Garden hermits, also known as ornamental hermits, were recluses who inhabited English landscape parks during the 18th and 19th centuries and entered into employment relationships. Garden hermits lived for a contractually defined period in specially designed hermitages and were required to appear at certain times of the day to entertain the owners of the parks and their guests with their presence.

The life of a Garden hermit

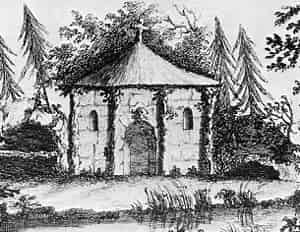

The requirements for the life of a garden hermit are known from newspaper advertisements. The most famous example of the employment of a garden hermit is found at Painshill Park, an estate of the nobleman Charles Hamilton (1704–1786), which was transformed into a landscape garden at great expense, featuring a typical grotto, neo-Gothic and Chinese architecture, winding paths, and a treehouse as a hermitage. Hamilton allegedly placed an advertisement stating that £700 would be earned by anyone willing to “stay seven years in the hermitage, where he should be provided with a Bible, spectacles, a foot mat, a straw mattress for a pillow, an hourglass as a timepiece, water for drinking, and food from the house. He must wear a woolen garment and under no circumstances cut his hair, beard, or nails, roam beyond the boundaries of Mr. Hamilton’s property, or even exchange a word with the servant.”

The long duration of the contract and the peculiar conditions of personal hygiene were not isolated cases. The lifestyle of a garden hermit was likely influenced by earth houses, which were common in rural areas until the early 20th century and were only banned in Britain by law in 1915.

Thus, a landowner near Preston advertised the position of a garden hermit for someone “willing to live underground for seven years without ever seeing a human being and without cutting his hair, beard, fingernails, or toenails.” However, recent studies have shown that this advertisement with the alleged working conditions was a construction of the media without concrete source evidence, which spread as a sensationalist trope through literature and over time solidified into a kind of purported “truth” through continued citation.

Obviously, interested parties were not only sought after, but also offered themselves. In an advertisement from 1810, a young man (garden hermits generally had to be of advanced age) stated that he wanted to “withdraw from the world and live as a hermit in any place in England” and was willing to “connect with a nobleman or gentleman who desires to have such a hermit.” In Hawkstone Park, a landscape garden visited by more than ten thousand visitors in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a mechanical doll, equipped with an hourglass, skull, and glasses on a table, took the place of the garden hermit. This doll was located in a hermitage and was operated by an employee who spoke to its mouth movements.

