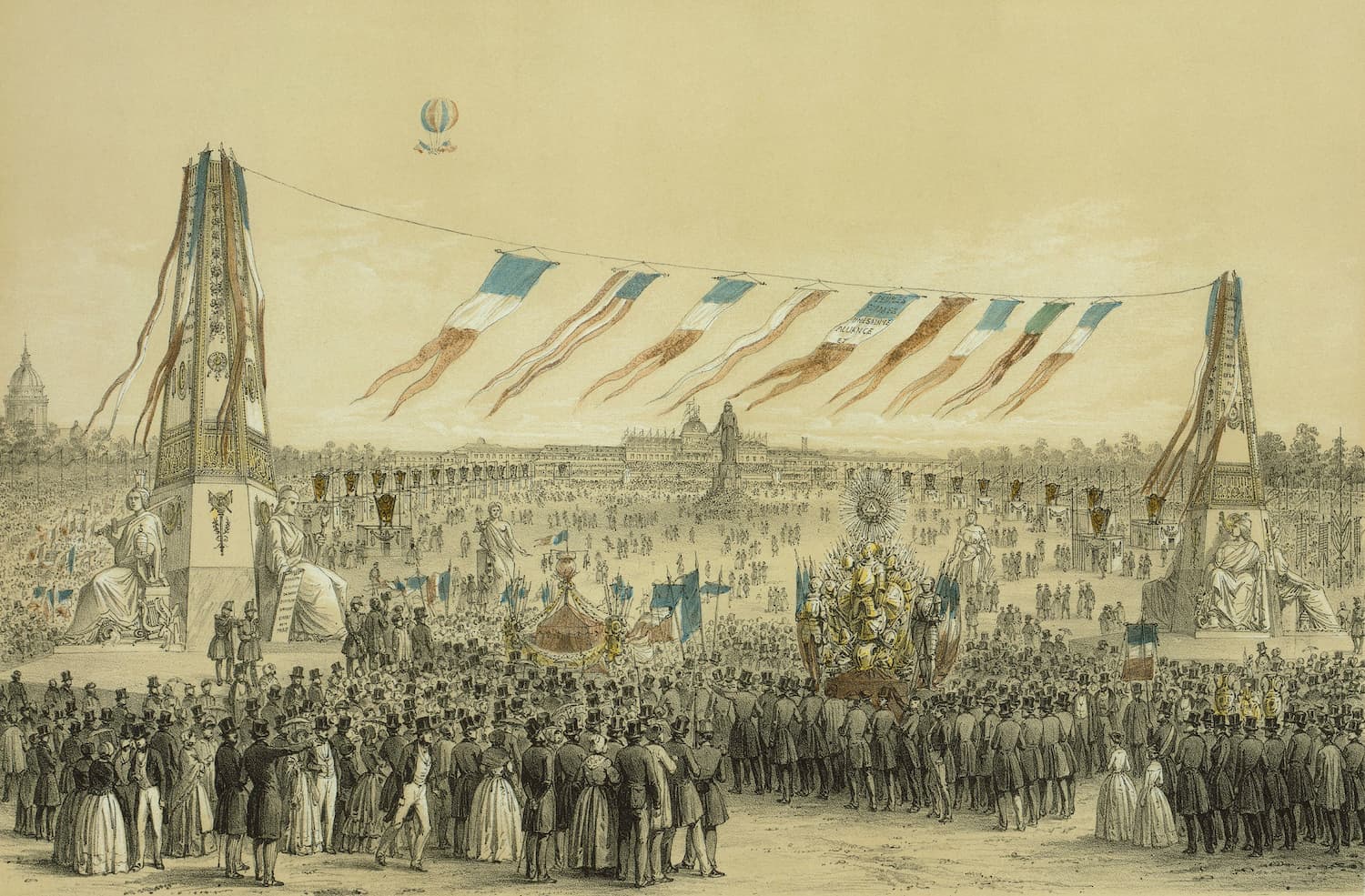

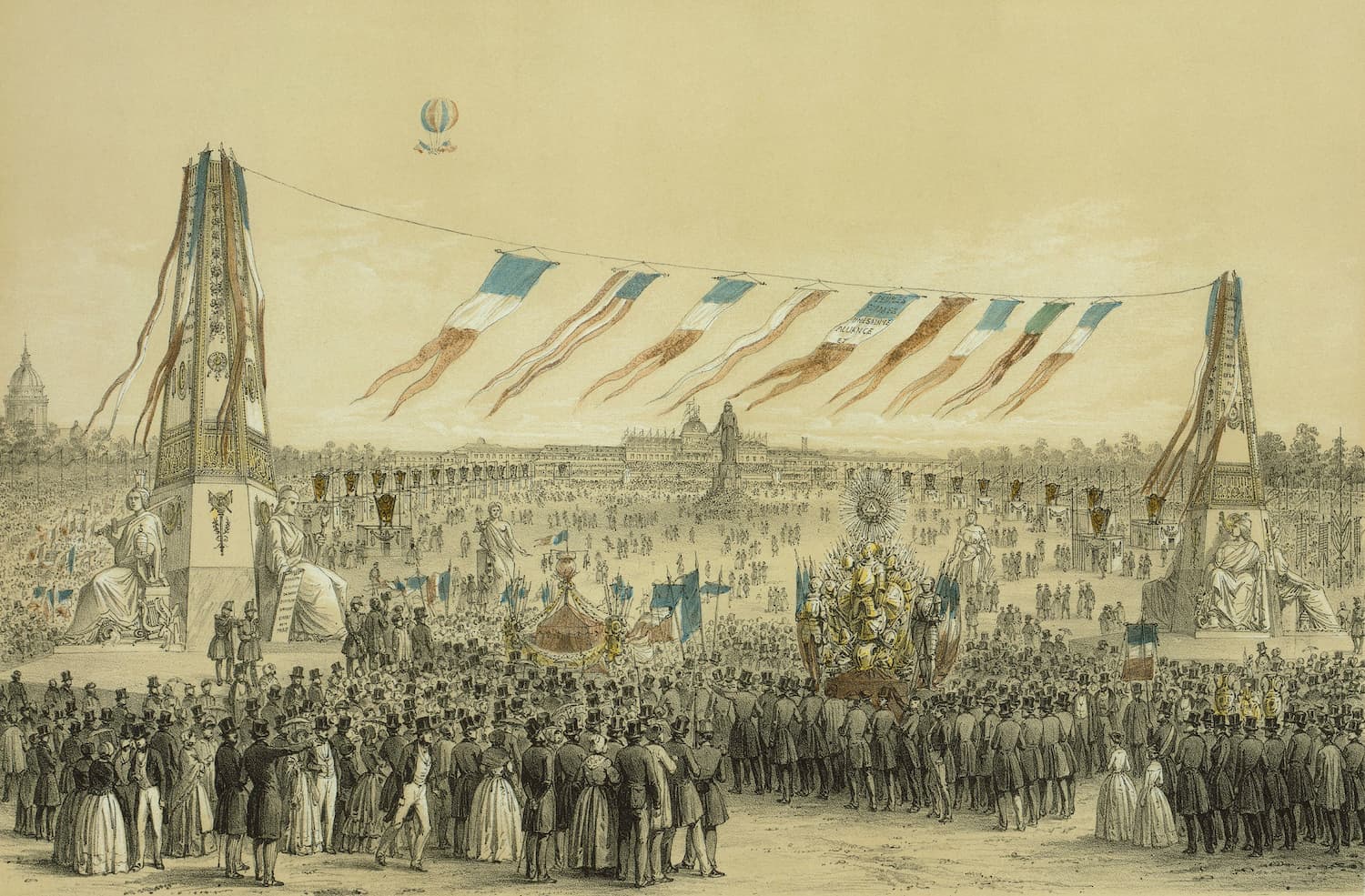

French Second Republic: Birth, Challenges, and Evolution

The French Second Republic was established in the aftermath of the February Revolution of 1848, which resulted in the overthrow of the July Monarchy.

The French Second Republic was established in the aftermath of the February Revolution of 1848, which resulted in the overthrow of the July Monarchy.