A former Allied supreme commander of NATO, U.S. General Wesley Clark famously observed, “Every army practices deception. If they don’t, they can’t win, and they know it.” Clark was fair, as wartime histories show. In ancient times, Hannibal had his oxen trot up a mountain pass with torches while he and his troops followed a separate path. Or consider Caesar, who enjoyed shrinking the legions’ encampment to make it seem that his army was smaller than it really was. However, it wasn’t until World War II that an entire military force was formed for the exclusive purpose of throwing off the enemy’s plans.

A renowned journalist, Ralph Ingersoll, was the one who first had the idea (1900–1985). He was stationed with the United States Army in London at the end of 1943, when he saw firsthand the plans for keeping the date and location of the Allied landings in Normandy secret. The Wehrmacht was duped by a slew of tricks, including inflated boats and fabricated radio transmissions. However, Ingersoll envisioned something more ambitious. What if a distinct military force could not only make dummies, but also quickly pretend the presence of one or perhaps two divisions?

General Jake Devers, the highest-ranking commander in Europe for the United States Army, was persuaded by Ingersoll and his superior, Colonel Billy Harris. On Christmas Eve of 1943, Devers ultimately presented the idea to the president by telegraph. The plan wasn’t ignited until January 20, 1944, a few weeks later.

1,100 men successfully acted as though they were 30,000 strong

The 23rd Headquarters, Special Troops was a newly formed military force that was quickly shortened to “Ghost Army.” A total of 1100 soldiers were tasked with creating the illusion that their division included as many as 30,000 troops via the use of props and other devices.

There were four distinct branches within the special force. The 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion Special was the biggest with 296 personnel. It had been around since the early 1940s, was in charge of camouflage, and featured some of the most out-of-the-ordinary soldiers in the United States Army, including painters, architects, illustrators, sculptors, and also other creative people.

