From 1789 until 1799, the French Revolution was a critical and turbulent era that ultimately led to the abolition of absolute monarchy. French constitutional monarchy gave way to republican rule under the National Convention, the Directory, and lastly the Consulate. The absolute monarchy of France was abolished during the revolutionary era of French history known as the French Revolution. The Estates General convened for the first time on May 5, 1789, and they lasted until Napoleon’s coup on November 9, 1799.

- Why did the French Revolution take place?

- What was the purpose of the Estates General convened in 1789?

- Why did the Storming of the Bastille take place?

- How did the Revolution put an end to the absolutism of Louis XVI?

- Why was the king guillotined during the Revolution?

- The Reign of Terror during the French Revolution

- How many people died during the Revolution?

- What are the consequences of the French Revolution?

- What are the symbols inherited from the French Revolution?

- The French Revolution: Chronology

After Louis XVI’s death, France transitioned from a constitutional monarchy to a republic, first under the National Convention, then the Directory, and eventually the Consulate after the Coup of 18 Brumaire. The French Revolution of 1789 is a pivotal time in French history since it marked the end of absolute monarchy in the country. Celebrations on July 14—the day on which rebels assaulted the Bastille—remain a symbol of the Revolution, the outcome of massive political and social changes. The concepts of the French Revolution have inspired mass uprisings all across the globe.

Why did the French Revolution take place?

King Louis XVI of France was expected to live up to the lofty standards set by his predecessors, Louis XIV and Louis XV, so when he took power in 1774, he was met with great anticipation. There was a serious financial crisis in the nation. The already dire situation was exacerbated by the brutal winter of 1788. Farmers and shopkeepers were hit the worst. Bread and other staple goods became more expensive. It was at this point that Louis XVI, feeling the pressure from the people (or Third Estate), called for the Estates General to be held. The Third Estate compiled the needs of the people in the “cahiers de doléances,” (or simply Cahiers) while the nobles and the Church were stubbornly trying to maintain their privileges.

What was the purpose of the Estates General convened in 1789?

