In the early 16th century, a German religious figure named Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church, initiating the Reformation. Swiftly, the Protestant revolutionary movement spread across Europe. In France, the Reformation was propagated by Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples before being significantly influenced by the ideas of Calvin. However, as the movement gained momentum, the reformists soon became the target of persecution.

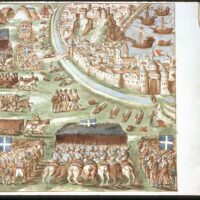

Divided, France descended into a series of civil wars continually fueled by the country’s political context—these are known as the Wars of Religion. Born in a conducive atmosphere, the armed conflicts persisted for over 30 years, concluding only with the reunification efforts of Henry IV. Consequently, the eight Wars of Religion inexorably paved the way for French absolutism.

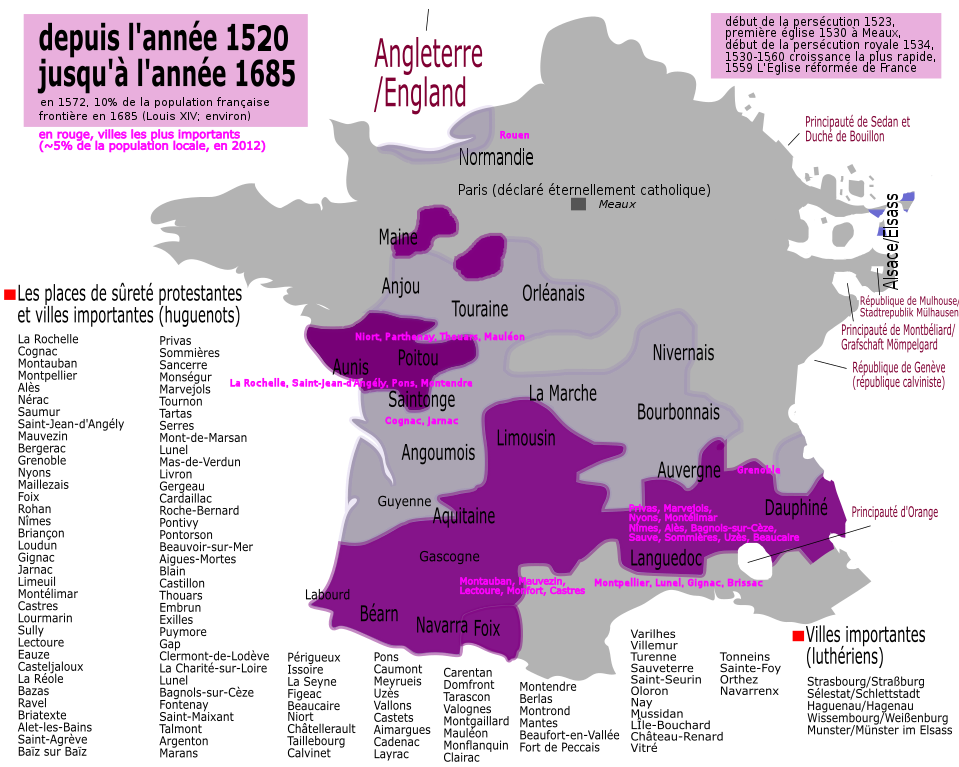

—>The Huguenots were French Calvinist Protestants who played a significant role in the French Wars of Religion. They were followers of the Reformed tradition and often faced persecution from the Catholic majority.

What Were the Origins of the French Wars of Religion?

During the reign of Francis I in France, the Protestant Reformation initially faced little opposition. Despite being a Catholic, the king demonstrated tolerance towards Protestants. However, their determined efforts to spread their faith eventually exasperated him. In 1534, for instance, hostile placards against the Mass were posted throughout the country, even in the royal chamber. This proved too much for the offended king, who immediately initiated a series of persecutions to expel the “heretics” from the country.