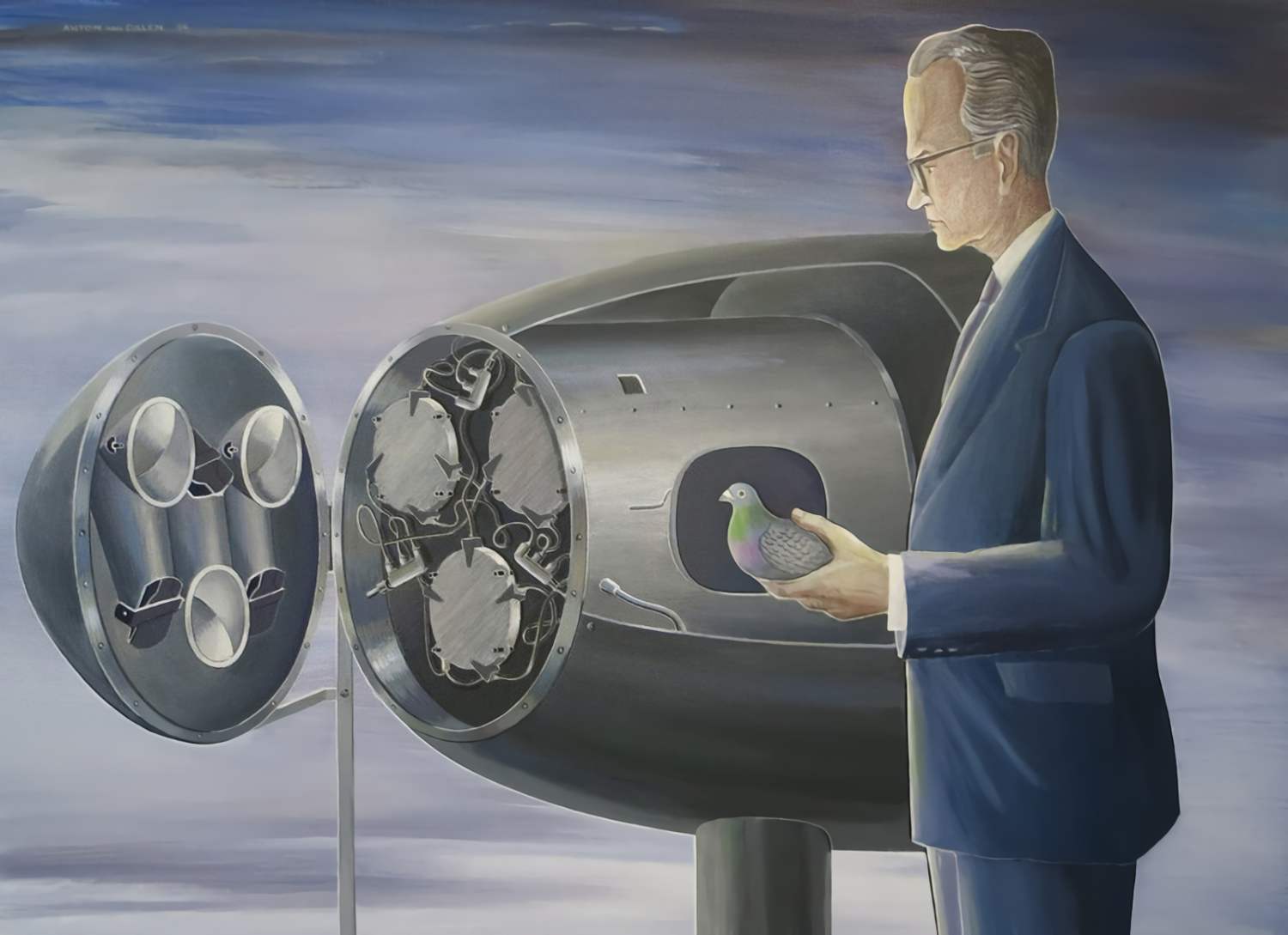

It comprised artist and painter Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015), American fashion designer Bill Blass (1922–2002), and landscape painter Arthur B. Singer (1917–1990), all of whom went on to prominence in their own industries. They were in charge of the showmanship of the wartime hoaxes. Tanks, artillery, jeeps, and even human troops were all part of their tremendous heritage of inflated dummies. Ingersoll eventually dubbed this group “my con artists” or “my tricksters.”

The 3132 Signal Service Company and the Signal Company Special were also members of the new military formation. The 145 men who made up the Signal Service were tasked with making the necessary white noise. They used cutting-edge recording technology and massive loudspeakers to recreate the noise of whole sections. The communications were handled by Signal Company Special. The radio signals were falsified. The men still had seasoned troops helping them guard and position the dummies.

First operations of the “Ghost Army” in Europe

In April of 1944, after three months of training, the regiment was sent to Europe. The American invasion of Normandy was a success on June 6, and the following day, the troops were sent on their first missions to the European continent. Many of them were taken aback, since they had only heard about the conflict via the media. They were being called out for missions more often, so they didn’t have much time to adjust.

