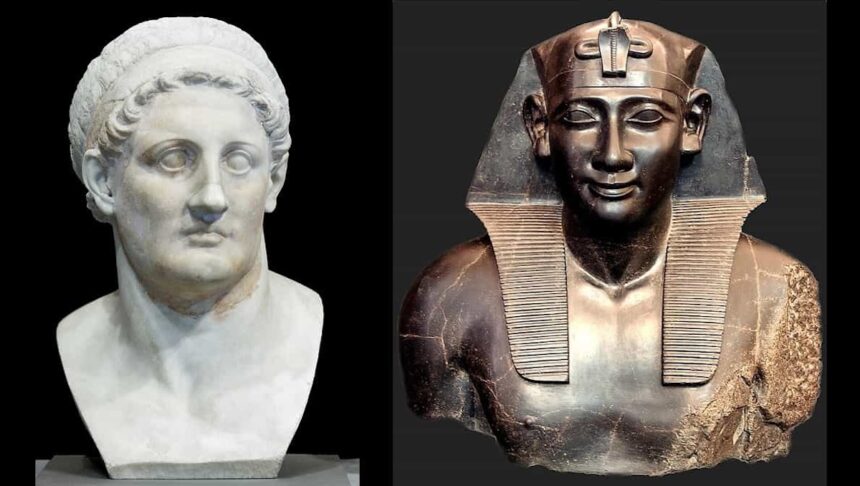

From Alexander the Great to Queen Cleopatra: How Egypt Became Greek

Upon the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, one of his generals, Ptolemy, gained control of Egypt. How did he and his "foreign" successors from the West manage to establish dominance over this Eastern territory, rich with twenty-five centuries of history?