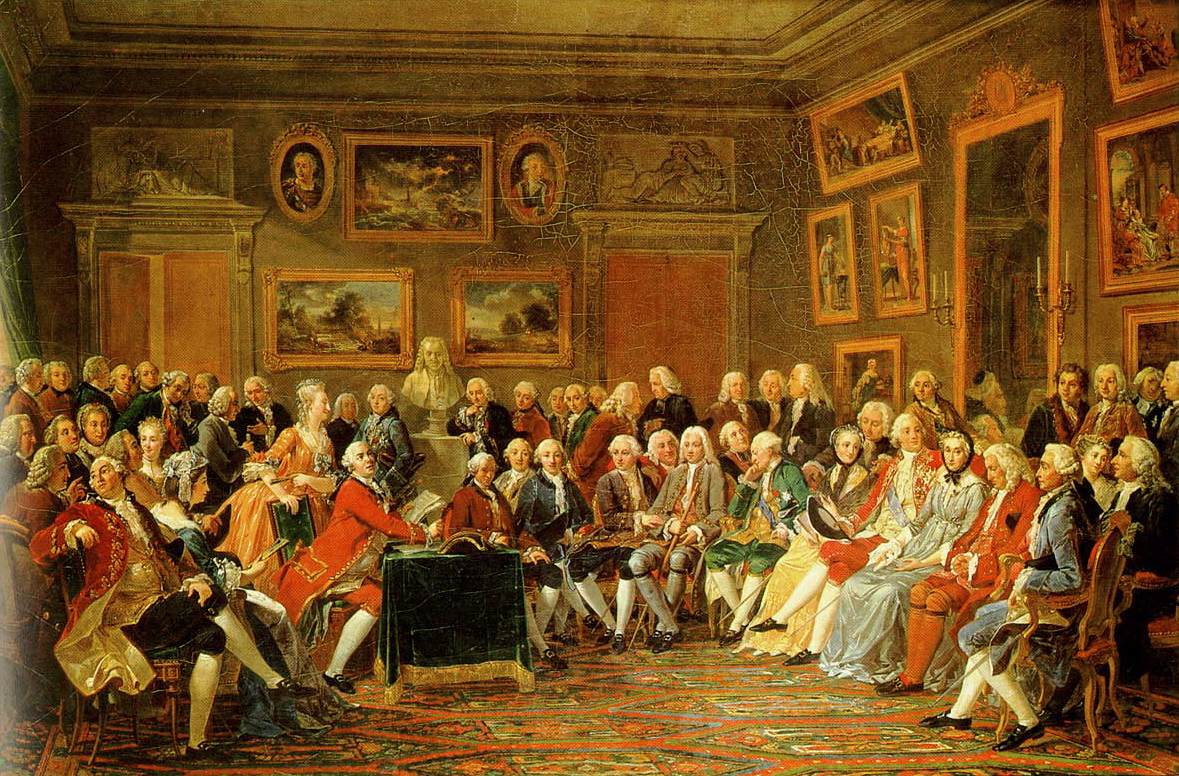

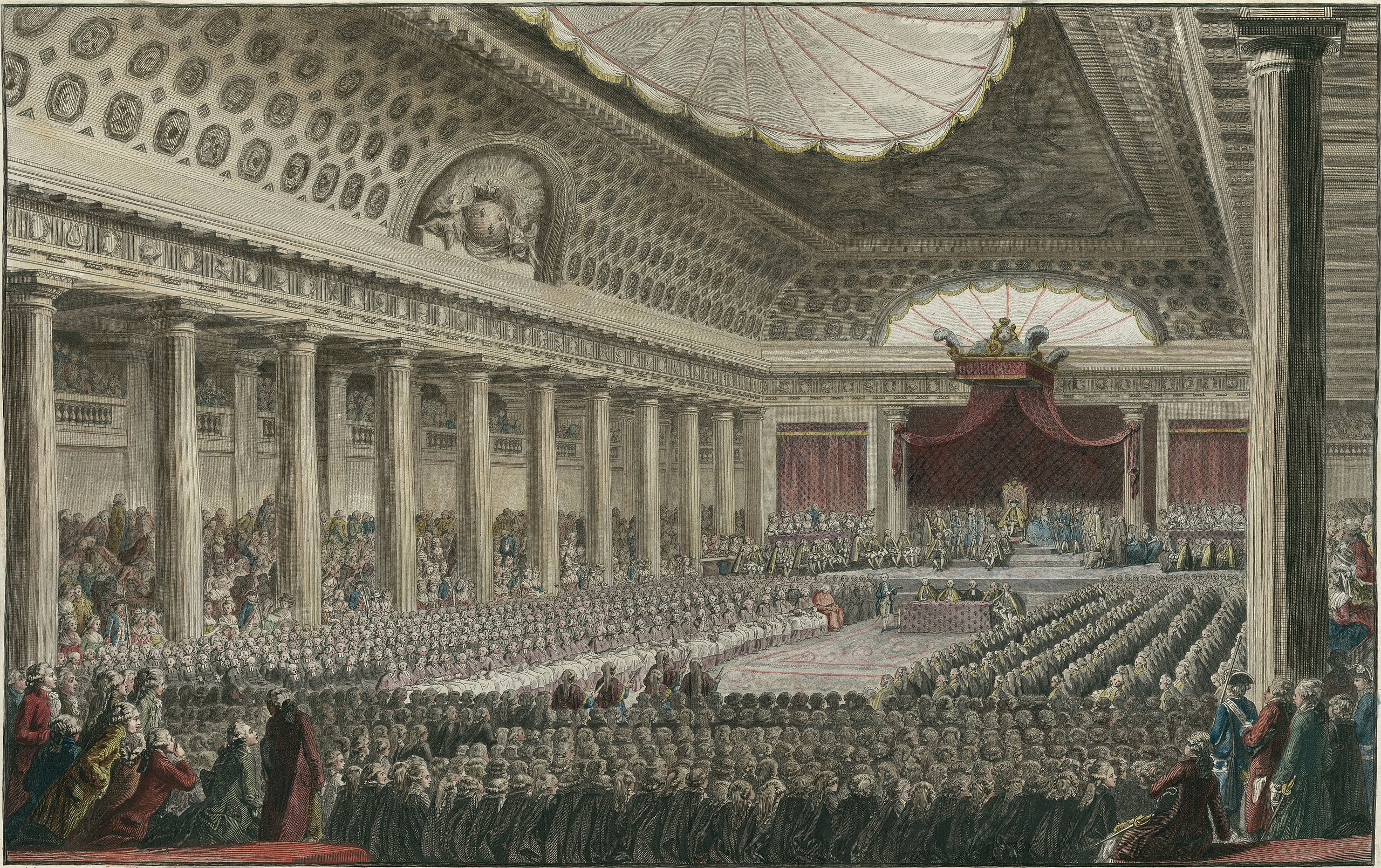

During the economic crisis that hit the monarchy in 1789, Louis XVI called for the Estates General. Around 1,150 delegates from the clergy (291), the aristocracy (270), and the Third Estate (578) gathered at Versailles on May 4, 1789 for the Assembly of the Estates General. In a speech that didn’t sugarcoat the country’s dire financial state, the French government was scheduled to unveil its budget deficit.

After confirming that the first votes would be conducted by order rather than by deputy, the king gives the go-ahead for the first ballots to take place. On June 17, 1789, the Third State rejected this approach and instead formed a more equitable National Assembly. The King shuts the door to the deputies’ meeting chamber as a sign of his disapproval. To that end, the new legislature convened in the Salle du Jeu de Paume (Jeu de Paume Room) and resolved to draft a constitution for France.

Why did the Storming of the Bastille take place?

Louis XVI, who felt threatened by the National Assembly, not only acknowledged its legitimacy but also sent 20,000 troops to Paris. The first riots in Paris started on July 9 after the removal of Minister of Finance Necker. The French Revolution’s defining moment was the Storming of the Bastille. On July 14, 1789, after the Parisian populace had already robbed the Invalides barracks in search of weapons for a larger insurrection, they assaulted the citadel turned into a jail. The Marquis de Launay (Bernard-René Jourdan de Launay) has been defending his building all day and has decided to give up and evacuate.

How did the Revolution put an end to the absolutism of Louis XVI?

A widespread panic known as the “Great Fear” struck France that summer of 1789. The nobility, so the rumor goes, has hired mercenaries to keep the peace. The commoners rose up in revolt and slaughtered the nobility. The revolt was put down on August 4, 1789, when the deputies agreed to do away with privileges. The tithe (levy) and corvée (forced labor) were both done away with. The land that the peasants farmed for a lord may now be purchased by the peasants themselves.

The Assembly also voted on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen on August 26, 1789. Civil Constitution of the Clergy was approved in July 1790. This divided Catholic clergy into two groups: those who have taken an oath to uphold the faith and those who refuse to do so, known as “refractory priests.” Louis XVI was exiled to the Tuileries Palace in October 1789. On June 21st, 1791, he made an attempt to leave the nation but was captured in Varennes. Constitutional Monarchy (a monarchy in which the king’s powers are constrained) was ratified in September 1791.

Why was the king guillotined during the Revolution?

Louis XVI was blamed for the string of military setbacks suffered by France and Britain in their war with Prussia. Towards August 10, 1792, the people of Paris rose up once again and marched on the Tuileries. The King sought protection from the Assembly when he was accused of treason. Responding to public pressure, the deputies establishes the National Convention, which votes to abolish the monarchy and usher in the First Republic (new political regime).