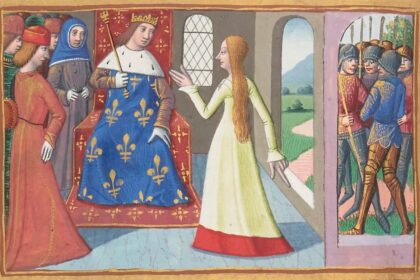

The repression continued under King Henry II, a less resolute Catholic who allowed the power of the Guise family, fervent Catholics hungry for power, to flourish during his reign. His death presented an opportunity for Protestants, as his inexperienced young son, Francis II, succeeded him. Exploiting the political vulnerability of the country, they organized the Amboise conspiracy in 1560 to influence the young monarch, but their plan failed.

Upon the king’s death, his brother, Charles IX, ascended to the throne at not even 10 years old. His mother, Catherine de’ Medici, assumed the regency. Despite her late husband’s behavior and the Amboise conspiracy, she aimed for reconciliation between the two religious factions. With the assistance of her new chancellor, Michel de l’Hôpital, she persuaded her son to sign the January Edict, which was relatively favorable to Protestants. However, Francis, Duke of Guise, was ousted from power due to his rigid pro-Catholic stance, disagreed, and organized the Massacre of Vassy in 1562. This tragic event immediately triggered the first of the eight French Wars of Religion.

How Were the Eight Wars of Religion Fought?

The First War of Religion, 1562-1563: The royal power’s policy of tolerance ended in failure, leading to the First War of Religion. The royal family appeared to be unable to control the situation. This war, which started with the Massacre of Vassy, sees Francis, Duke of Guise, and the Constable of Montmorency on the Catholic side, opposing the Prince of Condé and Gaspard II de Coligny on the Protestant side. It concludes with the assassination of Francis, Duke of Guise, and the Edict of Amboise. Despite a defeat at Dreux, the Protestants emerged from the conflict with significant advantages.

The Second War of Religion, 1567-1568: However, after only four years, the Second War of Religion erupted when the Prince of Condé attempted to kidnap the young King Charles IX. It ended with the Peace of Longjumeau in 1568, but it took only a year for both parties to resume hostilities.

The Third War of Religion, 1568-1570: Catherine de’ Medici’s decision to arrest the Prince of Condé led to the battles of Jarnac in 1569 and Moncontour. Both ended in defeat for the Protestants against the troops of the Duke of Anjou, the king’s brother and future Henry III. Yet, once again, a peace treaty signed at Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1570) grants them new privileges.

The Fourth War of Religion, 1572-1573: After the Third War of Religion, France was about to witness one of the worst massacres on its territory. Gaspard de Coligny, increasingly influential with the king, plans to take up arms to support William of Orange against the Spanish king’s forces. This displeases both Catherine de’ Medici and the Guise family, who take action: on August 22, 1572, Coligny narrowly escapes an assassination attempt. The wheels of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre were set in motion.

What Happened During the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre?

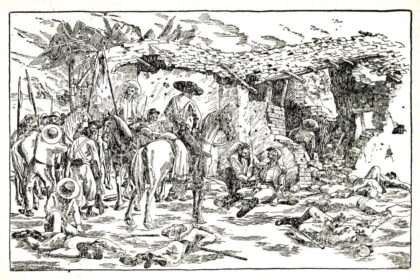

—>The Queen Mother convinces her son that the Protestants, gathered in the capital for the marriage of Margaret of Valois and Henry of Navarre, are conspiring against him. She also fears that the Guise may turn against royal authority, hence her preference to align with them. In panic, the king approves the execution of Protestant leaders. The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre resulted in 3,000 deaths in the capital on August 24, 1572. The Prince of Condé and Henry of Navarre, future Henry IV, are compelled to convert and are held at the court. This dramatic fourth war concluded with the Edict of Boulogne in July 1573. From that moment on, Protestants lost all trust in the monarchy and organized themselves. They raise an army and impose taxes on their territory.

