, a veteran of previous successful Arctic voyages, as the ship’s captain. However, the one that set sail on May 19, 1845, became mired in the ice off the coast of King William Island. All 129 crew members perished between 1846 and 1848 due to exposure or illness. After the accident, scientists across the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries conduct a plethora of studies and inquiries to determine what went wrong. The Franklin expedition has become a myth.

- Who was behind the Franklin expedition?

- Why was the Franklin expedition launched?

- Who was John Franklin: The commander of the expedition

- What are the means implemented for the Franklin expedition?

- What was the journey of the Franklin expedition?

- Why did the Franklin expedition fail?

- What were the losses caused by the Franklin expedition?

- What were the results of the failure of the Franklin expedition?

Who was behind the Franklin expedition?

The Royal Navy was a symbol of English imperial supremacy in the early 19th century. Among the events that put Europe, Canada, and the United States on edge were the voyages organized by the Admiralty. To successfully navigate the Arctic Ocean’s Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific, between Davis Strait and Baffin Bay in the east and the Beaufort Sea in the west, had been a significant difficulty since the early 19th century.

This region links the Arctic Ocean to the northwest with Hudson Bay to the southeast. The Northwest Expedition of 1845 was spurred on by John Barrow. Barrow, who had been in his position as Second Secretary of the Admiralty since 1804 and was himself an explorer, had previously encouraged the journeys of William Edward Parry (1821), John Ross (1829), and James Clark Ross (1839). Even though he was 82 years old, he was the one who pushed the Royal Navy to proceed on the voyage to the North Canadian Archipelago.

Although he was eventually named captain, John Franklin almost didn’t take the helm. This was due to the explorer’s advanced age of 59. Barrow’s initial pick, William Edward Parry, turned down the offer, as did Barrow’s second choice, James Clark Ross. James Fitzjames, who at 35 was deemed too young, would nevertheless be participating in the expedition. There was an extended period of trying to get in touch with George Back, but ultimately nothing came of it.

Francis Crozier, a veteran of six arctic expeditions, was initially excluded due to his Irish ancestry but was ultimately admitted and named deputy on the expedition. William Edward Parry insisted that famed officer John Franklin, who had fought in many conflicts and expeditions, including the Battle of Trafalgar, be contacted. Just like Franklin told his wife on his last journey, this time it will be.

Why was the Franklin expedition launched?

With the Napoleonic Wars behind them, the British navy could focus on settling the uncharted areas of the Arctic and Antarctic. Because of the relative calm at the time, exploration became a platform from which the major Western nations could demonstrate their superiority in terms of both manpower and technology. The British Admiralty saw in polar exploration an opportunity to make a date after the notable discoveries made in this zone in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, by travelers who became famous, such as Frobisher, Davis, Hudson, Baffin, Knight, Middleton, Hearne, Cook, Mackenzie or even Vancouver. Particularly in the early 19th century, a big problem emerged: doubts about the existence of a navigable route in the temperate latitudes north of the Canadian archipelago arose as a result of a series of unsuccessful tests.

Numerous voyagers have fruitlessly attempted to traverse the frigid seas of the Arctic. A man named Giovanni Caboto, better known as John Cabot (1450–1498), passed away there. There was no success for Martin Frobisher (1535-1594). Both Henry Hudson (1565-1611) and James Cook (1728-1779) did as well. Between more recent times, in the years 1821 and 1823, Admiral William Edward Parry (1790-1855) gave it a go. Between 1829 and 1833, Rear Admiral John Ross (1877-1956) led an expedition that proved human life could be sustained in the Arctic. This trip made it possible to find the Magnetic Pole. At long last, the officer James Clark Ross (1800-1862) made many trips to the Arctic. They were unsuccessful in their attempt to navigate the fabled Northwest Passage.

Who was John Franklin: The commander of the expedition

British explorer, governor, and writer John Franklin served in the navy. On June 11, 1847, he passed away on King William Island; he was born on April 16, 1786, in Spilsby. The first time he enlisted in the Royal Navy, he was just 14 years old. The majority of his missions, as well as naval engagements in which he participated (such as the Battle of Copenhagen), have now become legendary. A member of Vice Admiral Nelson’s fleet, he fought with Nelson’s forces in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, when Napoleon attempted and failed to invade and conquer Great Britain.

In 1818, he joined Lieutenant David Buchan’s voyage to the North Pole in search of an ice-free sea. In the year following, he was given the position of assistant on the Coppermine expedition, which mapped the Canadian Arctic. He went back to the Arctic in 1829 to find the Beaufort Sea’s coast. Eleanor Anne Porden, a poet whom he married in 1823 and with whom he had a daughter before her death in 1825, was the mother of his child. In 1828, he married Tasmanian pioneer and avid traveler Jane Griffin.King George V (1829) knighted John Franklin in the Order of the Bath, and King William IV (1830) knighted him in the Royal Order of Guelph (1836). Tasmania, an island off Australia’s southeastern coast, named him governor (1837–1843).