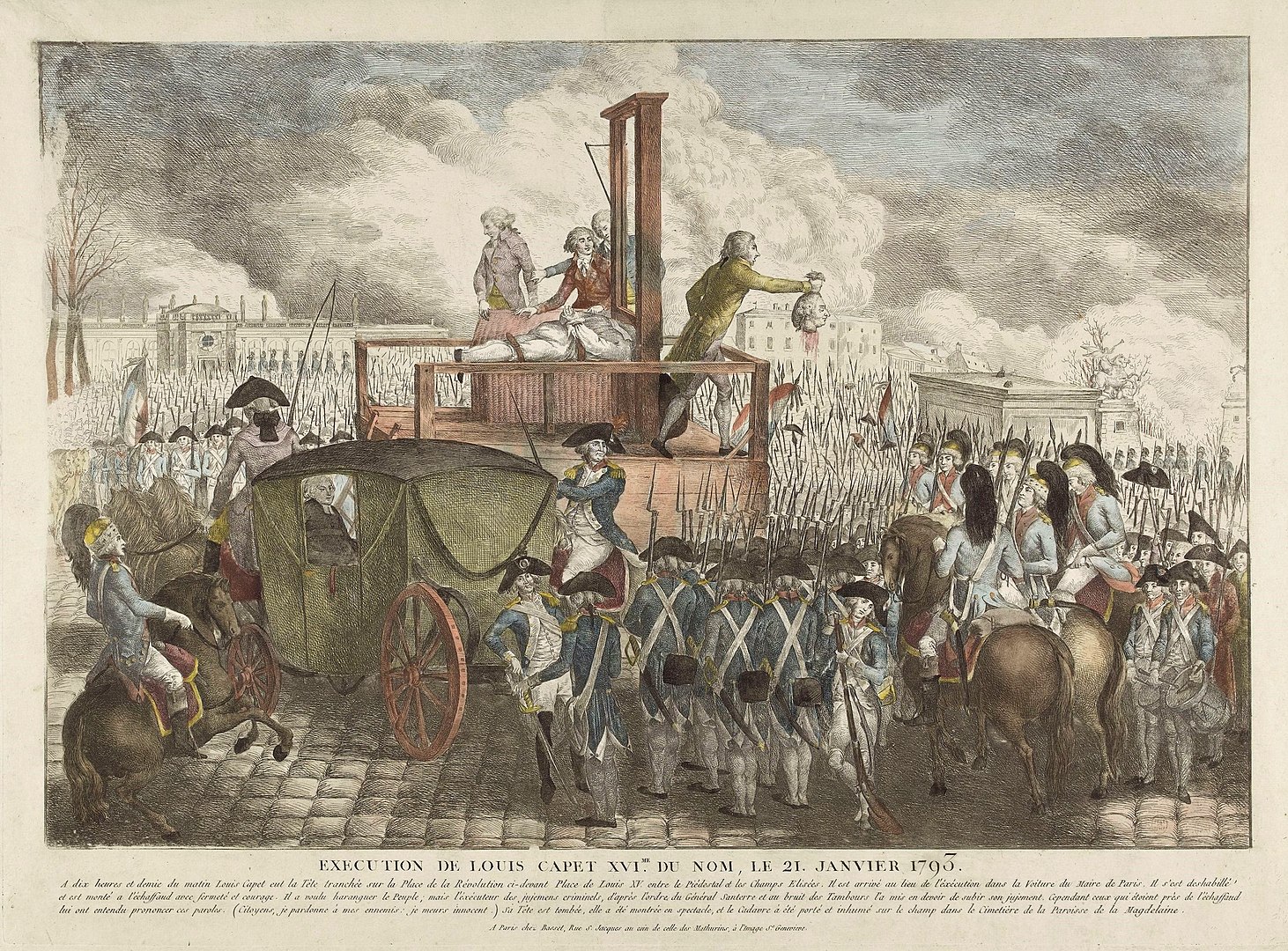

On August 13th, 1792, the monarch was arrested and thrown in jail. French King Louis XVI’s trial begins at year’s end, 1792. To many, his conviction on charges of conspiracy against public liberty and the general security of the state was the best way to ensure that no monarchy would ever return to power again. Louis XVI was guillotined on January 21, 1793, in the Place de la Concorde (Place de la Révolution) in Paris. Just days after the vote on his conviction, Louis XVI was beheaded.

The Reign of Terror during the French Revolution

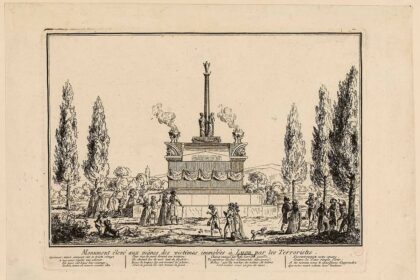

For years after the French Revolution, the country’s government was in disarray until the First Republic (1792–1804) took hold. Historians refer to the two years between 1793 and 1794 as the “Reign of Terror” in France. As a state of exception prepared to utilize armed force to confront internal and foreign crises, the revolutionary government was established to resist revolts and insurrections backed by other European monarchy.

France had to take on a European alliance before it could interfere in the War in the Vendée. Due to the increased danger, a legislation protecting anyone who could be suspects was passed. All potential opponents of the Revolution might be tried quickly and easily by revolutionary courts. Maximilien de Robespierre leads the National Convention and strengthens the Reign of Terror in June 1794. In July of 1794, a plot succeeded in bringing down Robespierre. The Reign of Terror ended with his death. The National Convention is dissolved and replaced by the Directory after the 1795 constitutional referendum.

How many people died during the Revolution?

Historians often have a heated dispute about the true death toll of the French Revolution. Few people can agree on a more or less accurate number to depict the human toll of this time in French history. It’s true that burning down so many libraries and museums isn’t helping them at all. Some estimates put the number of fatalities during Reign of Terror at about 40,000. About 600,000 to 800,000 people lost their lives during the French Revolution. There were more than 200,000 casualties, as most as 450,000, during the War in the Vendée.

What are the consequences of the French Revolution?

The overthrow of the Old Regime and the gradual installation of the First Republic are the primary political repercussions of the French Revolution. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which guaranteed the same rights and freedoms to all citizens, was one sociological impact of the French Revolution. An other improvement resulting from the French Revolution is the separation of powers. It also serves as the inspiration for other French icons like the national anthem and the tricolor flag. The instability brought on by the Revolution would set the ground for Napoleon Bonaparte‘s ascension to power on November 9, 1799.

What are the symbols inherited from the French Revolution?

There were major political and cultural changes as a result of the Revolution. Consequently, a number of period-specific symbols and allegories have been formally incorporated into the very fabric of the French Republic. Here’s a partial, not-complete list:

The flag of France is a tricolor, consisting of vertical stripes of blue, white, and red. It was created by the painter Jacques-Louis David and first used on February 15, 1794. Although it has been replaced multiple times since the Revolution’s conclusion, nothing has changed since 1830, when the July Monarchy took power. Paris’s iconic red and blue are used here, with the regal blue and white of a throne.

July 14, the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille in 1789 and of the Festival of the Federation (Fête de la Fédération) in 1790, stayed until 1880 as the national holiday.

The Marseillaise, a military song penned by Rouget de Lisle in 1792 as The War Song for the Army of the Rhine (Chant de combat pour l’armée du Rhin), has been France’s national anthem since 1795. (except from a few periods, notably the July Monarchy and the Vichy France Dictatorship).

The French Republic’s official mottoes are Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, (“Liberté,” “Égalité,” and “Fraternité,”) all of which can be traced back to the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

Adopted on August 26, 1789, with the primary aim of crafting a new constitution modeled on the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was a major step toward realizing that objective. It’s still regarded as a landmark piece of French legislation.

With the help of countless iconographic depictions (such as Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix in 1830), the young lady known as “Marianne” became, beginning in 1792, the allegory of liberty and of the Republic.