The Fifth War of Religion, 1574-1576: Despite various treaties, the situation remains stagnant, inevitably leading to another conflict. This time, the Fifth War of Religion takes place in the first year of Henry III’s reign. It is triggered by the rebellion of his brother, the Duke of Alençon, who is joined by Henry of Navarre, having successfully escaped the Court. Notably, Henry of Navarre promptly renounced the Catholic faith. With him, the Protestants now have a capable leader to guide them to victory. The conflict concludes with the Peace of Monsieur, also known as the Edict of Beaulieu, which proves particularly favorable to the Protestants.

The Sixth War of Religion in 1577: These new favors granted to the Protestants were too much in the eyes of the Guise, who established the League, a military and political organization ready to ardently fight against the Reformists. Faced with the power of the Guise, Henry III had no choice but to align himself with the League. The sixth war concluded in a few months with the Treaty of Bergerac. This treaty deprived the Protestants of most of the advantages they had gained with the Edict of Beaulieu the previous year.

The Seventh War of Religion (1585-1588): In an attempt to appease tensions, the French king concedes fifteen secure locations to the Protestants for six months in the Treaty of Nerac (1579). However, after six months, conflict resumes as the Huguenots refuse to relinquish control of these locations. The Peace of Fleix in 1580 concluded the hostilities, granting the Protestants control of the fifteen secure locations for six years.

The Eighth War of Religion (1585-1588): In 1584, France teeters on the brink of a significant religious conflict. The king’s brother dies, leaving Henry III without an heir. Succumbing to pressure from the Catholic League, Henry III banned Protestant worship in 1585, sparking a war between Catholics and Henry of Navarre, the presumptive heir to the French crown. In a turn of events in May 1588, Parisian citizens revolted under the leadership of Henry I, Duke of Guise, forcing the king to abandon the capital and align with Henry of Navarre. Together, they attempt to reclaim Paris, but the king is assassinated shortly after choosing his ally as his successor.

Henry of Navarre, the future Henry IV, faced rejection from the Catholics, who continued to receive military support from Philip II of Spain. France descends into a significant political disorder. While Henry IV sought to secure the crown, some nobles exploited the situation, striving to establish autonomous territories, as seen with the dukes of Mercoeur and Épernon. Others, like the dukes of Savoy and Lorraine, aim to expand their territorial boundaries.

How Did Henry IV Put an End to the Wars of Religion?

Henry IV’s sole means of ascending to the throne of France was renouncing Protestantism and converting to Catholicism. Subsequently, the king underwent coronation in Chartres and finally entered Paris. His imperative task was to reunify France under the crown and to preempt a Protestant uprising, he enacted the Edict of Nantes in 1598. This edict granted Protestants significant religious freedom and civil equality.

Nevertheless, the challenge persisted; neither faction was genuinely content. The weariness of the populace, however, played a pivotal role in the cessation of armed conflicts. Henry IV managed to restore a semblance of equilibrium, albeit a precarious one, as evidenced by his assassination by François Ravaillac in 1610.

—>Catherine de’ Medici was the queen consort of Henry II and mother of three French kings. She played a central role in the French Wars of Religion, often trying to balance power between the Catholic and Protestant factions.

How Many People Died in the Wars of Religion?

The Wars of Religion concluded in 1598 after over 30 years of nearly uninterrupted conflict. During this period, France experienced a demographic decline, with the population decreasing by one to two million inhabitants between 1560 and 1600. It is challenging to attribute all these deaths solely to the Catholic-Protestant conflict. The casualties resulted not only from wars but also from famines, the plague, and unfavorable weather events, all of which are significant factors not to be overlooked.

Historians, on the other hand, put the death toll for the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre alone, which spread across the whole of France in 1572, at around 30,000 (and 20,000).

How Did the Wars of Religion Lead to French Absolutism?