Cultural and Historical Aspects

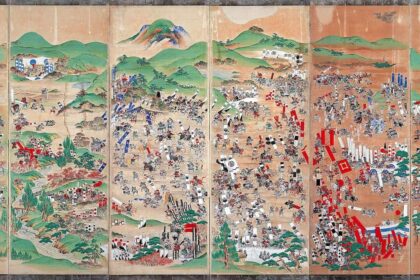

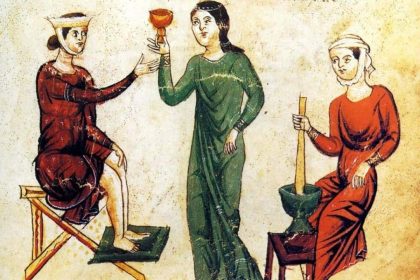

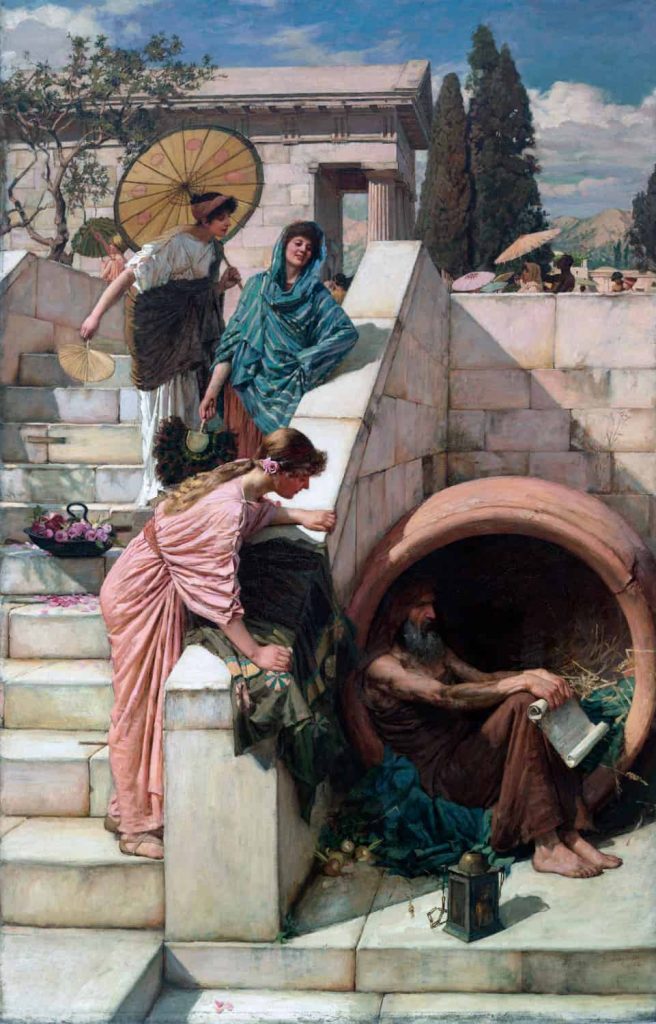

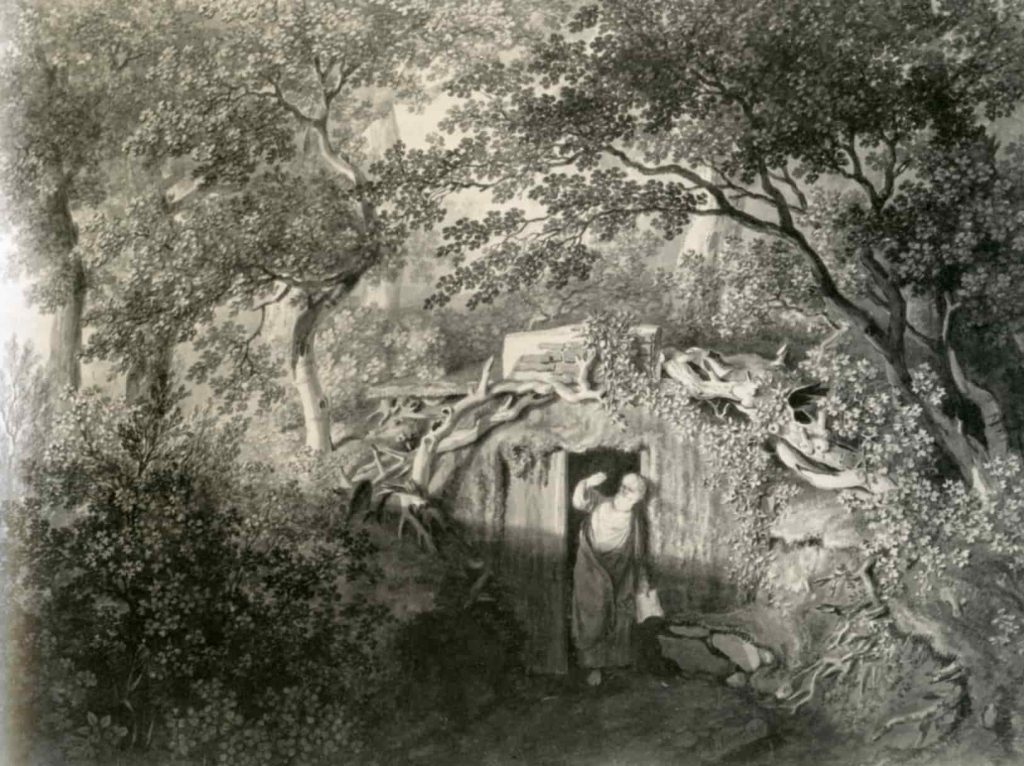

During the 18th century, the English landscape garden, as a walkable landscape painting, replaced the geometrically ordered Baroque garden. This development was related to the ongoing discussion in Europe since the 17th century about the natural state of humanity as opposed to civilization and communal living. The interest in garden hermits in this context corresponded to the interest in the “noble savage,” who embodied the unspoiled nature untouched by the constraints of communal life. In general, the elements of various traditions of rejecting civilization and their fascination with society were combined in garden hermits. The furnishing of the hermitage with a Bible referred to Christian hermitry, and the glasses referred to the scholar. Behind this was a long tradition that began with the traditions about the Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope (who was said to have lived in a tub as a despiser of civilization) and extended to Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver (in the third voyage to Laputa, where completely forgetful and dirty scientists appear).

The phenomenon of garden hermits in the 18th century accompanied an increased interest in English literature among hermits. A significant source of inspiration for this is considered to be the work of John Milton, especially his highly influential poem Il Penseroso (The Thoughtful), in which a forest wanderer spends his days in solitary studies and speaks the concluding words:

“And may at last my weary age

Find out the peaceful hermitage,

The hairy gown and mossy cell

Where I may sit and rightly spell

Of every star that heav’n doth show,

And every herb that sips the dew;

Till old experience do attain

To something like prophetic strain.

These pleasures, Melancholy, give,

And I with thee will choose to live.”