The French Revolution: Chronology

August 8, 1788: Louis XVI convenes the Estates General

After the monarchy’s inability to deal with the financial crisis, Louis XVI called for the Estates General to be held for the first time since 1614. In response to public pressure, the king agreed to increase the number of deputies from the Third Estate by 50 percent. In May 1789, 1,150 delegates from the three orders; First Estate (clergy), Second Estate (nobility) and Third Estate (commoners); gathered at Versailles to form the first National Assembly.

May 5, 1789: Opening of the Estates General

Due to the depletion of royal funds, Louis XVI calls for the Estates General to be held in Versailles. The Controller General of Finances, Loménie de Brienne, claims that only a national assembly of delegates can impose reforms (change the tax base) on the privileged and the Parliament.

June 17, 1789: The First National Assembly

The Third Estate, by a vote of 490 to 90, decides to form a National Assembly, in which it threatens to suspend tax collection if it is prevented from carrying out its mission of representation, denies the king the right of veto over its decisions, and calls for a “vote by head” that better reflects the will of the French people. The clergy will join this Assembly on June 19, and it will be declared “constituent” on July 9.

June 20, 1789: “We will only get out by the force of bayonets.”

The deputies took an oath to remain together in the Salle du Jeu de Paume on June 20, 1789, and Mirabeau replied to a deputy who wanted to remove the Third Estate from the chamber three days later, “We are here by the will of the people and we will only get out by the force of bayonets.”

June 27, 1789: Louis XVI bends to the Third Estate

Four days earlier, Louis XVI had asked the three orders to deliberate separately, and he had overturned all the tax decisions of the Third Estate. This one had then been joined by the majority of the deputies of the clergy and about fifty deputies of the nobility, led by the Duke of Orleans. Louis XVI, not daring to resort to force, submitted by enjoining the recalcitrant deputies to join the National Assembly.

July 9, 1789: Proclamation of the Constituent Assembly

Only a few weeks after the proposal of the deputies of the States General representing the Third Estate to organize a National Assembly with the objective of creating a Constitution, the Constituent Assembly was formally declared on July 9, 1789, and it sat until September 30, 1791.

July 11, 1789: Louis XVI dismisses Necker

The King of France fired Baron de Necker, the director general of finance, because he was too liberal, and replaced him with Breteuil. This decision sparked an uprising in the capital, as the French held Necker in high esteem. This Parisian unrest eventually led to the Storming of the Bastille on July 14 and the recall of Necker.

July 14, 1789: Storming of the Bastille

The Parisians revolted, exasperated by the king’s restrictions and inaction. On July 14, 1789, the Parisian revolutionaries attacked the Bastille with the firm intention of strengthening their armament. It was not a military incident, but the Storming of the Bastille is seen by many as the beginning of the French Revolution and is one of the most potent images of the period. The Parisians rebel after becoming frustrated with the constraints and the inactivity of the King.

August 4, 1789: Abolition of Privileges and Feudal Rights

The National Constituent Assembly declares that the feudal system and its privileges are no longer valid. The Storming of the Bastille and fears of aristocratic retaliation had sparked rural revolts. The peasants had besieged the seigniorial mansions, declaring their allegiance to the monarch. Concerned about his uprisings, the deputies determined to eradicate the vestiges of feudalism: corvée, tithe, seigniorial authority, and so on. The Assembly then gets to work on creating a magnificent Bill of Rights.

August 26, 1789: Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

The National Constituent Assembly votes on the final version of “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” after six days of debate. Article 1 states, “Men are born free and equal in rights,” and the rest of the document goes on to define the natural and imprescriptible rights of man, including the right to freedom, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

October 5, 1789: Parisian women demand bread

Several thousand women marched on Versailles on October 5, 1789, to complain to King Louis XVI about the high price of bread and other staples. The king was forced to sign privilege abolition decrees and move the royal family to the Tuileries Palace, effectively making them hostages of the Parisian populace.

November 1, 1789: Talleyrand proposes the confiscation of the property of the clergy

Talleyrand, Bishop of Autun, proposes to the Constituent Assembly that the clergy’s property be placed at the disposal of the Nation. On November 2, 1789, the decree is adopted by the Assembly, and the clergy’s property is confiscated to pay off the debts of the State. Afterwards, Talleyrand takes an oath to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

November 30, 1789: Corsica becomes French

Antoine-Christophe Salicetti, a delegate from Corsica, makes the following declaration in the Constituent Assembly: “Corsica is an integral part of the French Empire.” The island, which had been an autonomous province, is now a part of France and about to be department in 1790.

January 15, 1790: Creation of 80 administrative units

The Constituent Assembly passes a decree setting the number of departments at 83. These new divisions of the kingdom replace the Ancien Régime’s (Old Regime) 34 generalities or provinces. The size of the departments was defined so that every citizen could reach their department capital within a day’s ride. The deputies had intended to create geometric constituencies modeled after American states, but that proposal has been scrapped, and the departments’ borders would be based on those of the old provinces.

February 26, 1790: Creation of 83 French departments

As part of its reorganization, France’s Constituent Assembly renames and reduces the number of its departments to 83, with each department’s capital city situated in the geographic center of its territory to maximize accessibility by the citizens.

October 24, 1790: France adopts the tricolor flag

The white flag was officially replaced by the tricolor flag, the French flag, by decree of the Constituent Assembly in the young French republic. The tricolor flag is heavily influenced by the cockade that revolutionaries have been wearing since 1789, and it features blue and red, the colors of the city of Paris, and white, the color of the royal family.

November 27, 1790: The French clergy owes loyalty to the nation and the king

After deciding that bishops and priests should be elected by all, the Constituent Assembly voted to adopt a decree reforming the status of the clergy, which stipulated that each member of the clergy must henceforth take an oath of loyalty to the nation, the law, and the King; failure to do so would result in the revocation of their ordination. The Pope condemned these laws, and about 45% of the clergy refused to obey them.

June 21, 1791: Louis XVI is arrested at Varennes

In the “Flight to Varennes,” King Louis XVI and some of his family try to escape to Montmédy to start a counter-revolution, but they are captured and taken into custody instead. This event, which occurred on the night of June 21-22, 1791, is widely regarded as a betrayal of the French and marks the beginning of the end of Louis XVI’s reign.

July 17, 1791: Champ de Mars massacre

Thousands of people gathered on the Champ de Mars after Louis XVI’s arrest in Varennes to call for his deposition and the proclamation of a republic. The constituents ordered the national guard to shoot at the demonstrators, and under La Fayette’s command, about 50 people were killed. The Constituent Assembly was not ready to dismiss Louis XVI, and the king regained his rights in mid-July.