What are the means implemented for the Franklin expedition?

Greenhithe, a town in Kent on the Thames in England, served as the expedition’s point of departure on May 19, 1845, and the resources used to ensure its success were enormous. Both the 378-ton HMS Erebus and the 331-ton HMS Terror were tried and true vessels that had served well on previous expeditions, most notably in Antarctica with James Clark Ross. The iron plate reinforcements and auxiliary steam propulsion systems on board are cutting-edge technologies developed in response to the ice.

Each vessel was outfitted with a library of over a thousand volumes, an internal steam heating system, a daguerreotype camera, and three years’ worth of canned food. It is for this reason that the expedition is also conducting a number of investigations in the fields of zoology, botany, magnetism, and geology. This goal is taken into account when picking the crew, which is comprised of young, strong, and experienced individuals. The crew of the John Franklin consists of 129 English sailors, 24 officers, and two glaciologists, Reid and Blanky. They are led by Franklin and his deputy, Captain Francis Rawdon Crozier. Without more evidence, DNA testing from 2017 suggested that four women were present on the expedition.

What was the journey of the Franklin expedition?

Franklin’s journey included the port of Stromness in Orkney, which is located in northern Scotland, at the request of the Admiralty. The ship received additional supplies and meat at Disko Bay, on the western coast of Greenland. Here is where the crew members will write their last letters home. As the Erebus and Terror waited for favorable circumstances in August 1845 to make the crossing from Devon Island to Baffin Island through Lancaster Sound, the expedition was last spotted in the Baffin Sea. This is the last mention of Europeans from this period in history.

