The first surgeries ever made were painful and sometimes fatal, but new practices on both sides of the Atlantic reduced the fear of “going under the knife” as well as infection-related deaths. Robert Liston served as a senior surgeon at University College Hospital in London and performed the first ether surgery in Europe that was open to a crowd of doctors. During the operation where a patient’s arm would be cut under anesthesia with ether, Liston said: “We are going to try a Yankee dodge today, gentlemen, for making men insensible.”

Discovery of anesthesia

The Yankee maneuver he mentioned was performed for the first time two months ago, on October 16, 1846, at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. As the head surgeon and founder of the hospital, John Collins Warren had successfully removed a tumor from the chin of the 20-year-old printer, Gilbert Abbot. One month ago, Dr. William Thomas Green Morton became the first dentist to pull a patient’s tooth painlessly by anesthetizing with ether.

Once Abbot fainted, Warren cut off the tumor, and the patient soon recovered. “Have you felt pain?” Morton asked. “No, sir,” the young man replied, “But only the sensation-like scraping with a hoe or blunt instrument.”

Until then, surgeons had previously cut the arms or legs in surgeries without using anesthesia. The patient was often blindfolded and fixed to the stretcher, and a piece of skin was put between the teeth while the patient was still completely conscious and screaming in pain. More kind surgeons tried to hypnotize or magnetize the patient, make them almost pass out from lack of air, poison them, make them sleepy with opium, or freeze the part of the body that was going to be operated on.

A man lying on the operating table in one of our surgical hospitals is exposed to more chances of death than the English soldier on the field of Waterloo.

Sir James Young Simpson, obstetrician

The laughing gas

Dr. Morton was partnered with another dentist named Horace Wells, who was living in Boston for the first time and had used nitrogen protoxide, i.e. laughing gas, for anesthesia in dental surgery. In 1844, Wells pulled one of his own teeth while under the influence of nitrogen oxide and then successfully used this method on his patients. But Morton preferred to use ether to prevent pain. After developing a version that was successfully used as a surgical anesthetic in a hospital, Morton patented his discovery, called “Letheon.”

Before joining Warren’s surgery as an anesthesiologist, Dr. Morton was partnered with another dentist named Horace Wells, who lived in Boston and used nitrogen protoxide, i.e. laughing gas, for anesthesia for the first time in dental surgery. In 1844, Wells pulled out one of his own teeth while under the influence of nitrogen oxide, and then successfully used this method on his patients. But Morton preferred to use ether to prevent pain. After successfully demonstrating this surgical anesthesia method in a hospital, Morton patented his discovery, which he called “Letheon.”

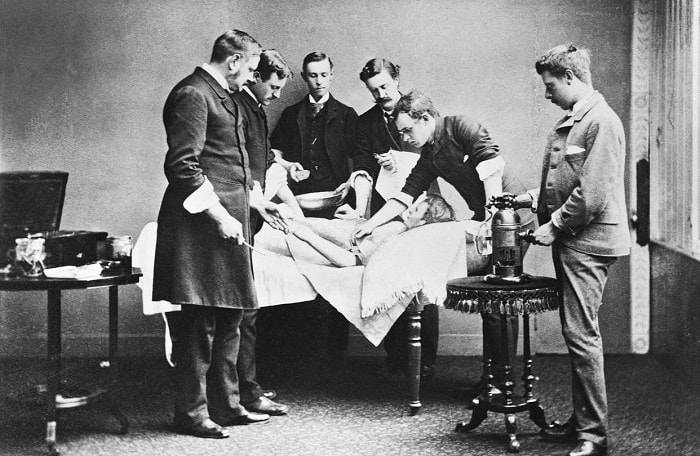

Meanwhile, Wells was campaigning that the nitrogen oxide he was using and claiming to be “safer” than ether was “first” in surgery. On the other hand, Scottish-born Robert Liston, Dr. He was prepared to follow Warren’s example and operated on a patient under anesthesia on December 21, 1846. Liston entered the hospital’s operating room with his usual coat and gown, which had not been cleaned for months. A little later, a patient named Frederick Churchill was brought. There was a disease in the femur that required cutting.

Wells launched a campaign about nitrogen oxide, which he claims to be “safer” than ether, and he used nitrogen oxide for the first time in surgery. On the other hand, Scottish Dr. Robert Liston chose to follow Warren’s method and operated on a patient under anesthesia on December 21, 1846. Liston entered the hospital’s operating room with his usual coat and gown, which had not been cleaned for months. A little later, a patient named Frederick Churchill was brought in. There was a disease in the femur that required cutting.

One of Liston’s colleagues anesthetized a patient with the aid of an inhaler device that has an ether-soaked sponge in it. Liston grabbed a long, surgical saw blade and quickly cut the thigh. He completed the amputation in about 30 seconds, and Churchill felt nothing. Liston then said, “This Yankee dodge, gentleman, beats mesmerism hollow.”

Hospital infection

Among those who witnessed that day was 19-year-old Joseph Lister, who attended Liston’s anatomy classes at University College. The unhygienic operating room conditions terrified Lister, as they put patients at risk of infection. At the time, one of every three patients was dying after an amputation surgery that is performed successfully in the hospitals of England. In almost all cases, deaths occurred as a result of inflammation of the wounds, and this was commonly referred to as “hospital gangrene.”

Most of the doctors thought that the infection in the surgical wounds was due to the air filling the room. But Lister thought that the deaths in the filthy wards filled to the brim were caused by the germs contained in them, not the air itself. It would take 20 years for Lister to prove this idea. In 1861, he was appointed to the Glasgow Royal Hospital as a surgeon. This appointment would result in a significant development in the discovery of anesthesia.

In the next five years, he found that half of the patients in the ward died due to septicemia or blood poisoning caused by inflamed wounds. In 1865, Lister examined the work of the French chemist Louis Pasteur, who argued that the diseases were spread by airborne microbes. Thus, Lister began experimenting with antiseptics, which he hoped would create a barrier between microbes and wounds. After trying many chemicals, he settled on carbolic acid, which was used to clean sewage.

Lister decided to try this carbolic acid in patients with compound fractures where the broken bone pierces the skin and often causes death due to infection. His first patient, 11-year-old James Greenlees, was admitted to the hospital on August 12, 1865, with a broken leg. Lister dressed the wound on James Greenlees with carbolic acid. The leg was then splinted and bandaged, and after four days, when the dressing was opened, there were no signs of inflammation or smell. In the following days, two more antiseptic dressings were applied and the wound began to heal. Only 6 weeks after the accident, James Greenlees’ leg healed, and the boy left the hospital on foot.