September 14, 1791: Louis XVI and the constitutional monarchy

On September 14, 1791, Louis XVI was invited to take the oath of office and became king of french under a constitutional monarchy that broke with the old absolute monarchy that existed in France before the Revolution. This date marks the entry into force of the French Constitution of September 3, 1791.

September 16, 1791: Annexation of Avignon

The French Constituent Assembly resolved to acquire Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin. Unlike the other cities of the Comtat, which were more rural and conservative, the “city of the Popes” or Avignon, which was industrial and commercial, had decided to reject the pope from the beginning of the French Revolution. The argument was finally over with the 14 September decree.

April 20, 1792: Louis XVI declared war on Austria

French armies retreated at first, much to the delight of counter-revolutionaries. However, an unexpected patriotic impulse emerged, sealing the alliance of the people in arms and the Revolution, and ultimately leading to the downfall of the monarchy, with Louis XVI being tried for political treason and executed on January 21, 1793.

April 25, 1792: First use of the guillotine

From September 1793 to July 1794, nearly 50 guillotines were installed in France, and approximately 20,000 people were executed. The guillotine utilized last in 1977. The guillotine was inaugurated during the execution of highwayman Nicolas-Jacques Pelletier in Paris in 1789. Doctor Joseph Guillotin presented his beheading machine to the Constituent Assembly.

April 25, 1792: The Song of Rouget de Lisle

On April 25, 1792, French military officer, poet, and playwright Joseph Rouget de Lisle wrote a patriotic song in the context of the military war with Austria. This patriotic song, or “revolutionary war song,” was adopted by the federates from Marseille upon their entry into Paris in July 1792, at which point it was renamed “La Marseillaise” and ultimately selected as the national anthem of France.

June 20, 1792: The Sans-Culottes at the Tuileries

On the anniversary of the Jeu de Paume oath, Parisians marched on the Tuileries Palace at the suggestion of Santerre, a brewer from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. They want the monarch to lift his veto on ordinances authorizing the expulsion of recalcitrant priests and the establishment of a national guard camp. The King wears the red hat and drinks to the nation’s health, but he does not yield. A month later, the Parisians returned with many battalions of federates and seized the Tuileries Palace.

July 30, 1792: The Marseillais enter Paris singing

After many days of marching, the troops of the revolutionary army from Marseille arrived in Paris. On this occasion, they performed the legendary “War Song for the Army of the Rhine,” which is none other than Rouget de Lisle’s Marseillaise from a few months earlier. In 1795, the song was designated as a “national song.”

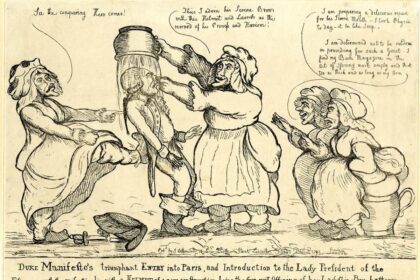

July 25, 1792: The Brunswick Manifesto

In a letter, the Duke of Brunswick, commander of the Prussian army, declares that if the lives of the French royal family are endangered, he would demolish Paris. The king is quickly accused of treason and of conspiring with the enemy to disorganize the French army. The sans-culottes, aided by the Marseillais federates, stormed the Tuileries on August 10, 1792, forcing the royal family to seek sanctuary in the Assembly. On the same day, the French monarchy was abolished by the Legislative Assembly, which appointed a temporary executive body to replace the King’s Council and its ministers. On August 13, the king is imprisoned.

September 2 to 7, 1792: September Massacres

The Princess de Lamballe, the supervisor of the Queen’s household, was killed along with other royalist prisoners and recalcitrant priests when the Revolutionaries stormed the jails in response to reports of royalist schemes and Prussian invasions.

September 20, 1792: Battle of Valmy, French victory

It was at Valmy that the French army, under the command of Generals Dumouriez and Kellermann, unexpectedly defeated the Prussians of the Duke of Brunswick, putting an end to the monarchist powers’ invasion of revolutionary France. The Prussians had been able to invade eastern France without much resistance since the August 1792 arrest of Louis XVI. Valmy represents the Republic’s first military triumph. “From today and from this place dates a new era in the history of the world,” Goethe, who observed the cannonade, declared.

September 22, 1792: Abolition of the French Monarchy

After hearing arguments from Collot d’Herbois and the Abbe Gregoire, who said, “Kings are in the moral order what monsters are in the physical order. The courts are the workshop of crime, the hearth of corruption and the den of tyrants. The history of kings is the martyrology of nations.” The Convention, the legislative body, abolishes the monarchy in its first session and declares the following day to be Year I of the Republic.

November 6, 1792: Battle of Jemappes

40,000 volunteer soldiers from the French Revolution route the Austrians in Belgium. Since the Duke of Saxe-Tesch was forced to leave the land, French General Dumouriez has assumed control the for France.

December 10, 1792: The Trial of Louis XVI

The trial of King Louis XVI began on December 16, 1792, and concluded on December 26, 1792, after a vote by the National Convention on December 3, 1792. The deputies voted in favor of a death sentence for Louis XVI on January 15, 1793, accusing him of fleeing to Varennes and ordering gunfire at the people.

January 21, 1793: The execution of Louis XVI

Louis XVI was transported to the Place de la Concorde and guillotined there six days after the judgement in his trial. One of the most significant incidents of the French Revolution and French history is the execution of Louis XVI.

February 23, 1793: The Convention decides the conscription of 300,000 men

Since an English landing is still a possibility, the revolutionary army needs to bolster its forces. The Girondins, who were in charge of the Convention, made the decision to respond by conscripting 300,000 men. This widespread draft was met with disapproval, particularly in Lyon. In addition, it was the spark that started the Wars of the Vendée.

March 10, 1793: Creation of the Revolutionary Court

Fouquier-Tinville, the Prosecutor of the Republic, assesses whether or not suspects should be tried by the Revolutionary Institution, an exceptional tribunal created by the Convention. The Revolutionary Court was established to combat any counter-revolutionary endeavor, any assault on freedom, any royalist conspiracy, and it was to do so until May 31, 1795.

March 10, 1793: Massacre of Machecoul

In early March of 1793, numerous towns (including Chemillé, Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, Tiffauges, etc.) rebelled against the National Convention in response to the National Convention’s conscription of 300,000 men on February 23. On the morning of March 11, 1793, a large group of people assaulted the town of Machecoul in an effort to halt the ongoing recruitment drive.

March 14, 1793: Cholet in the hands of the Vendéens

First Battle of Cholet occurred on March 14, 1793. Cholet fell to the rebels during the Vendée War, despite the Republicans’ superior numbers (the “Blues”). Jacques Cathelineau commanded the Vendéens, often known as the “Whites”. Between 150 and 350 people died in the conflict, with the vast majority of those casualties being on the Republican side.