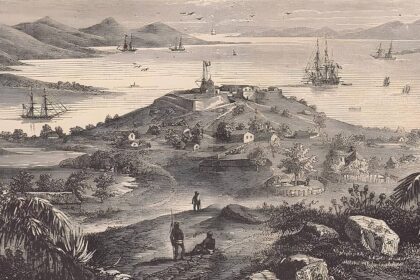

Despite the Edict of Nantes, religious conflicts did not vanish. During the reign of Louis XIII, Protestants revolted again, fearing renewed repression. However, under Richelieu’s policy, following the Siege of La Rochelle, the Peace of Alès was signed, stripping Protestants of all military and political power. Henry IV, Cardinal Richelieu, and Louis XIII paved the way for absolutism, fully established under Louis XIV. To reunify and consolidate France, the king believed in imposing a single religion on all, leading to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685.

Emerging in a context of monarchic fragility, the Wars of Religion often eluded royal authority, which alternated between conciliation and repression. The feudal powers, capable of destabilizing the kingdom at any moment, added to this fragility. Consequently, France descended into anarchy until Henry IV seized power. The king’s attempts at reconciliation and compromise ended in failure, as after his death, Protestant revolts and repression resurged. Tolerance was not yet embraced. Faced with this tumultuous past, the French kings opted for absolutism. Peaceful coexistence between the two Christian confessions would only materialize in the Enlightenment and the 19th century.

Chronology of the French Wars of Religion

- 1560: Protestant conspiracy at Amboise. Execution of conspirators.

First War (1562–1563)

- 1562: Massacre of Vassy (March); the “triumvirate” (Guise, Saint-André, Montmorency) seizes Rouen (October).

- 1563: Death of Francis, Duke of Guise, at the Siege of Orléans (February); Edict of Amboise (March).

Second War (1567–1568)

- 1568: Peace of Longjumeau (March).

Third War (1569–1571)

- 1569: Invasion of Béarn; victory of the Duke of Anjou and death of Condé at Jarnac (March); Francis, Duke of Anjou’s victory at Moncontour (October).

- 1570: Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye granting freedom of conscience and four strongholds to the Protestants (August).

- 1572: St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre (August 24).

Fourth War

- Failure of the Duke of Anjou before La Rochelle (February–June); Treaty of La Rochelle, giving the city, Nîmes, and Montauban to the Protestants (July).

Fifth War (1574–1576)

- 1575: Victory of the Henry I, Duke of Guise, (Scarface) at Dormans (October).

- 1576: Edict of Beaulieu (May) granting freedom of worship to Protestants everywhere except in Paris and eight safe places; birth of the League (June).

Sixth War

- Uprising of Henry of Navarre: the Duke of Anjou seizes La Charité (May); Peace of Bergerac (September), restricting the Edict of Beaulieu.

Seventh War (1579–1581)

- 1579 Peace of Nerac, giving fifteen strongholds to Protestants (February).

- 1584: Alliance of Guise and Philip II of Spain (Treaty of Joinville).

- 1585: Henry III allies with the League (July). Henry of Navarre, heir to the throne, is deprived of his rights (September).

Eighth War (1585–1588)

- 1587: Victory of Henry of Navarre at Coutras (October).

- 1588: Day of the Barricades in Paris and Henry III’s escape to Chartres (May); Estates General in Blois (October); assassination of the Duke of Guise in Blois (December).

- 1589: Alliance of Henry III and Henry of Navarre (Plessis-lez-Tours, April); siege of Paris by the two Henrys (July); assassination of Henry III (August); victory of Henry IV at Arques (September).

- 1590: Victory of Henry IV at Ivry (March), but he cannot take Paris (May).

- 1593: Henry IV abjures Protestantism (July).

- 1594: Henry IV enters Paris.

- 1595: Victory of Henry IV over the Spanish at Fontaine-Française (June); submission of the Duke of Mayenne, a Catholic claimant to the throne of France.

- 1598: Edict of Nantes (April); Peace of Vervins with the Spanish (May).