In numerous hermitages, which were already designed for Baroque gardens as places of secular contemplation, the closing lines from Milton’s poem appeared, and the arcadian motif of transience through the use of bones and skulls as memento mori also frequently appeared. The furnishing of the garden hermits with an hourglass (apart from its usefulness in adhering to the schedule for regular appearances in the field) also referred to this aspect of his performance task. The image of the garden hermit, which raised fundamental questions about the individual’s attitude towards society and life by abandoning typical civilized features such as refined clothing and personal hygiene, oscillated between seriousness and humor. This ambivalence was also often expressed in the follies (i.e., “architectural follies”) of the landscape gardens, which were widespread in 18th-century England, like the garden hermits.

The employment of garden hermits ceased in the first half of the 19th century, and the colonial expansion of European nation-states subsequently shifted the focus of interest. Ethnographic exhibitions took on the task of depicting images of people far from their own civilization. However, the term garden hermit remained present in the English-speaking world until today and no longer needs to be understood in its original sense but can generally stand for an eccentric way of life. Recent times have also shown increased artistic treatment of the topic in various media (literature, film, photo, and performance).

History

The trend of ornamental hermits spread between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries among the English aristocracy, when some nobles began to “decorate” their residences with hermits living in rudimentary dwellings. The task of the ornamental hermit was to appear at certain times of the day to be observed by his master and guests, and although he could not speak to anyone, on some occasions, he was required to engage the interlocutor in philosophical discourse. Ornamental hermits are mentioned in many sources for their eccentricity and are considered precursors to garden gnomes.

Professor Gordon Campbell of the University of Leicester reported in his book “The Hermit in the Garden” (2013) several precedents of ornamental hermits. Among them was the religious figure Francesco da Paola, who reportedly lived as a hermit in a cave on his father’s property in the early fifteenth century, later becoming the confidant and advisor to King Charles VIII of France.

In the following century, many estates of dukes and other lords in France included small chapels or other buildings where a religious hermit resided. According to Campbell, the first estate with a famous hermit (which included a small house, a chapel, and a garden) was the castle of Gaillon, renovated by Charles de Bourbon-Vendôme. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Louis XIV built a garden for a person named Marly a few miles north of Versailles, who initially served as his hermit. However, true garden hermits only became widespread in England in the late eighteenth century.

With the spread of Romanticism and the interest in mysticism among the English intellectual elite, hundreds of nobles hired decorative hermits, housing them in small dwellings built in the parks and gardens of their estates. Among the many accounts of the time, the Weld family employed an ornamental hermit who lived on the Lulworth estate in Dorset, while others were found in Painshill Park and Hawkstone Park. Charles Hamilton also hired a hermit for his residence. In a letter written by Hamilton, it is reported:

“… he will be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a stake for his pillow, an hourglass for timekeeping, water for his drink, and food from the house. He must wear a camel-colored tunic and never, under any circumstances, cut his hair, beard, or nails, wander beyond the limits of Mr. Hamilton’s property, or exchange a single word with the servant.”

However, his hermit was dismissed only three weeks after starting his assignment, as he disappeared from the estate and was found in a local pub. During the mid-nineteenth century, the spread in England of garden gnomes imported from Germany gradually ended the trend.

Characteristics

Ornamental hermits led a secluded and silent existence, living in small and rudimentary dwellings such as caves, huts, follies, or rocky gardens decorated with scenic objects. They were not allowed to shave their hair and beard, trim their nails, and were usually disinclined to wash. They dressed like druids, wearing tunics, and like real hermits, they had very few items to live with.

According to Edith Sitwell in her book “English Eccentrics” (1933), they could never leave the estate and converse with guests, and only appeared at certain times of the day when they could be observed by their masters and guests. Their employment contract lasted seven years, during which they were compensated with one meal a day.

Usually, if the hermit resigned from the position before his term ended, he would be deprived of payment for his services.

Garden hermits were sometimes assigned other tasks: in particular circumstances, they participated in noble dinners to entertain guests, served as waiters during parties, performed agricultural work, and engaged in philosophical discussions with guests.

Literature

Nonfiction

- Gordon Campbell: The Hermit in the Garden. From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-969699-4.

- Isabel Colegate: A Pelican in the Wilderness. Hermits, Solitaries, and Recluses. Harper-Collins, London 2002, ISBN 0-00-257142-0.

- Edith Sitwell: English Eccentrics.buy keflex online https://childrens-dentistry.com/scss/bootstrap/mixins/scss/keflex.html no prescription pharmacy

A gallery of most curious and remarkable ladies and gentlemen. (“English eccentrics”). Reprint. Wagenbach, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8031-1192-7, pp. 38–43.

Fiction

- Dieter Bachmann: The shorter breath. Novel. Residenz-Verlag, Salzburg 1998, ISBN 3-7017-1113-5.

- Matthew Francis: The Ornamental Hermit (Memento of 14 May 2008 at the Internet Archive) (winner of first prize in the 2000 Times Literary Supplement and Blackwell’s bookstore poetry competition)