March 18, 1793: The Battle of Neerwinden

At Neerwinden, the French commander Dumouriez was soundly defeated. The French army was driven out of the area after being attacked by the Austrian Duke Frederick of Saxe-Coburg. Although the French triumph at Jemappes was long in the past, in 1794 France was able to reclaim Belgium after defeating Britain and the Dutch in the Battle of Fleurus.

April 2, 1793: The Convention declares Paoli a traitor to the France

The Convention proclaimed Pascal Paoli, a hero of the Corsican War of Independence and the Wars of the French Revolution, a traitor to the French on April 2, 1793. Suspicious dealings with England and his resistance to the Kingdom of France were among the charges leveled against him.

May 31, 1793: The Girondins are overthrown by the Montagnards

The days of May 31 and June 2, 1793, were a turning point in the battle between the Girondins and the Montagnards, only a few weeks after Dumouriez’s treachery. During the First Insurrection on May 31, a petition was circulated calling for the destruction of the Commission of the Twelve, a special commission constituted by the Girondins in response to the calls of Robespierre and the Enragés. A second uprising occurred on June 2, 1793, after which the Girondin leaders were arrested.

June 9, 1793: The Vendéens took Saumur

During the height of the uprising, on June 9, 1793, the Vendéens engaged in a bloody fight with the Republicans. Finally, the remnants of the Republican soldiers trapped in the city’s castle surrendered to the Vendéens, allowing them to take Saumur. Next, the “Whites” captured Angers without much fight, but in Nantes, the resistance was able to become organized.

June 29, 1793: Nantes resists the Vendée insurrection

Following their success in Saumur, the Vendéens immediately dove into the Battle of Nantes. Jacques Cathelineau’s force of about 30,000 Vendeans was ultimately beaten by Republican forces led by Jean-Baptiste-Camille de Canclaux, who were better equipped. Unfortunately, Cathelineau was killed in action.

July 13, 1793: Assassination of Marat

Doctor and deputy Jean-Paul Marat was shot dead by Charlotte Corday on July 13, 1793, when he was in the bathroom. Marat’s death caused an immediate elevation to the status of martyr in the eyes of his admirers. Known as “The Friend of the People,” Marat had a pivotal role in the events leading up to and during the French Revolution.

August 1, 1793: The Committee of Public Safety creates the army of the west

The Comité de Salut Public established the Army of the West on August 1, 1793 to combat the Vendée uprising. In the name of the French Revolution, Kléber united many troops, notably the army of Mainz and the army of the coast of Brest.

September 17, 1793: The Reign of Terror votes the “Law of Suspects

A decree enabling the arrest of any confessed or probable adversary of the Revolution was approved by the Montagnard-led National Convention after the “Reign of Terror” regime was established on September 5. This decree was sponsored by Philippe-Antoine Merlin de Douai and Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès.

October 10, 1793: Saint-Just declares the Convention

At the urging of 27-year-old Louis-Antoine Saint-Just, the provisional Convention declares that “the French government will be revolutionary until peace.” This law further escalates the Reign of Terror that began with the massacres in September 1792. The executive council was placed under the supervision of the Convention on the basis of the revolutionary principle that “it is impossible for revolutionary laws to be executed if the government itself is not constituted revolutionaryly”.

October 14, 1793: Marie-Antoinette before the Revolutionary Court

The wife of Louis XVI was brought before the accuser, Fouquier-Tinville, on October 14, 1793, marking the beginning of the swift trial of Marie-Antoinette before the Revolutionary Court. Among the charges against her were conspiracies with foreign powers, involvement in the plot, and the installation of civil war within the Republic.

October 16, 1793: Marie-Antoinette is guillotined

Marie-Antoinette was condemned to death by guillotine following a two-day trial, and she was put to death the same day. The time between the pronouncement of the judgment and her execution at the Place de la Concorde was less than three hours.

October 17, 1793: The Vendéens lose Cholet

The Second Battle of Cholet was fought on October 17, 1793, after the Vendean army was defeated at La Tremblaye the day before and attempted to retake the city of Cholet from the Republicans. With 40,000 men, the Whites launched an attack north of the city, but the Blues, led by Jean-Baptiste Kléber, resisted the assault and held the city. The Vendeans then decided to flee with their women and children in the direction of Laval to join the Chouans on their journey to Galerne.

October 26, 1793: Couthon begins the destruction of Lyon

In Lyon, the city that had become the center of Jacobin agitation and, according to the Convention, had to be destroyed. The Montagnard, Georges Couthon, a faithful friend of Robespierre, began the demolition of a house in the Place Bellecour. However, as a member of the Committee of Public Safety, Couthon could not bring himself to apply the decree of the Convention, and was replaced by Collot d’Herbois and Fouché to complete this task.

November 6, 1793: Philippe-Egalité dies on the scaffold

A fervent revolutionary, the Duke of Orleans was the cousin of Louis XVI. During the trial of the King of France, he did not hesitate to vote for his death. In 1792, he decided to take the name Philippe-Egalité, but the Convention did not consider him trustworthy and imprisoned him in Marseille in April. His son, Louis-Philippe Joseph of Orleans, was guillotined in Paris for wanting to restore the monarchy.

November 10, 1793: Notre-Dame de Paris, Temple of Reason

Once a symbol of Catholicism, Notre Dame de Paris found a new purpose after the destruction it endured during the Revolution: Temple of Reason. The Paris Commune decided to incorporate the city’s cathedral into the new religion, the cult of the Supreme Being, which had been established by the deists to symbolize and represent the Republic and its values. This new religion took over many buildings while the Convention aimed to replace it definitively with Catholic worship.

November 24, 1793: The publication of the revolutionary calendar

The new republican calendar, often known as the French or revolutionary calendar, was first published on November 24, 1793. This calendar, created by the revolutionary Fabre d’Églantine, is differentiated by weeks of 10 days and months of 30 days, each with a name that refers to the seasons (such as pluviôse or ventôse).

December 13, 1793: The Vendée army decimated at Le Mans

The Vendée Army, already reeling from a loss at Angers, was decimated by the Republican Army at Le Mans on December 13, 1793. Between 10,000 and 20,000 people were killed or captured during this conflict, making it the worst engagement of the Vendée War.