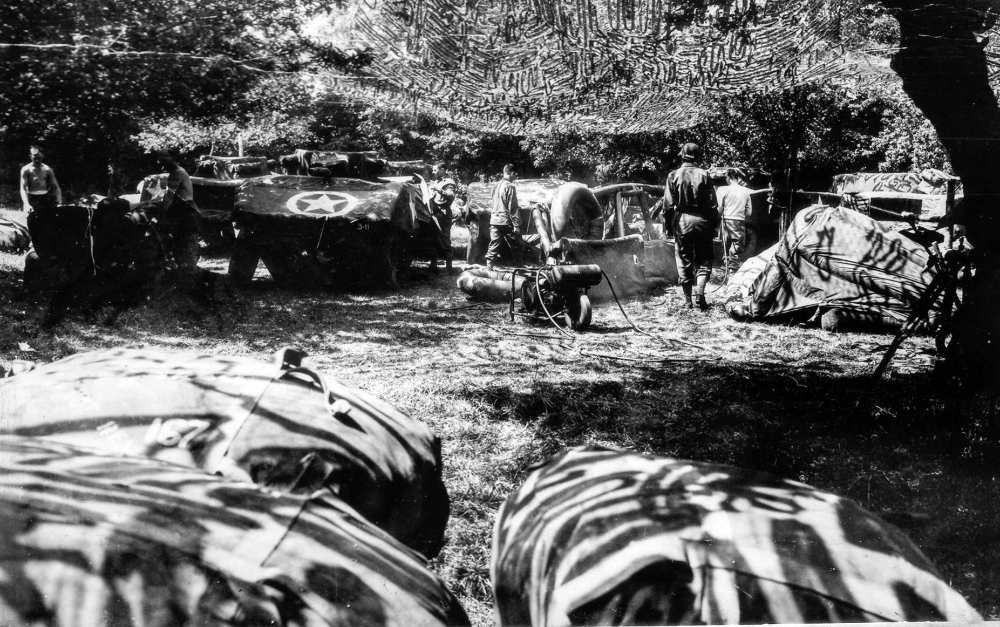

Therefore, on September 15, 1944, they helped General George S. Patton (1885–1954) and his 3rd Army capture the city of Metz. Patton ran into trouble because the Allies’ line was not continuous due to the tardiness of one division. There was a gap in defenses, and the “Ghost Army” was sent to fill it. Using their inflatable tanks for the first time, the experts acted out two brigades and a headquarters.

The noise division used massive loudspeakers to play recordings of tanks rolling across the region, while the radio section simulated transmissions to fool the Wehrmacht into thinking something was happening here. And to complete the image, bulldozers were employed to crush tank tracks into the ground, signs were painted, and badges were plastered onto vehicles.

The Wehrmacht did not strike because they mistook the Allied line for being continuous, hence, the strategy was successful. The missing division came to relieve the “Ghost Army” seven days later.

The climactic showdown on the Rhine

In the next six months, the “Ghost Army” launched a series of minor operations. There were fake cannons and command centers here and there. In March of 1945, the Allies planned their last major operation: Crossing the Rhine with the 21st Army Group, a massive organization commanded by the British.

The overall mission, codenamed “Plunder,” was broken down into smaller missions. The Ghost Army was in charge of one of these. It was a joint effort by the 9th United States Army and the crossing’s organizers to keep the crossing’s actual time a secret. The plan was to make it seem as if the Allies couldn’t make it over the Rhine until at least April 1.

Part two of the endeavor, dubbed “Viersen,” included covering up the actual crossing’s location. Efforts of every kind were made. In order to conceal the movements of their troops, camouflage specialists at Krefeld on the Rhine fired smoke grenades. The next step was to establish bogus supply depots, command posts, anti-aircraft installations, and airstrips.

The force stationed around 200 inflatable vehicles in backyards, forests, and along highways in the area of Anrath and Dülken. The sound department was also running at full steam; the sounds of moving tanks and vehicles could be heard from the speakers, and the sounds of a construction site were used to represent the building of improvised bridges.

Two U.S. Army divisions crossed the Rhine 20 kilometers to the north on March 24, and they encountered no opposition. It seems that the Wehrmacht did not anticipate the crossing at this time.

The reason “Ghost Army” remained mostly unknown until the 1990s

The “Ghost Army’s” last mission was also its last big operation. The personnel went back to the States not long after Germany capitulated. The initiation of their deployment in the Pacific region was planned but never materialized. The U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ultimately led to Japan’s unconditional surrender. The special force was demobilized and integrated into society not long after.

Only in the middle of the 1990s did the official history of the “Ghost Army” emerge. To have the option of activating the unit during the Cold War, the pertinent data had been kept under lock and key until that point.

The efficiency of the “Ghost Army” is still up for debate. Obviously, it is hard to evaluate the efficiency of a force whose mission was to remain unseen. This might be seen as a sign of its success since German archives indicate that some of the deceptions were taken. In the book “The Ghost Army of World War II,” U.S. Army Combined Arms Center’s Roy Eichhorn asks, “Did it baffle the Germans every time?” Probably not. Did it cause the Germans to react in the ways that we wanted them to react? Definitely.”

The “Ghost Army” left an indelible mark, at least in the works of its former members. Art critic Eugene C. Goossen (1920–1997) wrote about Ellsworth Kelly’s camouflage work for the United States military, stating, “The involvement with form and shadow, with the construction and destruction of the visible…was to affect nearly everything he did in painting and sculpture.”

Bibliography

- Ghost Army: The Combat Con Artists of World War II | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans (nationalww2museum.org)

- 12 on 12: Ghost Army | WPRI.com

- The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy – Rick Beyer, Elizabeth Sayles

- Kneece, Jack (2001). Ghost army of World War II. Gretna: Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1565548763.