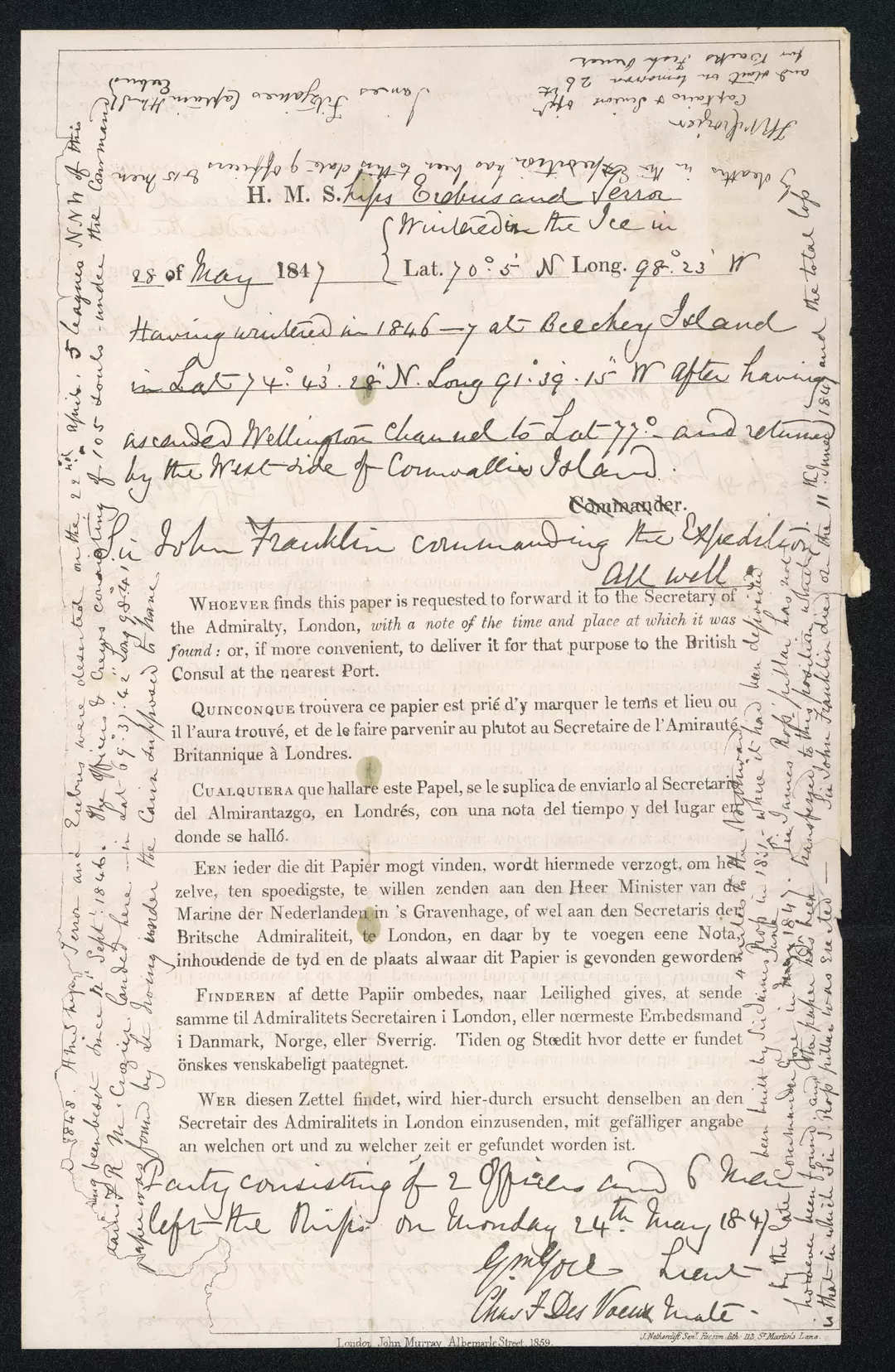

Thereafter, the route was a mystery that would be solved by other expeditions equipped with better tools over the course of the following 150 years. While spending the winter of 1845–1846 on Beechey Island, Franklin and his men buried three of their own. In 1846, the fleet made its way south to Peel Sound, close to King William Island, where it got frozen in. In all, 24 men had perished by April 25, 1848, when Crozier and Fitzjames left a letter on the island, with Franklin’s death on June 11, 1847, being the most recent. On April 26, 1848, the crew intended to depart from King William Island and make their way to Back River in the territory of Nunavut in Canada, from whence they would hopefully be able to find a passage to the Pacific.

Why did the Franklin expedition fail?

Franklin’s preferred route over King William Island’s western shore remains mostly frozen even in the summer, at least in that year. Contrary to the east coast, which was the route selected by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) between 1903 and 1906 in an attempt to reach the fabled passage. After spending two winters trapped in the ice in the Victoria Strait (between Victoria Island and King William Island), the crew realized they were ill-prepared for a land expedition and decided to abandon their ship.

Another factor that likely kept Europeans from attempting to adopt Inuit survival practices was a fundamental misunderstanding of such practices. As an added note, Inuit oral histories tell that the expedition’s male members perished due to hunger; nevertheless, research indicates that some of the males may have perished due to sickness. In a nutshell, the team lacked the necessary expertise and equipment for the journey, and they were also unfamiliar with the best paths to take.

What were the losses caused by the Franklin expedition?

Field investigations, exhumations, and forensic examinations beginning in the 1980s indicated that most of the crew members perished from a variety of illnesses, in addition to the effects of cold and starvation. Pneumonia, common colds, TB,scurvy, and even lead poisoning all contributed to the deaths of many men. The unique drinking water system on board was highly contaminated with lead. As well as a set of containers made of lead, closed lead cans, etc..

Autopsies performed on the “mummified” remains of John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine, discovered in August 1984 on Beechey Island, supported these findings. In the impermeable ice component known as permafrost, their bodies were preserved nearly perfectly for 138 years. On June 11, 1847, likely on King William Island, John Franklin passed away. At last, the shadowy details emerge: forensic medicine’s study of the bones shows cut marks “compatible with butchering,” leading to the idea that the remaining survivors resorted to cannibalism.

What were the results of the failure of the Franklin expedition?

It took two years before the Admiralty heard anything about the mission, at which point they sent out their first search party. There was a terrestrial expedition that followed the Mackenzie River all the way to its Arctic Ocean delta. Two others were sent out to sea with the intention of reaching the Canadian Arctic islands. In spite of this, all three attempts ended in failure. In 1850, the first human remains were found on the borders of Beechey Island by a fleet of 11 British ships and 2 American ships. Particularly moved by the graves of three sailors: John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine.

Later expeditions, including those led by John Rae in 1854 and James Anderson in 1855, discovered artifacts and human remains, especially on Montreal Island and at the mouth of the Back River in Chantrey Bay. On March 31, 1854, Britain officially declared the crew killed on duty and ended the hunt. On July 2, 1857, a second expedition led by Francis Leopold McClintock set out with funding from Jane Griffin, John Franklin’s widow. Multiple significant records were uncovered on this journey, including this one from April 25, 1848, which revealed that the two vessels had been stuck in the ice since September 12, 1846.

In the 20th century, investigations resume. Better identification of fresh human remains by contemporary forensics began with the initiation of the 1845–48 Franklin Expedition Forensic Anthropology Project (FEFAP) in June 1981. On September 7, 2014, the remains of the HMS Erebus were discovered south of King William Island. On September 12, 2016, the remains of the HMS Terror were discovered off the southwest shore of King William Island. The HMS Erebus and HMS Terror Shipwreck National Site, now jointly managed by Parks Canada and local Inuit, is closed to the public.