December 23, 1793: The Galerne expedition ended at Savenay

This military campaign (Virée de Galerne), which is an unforgettable part of the Vendée War, began on October 18, 1793, after the defeat of Cholet, and ended on December 23, 1793, with the decisive victory of the Republican forces in Savenay. The purpose of this Vendée War military operation was to rouse the Chouans in anticipation of a British arrival. Initially successful, the Whites eventually suffered a series of defeats, and at Savenay, the last combatants tried to return home with women and children. They are apprehended while attempting to cross the Loire. 50,000 to 70,000 individuals are killed.

January 21, 1794: Turreau’s infernal columns attack the Vendée

The “infernal columns” led by republican general Turreau were dispatched to the Vendée on January 21, 1794, with the mission of eradicating all male and female counter-revolutionaries who had taken part in the revolt, as well as their property and land. These exactions became commonplace not only in the Vendée, but also in the neighboring regions of Maine-et-Loire, Deux-Sèvres, and Loire-Inférieure.

February 15, 1794: The French Navy adopts the tricolor flag

In 1794, at the suggestion of Pastor André Jeanbon, the National Convention declared that beginning with the 1st prairial year II (May 20, 1794), the flag will be formed of the three national colors laid out in three equal bands posed vertically. This allowed for the standardization of the French Navy; in 1812, Napoleon I extended this measure to the regiments of the army. Finally, in July 1880, the blue, white, and red flag was officially adopted by the Third Republic

February 20, 1794: Bourbon Island becomes Reunion Island

The Convention renames Bourbon Island, a French possession since 1649, to Reunion Island in honor of the federates from Marseille and the Parisian National Guards who met on August 10, 1792, to storm the Tuileries Palace and suspend the powers of King Louis XVI. The island’s original name will be reassigned during the English occupation of the Indian Ocean from 1810 to 1815, and the Second Republic will finally give it back the name of Reunion Island.

April 5, 1794: Danton and Desmoulins at the scaffold

Georges Danton was tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal beginning on April 2, 1794. Danton was found guilty of embezzlement and was sentenced to death by a jury of seven. On April 5, 1794, he was guillotined along with 14 other “indulgents,” including Camille Desmoulins, Hérault de Séchelles, and Fabre d’Eglantine.

May 7, 1794: The Cult of the Supreme Being

The Convention establishes a new religion, the cult of the Supreme Being, by decree. Robespierre, influenced by the ideas of 18th-century philosophers, saw in it a metaphysical foundation for republican ideals. However, the celebration of the Supreme Being angered the Montagnards and failed to pique the interest of the people. Robespierre, the man at the center of the Reign of Terror, was guillotined on July 28, 1794.

June 10, 1794: The Convention decrees the Terror

By decreeing this Reign of Terror, the Convention leaves the jurors of the revolutionary tribunals with just two possible verdicts: acquittal or death sentence. The Reign of Terror, which had been present since 1793, reached its height on June 10, 1794.

June 26, 1794: French victory at Fleurus

As a result of the reorganization of the army by Lazare Carnot, member of the Committee of Public Safety (Comité de salut public), the French of the Army of the North, commanded by General Jourdan, won a decisive victory over the Austrians of the Prince of Saxe-Coburg at Fleurus, opening Belgium to the Republican armies. Two weeks later, Jourdan joined Pichegru’s armies in Brussels.

July 27, 1794: End of the Reign of Terror

In the stands of the Convention, Maximilien Robespierre heard chants of “Down with the tyrant!” Many people disapproved of him because he instituted a system of eavesdropping on the parliamentarians and because the statute of 22 prairial (June 10) that set up the “Great Terror” was passed with his approval. Most conventionals became part of the group’s membership. Next day, roughly twenty Jacobins, including Robespierre “the Incorruptible” and Saint-Just “the Archangel of the Terror,” as well as Couthon, young Robespierre, Maximilian’s brother, and others, were hanged without trial. The Jacobin Club was disbanded and the Thermidorian Republic was formally declared as a result of the Convention.

February 17, 1795: Treaty of La Jaunaye

The first Vendée War was supposed to be settled by a treaty signed between the Vendeans and the Chouans and deputies of the Convention on February 17, 1795. The agreement was formalized at the nearby town of La Jaunaye, a manor home. A few months later, several of the treaty’s main players, including Charette, once again resorted to violence.

February 21, 1795: Restoration of freedom of worship in France

By announcing religious freedom, the Convention put an end to five years of religious discrimination. Since that time, citizens have been free to practice any religion they like, but the government requires that no public displays of religious fervor be made and refuses to be obligated to provide facilities for religious gatherings.

June 23, 1795: Landing of Quiberon

Several thousand refugees arrived at Quiberon on June 23, 1795, to fight against the Revolution. The English-led military effort to rise the West of France which was controlled by England continued until July 21. The arrival at Quiberon was distinguished by the royalist party’s failure due to their lack of preparation.

October 5, 1795: Bonaparte’s first intervention in Paris

To restore the monarchy, royalists attempted a coup de force in Paris at the start of October 1795. Royalists watched as the Convention army, headed by the youthful brigadier general Napoleon Bonaparte, mercilessly suppressed and destroyed this revolt a few months after the tragedy of the Quiberon Landing. Paul Barras, head of the Interior Army, was given the name by his lover Joséphine de Beauharnais.

October 26, 1795: Beginning of the Directory

France enters a new political era after three years under the Convention. As decided by the Thermidorians, this is the Directory and Constitution of Year III. Four years of attempted coups against the Directory culminated in the 18 Brumaire revolt, commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte (now the head of the interior army). This led to the foundation of the Consulate.

December 26, 1795: Madame Royale as a bargaining chip

Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, daughter of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette and known by her moniker “Madame Royale,” was handed over to the Austrians in Basel after being detained by the Revolutionaries of the Directory. Austria released Camus, Beurnonville, Lamarque, Quinette, Bancal, and Drouet in return for French prisoners taken by the Austrians in the Battle of Maubeuge in October 1793. Once again reunited with her loved ones, Madame Royale has returned home. She married Louis-Antoine de Bourbon, Charles X’s son and the last dauphin of France, in 1799.

January 1796: Creation of the Ministry of Police

The Directory institutes a Ministry of General Police in lieu of the former several committees responsible for policing French territory. Former Justice Minister Merlin de Douai has stepped down to head up the new Ministry of Justice. The General Police’s goal was to crush “subversive enterprises,” a code phrase for Jacobin groups.

July 15, 1796: End of the Vendée War

The Vendée War, which began on March 3, 1793, was finally put to rest in the summer of 1796 when the Republicans triumphed and the most prominent Vendéen commanders, Charette and Stofflet, were put to death. Approximately 200,000 people lost their lives in the several engagements that took place during this war, which pitted Republicans against Royalists in western France.

September 10, 1796: The Directory crushes the “Babouvistes”

Grenelle camp troops were led in an uprising against the Directory by the last remaining devotees of French agrarian communist thinker Babeuf. The militants were denounced and tricked into entering a trap. Extreme leftist revolutionaries were defeated.

October 1796: The French army regains control of Corsica

The French troops retook the Kingdom of Corsica in October 1796 after it had been ceded to the British in 1794 due to Paoli’s treachery. With their position in the Mediterranean more tenuous, the British withdrew their soldiers from the island, leaving it to the French. The French quickly took advantage of the situation and split the island into two administrative divisions.

November 17, 1796: Bonaparte victorious at Arcole

In the first Italian war, Bonaparte defeated the Holy Roman Empire in the Battle of the Arcole Bridge after two days of intense battle. Napoleon Bonaparte’s strength was bolstered by his victory against the Austrian army despite the loss of 3,500 troops (killed and wounded). The Austrians surrendered at Mantua, and the Italian campaign concluded with the Treaty of Campo-Formio.

January 14, 1797: Battle of Rivoli

Napoleon Bonaparte’s army defeated Baron d’Alvinczy’s Austrians. Thanks to this victory, General Wurmser capitulated and Austria lost Mantua, which they were tasked with defending. In the aftermath of the defeat, Alvinczy surrendered approximately 5,000 captives to the French.

February 19, 1797: Treaty of Tolentino

After Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Italy, the Pope’s delegates were cornered into signing the Treaty of Tolentino, in which his Papal States conceded significant territory. The Pope was forced to relinquish the legations at Bologna, Ferrara, and Romagna in addition to Avignon and the Comtat de Venaissin, which were retained by France. These devastating losses are in addition to the amount of 30 million livres that the Papal States must pay France as part of the Armistice of Bologna. But the pact did not challenge the pope’s temporal authority.

September 4, 1797: Coup of 18 Fructidor

In order to prevent the two Assemblies from meeting, General Pierre Augereau was sent to Paris by the Directory at the behest of General Napoleon Bonaparte (Council of Elders, Council of 500). 42 legislators were expelled after being accused of having royalist leanings, and the death sentence was made applicable to anybody who supported restoring the monarchy. Averting the danger posed by elected moderates who were making plans to restore the monarchy, the Directory was preserved. Bonaparte is called upon again two years later, but this time he takes the initiative to form the Consulate on his own.

October 18, 1797: Signature of the Treaty of Campo-Formio

Located in the Province of Udine, Campo-Formio is where the French and Austrian armies signed a peace treaty that ended hostilities in Italy. On the French side, the pact was primarily signed by Napoleon Bonaparte. On behalf of the Holy Roman Empire, Count Louis de Cobentzel was present.

January 28, 1798: Mulhouse joined the French Republic

The city’s three-hundred-year period of autonomy came to an end with the Treaty of Mulhouse, which permanently annexed it to France. The majority of the city’s prominent citizens voted on January 4 to approve the attachment.

April 15, 1798: Geneva loses its independence

The Directory government of France (1795–1799) ordered the invasion and occupation of the neutral Republic of Geneva by French forces. They seized Switzerland a few weeks earlier and modeled the new Swiss Republic after French’s unified government. Subsequent to its annexation, the city became the administrative center for the Geneva Department. After Napoleon I’s defeat in 1814, Geneva regained its independence and joined the Helvetic Confederation.

May 11, 1798: The coup of 22 Floréal year VI

The five Directors, who exercised the administrative authority, disrupted the elections of the Assemblies because they were too advantageous in their view to the Jacobins, enthusiasts of a social revolution. Some of the Directors even started hoping for a military dictatorship to cease the constant bickering among themselves. In 1799, once General Bonaparte returned from Egypt, he destroyed the Directory government and he was now able to become the First Consul.

July 21, 1798: Battle of the Pyramids

The left bank of the Nile, on the Giza plateau, was the site of the Battle of the Pyramids. Napoleon Bonaparte’s French army and the Mameluke forces headed by Murad Bey and Ibrahim Bey fought each other during Egypt’s war. This fight was won by the French army and paved the way for Bonaparte’s entry into Cairo three days later.

August 1, 1798: The French fleet is destroyed at Aboukir

The French army suffered a devastating loss in the Battle of Aboukir, often known as the “Battle of the Nile,” during the Egyptian war. The Royal Navy, headed by Admiral Horatio Nelson, defeated the French navy at the Bay of Aboukir in less than two days. Due of this, Napoleon’s army was stuck in Egypt, cut off from returning home.

October 11, 1798: Rout of the French Fleet in Ireland

Commodore Warren’s English fleet hunted and destroyed the Bompard division, which consisted of eight ships and 2,900 soldiers, in the northwest of Ireland. The Catholic revolt in Ireland had began in April, and France planned to send troops there to help it.

April 16, 1799: The Battle of Mount Tabor

At the Battle of Mount Tabor, the French Army triumphed over the forces of the Ottoman Empire, and the leader of the Mamelukes (Palestine). With the goal of weakening British influence in the eastern Mediterranean and seizing control of the road to India, General Bonaparte sent an expedition to Egypt in 1798. After this triumph, he pressed on, but he was ultimately unable to capture St. John in Acre. Despite Bonaparte’s military defeat in Egypt in 1801, the field of Egyptology was able to flourish because to the efforts of the professors Bonaparte had brought with him.

October 8, 1799: Bonaparte returns from Egypt

Napoleon Bonaparte decided to return to France after a lengthy campaign in Egypt. The 47-day voyage concluded at Saint-Raphal, where the future Emperor of France disembarked before continuing on to Paris. The future emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, quietly plotted his overthrow by meeting with influential figures like Talleyrand.

November 9, 1799: Coup of 18 Brumaire

The French Revolution ended with the coup on the 18th of Brumaire. On November 9, 1799, the three Consuls—Napoleon Bonaparte, Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, and Roger Ducos—were provisionally appointed by the deputies in an effort to “save the Republic.” The plot was hatched by Napoleon Bonaparte, his brother Lucien (President of the Council of Five Hundred), and Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès. The man destined to become Emperor was promoted to First Consul.

December 13, 1799: Birth of the Consulate

The new constitution is officially adopted and is now referred to as the Constitution of the Eighth Year. Daunou’s draft reduces the power of the legislature while giving three consuls appointed by the Senate more authority over the executive branch for a decade. It’s true that Bonaparte, Cambacérès, and Lebrun were all chosen as consuls, but ultimately only Bonaparte would wield any real influence. The Constitution of the Eighth Year officially ended the Revolution by creating the Consulate.